- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Posterior Compartment

- •2.2 Anterior Compartment

- •2.3 Middle Compartment

- •2.4 Perineal Body

- •3 Compartments

- •3.1 Posterior Compartment

- •3.1.1 Connective Tissue Structures

- •3.1.2 Muscles

- •3.1.3 Reinterpreted Anatomy and Clinical Relevance

- •3.2 Anterior Compartment

- •3.2.1 Connective Tissue Structures

- •3.2.2 Muscles

- •3.2.3 Reinterpreted Anatomy and Clinical Relevance

- •3.2.4 Important Vessels, Nerves, and Lymphatics of the Anterior Compartment

- •3.3 Middle Compartment

- •3.3.1 Connective Tissue Structures

- •3.3.2 Muscles

- •3.3.3 Reinterpreted Anatomy and Clinical Relevance

- •3.3.4 Important Vessels, Nerves, and Lymphatics of the Middle Compartment

- •4 Perineal Body

- •References

- •MR and CT Techniques

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2.1 Spasmolytic Medication

- •2.3.2 Diffusion-Weighted Imaging

- •2.3.3 Dynamic Contrast Enhancement

- •3 CT Technique

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Technical Disadvantages

- •3.4 Oral and Rectal Contrast

- •References

- •Uterus: Normal Findings

- •1 Introduction

- •References

- •1 Clinical Background

- •1.1 Epidemiology

- •1.2 Clinical Presentation

- •1.3 Embryology

- •1.4 Pathology

- •2 Imaging

- •2.1 Technique

- •2.2.1 Class I Anomalies: Dysgenesis

- •2.2.2 Class II Anomalies: Unicornuate Uterus

- •2.2.3 Class III Anomalies: Uterus Didelphys

- •2.2.4 Class IV Anomalies: Bicornuate Uterus

- •2.2.5 Class V Anomalies: Septate Uterus

- •2.2.6 Class VI Anomalies: Arcuate Uterus

- •2.2.7 Class VII Anomalies

- •References

- •Benign Uterine Lesions

- •1 Background

- •1.1 Uterine Leiomyomas

- •1.1.1 Epidemiology

- •1.1.2 Pathogenesis

- •1.1.3 Histopathology

- •1.1.4 Clinical Presentation

- •1.1.5 Therapy

- •1.1.5.1 Indications

- •1.1.5.2 Medical Therapy and Ablation

- •1.1.5.3 Surgical Therapy

- •1.1.5.4 Uterine Artery Embolization (UAE)

- •1.1.5.5 Magnetic Resonance-Guided Focused Ultrasound

- •2 Adenomyosis of the Uterus

- •2.1 Epidemiology

- •2.2 Pathogenesis

- •2.3 Histopathology

- •2.4 Clinical Presentation

- •2.5 Therapy

- •3 Imaging

- •3.2 Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- •3.2.1 Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Technique

- •3.2.2 MR Appearance of Uterine Leiomyomas

- •3.2.3 Locations, Growth Patterns, and Imaging Characteristics

- •3.2.4 Histologic Subtypes and Forms of Degeneration

- •3.2.5 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.2.6 MR Appearance of Uterine Adenomyosis

- •3.2.7 Locations, Growth Patterns, and Imaging Characteristics

- •3.2.8 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.3 Computed Tomography

- •3.3.1 CT Technique

- •3.3.2 CT Appearance of Uterine Leiomyoma and Adenomyosis

- •3.3.3 Atypical Appearances on CT and Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1 Indications

- •4.2 Technique

- •Bibliography

- •Cervical Cancer

- •1 Background

- •1.1 Epidemiology

- •1.2 Pathogenesis

- •1.3 Screening

- •1.4 HPV Vaccination

- •1.5 Clinical Presentation

- •1.6 Histopathology

- •1.7 Staging

- •1.8 Growth Patterns

- •1.9 Treatment

- •1.9.1 Treatment of Microinvasive Cervical Cancer

- •1.9.2 Treatment of Grossly Invasive Cervical Carcinoma (FIGO IB-IVA)

