- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Posterior Compartment

- •2.2 Anterior Compartment

- •2.3 Middle Compartment

- •2.4 Perineal Body

- •3 Compartments

- •3.1 Posterior Compartment

- •3.1.1 Connective Tissue Structures

- •3.1.2 Muscles

- •3.1.3 Reinterpreted Anatomy and Clinical Relevance

- •3.2 Anterior Compartment

- •3.2.1 Connective Tissue Structures

- •3.2.2 Muscles

- •3.2.3 Reinterpreted Anatomy and Clinical Relevance

- •3.2.4 Important Vessels, Nerves, and Lymphatics of the Anterior Compartment

- •3.3 Middle Compartment

- •3.3.1 Connective Tissue Structures

- •3.3.2 Muscles

- •3.3.3 Reinterpreted Anatomy and Clinical Relevance

- •3.3.4 Important Vessels, Nerves, and Lymphatics of the Middle Compartment

- •4 Perineal Body

- •References

- •MR and CT Techniques

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2.1 Spasmolytic Medication

- •2.3.2 Diffusion-Weighted Imaging

- •2.3.3 Dynamic Contrast Enhancement

- •3 CT Technique

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Technical Disadvantages

- •3.4 Oral and Rectal Contrast

- •References

- •Uterus: Normal Findings

- •1 Introduction

- •References

- •1 Clinical Background

- •1.1 Epidemiology

- •1.2 Clinical Presentation

- •1.3 Embryology

- •1.4 Pathology

- •2 Imaging

- •2.1 Technique

- •2.2.1 Class I Anomalies: Dysgenesis

- •2.2.2 Class II Anomalies: Unicornuate Uterus

- •2.2.3 Class III Anomalies: Uterus Didelphys

- •2.2.4 Class IV Anomalies: Bicornuate Uterus

- •2.2.5 Class V Anomalies: Septate Uterus

- •2.2.6 Class VI Anomalies: Arcuate Uterus

- •2.2.7 Class VII Anomalies

- •References

- •Benign Uterine Lesions

- •1 Background

- •1.1 Uterine Leiomyomas

- •1.1.1 Epidemiology

- •1.1.2 Pathogenesis

- •1.1.3 Histopathology

- •1.1.4 Clinical Presentation

- •1.1.5 Therapy

- •1.1.5.1 Indications

- •1.1.5.2 Medical Therapy and Ablation

- •1.1.5.3 Surgical Therapy

- •1.1.5.4 Uterine Artery Embolization (UAE)

- •1.1.5.5 Magnetic Resonance-Guided Focused Ultrasound

- •2 Adenomyosis of the Uterus

- •2.1 Epidemiology

- •2.2 Pathogenesis

- •2.3 Histopathology

- •2.4 Clinical Presentation

- •2.5 Therapy

- •3 Imaging

- •3.2 Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- •3.2.1 Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Technique

- •3.2.2 MR Appearance of Uterine Leiomyomas

- •3.2.3 Locations, Growth Patterns, and Imaging Characteristics

- •3.2.4 Histologic Subtypes and Forms of Degeneration

- •3.2.5 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.2.6 MR Appearance of Uterine Adenomyosis

- •3.2.7 Locations, Growth Patterns, and Imaging Characteristics

- •3.2.8 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.3 Computed Tomography

- •3.3.1 CT Technique

- •3.3.2 CT Appearance of Uterine Leiomyoma and Adenomyosis

- •3.3.3 Atypical Appearances on CT and Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1 Indications

- •4.2 Technique

- •Bibliography

- •Cervical Cancer

- •1 Background

- •1.1 Epidemiology

- •1.2 Pathogenesis

- •1.3 Screening

- •1.4 HPV Vaccination

- •1.5 Clinical Presentation

- •1.6 Histopathology

- •1.7 Staging

- •1.8 Growth Patterns

- •1.9 Treatment

- •1.9.1 Treatment of Microinvasive Cervical Cancer

- •1.9.2 Treatment of Grossly Invasive Cervical Carcinoma (FIGO IB-IVA)

