- •Foreword

- •Table of contents

- •Figures

- •Tables

- •Boxes

- •1. Executive summary

- •Energy system transformation

- •Special focus 1: The cost-effectiveness of climate measures

- •Special focus 2: The Electricity Market Reform

- •Special focus 3: Maintaining energy security

- •Key recommendations

- •2. General energy policy

- •Country overview

- •Institutions

- •Supply and demand trends

- •Primary energy supply

- •Energy production

- •Energy consumption

- •Energy policy framework

- •Energy and climate taxes and levies

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •3. Energy and climate change

- •Overview

- •Emissions

- •GHG emissions

- •Projections

- •Institutions

- •Climate change mitigation

- •Emissions targets

- •Clean Growth Strategy

- •The EU Emissions Trading System

- •Low-carbon electricity support schemes

- •Climate Change Levy

- •Coal phase-out

- •Energy efficiency

- •Low-carbon technologies

- •Adaptation to climate change

- •Legal and institutional framework

- •Evaluation of impacts and risks

- •Response measures

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •4. Renewable energy

- •Overview

- •Supply and demand

- •Renewable energy in the TPES

- •Electricity from renewable energy

- •Heat from renewable energy

- •Institutions

- •Policies and measures

- •Targets and objectives

- •Electricity from renewable energy sources

- •Heat from renewable energy

- •Renewable Heat Incentive

- •Renewable energy in transport

- •Assessment

- •Electricity

- •Transport

- •Heat

- •Recommendations

- •5. Energy efficiency

- •Overview

- •Total final energy consumption

- •Energy intensity

- •Overall energy efficiency progress

- •Institutional framework

- •Energy efficiency data and monitoring

- •Regulatory framework

- •Energy Efficiency Directive

- •Other EU directives

- •Energy consumption trends, efficiency, and policies

- •Residential and commercial

- •Buildings

- •Heat

- •Transport

- •Industry

- •Assessment

- •Appliances

- •Buildings and heat

- •Transport

- •Industry and business

- •Public sector

- •Recommendations

- •6. Nuclear

- •Overview

- •New nuclear construction and power market reform

- •UK membership in Euratom and Brexit

- •Waste management and decommissioning

- •Research and development

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •7. Energy technology research, development and demonstration

- •Overview

- •Energy research and development strategy and priorities

- •Institutions

- •Funding on energy

- •Public spending

- •Energy RD&D programmes

- •Private funding and green finance

- •Monitoring and evaluation

- •International collaboration

- •International energy innovation funding

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •8. Electricity

- •Overview

- •Supply and demand

- •Electricity supply and generation

- •Electricity imports

- •Electricity consumption

- •Institutional and regulatory framework

- •Wholesale market design

- •Network regulation

- •Towards a low-carbon electricity sector

- •Carbon price floor

- •Contracts for difference

- •Emissions performance standards

- •A power market for business and consumers

- •Electricity retail market performance

- •Smart grids and meters

- •Supplier switching

- •Consumer engagement and vulnerable consumers

- •Demand response (wholesale and retail)

- •Security of electricity supply

- •Legal framework and institutions

- •Network adequacy

- •Generation adequacy

- •The GB capacity market

- •Short-term electricity security

- •Emergency response reserves

- •Flexibility of the power system

- •Assessment

- •Wholesale electricity markets and decarbonisation

- •Retail electricity markets for consumers and business

- •The transition towards a smart and flexible power system

- •Recommendations

- •Overview

- •Supply and demand

- •Production, import, and export

- •Oil consumption

- •Retail market and prices

- •Infrastructure

- •Refining

- •Pipelines

- •Ports

- •Storage capacity

- •Oil security

- •Stockholding regime

- •Demand restraint

- •Assessment

- •Oil upstream

- •Oil downstream

- •Recommendations

- •10. Natural gas

- •Overview

- •Supply and demand

- •Domestic gas production

- •Natural gas imports and exports

- •Largest gas consumption in heat and power sector

- •Natural gas infrastructure

- •Cross-border connection and gas pipelines

- •Gas storage

- •Liquefied natural gas

- •Policy framework and markets

- •Gas regulation

- •Wholesale gas market

- •Retail gas market

- •Security of gas supply

- •Legal framework

- •Adequacy of gas supply and demand

- •Short-term security and emergency response

- •Supply-side measures

- •Demand-side measures

- •Gas quality

- •Recent supply disruptions

- •Interlinkages of the gas and electricity systems

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •ANNEX A: Organisations visited