- •1.9.3 Treatment of Recurrent Disease

- •1.9.4 Treatment of Cervical Cancer During Pregnancy

- •1.10 Prognosis

- •2 Imaging

- •2.1 Indications

- •2.1.1 Role of CT and MRI

- •2.2 Imaging Technique

- •2.2.2 Dynamic MRI

- •2.2.3 Coil Technique

- •2.2.4 Vaginal Opacification

- •2.3 Staging

- •2.3.1 General MR Appearance

- •2.3.2 Rare Histologic Types

- •2.3.3 Tumor Size

- •2.3.4 Local Staging

- •2.3.4.1 Stage IA

- •2.3.4.2 Stage IB

- •2.3.4.3 Stage IIA

- •2.3.4.4 Stage IIB

- •2.3.4.5 Stage IIIA

- •2.3.4.6 Stage IIIB

- •2.3.4.7 Stage IVA

- •2.3.4.8 Stage IVB

- •2.3.5 Lymph Node Staging

- •2.3.6 Distant Metastases

- •2.4 Specific Diagnostic Queries

- •2.4.1 Preoperative Imaging

- •2.4.2 Imaging Before Radiotherapy

- •2.5 Follow-Up

- •2.5.1 Findings After Surgery

- •2.5.2 Findings After Chemotherapy

- •2.5.3 Findings After Radiotherapy

- •2.5.4 Recurrent Cervical Cancer

- •2.6.1 Ultrasound

- •2.7.1 Metastasis

- •2.7.2 Malignant Melanoma

- •2.7.3 Lymphoma

- •2.8 Benign Lesions of the Cervix

- •2.8.1 Nabothian Cyst

- •2.8.2 Leiomyoma

- •2.8.3 Polyps

- •2.8.4 Rare Benign Tumors

- •2.8.5 Cervicitis

- •2.8.6 Endometriosis

- •2.8.7 Ectopic Cervical Pregnancy

- •References

- •Endometrial Cancer

- •1.1 Epidemiology

- •1.2 Pathology and Risk Factors

- •1.3 Symptoms and Diagnosis

- •2 Endometrial Cancer Staging

- •2.1 MR Protocol for Staging Endometrial Carcinoma

- •2.2.1 Stage I Disease

- •2.2.2 Stage II Disease

- •2.2.3 Stage III Disease

- •2.2.4 Stage IV Disease

- •4 Therapeutic Approaches

- •4.1 Surgery

- •4.2 Adjuvant Treatment

- •4.3 Fertility-Sparing Treatment

- •5.1 Treatment of Recurrence

- •6 Prognosis

- •References

- •Uterine Sarcomas

- •1 Epidemiology

- •2 Pathology

- •2.1 Smooth Muscle Tumours

- •2.2 Endometrial Stromal Tumours

- •3 Clinical Background

- •4 Staging

- •5 Imaging

- •5.1 Leiomyosarcoma

- •5.2.3 Undifferentiated Uterine Sarcoma

- •5.3 Adenosarcoma

- •6 Prognosis and Treatment

- •References

- •1.1 Anatomical Relationships

- •1.4 Pelvic Fluid

- •2 Developmental Anomalies

- •2.1 Congenital Abnormalities

- •2.2 Ovarian Maldescent

- •3 Ovarian Transposition

- •References

- •1 Introduction

- •4 Benign Adnexal Lesions

- •4.1.1 Physiological Ovarian Cysts: Follicular and Corpus Luteum Cysts

- •4.1.1.1 Imaging Findings in Physiological Ovarian Cysts

- •4.1.1.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1.2 Paraovarian Cysts

- •4.1.2.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.1.2.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1.3 Peritoneal Inclusion Cysts

- •4.1.3.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.1.3.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1.4 Theca Lutein Cysts

- •4.1.4.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.1.4.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1.5 Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

- •4.1.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.1.5.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.2.1 Cystadenoma

