- •Foreword

- •Table of contents

- •Figures

- •Tables

- •Boxes

- •1. Executive summary

- •Energy system transformation

- •Special focus 1: The cost-effectiveness of climate measures

- •Special focus 2: The Electricity Market Reform

- •Special focus 3: Maintaining energy security

- •Key recommendations

- •2. General energy policy

- •Country overview

- •Institutions

- •Supply and demand trends

- •Primary energy supply

- •Energy production

- •Energy consumption

- •Energy policy framework

- •Energy and climate taxes and levies

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •3. Energy and climate change

- •Overview

- •Emissions

- •GHG emissions

- •Projections

- •Institutions

- •Climate change mitigation

- •Emissions targets

- •Clean Growth Strategy

- •The EU Emissions Trading System

- •Low-carbon electricity support schemes

- •Climate Change Levy

- •Coal phase-out

- •Energy efficiency

- •Low-carbon technologies

- •Adaptation to climate change

- •Legal and institutional framework

- •Evaluation of impacts and risks

- •Response measures

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •4. Renewable energy

- •Overview

- •Supply and demand

- •Renewable energy in the TPES

- •Electricity from renewable energy

- •Heat from renewable energy

- •Institutions

- •Policies and measures

- •Targets and objectives

- •Electricity from renewable energy sources

- •Heat from renewable energy

- •Renewable Heat Incentive

- •Renewable energy in transport

- •Assessment

- •Electricity

- •Transport

- •Heat

- •Recommendations

- •5. Energy efficiency

- •Overview

- •Total final energy consumption

- •Energy intensity

- •Overall energy efficiency progress

- •Institutional framework

- •Energy efficiency data and monitoring

- •Regulatory framework

- •Energy Efficiency Directive

- •Other EU directives

- •Energy consumption trends, efficiency, and policies

- •Residential and commercial

- •Buildings

- •Heat

- •Transport

- •Industry

- •Assessment

- •Appliances

- •Buildings and heat

- •Transport

- •Industry and business

- •Public sector

- •Recommendations

- •6. Nuclear

- •Overview

- •New nuclear construction and power market reform

- •UK membership in Euratom and Brexit

- •Waste management and decommissioning

- •Research and development

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •7. Energy technology research, development and demonstration

- •Overview

- •Energy research and development strategy and priorities

- •Institutions

- •Funding on energy

- •Public spending

- •Energy RD&D programmes

- •Private funding and green finance

- •Monitoring and evaluation

- •International collaboration

- •International energy innovation funding

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •8. Electricity

- •Overview

- •Supply and demand

- •Electricity supply and generation

- •Electricity imports

- •Electricity consumption

- •Institutional and regulatory framework

- •Wholesale market design

- •Network regulation

- •Towards a low-carbon electricity sector

- •Carbon price floor

- •Contracts for difference

- •Emissions performance standards

- •A power market for business and consumers

- •Electricity retail market performance

- •Smart grids and meters

- •Supplier switching

- •Consumer engagement and vulnerable consumers

- •Demand response (wholesale and retail)

- •Security of electricity supply

- •Legal framework and institutions

- •Network adequacy

- •Generation adequacy

- •The GB capacity market

- •Short-term electricity security

- •Emergency response reserves

- •Flexibility of the power system

- •Assessment

- •Wholesale electricity markets and decarbonisation

- •Retail electricity markets for consumers and business

- •The transition towards a smart and flexible power system

- •Recommendations

- •Overview

- •Supply and demand

- •Production, import, and export

- •Oil consumption

- •Retail market and prices

- •Infrastructure

- •Refining

- •Pipelines

- •Ports

- •Storage capacity

- •Oil security

- •Stockholding regime

- •Demand restraint

- •Assessment

- •Oil upstream

- •Oil downstream

- •Recommendations

- •10. Natural gas

- •Overview

- •Supply and demand

- •Domestic gas production

- •Natural gas imports and exports

- •Largest gas consumption in heat and power sector

- •Natural gas infrastructure

- •Cross-border connection and gas pipelines

- •Gas storage

- •Liquefied natural gas

- •Policy framework and markets

- •Gas regulation

- •Wholesale gas market

- •Retail gas market

- •Security of gas supply

- •Legal framework

- •Adequacy of gas supply and demand

- •Short-term security and emergency response

- •Supply-side measures

- •Demand-side measures

- •Gas quality

- •Recent supply disruptions

- •Interlinkages of the gas and electricity systems

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •ANNEX A: Organisations visited