- •Review criteria

- •Review team and preparation of the report

- •Organisations visited

- •ANNEX B: Energy balances and key statistical data

- •Footnotes to energy balances and key statistical data

- •ANNEX C: International Energy Agency “Shared Goals”

- •ANNEX D: Glossary and list of abbreviations

- •Acronyms and abbreviations

- •Units of measure

8. ELECTRICITY

Supplier switching

The Energy Switch Guarantee was launched in June 2016 and provides consumers with the right to switch suppliers within 21 days. Ofgem is working to implement reliable and fast switching through a centralised gas and electricity switching service. In 2018, the annual switching rate was about 18.4%, a very high rate by comparison with other IEA EU countries, which means five out of six households did not switch energy supplier in the previous 12 months (between October 2016 and September 2017) (Ofgem, 2018a). However, more than 60% of households only switched once or never and around 54% were on default tariffs for more than 3 years.

Consumer engagement and vulnerable consumers

Focus on the energy poor and vulnerable consumers has been strong in the United Kingdom. Despite the reduction in real terms of the average dual fuel bill since its peak in 2013, many consumers still worry about the level of their energy bills. Vulnerable customers are more likely to be on expensive standard variable tariffs, despite being less able to afford them. In 2016 – the latest year with available data – 11% of the customers, which represents 2.5 million households in England, were living in fuel poverty. Financial support is given to pensioners and the elderly, in particular the Warm Home Discount Scheme and Winter Fuel Payment.

Demand response (wholesale and retail)

The GB electricity market has advanced demand-side flexibility thanks to the rising deployment of demand-side response (DSR) and increased storage participation in contracted markets. However, retail market DSR remains limited as consumers are not yet able to benefit from DSR because smart meters are not yet fully rolled out. NG’s “Power Responsive” programme promoted DSR or storage from industry and large energy users through innovative Information technology platforms or aggregators. In the T-4 CM auction for capacity in the 2021/2022 delivery year, 1.2 GW (2.4%) came from DSR. Half of the accepted capacity was from dispatchable generation, DSR through load shifting, onsite generation or storage, and stand-alone storage.

Security of electricity supply

IEA in-depth reviews focus on the adequacy dimension of electricity security, which includes generation and network adequacy. Adequacy in the GB context refers to the physical capability of the power system to generate and transport electricity to meet consumers’ demand. This section also includes an assessment of the challenges and opportunities that stem from the integration of larger shares of variable renewables into the system. In the GB context, flexibility refers to the ability of the system to respond to changes in demand or supply to avoid disruption and limit price spikes. Provided here is a short overview of the legal framework for the security of electricity supply, emergency preparedness, and response for electricity in the United Kingdom.

Legal framework and institutions

BEIS is in charge of the security of electricity supply together with NG and Ofgem. NG needs to ensure the overall power supply meets the demand and that the system stays

149

ENERGY SECURITY

IEA. All rights reserved.

8. ELECTRICITY

within the frequency required. Ofgem monitors the security of supply on a regular basis, also as part of the State of the Energy Market reports.

BEIS sets the reliability standard for the GB electricity market equivalent to a loss of load expectation (LOLE)3. Since 2013, the LOLE has been set at 3 hours per year (or around a 5% margin of capacity over peak demand), which balances the cost of additional capacity against the costs that a consumer would face if there was ever a shortage in supply. The reliability standard is legislated in Regulation 6 of the Electricity Capacity Regulations 2014 and is used to determine how much capacity the government will procure in the CM auctions annually.