- •4.2.1.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.2.1.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.2.2 Cystadenofibroma

- •4.2.2.1 Imaging Features

- •4.2.3 Mature Teratoma

- •4.2.3.1 Mature Cystic Teratoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •4.2.3.2 Monodermal Teratoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •4.2.4 Benign Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors

- •4.2.4.1 Fibroma and Thecoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •4.2.4.2 Sclerosing Stromal Tumor

- •Imaging Findings

- •4.2.5 Brenner Tumors

- •4.2.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.2.5.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •5 Functioning Ovarian Tumors

- •References

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Context

- •2.2.2 Indications According to Simple Rules

- •References

- •CT and MRI in Ovarian Carcinoma

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Familial or Hereditary Ovarian Cancers

- •3 Screening for Ovarian Cancer

- •5 Tumor Markers

- •6 Clinical Presentation

- •7 Imaging of Ovarian Cancer

- •7.1.2 Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

- •7.1.3 Ascites

- •7.3 Staging of Ovarian Cancer

- •7.3.1 Staging by CT and MRI

- •Imaging Findings According to Tumor Stages

- •Value of Imaging

- •7.3.2 Prediction of Resectability

- •7.4 Tumor Types

- •7.4.1 Epithelial Ovarian Cancer

- •High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer

- •Low-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer

- •Mucinous Epithelial Ovarian Cancer

- •Endometrioid Ovarian Carcinomas

- •Clear Cell Carcinomas

- •Imaging Findings of Epithelial Ovarian Cancers

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Borderline Tumors

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Recurrent Ovarian Cancer

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Value of Imaging

- •Malignant Germ Cell Tumors

- •Dysgerminomas

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Immature Teratomas

- •Imaging Findings

- •Malignant Transformation in Benign Teratoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Sex-Cord Stromal Tumors

- •Granulosa Cell Tumors

- •Imaging Findings

- •Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumor

- •Imaging Findings

- •Ovarian Lymphoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •7.4.3 Ovarian Metastases

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •7.5 Fallopian Tube Cancer

- •7.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •References

- •Endometriosis

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Sonography

- •3 MR Imaging Findings

- •References

- •Vagina and Vulva

- •1 Introduction

- •3.1 CT Appearance

- •3.2 MRI Protocol

- •3.3 MRI Appearance

- •4.1 Imperforate Hymen

- •4.2 Congenital Vaginal Septa

- •4.3 Vaginal Agenesis

- •5.1 Vaginal Cysts

- •5.1.1 Gardner Duct Cyst (Mesonephric Cyst)

- •5.1.2 Bartholin Gland Cyst

- •5.2.1 Vaginal Infections

- •5.2.1.1 Vulvar Infections

- •5.2.1.2 Vulvar Thrombophlebitis

- •5.3 Vulvar Trauma

- •5.4 Vaginal Fistula

- •5.5 Post-Radiation Changes

- •5.6 Benign Tumors

- •6.1 Vaginal Malignancies

- •6.1.1 Primary Vaginal Carcinoma

- •6.1.1.1 MRI Findings

- •6.1.1.2 Lymph Node Drainage

- •6.1.1.3 Recurrence and Complications

- •6.1.2 Non-squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Vagina

- •6.1.2.1 Adenocarcinoma

- •6.1.2.2 Melanoma

- •6.1.2.3 Sarcomas

- •6.1.2.4 Lymphoma

- •6.2 Vulvar Malignancies

- •6.2.1 Vulvar Carcinoma

- •6.2.2 Melanoma

- •6.2.3 Lymphoma

- •6.2.4 Aggressive Angiomyxoma of the Vulva

- •7 Vaginal Cuff Disease

- •7.1 MRI Findings

- •8 Foreign Bodies

- •References

- •Imaging of Lymph Nodes

- •1 Background

- •3 Technique

- •3.1.1 Intravenous Unspecific Contrast Agents

- •3.1.2 Intravenous Tissue-Specific Contrast Agents

- •References

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.1.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.1.3 Value of Imaging