- •Review criteria

- •Review team and preparation of the report

- •Organisations visited

- •ANNEX B: Energy balances and key statistical data

- •Footnotes to energy balances and key statistical data

- •ANNEX C: International Energy Agency “Shared Goals”

- •ANNEX D: Glossary and list of abbreviations

- •Acronyms and abbreviations

- •Units of measure

2. GENERAL ENERGY POLICY

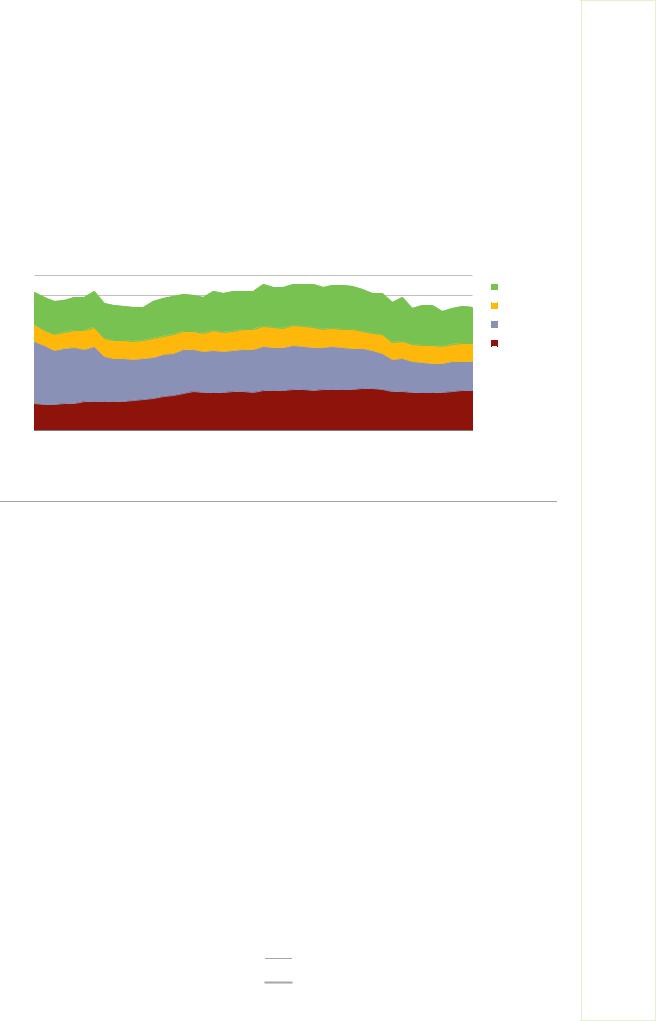

Energy consumption

In 2017, the United Kingdom’s TFC was 127 Mtoe, 11% lower than in 2007. The largest drop in TFC was in the industry sector, falling by 22%, whereas the residential sector decreased its consumption by 11% and the transport and commercial sectors remained relatively stable. Since 2014, energy consumption in all sectors saw a slight rebound. The transport sector is the largest energy-consuming sector (33% of TFC in 2017), mainly road transport. The residential sector is the second largest (29%) with industry the third (24%), as illustrated in Figure 2.8.

Figure 2.8 TFC by sector, 1973-2017

160.0 |

Mtoe |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Residential |

|

140.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commercial* |

|

120.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Industry** |

|

100.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Transport |

|

80.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

60.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

40.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1973 |

1977 |

1981 |

1985 |

1989 |

1993 |

1997 |

2001 |

2005 |

2009 |

2013 |

2017 |

The transport sector is the largest energy consumer with 32% of TFC and the total energy consumption slightly increased in recent years.

*Commercial includes commercial and public services, agriculture, and forestry.