NG monitors the adequacy of demand and supply and models the outlook for both, using NG’s Future Energy Scenarios (NG, 2017). Based on this least-worst regrets assessment of a variety of different scenarios and sensitivities, NG makes an annual assessment of how much capacity is needed to meet the reliability standard. This assessment accounts for the amount of capacity provided by power plants that are not eligible for capacity payments, such as low-carbon generation in receipt of other government support. It is the basis of a recommendation to the Secretary of State for BEIS in its annual Electricity Capacity Report.

The Secretary of State also takes advice from an independent Panel of Technical Experts (PTE) before deciding on the final target for the auctions. The PTE impartially scrutinises and quality assures the analysis of NG. It provides an independent view on NG’s methodology (PTE, 2017). Alongside the decision on auction targets, the BEIS Secretary of State must also set the non-target parameters that determine the slope of the demand curve. BEIS establishes a cycle for running CM auctions, and has been reviewing and improving the mechanism.

The United Kingdom has a National Emergency Plan: Downstream Gas and Electricity, which sets out the national arrangements established between the government, the electricity industry, Ofgem, the European Commission, and other interested parties for the safe and effective management of electricity supply emergencies.

Network adequacy

NG also plans network investment needs across Great Britain for the period of ten years ahead, set out in its annual Electricity Ten Year Statement (ETYS) and related Network Options Assessment. The latest ETYS indicates that high north-south flows across Scotland and the north of England to the Midlands and the south are increasing and network adequacy needs to evolve in step (National Grid Electricity Systems Operator, 2018a).

The Winter Outlook of NG ESO also assesses the short term electricity security situation and possible network and generation shortages (NG ESO, 2018b).

Most recently, the Western HVDC project to link south-west Scotland to north Wales added 2.2 GW to the network. Staffel (2018) estimates that by Q1 2018 the link had already helped NG save around GBP 9 million per month on constraint payments.

3 This is the number of hours per annum in which, over the long term, it is statistically expected that supply will not meet demand through the market without mitigating actions being taken by the system operator.

150

IEA. All rights reserved.

8. ELECTRICITY

Generation adequacy

Peak electricity demand in Great Britain was 61 GW in 2016. National Grid’s future scenarios assesses generation adequacy in the medium to longer term (NG, 2017). NG’s scenarios estimate electricity demand to remain flat, but projects GB peak demand to rise (Table 8.5). Under NG’s “Two Degrees” scenario peak demand could be 62 GW in 2020 and 65 GW in 2030. The forecast electricity demand is higher depending on the speed of electrification of heat and transport, consumer behaviour around the use and uptake of EVs, and smart charging appliances (“Consumer power” scenario). Overall, capacity margins have come down in the United Kingdom since 2010, with the retirements of coal and slow progress on nuclear new builds. In recent years, the capacity reserve margin was around 20%.

Table 8.5 Evolution of peak demand (GW)

Scenario |

|

Electricity year beginning |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2016 |

2020 |

2030 |

|

|

|

|

History |

61 |

|

|

Two Degrees |

61 |

62 |

65 |

|

|

|

|

Slow Progression |

61 |

60 |

61 |

Steady State |

61 |

61 |

61 |

|

|

|

|

Consumer Power |

61 |

62 |

66 |

|

|

|

|

Table 8.6 Cumulative new capacity (GW) for all power producers by fuel type

Fuel type |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coal |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coal and natural gas CCS |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oil |

0.00 |

0.20 |

0.35 |

0.82 |

0.94 |

0.94 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Natural gas |

0.00 |

1.02 |

1.73 |

2.27 |

3.83 |

3.83 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nuclear |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other thermal |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Renewables |

3.59 |

6.93 |

8.30 |

9.76 |

11.60 |

15.14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Interconnectors |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

5.80 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Storage |

0.00 |

0.21 |

0.21 |

0.21 |

0.60 |

0.60 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total cumulative new build |

3.59 |

8.36 |

11.58 |

14.06 |

19.96 |

26.31 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: NG (2017), Reference Scenario, also available under www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/666266/Annex-k-total-cumulative-new- capacity.xls.