- •2.2 Pelvic Inflammatory

- •2.2.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.3 Hydropyosalpinx

- •2.3.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.3.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.4 Tubo-ovarian Abscess

- •2.4.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.4.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.4.3 Value of Imaging

- •2.5 Ovarian Torsion

- •2.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.5.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.5.3 Diagnostic Value

- •2.6 Ectopic Pregnancy

- •2.6.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.6.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.6.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.1 Pelvic Congestion Syndrome

- •3.1.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.1.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.1.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.2 Ovarian Vein Thrombosis

- •3.2.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.2.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.2.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.3 Appendicitis

- •3.3.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.3.2 Value of Imaging

- •3.4 Diverticulitis

- •3.4.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.4.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.4.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.5 Epiploic Appendagitis

- •3.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.5.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.5.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.6 Crohn’s Disease

- •3.6.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.6.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.6.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.7 Rectus Sheath Hematoma

- •3.7.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.7.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.7.3 Value of Imaging

- •References

- •MRI of the Pelvic Floor

- •1 Introduction

- •2 Imaging Techniques

- •3.1 Indications

- •3.2 Patient Preparation

- •3.3 Patient Instruction

- •3.4 Patient Positioning

- •3.5 Organ Opacification

- •3.6 Sequence Protocols

- •4 MR Image Analysis

- •4.1 Bony Pelvis

- •5 Typical Findings

- •5.1 Anterior Compartment

- •5.2 Middle Compartment

- •5.3 Posterior Compartment

- •5.4 Levator Ani Muscle

- •References

- •Evaluation of Infertility

- •1 Introduction

- •2 Imaging Techniques

- •2.1 Hysterosalpingography

- •2.1.1 Cycle Considerations

- •2.1.2 Technical Considerations

- •2.1.3 Side Effects and Complications

- •2.1.5 Pathological Findings

- •2.1.6 Limitations of HSG

- •2.2.1 Cycle Considerations

- •2.2.2 Technical Considerations

- •2.2.2.1 Normal and Abnormal Anatomy

- •2.2.3 Accuracy

- •2.2.4 Side Effects and Complications

- •2.2.5 Limitations of Sono-HSG

- •2.3 Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- •2.3.1 Indications

- •2.3.2 Technical Considerations

- •2.3.3 Limitations

- •3 Ovulatory Dysfunction

- •4 Pituitary Adenoma

- •5 Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

- •7 Uterine Disorders

- •7.1 Müllerian Duct Anomalies

- •7.1.1 Class I: Hypoplasia or Agenesis

- •7.1.2 Class II: Unicornuate

- •7.1.3 Class III: Didelphys

- •7.1.4 Class IV: Bicornuate

- •7.1.5 Class V: Septate

- •7.1.6 Class VI: Arcuate

- •7.1.7 Class VII: Diethylstilbestrol Related

- •7.2 Adenomyosis

- •7.3 Leiomyoma

- •7.4 Endometriosis

- •References

- •MR Pelvimetry

- •1 Clinical Background

- •1.3.1 Diagnosis

- •1.3.2.1 Cephalopelvic Disproportion

- •1.3.4 Inadequate Progression of Labor due to Inefficient Contraction (“the Powers”)

- •2.2 Palpation of the Pelvis

- •3 MR Pelvimetry

- •3.2 MR Imaging Protocol

- •3.3 Image Analysis

- •3.4 Reference Values for MR Pelvimetry

- •5 Indications for Pelvimetry

- •References

- •MR Imaging of the Placenta

- •2 Imaging of the Placenta

- •3 MRI Protocol

- •4 Normal Appearance

- •4.1 Placenta Variants

- •5 Placenta Adhesive Disorders

- •6 Placenta Abruption

- •7 Solid Placental Masses

- •9 Future Directions

- •References

- •Erratum to: Endometrial Cancer

430 |

G. Heinz-Peer |

|

|

2\ Imaging Techniques

2.1\ Hysterosalpingography

Hysterosalpingography (HSG) uses fluoroscopic control to introduce radiographic contrast material into the uterine cavity and fallopian tubes. While today HSG is used primarily to assess tubal patency, this technique also provides indirect evidence for uterine pathology through depiction of abnormal uterine cavity contours.