**Includes non-energy consumption.

Source: IEA (2019), World Energy Balances 2019 First edition (database), www.iea.org/statistics/.

Energy policy framework

The United Kingdom has an integrated energy and climate policy framework and maintains a strong international leadership on climate change, electricity (and gas) market reforms, and the security of supply.

During 2012-16, the energy and climate policy framework was geared towards implementing a major reform to support the security of supply and the decarbonisation of the power sector. Building on the 2012 White Paper on the Electricity Market Reform (or EMR, see UK Government, 2012), the Energy Act 2013 introduced four mechanisms to support investment in low-carbon electricity generation: a carbon price floor, an emissions performance standard, a capacity market (CM) and contracts for difference (CFDs). In addition to the EMR, the government also announced, on 18 November 2015, the closure of all coal-fired power plants without carbon capture and storage (unabated coal) by 2025.

Since 2016, the United Kingdom has streamlined its energy and climate policies towards efforts to strengthen the innovation, productivity, and competitiveness of the industry. This is reflected in the new institutional governance, with the integration of the energy and climate portfolio into a wider, newly created department, BEIS.

25

ENERGY INSIGHTS

IEA. All rights reserved.

2. GENERAL ENERGY POLICY

The United Kingdom has been at the forefront of recognising climate change threats and adopting regulations and policy solutions to support low-carbon investment. Based on the UK’s Climate Change Act (the Act), adopted in 2008, the UK targets emissions reductions by at least 80% by 2050 on 1990 levels. Under the Act, the government has to set legally binding five-year caps on emissions – carbon budgets – 12 years in advance and then to publish a report with policies and measures to meet that budget and the previous ones. Five carbon budgets have been set to date; the fifth one was set in July 2016 and covers the period 2028-32.

The Clean Growth Strategy, adopted in October 2017, outlined a large number of proposals to meet the fifth carbon budget through measures across the economy and in targeted sectors – transport, business and industry, residential, the heat and the power sector, and agriculture and forestry. The Strategy was underpinned by a pledge to invest British pounds (GBP) 2.5 billion in low-carbon innovation over five years (UK Government, 2017a):

•Accelerate the shift to low-carbon transport by working with industry under the Automotive Sector Deal, ending the sales of new conventional petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2040, developing a charging network across the UK, including through public funding and legal obligations under the Automated and Electric Vehicles Bill, as well as supporting the take-up of ultra low emission vehicles (ULEV) and low-emission taxis and buses, based public funding, including GBP 1 billion to support consumers to afford a ULEV.

•Improve energy efficiency in business and industry by at least 20% by 2030, including through an Industrial Energy Efficiency scheme for large companies, strengthened energy efficiency standards in new and existing commercial buildings and rented property, joint industrial decarbonisation and energy efficiency action plans, international and domestic actions to deploy carbon capture, usage, and storage (CCUS) and other GHG removal technologies,

•Improve the energy efficiency of homes, including by providing investment support to upgrade around one million homes through the Energy Company Obligation (ECO), stronger standards for new buildings, upgrading all fuel poor homes to Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) Band C by 2030 and as many homes as possible to be EPC Band C by 2035.

•Foster the roll-out of low-carbon heating by reforming the Renewable Heat Incentive, phasing out carbon-intensive fossil fuel heating (in new buildings off the gas grid) as well as recycling of industrial process heat, building and extending heat networks with public funding and develop new energy efficiency and heating technologies based on innovation funding.

•Deliver clean, smart, and flexible power through measures to reduce costs for households and businesses (price cap, reform of NG to an independent system operator), phasing out the use of unabated coal to produce electricity by 2025; delivering new nuclear power (Hinkley Point C and a new pipeline of projects), improving the route to market for renewable technologies, such as offshore wind, through a Sector Deal and another round of auctions for contracts of difference with public funding of around GBP 560 million, as well as providing certainty of the total carbon price in the power sector.

•Enhance the benefits and value of the UK’s natural resources to focus better on environmental outcomes, including addressing climate change more directly, through a Resources and Waste Strategy, new agriculture support and boost larger-scale woodland and forest creation as well as UK timber production.