- •1.9.3 Treatment of Recurrent Disease

- •1.9.4 Treatment of Cervical Cancer During Pregnancy

- •1.10 Prognosis

- •2 Imaging

- •2.1 Indications

- •2.1.1 Role of CT and MRI

- •2.2 Imaging Technique

- •2.2.2 Dynamic MRI

- •2.2.3 Coil Technique

- •2.2.4 Vaginal Opacification

- •2.3 Staging

- •2.3.1 General MR Appearance

- •2.3.2 Rare Histologic Types

- •2.3.3 Tumor Size

- •2.3.4 Local Staging

- •2.3.4.1 Stage IA

- •2.3.4.2 Stage IB

- •2.3.4.3 Stage IIA

- •2.3.4.4 Stage IIB

- •2.3.4.5 Stage IIIA

- •2.3.4.6 Stage IIIB

- •2.3.4.7 Stage IVA

- •2.3.4.8 Stage IVB

- •2.3.5 Lymph Node Staging

- •2.3.6 Distant Metastases

- •2.4 Specific Diagnostic Queries

- •2.4.1 Preoperative Imaging

- •2.4.2 Imaging Before Radiotherapy

- •2.5 Follow-Up

- •2.5.1 Findings After Surgery

- •2.5.2 Findings After Chemotherapy

- •2.5.3 Findings After Radiotherapy

- •2.5.4 Recurrent Cervical Cancer

- •2.6.1 Ultrasound

- •2.7.1 Metastasis

- •2.7.2 Malignant Melanoma

- •2.7.3 Lymphoma

- •2.8 Benign Lesions of the Cervix

- •2.8.1 Nabothian Cyst

- •2.8.2 Leiomyoma

- •2.8.3 Polyps

- •2.8.4 Rare Benign Tumors

- •2.8.5 Cervicitis

- •2.8.6 Endometriosis

- •2.8.7 Ectopic Cervical Pregnancy

- •References

- •Endometrial Cancer

- •1.1 Epidemiology

- •1.2 Pathology and Risk Factors

- •1.3 Symptoms and Diagnosis

- •2 Endometrial Cancer Staging

- •2.1 MR Protocol for Staging Endometrial Carcinoma

- •2.2.1 Stage I Disease

- •2.2.2 Stage II Disease

- •2.2.3 Stage III Disease

- •2.2.4 Stage IV Disease

- •4 Therapeutic Approaches

- •4.1 Surgery

- •4.2 Adjuvant Treatment

- •4.3 Fertility-Sparing Treatment

- •5.1 Treatment of Recurrence

- •6 Prognosis

- •References

- •Uterine Sarcomas

- •1 Epidemiology

- •2 Pathology

- •2.1 Smooth Muscle Tumours

- •2.2 Endometrial Stromal Tumours

- •3 Clinical Background

- •4 Staging

- •5 Imaging

- •5.1 Leiomyosarcoma

- •5.2.3 Undifferentiated Uterine Sarcoma

- •5.3 Adenosarcoma

- •6 Prognosis and Treatment

- •References

- •1.1 Anatomical Relationships

- •1.4 Pelvic Fluid

- •2 Developmental Anomalies

- •2.1 Congenital Abnormalities

- •2.2 Ovarian Maldescent

- •3 Ovarian Transposition

- •References

- •1 Introduction

- •4 Benign Adnexal Lesions

- •4.1.1 Physiological Ovarian Cysts: Follicular and Corpus Luteum Cysts

- •4.1.1.1 Imaging Findings in Physiological Ovarian Cysts

- •4.1.1.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1.2 Paraovarian Cysts

- •4.1.2.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.1.2.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1.3 Peritoneal Inclusion Cysts

- •4.1.3.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.1.3.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1.4 Theca Lutein Cysts

- •4.1.4.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.1.4.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1.5 Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

- •4.1.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.1.5.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.2.1 Cystadenoma

- •4.2.1.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.2.1.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.2.2 Cystadenofibroma

- •4.2.2.1 Imaging Features

- •4.2.3 Mature Teratoma

- •4.2.3.1 Mature Cystic Teratoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •4.2.3.2 Monodermal Teratoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •4.2.4 Benign Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors

- •4.2.4.1 Fibroma and Thecoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •4.2.4.2 Sclerosing Stromal Tumor

- •Imaging Findings

- •4.2.5 Brenner Tumors

- •4.2.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.2.5.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •5 Functioning Ovarian Tumors

- •References

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Context

- •2.2.2 Indications According to Simple Rules

- •References

- •CT and MRI in Ovarian Carcinoma

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Familial or Hereditary Ovarian Cancers