2.1.1\ Cycle Considerations

HSG should not be performed if there is a possibility of a normal intrauterine pregnancy. To avoid irradiating an early pregnancy, the “10-day rule” can be used. That means the procedure should not be performed if the interval of time from the start of the last menses is greater than 10–12 days. If the patient has cycles that are longer than 28 days (menses start usually 14 days after ovulation), the 10-day rule can be stretched to 13–15 days. If the patient has irregular cycles or absent menses, a pregnancy test before performing HSG is recommended.

2.1.2\ Technical Considerations

The patient is placed supine with her knees flexed and heels apart. Stirrups on the table to support the feet can be used. The cervix is exposed with a speculum. Visualization of the cervix may be helped by elevating the patient’s pelvis, particularly in thin women. The cervix and vagina are copiously swabbed with a cleansing solution such as Betadine and the HSG cannula is placed. A variety of cannulas can be used for HSG (Margolin 1988; Sholkoff 1987; Thurmond et al. 1990). Once correct placement of the cannula is confirmed, the speculum should be removed. Leaving the speculum in is uncomfortable for the patient and a metal speculum obscures findings. Using fluoroscopic guidance, contrast agent at room temperature is slowly injected, usually 5–10 mL over 1 min, and radiographs are obtained. Injection of contrast agent is halted when

adequate free spill into the peritoneal cavity is documented, when myometrial or venous intravasation occurs, or when the patient complains of increased cramping, which usually occurs when the tubes are blocked.

2.1.3\ Side Effects and Complications

Mild discomfort or pain is commonly experienced by women undergoing HSG (Soules and Spadoni 1982). Routine analgesia is not necessary, although oral Ibuprofen is a reasonable preprocedure medication. Reassurance and rapid and skillful completion of the examination are the best approach. Mild vaginal bleeding is common after HSG. Severe bleeding requiring curettage is unusual and is presumably related to underlying pathology such as endometrial polyps. Other side effects such as vasovagal reactions and hyperventilation may occur and their prevalence may be reduced if the examiner is experienced and calming.

Pelvic infection is a serious complication of HSG, causing tubal damage. In a private practice setting, the overall incidence of post-HSG pelvic infection was 1.4%, occurring predominantly in women with dilated tubes (Pittaway et al. 1983). For this reason, if dilated tubes are noted during the HSG procedure, particularly if there is a dilated tube with free spill, prophylactic administration of antibiotics (e.g., doxycy- cline—200 mg orally) should be performed before the patient leaves the department and a prescription for 5 days should be given to the patient.

An allergic or idiosyncratic reaction related to the contrast medium can occur after HSG, although the incidence is unknown and is presumably quite low.

Radiation exposure is a side effect not shared by sonohysterosalpingography (SSG). It is a concern, because the women being examined are of reproductive age. The incidence of irradiating an early pregnancy is quite low when HSG is routinely performed in the follicular phase of the cycle. Although cases are few, there is nothing to suggest that inadvertent performance of HSG in early pregnancy is harmful to the fetus (Justesen

Evaluation of Infertility |

431 |

|

|

et al. 1986). Radiation exposure to the ovaries is minimal and can be further reduced by using good fluoroscopic technique and obtaining only the number of radiographs necessary to make an accurate diagnosis.

