- •Foreword

- •Table of contents

- •Figures

- •Tables

- •Boxes

- •1. Executive summary

- •Energy system transformation

- •Special focus 1: The cost-effectiveness of climate measures

- •Special focus 2: The Electricity Market Reform

- •Special focus 3: Maintaining energy security

- •Key recommendations

- •2. General energy policy

- •Country overview

- •Institutions

- •Supply and demand trends

- •Primary energy supply

- •Energy production

- •Energy consumption

- •Energy policy framework

- •Energy and climate taxes and levies

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •3. Energy and climate change

- •Overview

- •Emissions

- •GHG emissions

- •Projections

- •Institutions

- •Climate change mitigation

- •Emissions targets

- •Clean Growth Strategy

- •The EU Emissions Trading System

- •Low-carbon electricity support schemes

- •Climate Change Levy

- •Coal phase-out

- •Energy efficiency

- •Low-carbon technologies

- •Adaptation to climate change

- •Legal and institutional framework

- •Evaluation of impacts and risks

- •Response measures

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •4. Renewable energy

- •Overview

- •Supply and demand

- •Renewable energy in the TPES

- •Electricity from renewable energy

- •Heat from renewable energy

- •Institutions

- •Policies and measures

- •Targets and objectives

- •Electricity from renewable energy sources

- •Heat from renewable energy

- •Renewable Heat Incentive

- •Renewable energy in transport

- •Assessment

- •Electricity

- •Transport

- •Heat

- •Recommendations

- •5. Energy efficiency

- •Overview

- •Total final energy consumption

- •Energy intensity

- •Overall energy efficiency progress

- •Institutional framework

- •Energy efficiency data and monitoring

- •Regulatory framework

- •Energy Efficiency Directive

- •Other EU directives

- •Energy consumption trends, efficiency, and policies

- •Residential and commercial

- •Buildings

- •Heat

- •Transport

- •Industry

- •Assessment

- •Appliances

- •Buildings and heat

- •Transport

- •Industry and business

- •Public sector

- •Recommendations

- •6. Nuclear

- •Overview

- •New nuclear construction and power market reform

- •UK membership in Euratom and Brexit

- •Waste management and decommissioning

- •Research and development

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •7. Energy technology research, development and demonstration

- •Overview

- •Energy research and development strategy and priorities

- •Institutions

- •Funding on energy

- •Public spending

- •Energy RD&D programmes

- •Private funding and green finance

- •Monitoring and evaluation

- •International collaboration

- •International energy innovation funding

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •8. Electricity

- •Overview

- •Supply and demand

- •Electricity supply and generation

- •Electricity imports

- •Electricity consumption

- •Institutional and regulatory framework

- •Wholesale market design

- •Network regulation

- •Towards a low-carbon electricity sector

- •Carbon price floor

- •Contracts for difference

- •Emissions performance standards

- •A power market for business and consumers

- •Electricity retail market performance

- •Smart grids and meters

- •Supplier switching

- •Consumer engagement and vulnerable consumers

- •Demand response (wholesale and retail)

- •Security of electricity supply

- •Legal framework and institutions

- •Network adequacy

- •Generation adequacy

- •The GB capacity market

- •Short-term electricity security

- •Emergency response reserves

- •Flexibility of the power system

- •Assessment

- •Wholesale electricity markets and decarbonisation

- •Retail electricity markets for consumers and business

- •The transition towards a smart and flexible power system

- •Recommendations

- •Overview

- •Supply and demand

- •Production, import, and export

- •Oil consumption

- •Retail market and prices

- •Infrastructure

- •Refining

- •Pipelines

- •Ports

- •Storage capacity

- •Oil security

- •Stockholding regime

- •Demand restraint

- •Assessment

- •Oil upstream

- •Oil downstream

- •Recommendations

- •10. Natural gas

- •Overview

- •Supply and demand

- •Domestic gas production

- •Natural gas imports and exports

- •Largest gas consumption in heat and power sector

- •Natural gas infrastructure

- •Cross-border connection and gas pipelines

- •Gas storage

- •Liquefied natural gas

- •Policy framework and markets

- •Gas regulation

- •Wholesale gas market

- •Retail gas market

- •Security of gas supply

- •Legal framework

- •Adequacy of gas supply and demand

- •Short-term security and emergency response

- •Supply-side measures

- •Demand-side measures

- •Gas quality

- •Recent supply disruptions

- •Interlinkages of the gas and electricity systems

- •Assessment

- •Recommendations

- •ANNEX A: Organisations visited

- •Review criteria

- •Review team and preparation of the report

- •Organisations visited

- •ANNEX B: Energy balances and key statistical data

- •Footnotes to energy balances and key statistical data

- •ANNEX C: International Energy Agency “Shared Goals”

- •ANNEX D: Glossary and list of abbreviations

- •Acronyms and abbreviations

- •Units of measure

3. ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE

Given the cancellation of new nuclear projects in the UK in 2018-19, however, the role of nuclear will decline and the importance of imports increase. However, uncertainty over the future regime of interconnectors in a Brexit scenario might undermine investments and efficient operation of interconnectors and increase the price of power imports, as explained in the Chapter on Electricty.