- •3 Screening for Ovarian Cancer

- •5 Tumor Markers

- •6 Clinical Presentation

- •7 Imaging of Ovarian Cancer

- •7.1.2 Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

- •7.1.3 Ascites

- •7.3 Staging of Ovarian Cancer

- •7.3.1 Staging by CT and MRI

- •Imaging Findings According to Tumor Stages

- •Value of Imaging

- •7.3.2 Prediction of Resectability

- •7.4 Tumor Types

- •7.4.1 Epithelial Ovarian Cancer

- •High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer

- •Low-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer

- •Mucinous Epithelial Ovarian Cancer

- •Endometrioid Ovarian Carcinomas

- •Clear Cell Carcinomas

- •Imaging Findings of Epithelial Ovarian Cancers

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Borderline Tumors

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Recurrent Ovarian Cancer

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Value of Imaging

- •Malignant Germ Cell Tumors

- •Dysgerminomas

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Immature Teratomas

- •Imaging Findings

- •Malignant Transformation in Benign Teratoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Sex-Cord Stromal Tumors

- •Granulosa Cell Tumors

- •Imaging Findings

- •Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumor

- •Imaging Findings

- •Ovarian Lymphoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •7.4.3 Ovarian Metastases

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •7.5 Fallopian Tube Cancer

- •7.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •References

- •Endometriosis

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Sonography

- •3 MR Imaging Findings

- •References

- •Vagina and Vulva

- •1 Introduction

- •3.1 CT Appearance

- •3.2 MRI Protocol

- •3.3 MRI Appearance

- •4.1 Imperforate Hymen

- •4.2 Congenital Vaginal Septa

- •4.3 Vaginal Agenesis

- •5.1 Vaginal Cysts

- •5.1.1 Gardner Duct Cyst (Mesonephric Cyst)

- •5.1.2 Bartholin Gland Cyst

- •5.2.1 Vaginal Infections

- •5.2.1.1 Vulvar Infections

- •5.2.1.2 Vulvar Thrombophlebitis

- •5.3 Vulvar Trauma

- •5.4 Vaginal Fistula

- •5.5 Post-Radiation Changes

- •5.6 Benign Tumors

- •6.1 Vaginal Malignancies

- •6.1.1 Primary Vaginal Carcinoma

- •6.1.1.1 MRI Findings

- •6.1.1.2 Lymph Node Drainage

- •6.1.1.3 Recurrence and Complications

- •6.1.2 Non-squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Vagina

- •6.1.2.1 Adenocarcinoma

- •6.1.2.2 Melanoma

- •6.1.2.3 Sarcomas

- •6.1.2.4 Lymphoma

- •6.2 Vulvar Malignancies

- •6.2.1 Vulvar Carcinoma

- •6.2.2 Melanoma

- •6.2.3 Lymphoma

- •6.2.4 Aggressive Angiomyxoma of the Vulva

- •7 Vaginal Cuff Disease

- •7.1 MRI Findings

- •8 Foreign Bodies

- •References

- •Imaging of Lymph Nodes

- •1 Background

- •3 Technique

- •3.1.1 Intravenous Unspecific Contrast Agents

- •3.1.2 Intravenous Tissue-Specific Contrast Agents

- •References

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.1.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.1.3 Value of Imaging

- •2.2 Pelvic Inflammatory

- •2.2.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.3 Hydropyosalpinx

- •2.3.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.3.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.4 Tubo-ovarian Abscess

- •2.4.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.4.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.4.3 Value of Imaging

- •2.5 Ovarian Torsion

- •2.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.5.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.5.3 Diagnostic Value

- •2.6 Ectopic Pregnancy

- •2.6.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.6.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.6.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.1 Pelvic Congestion Syndrome

- •3.1.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.1.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.1.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.2 Ovarian Vein Thrombosis

- •3.2.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.2.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.2.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.3 Appendicitis

- •3.3.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.3.2 Value of Imaging

- •3.4 Diverticulitis

- •3.4.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.4.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.4.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.5 Epiploic Appendagitis

- •3.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.5.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.5.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.6 Crohn’s Disease

- •3.6.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.6.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.6.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.7 Rectus Sheath Hematoma

- •3.7.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.7.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.7.3 Value of Imaging