2.1.4\ Anatomy and Physiology

of Fallopian Tubes

The fallopian tubes connect the peritoneal cavity to the “extraperitoneal space.” Their function and anatomy are complex, and include conduction of sperm from the uterine end toward the ampulla, conduction of ova in the other direction from the fimbriated end to the ampulla, and support as well as conduction of the early embryo from the

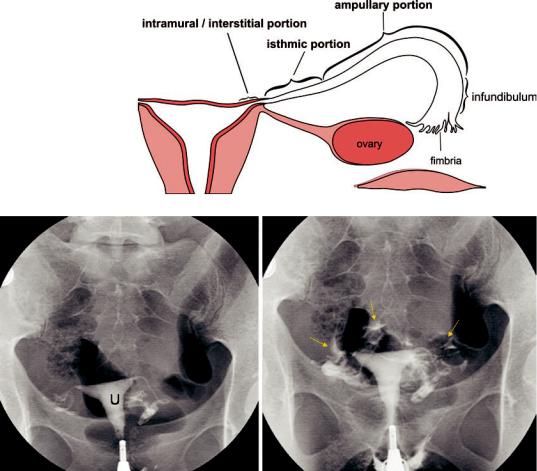

Fig. 1a Scheme of normal fallopian tubes: the normal fallopian tube ranges in length from 7 to 16 cm (average 12 cm). The tube is divided into four regions: (a) intramural or interstitial portion (1–2 cm), (b) isthmic portion,

(2–3 cm), (c) ampullary portion (5–8 cm), and (d) infundibulum terminating into the fimbria

ampulla into the uterus for implantation. The normal fallopian tube ranges in length from 7 to 16 cm, with an average length of 12 cm (Fig. 1a). The tube is divided into four regions: (a) the intramural or interstitial portion, which occurs in the wall of the uterine fundus and is 1–2 cm long;

(b) the isthmic portion, which is about 2–3 cm long; (c) the ampullary portion, which is 5–8 cm long; and (d) the infundibulum, which is the trumpet-shaped distal end of the tube terminating in the fimbria. Patency of the fallopian tubes is established when contrast medium flows through them and freely around the ovary and loops of bowel at the time of salpingography, using either fluoroscopic or sonographic guidance (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1b Normal hysterosalpingogram: the uterus (u) has a normal contour and shape. The fallopian tubes fill bilaterally with evidence of free spill into the pelvic peritoneum (arrows)

432 |

G. Heinz-Peer |

|

|

2.1.5\ Pathological Findings

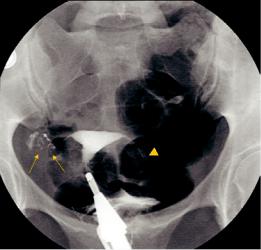

Diverticuli in the isthmic segment of the tube are caused by salpingitis isthmica nodosa (SIN) (Fig. 2). These would be difficult to appreciate by sonography. SIN was described more than 100 years ago as irregular benign extensions of the tubal epithelium into the myosalpinx, associated with reactive myohypertrophy and sometimes inflammation. There is an association between SIN and pelvic inflammatory disease; however, it is not clear whether SIN is caused by pelvic inflammation, or is congenital and predisposes to inflammation.

Obstruction of the tubes can occur anywhere along their length (Fig. 3a–c). Obstruction of the midisthmic portion may be missed by sonography,

Fig. 2 Salpingitis isthmica nodosa: multiple tiny diverticuli in the right isthmic portion (arrows) caused by mucosal proliferation and muscular hypertrophy with mucosal invasion into the muscularis; partial tubectomy on the left side (arrowhead)

because of the small caliber of the tube and the absence of dilation when there is obstruction at this level.

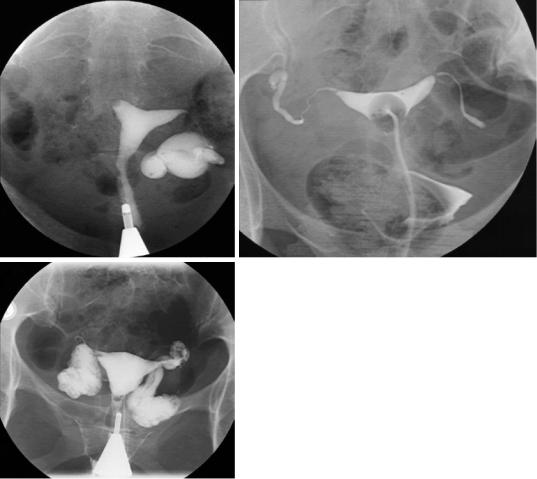

Polyps are small, smooth filling defects, which can be single or multiple, and do not distort the overall size and shape of the uterine cavity (Fig. 4a, b). Leiomyomas are usually single, larger lobulated masses, which only partially project into the cavity, and often enlarge and distort the cavity.