26

IEA. All rights reserved.

2. GENERAL ENERGY POLICY

•Lead in the public sector with a voluntary public sector target of 30% reduction in carbon emissions by 2021, the promotion of government leadership in clean growth and the green finance capabilities, including green mortgages and the creation of a Green Finance Taskforce.

The Industrial Strategy of 2017 (UK Government, 2017b) aims to boost productivity, innovation, and prosperity, to bring down the costs of UK decarbonisation policies, and to upgrade energy infrastructure in line with the next generation of technologies. As part of the Strategy, the government is building long-term strategic partnerships with businesses, the so-called sector deals. To date, sector deals are agreed for the nuclear and automotive industries, among others. The Budget 2018 announced a GBP 315 million Industrial Energy Transformation Fund.

The Clean Growth Strategy and the Industrial Strategy refocused the energy policy framework towards competitiveness and affordability. The government has adopted a long-term roadmap to minimise business and household energy costs, which started with the cost of energy review in 2017, the reform of the levy control and various initiatives to bring down the cost of achieving decarbonisation in the power and industrial sectors. The government is adapting existing support schemes to support further reductions in line with decreases in technology costs (for offshore wind), while ensuring planned investments are delivered, notably through the CFD.

The government commissioned an independent review into the cost of energy led by Professor Dieter Helm, who recommended ways to deliver the carbon targets and ensure the security of supply at a minimum cost (Helm, 2017). Helm underlines that the various low-carbon support schemes have contributed to the high cost of electricity. He recommends a single economy-wide carbon price coupled with carbon border tariffs (which adjust for the trade impacts of a UK carbon system different to that of the European Union Emissions Trading System [EU ETS]), abolishing existing RES/CFD support schemes in favour of firm energy capacity auctions, encouraging flexible capacity and renewables investment, and moving to competition for energy networks (instead of regulation).

Energy and climate taxes and levies

The United Kingdom has a levy control framework (LCF) in place, linked to the annual budget process, to control the costs of low-carbon electricity support schemes, which are levied on consumers’ energy bills through wholesale prices. The framework covers electricity only and no other sectors, such as transport or heat. The LCF includes the costs of the CFD, the renewables obligation (RO), and the feed-in tariff (FIT) scheme, as well as early CFDs awarded under the “final investment decisions enabling for renewables” process.

In the autumn of 2017, the United Kingdom introduced a Control for Low Carbon Levies (“the Control”) to replace the LCF. The Control covers all existing and new low-carbon electricity levies. The government decided not to introduce new low-carbon electricity levies until the level of existing costs (“legacy cost”) falls. Based on the government’s forecast, this means there will be no new low-carbon electricity levies until 2025. The existing schemes covered by the Control will continue. The announced government’s commitments – including up to GBP 557 million (in 2011/12 prices) for further CFDs (May 2019 CFD Pot 2) – have been confirmed. According to updated forecasts published

27

ENERGY INSIGHTS

IEA. All rights reserved.