- •References

- •MRI of the Pelvic Floor

- •1 Introduction

- •2 Imaging Techniques

- •3.1 Indications

- •3.2 Patient Preparation

- •3.3 Patient Instruction

- •3.4 Patient Positioning

- •3.5 Organ Opacification

- •3.6 Sequence Protocols

- •4 MR Image Analysis

- •4.1 Bony Pelvis

- •5 Typical Findings

- •5.1 Anterior Compartment

- •5.2 Middle Compartment

- •5.3 Posterior Compartment

- •5.4 Levator Ani Muscle

- •References

- •Evaluation of Infertility

- •1 Introduction

- •2 Imaging Techniques

- •2.1 Hysterosalpingography

- •2.1.1 Cycle Considerations

- •2.1.2 Technical Considerations

- •2.1.3 Side Effects and Complications

- •2.1.5 Pathological Findings

- •2.1.6 Limitations of HSG

- •2.2.1 Cycle Considerations

- •2.2.2 Technical Considerations

- •2.2.2.1 Normal and Abnormal Anatomy

- •2.2.3 Accuracy

- •2.2.4 Side Effects and Complications

- •2.2.5 Limitations of Sono-HSG

- •2.3 Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- •2.3.1 Indications

- •2.3.2 Technical Considerations

- •2.3.3 Limitations

- •3 Ovulatory Dysfunction

- •4 Pituitary Adenoma

- •5 Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

- •7 Uterine Disorders

- •7.1 Müllerian Duct Anomalies

- •7.1.1 Class I: Hypoplasia or Agenesis

- •7.1.2 Class II: Unicornuate

- •7.1.3 Class III: Didelphys

- •7.1.4 Class IV: Bicornuate

- •7.1.5 Class V: Septate

- •7.1.6 Class VI: Arcuate

- •7.1.7 Class VII: Diethylstilbestrol Related

- •7.2 Adenomyosis

- •7.3 Leiomyoma

- •7.4 Endometriosis

- •References

- •MR Pelvimetry

- •1 Clinical Background

- •1.3.1 Diagnosis

- •1.3.2.1 Cephalopelvic Disproportion

- •1.3.4 Inadequate Progression of Labor due to Inefficient Contraction (“the Powers”)

- •2.2 Palpation of the Pelvis

- •3 MR Pelvimetry

- •3.2 MR Imaging Protocol

- •3.3 Image Analysis

- •3.4 Reference Values for MR Pelvimetry

- •5 Indications for Pelvimetry

- •References

- •MR Imaging of the Placenta

- •2 Imaging of the Placenta

- •3 MRI Protocol

- •4 Normal Appearance

- •4.1 Placenta Variants

- •5 Placenta Adhesive Disorders

- •6 Placenta Abruption

- •7 Solid Placental Masses

- •9 Future Directions

- •References

- •Erratum to: Endometrial Cancer

392 |

A. Davis and A. Rockall |

|

|

a |

b |

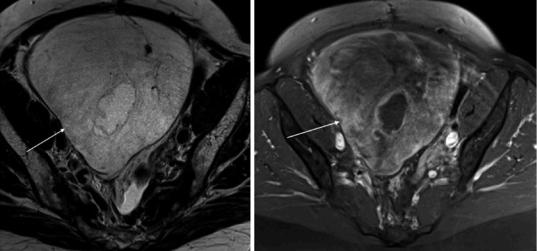

Fig. 12 Massive ovarian edema caused by infiltration from a mucinous colorectal tumor. The large pelvic mass (arrow) is of high signal intensity on axial T2wi (a) and

demonstrates peripheral and heterogeneous contrast enhancement on dynamic contrast-enhanced T1 fat-satu- rated image (b)

assist in further assessment of the adnexa. Rarely, a calcified mass may result from chronic infarction which cannot reliably be differentiated from a calcified ovarian tumor (Currarino and Rutledge 1989). Malignant massive ovarian edema may be seen when there is metastatic infiltration of the lymphatics of the ovary (Krasevic et al. 2004; Bazot et al. 2003) (Fig. 12).