The GB capacity market

Based on the Energy Act of 2013, the Electricity Capacity Regulations came into force in 2014 for Great Britain (Ireland has its own CM) with a first CM auction in December 2014. The main objective of the CM was to ensure security of supply and close the anticipated supply gap related to the large-scale retirement of old coal and NPPs. All types of capacity (and technology, including demand response, storage, and interconnectors) are able to participate, except for capacity providers already in receipt of

151

ENERGY SECURITY

IEA. All rights reserved.

8. ELECTRICITY

support from other policy measures (most importantly renewable energy). Existing diesel and coal generators can participate in the CM until 2024. Capacity payments are determined via competitive auctions, held four years (T-4 auction) and one year (T-1 auction, which tops up the targeted capacity) before the delivery period. In total, there were four T-4 auctions and a special early auction (T-1 auction), with clearing prices that ranged from GBP 6.95 kilowatts per year (GBP/kW/yr) to 22 GBP/kW/yr. The CM has cleared increasing amounts of new capacity – in the December 2016 auction 3.4 GW and in January 2018 2.9 GW, mostly new interconnectors. The share of open cycle gas turbines (OCGTs) being awarded capacity remuneration in T-4 auctions has been in decline (but up in T-1 auctions).

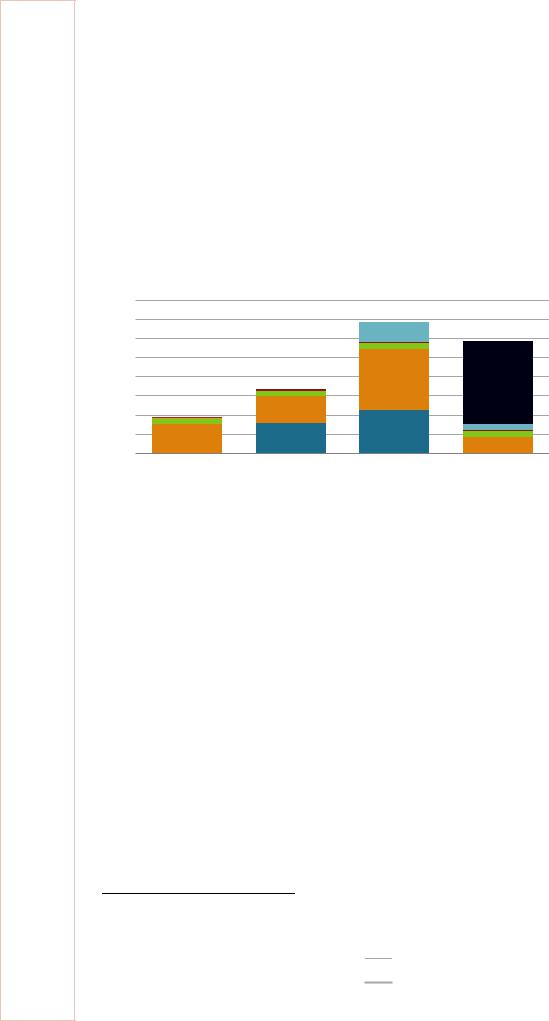

Figure 8.14 New build capacity by fuel and technology in T-4 CM auctions

MW

4 000

3 500

3 000

2 500

2 000

1 500

1 000

500

0

2014 T-4 auction |

2015 T-4 auction |

2016 T-4 auction |

2017 T-4 auction |

*Oil refers to oil generation and reciprocating engines.

Interconnector

Interconnector

Oil*

Oil*

Storage

Storage

Co-generation and

Co-generation and

autogeneration

Coal and biomass

Coal and biomass

OCGT

OCGT

CCGT

CCGT

Notes: 2017 T-4 auction refers to the auction in January 2018. OCGT = Open Cycle Gas Turbine; CCGT = Combined Cycle Gas Turbine.

Source: Ofgem (2018b), Annual Report on the Operation of the Capacity Market in 2017/18, https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/system/files/docs/2018/08/20180802_annual_report_on_the_operation_of_cm_201718_final.pdf.