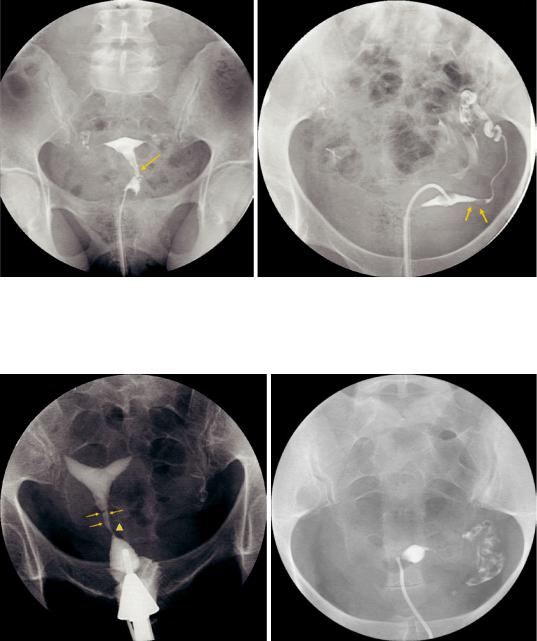

Synechiae are scars that result from uterine trauma such as complications of pregnancy, curettage, uterine surgery, or uterine infection. Synechiae are generally linear and irregular (Fig. 5a) and extend from one wall to the opposite wall allowing contrast agent to flow around them only in one dimension. For this reason, they are more easily defined than the abovementioned masses, which in general allow contrast agent to flow around them in two dimensions. Synechiae may also manifest as absence of filling of the entire uterus or part of it, and can be confused with müllerian defect (Fig. 5b).

Asherman syndrome is defined by the combination of infertility, hypomenorrhea or amenorrhea, and a history of uterine curettage. It is estimated to occur in 68% of infertile women who have undergone two or more curettages (Bacelar et al. 1995). The pathophysiology consists of intrauterine adhesions (synechiae) that develop after traumatic endometrial injury, such as postpartum or postabortion uterine curettage (Fig. 6a, b). Less commonly, it results from endometritis (Kurman and Mazur 1987). It is hypothesized that infertility occurs because uterine adhesions and scarring interfere with sperm migration and embryo implantation.

Evaluation of Infertility |

433 |

|

|

a |

b |

c

Fig. 3 Bilateral fallopian tube obstruction (three different patients): there is dilated, obstructed tube on the left (hydrosalpinx) and obstruction of the right intramural portion (a), nondilated obstruction on both sides at the

isthmic/ampullary portion (b), and huge bilateral dilatation without spill into the peritoneum—bilateral hydrosalpinx (c)

434 |

G. Heinz-Peer |

|

|

a |

b |

Fig. 4 Endometrial polyps: stalked filling defect within the endometrial cavity probably arising from the cervical canal (arrow). Note normal filling of the fallopian tubes and free spill into the peritoneum (a). In a different patient

the hysterosalpingogram shows a filling defect in the intramural portion of the left tube (arrows) causing narrowing but no obstruction; normal filling of the fallopian tubes (b)

a |

b |

Fig. 5 Synechiae: on hysterosalpingogram irregular borders (arrows) and narrowing of the cervical canal (arrowhead) are depicted (a). In a different patient HSG shows synechiae causing partial obstruction of the endometrial

cavity and occlusion of the right fallopian tube (b). Note: HSG may not rule out müllerian duct anomaly with certainty in this particular case