2.5.3\ Diagnostic Value

Early diagnosis and treatment is crucial to prevent irreversible ovarian damage and prevent infectious complications. Most patients with suspected torsion clinically and on sonography will undergo immediate surgical untwisting. However, in patients that present with severe acute pain of uncertain diagnosis, CT may be the first line investigation and the signs of ovarian torsion may be difficult to appreciate. MRI and CT are often used in clinically atypical cases, especially in chronic torsion. In early torsion, the imaging signs may be indicative but not specific of ovarian torsion. MRI and CT are particularly useful in detecting twisted lesions displaced outside the pelvis,

where sonography may be limited. In pregnancy and in children, MRI is the modality of choice to further assess suspected ovarian torsion.

2.6\ Ectopic Pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy describes implantation and growth of the fertilized ovum at any site other than the endometrial cavity. The fallopian tube accounts for the vast majority of all ectopic gestations (95%), with 75% found in the ampulla and the remainder occurring in the fimbrial and isthmic portions with roughly equal distribution (Bouyer et al. 2002). Rarely, ectopic pregnancy may occur within the ovary (3.2%), or within the peritoneal cavity (1.3%). Ectopic cervical pregnancy is more commonly found in pregnancies achieved through in vitro fertilization technologies (Ushakov et al. 1997). The major cause of ectopic pregnancy is disruption of normal tubal patency due to infection, surgery, müllerian anomalies, or tumors. The rise of ectopic pregnancies in the last decade is

Acute and Chronic Pelvic Pain Disorders |

393 |

|

|

a |

b |

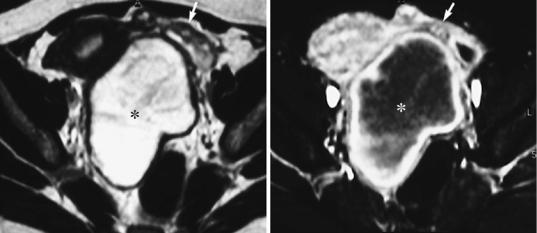

Fig. 13 Hematosalpinx in ectopic tubal pregnancy. Transaxial T2WI (a) and contrast-enhanced T1WI with fat saturation (FS) (b). In a 27-year-old woman with a positive pregnancy test, a cystic adnexal mass (asterisk) displaces the uterus. There is widening of the endometrial cavity. The adnexal lesion is separated from the adjacent

left ovary (arrow) and displays inhomogeneous signal intensity with areas of high and low SI on T2WI (a) indicative of hemorrhage. The cystic content of the fallopian tube and distinct homogenous tubal wall enhancement is demonstrated following contrast media administration (b). Courtesy of Dr. Teresa Margarida Cunha, Lisbon

associated with the increased incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease. A history of PID with chronic salpingitis is found in 35–50% of patients with ectopic pregnancy.

2.6.1\ Imaging Findings

On MRI, tubal wall enhancement and fresh tubal hematoma are highly specific for ectopic tubal pregnancy (Kataoka et al. 1999) (Fig. 13). The gestational sac is a cystic, centrally fluid-filled structure that is surrounded by a thick-walled peripheral rim. The latter displays inhomogeneous signal intensity on T2WI and medium signal intensity on T1WI, which may contain small areas of high signal intensity suggestive of blood (Nishino et al. 2002). When such a gestational sac-like structure is found separate from the uterus without tubal structures, this finding is equivocal due to the differential diagnostic problems of cystic ovarian masses (Kataoka et al. 1999). Identification of the uterine junctional zone between the gestational sac surrounded by myometrium and the uterine cavity is highly suggestive of a rare type of ectopic pregnancy, interstitial pregnancy (Filhastre et al. 2005). In

suspected ectopic pregnancy, the combination of an adnexal mass and acute intraperitoneal hemorrhage is suggestive of tubal rupture.

2.6.2\ Differential Diagnosis

In women of reproductive age presenting with elevated human chorionic gonadotropin levels, demonstration of a gestational sac-like structure is highly suggestive of ectopic pregnancy. However, ovarian cancer may rarely be detected during early pregnancy and be misdiagnosed as ectopic pregnancy (Riley et al. 1996). Based on the MRI findings alone, ectopic pregnancy may be misdiagnosed as an ovarian mass, e.g., ovarian cancer or endometriosis. Interstitial ectopic pregnancy may resemble cystic adenomyomas or necrotic leiomyomas (Filhastre et al. 2005).

2.6.3\ Value of Imaging

The diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is usually established by the combination of the clinical history, β-HCG levels, and transvaginal sonography. The role of MRI has not been defined. It may, however, provide additional information in the case of equivocal ultrasound,