The government was keen that the CM should allow for new gas-fired power plants. Todate, the CM has secured over 5.4 GW of new build capacity for delivery between 2018/19 and 2021/22 (Figure 8.14 and Table 8.6). This includes a new combined cycle gas turbine (CCGT) plant (at Kings Lynn), a new OCGT plant (at Spalding), and a significant number of small-scale gas engines, but so far only the Carrington CCGT (800 MW) is in commission (since 2017).

The most recent T-4 auction secured in total 50.41 GW of capacity at a cost of 8.40 GBP/kW/yr from 2017/18 through to 2021/2022 (Ofgem, 2018b). Most of the cleared capacity in this T-4 auction was from existing generators (86%) and interconnectors (BritNed, IFA, and Moyle). The three new interconnector projects (ElecLink, IFA2, and Nemo Link) were awarded contracts, too. In terms of fuels, 46% were CCGTs, 16% nuclear and 9% co-generation4. The T-4 auction for 2021/22 had 6 GW of unabated coal capacity secured agreements (Drax and Ratcliffe) and 4 GW did not secure agreements.

4 Co-generation refers to the combined production of heat and power.

152

IEA. All rights reserved.

8. ELECTRICITY

Battery storage was successful for the first time in December 2016, with a 500 MW clearing for delivery in 2020/21. DSR has come forward through the CM, with 1.4 GW and 1.2 GW clearing in the previous two main auctions, respectively. At the same time, the inclusion of these technologies is not straightforward (in terms of de-rating factors, availability, and penalties). Large amounts of storage, DSR, and embedded generation did not clear the T-4 2017.

In 2018/19, the forecast LOLE is 0.001 hours, much below the three-hour standard (NG ESO, 2018b). Electricity supply has consistently been more reliable than the standard (with fewer market actions needed by NG) as NG consistently underestimates the contribution from the demand side (Ofgem, 2018b). NG recently evaluated that the risk of loss of load is much lower than 3 hours (in fact, only 45 minutes) with the start of the halfhour settlement in the wholesale market and acknowledged that it underestimates the distributed generation, battery and EVs, demand response, and on-site generation.

In terms of participating companies, the share of the Big Six has been falling in favour of small-scale generation companies (so-called embedded generation), which were highly competitive as they were able to avoid transmission network usage charges. The CM arguably over-encouraged the entry of embedded generation (connected to the distribution grid), which do not pay but receive the TNUoS. Ofgem decided to cut the Triad payment to reduce these embedded benefits, and the court confirmed Ofgem’s decision against Peak Gen Power in June 2018.

The Great Britain CM is now in a standstill period, and NG postponed the upcoming T-4 and T-1 auctions for delivery years 2022/23 and 2019/20 after the ruling of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) on 15 November 2018, which annulled the state aid clearance for the CM on the grounds that the European Commission should have conducted a more extensive investigation before granting approval, in particular of certain DSR-related elements of the scheme. The judgement does not challenge the design of the Great Britain CM as such. Since Tempus filed its complaint with the ECJ, the CM has undergone several adjustments and reforms. The ruling halts capacity payments until the European Commission grants a new approval. Among other aspects, Tempus argued that the European Commission had not fully investigated issues that relate to the design of the Great Britain CM as to the treatment of DSR in the CM, and discrimination in the contract length.

Procedure – Tempus argued that the European Commission could not conclude that the CM did not have a problem as to its compatibility with the internal market given the procedure followed, as there was no distinction between the preliminary stage and the investigation stage.

Length of discussion – Tempus’s view was that the length of the discussion was insufficient to reach every dissenting opinion.

Assessment of the DSR in the CM – Tempus argued that the entry threshold of 2 MW should not be the same for DSR and for generators.

Discrimination against DSR – Tempus claimed that maximum one-year contract period for DSR is unfair when the generation can get periods up to 3 or 15 years. Tempus claimed that to impose the same amount of bid bond to DSR causes an “entry barrier” for DSR.

153

ENERGY SECURITY

IEA. All rights reserved.