2. GENERAL ENERGY POLICY

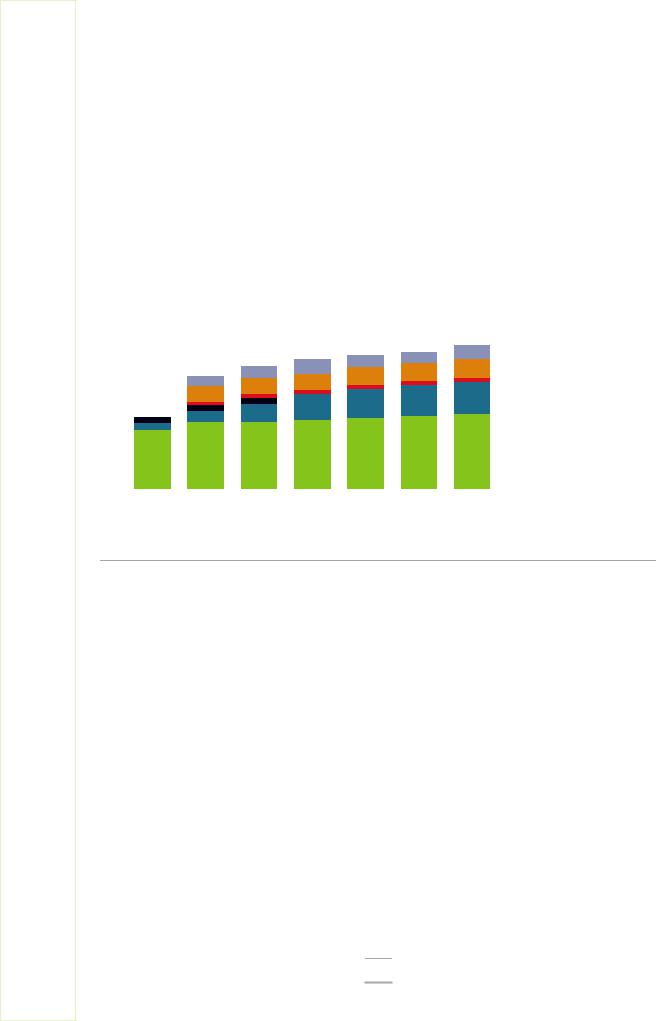

by the Office for Budget Responsibility in October 2018, low-carbon levies will reach GBP 10.2 billion in 2020/21, which is equivalent to GBP 8.0 billion in 2020/21 in 2011/12 prices, not counting the warm home discount, CM, or FITs (Figure 2.9).

In Great Britain, the Total Carbon Price (TCP) for energy generation is made up of the EU Emissions Trading System ETS price and the Carbon Price Support (CPS) rate of the Climate Change Levy (CCL). The CPS was implemented to support the EU ETS and underpins the price of carbon at a level that drives low-carbon investment by taxing fossil fuels used to generate electricity. The CPS rate does not apply to energy generators in Northern Ireland. HM Treasury confirms CPS rates in advance of the delivery of the Budget, and all revenue from the CPS is retained by the Treasury. In 2018-19, the revenue is forecast to be around GBP 0.9 billion.

Figure 2.9 Environmental levies forecasts

14 |

GPB billion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Capacity market* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FiTs* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Warm home discount* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CRC Energy Efficiency scheme |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Contracts for difference |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Renewables obligation |

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2017 / 18 |

2018 / 19 |

2019 / 20 |

2020 / 21 |

2021 / 22 |

2022 / 23 |

2023 / 24 |

|

|

|

|||||||||

The RO is forecast to provide the largest environmental levy, but the CFDs will grow the most.

* The Office of National Statistics has yet to include the warm home discount, FITs and CM auctions in their outturn numbers. If included, they would have been GBP 0.3 billion, GBP 1.4 billion, and GBP 0.2 billion, respectively.

Note: CRC = Carbon Reduction Commitment.

Source: UK Government (2018d), Economic and Fiscal Outlook – March 2018, Supplementary Fiscal Table 2.7, https://cdn.obr.uk/EFO-MaRch_2018.pdf.

The CPS was introduced in 2013/14 at a rate of GBP 4.94 per tonne of carbon dioxide (GBP/tCO2). In the budget of 2014, the government announced that the CPS rate would be capped at 18 GBP/tCO2 from 2016/17 to 2020/21 to limit the competitive disadvantage faced by businesses and to reduce energy bills for consumers. In the Budget of 2016, the cap was maintained at 18 GBP/tCO2 from 2016/17 to 2019/20. In the Budget of 2018, the government announced that CPS rates will be frozen at 18 GBP/CO2 in 2020/21 following the rise in the EU ETS price. From 2021/22, the government will seek to reduce CPS rates if the TCP remains high.

Introduced in 2001, the CCL is levied on the supply of energy (generators) to business and public sector consumers (households, charities, and most small businesses are excluded) per unit of energy used in four commodities (electricity, gas, coal, and liquefied petroleum gas). Energy-intensive industries have a discount on the CCL if they meet negotiated energy efficiency targets through voluntary agreements (Climate Change Agreements [CCAs]). This relief currently provides a 90% discount on the levy on

28

IEA. All rights reserved.