Institutions

The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) is responsible, among other issues, for national energy and climate policies and to promote international action to address climate change. BEIS was created in July 2016 as a result of a merger between the former Department of Energy and Climate Change and Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) is in charge of environmental policy and regulations, which include those for air quality, waste, water, and domestic adaptation. Defra works with BEIS to ensure specific government policies on low-carbon energy and decarbonisation measures are sustainable and aligned with Defra’s environmental objectives. The Office for Low Emission Vehicles (OLEV) is a joint unit between BEIS and the Department for Transport that supports the early market for ultra-low emission vehicles (ULEVs).

Established under the UK Climate Change Act 2008, the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) is an independent advisory body with the task to advise the government and devolved administrations on emissions targets, to monitor and report to the parliament on meeting emissions targets and carbon budgets, and to conduct independent analysis into climate change science, economics, and policy. The CCC comprises a chairperson and eight independent members. The CCC is jointly sponsored by BEIS, the Northern Ireland Executive, the Scottish government, and the Welsh government. The CCC includes the Adaptation Sub-Committee (ASC), also established under the Climate Change Act 2008, to advice the CCC and report on the progress in adaptation. Its work is led by a chairperson, who also sits on the CCC, and six expert members. It is jointly sponsored by Defra, the Northern Ireland Executive, the Scottish government, and the Welsh government.

The Natural Capital Committee (NCC) is an independent advisory committee that provides advice to the government on the sustainable use of natural resources, i.e. forests, rivers, land, minerals, and oceans. The NCC’s remit also includes air quality, clean water, and hazard protection.

Established by the Cabinet Office, the National Infrastructure Resilience Council brings together utility companies to share information about the locations of their assets and to take a coordinated approach to flood resilience.

Climate change mitigation

Emissions targets

The United Kingdom’s Climate Change Act, adopted in 2008, established the United Kingdom’s very ambitious legally binding target to reduce GHG emissions by at least 80% by 2050 on 1990 levels. This target is more ambitious than the target of the

39

ENERGY SYSTEM TRANSFORMATION

IEA. All rights reserved.

3. ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE

European Union and its member countries of at least a 40% domestic reduction in GHG emissions by 2030 compared to 1990. The UK government recently sought the advice of the Committee on Climate Change on the implications of the Paris Agreement for the UK’s long-term emissions target, including on setting a net zero target. Their advice was published on 2 May 2019 and recommended that the UK government set a net zero greenhouse gas target for 2050 (CCC, 2019a).

To achieve the long-term national target, the government is obliged to set legally binding five-year caps on emissions – “carbon budgets” – 12 years in advance and then to publish a report with policies and measures to meet that budget and the previous ones. The first carbon budget covered the period 2008-12. Budget levels are set for four further periods: 2013-17 inclusive, 2018-22, 2023-27, and 2028-32. In July 2016, the government set the fifth carbon budget (2028-32) at a level of 1 725 MtCO2e, equivalent to an average 57% reduction on the 1990 emissions.

The CCC advises the government and the Devolved Administrations on setting and meeting carbon budgets. The United Kingdom’s performance against its 2050 target and carbon budgets is assessed through the United Kingdom’s net carbon account, measured in tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent. The United Kingdom met the first carbon budget with headroom of 36 MtCO2e and met its second carbon budget with a headroom of 384 MtCO2e. It is projected to meet the third carbon budgets (CCC, 2019b). To meet the fourth and fifth carbon budgets, additional measures will be needed, as discussed below.

Although covered by the Climate Change Act, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland have separate climate change policies.

In Scotland, the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 commits Scotland to a 42% reduction in emissions by 2020 from 1990 levels and annual reductions between 2010 and 2050. The Scottish government introduced a more ambitious Climate Change Plan and the related Climate Change Act in 2018, which increased the target for the reduction of GHG emissions from 80% by 2050 to 90% and have recently pledged to set a net zero target by 2045, in line with the recommendation of the CCC. At the same time, Scotland will produce a second Scottish Climate Change Adaptation Programme to update the first programme of 2014.

Wales passed the Environment (Wales) Act in 2016, which provides for the setting of GHG emission reduction targets to 2050, including at least an 80% reduction (compared with 1990 levels) in 2050, and five-yearly carbon budgets. The first two carbon budgets (from 2016 to 2020 and 2021 to 2025) were set in December 2018.

The Northern Ireland Executive, in its Programme for government (2011-15), has set a target to continue to work towards reducing its GHG emissions by at least 35% (compared with 1990 levels) by 2025.

Clean Growth Strategy

The UK Clean Growth Strategy sets out proposals to meet the fourth and fifth carbon budgets, while maintaining economic growth and affordability for consumers (UK Government, 2017a). Under the fifth carbon budget (2028-32), the United Kingdom aims at a reduction of 57% on 1990 levels. The government estimates that the combination of existing policies and new measures outlined in this Strategy could deliver over 90% of

40

IEA. All rights reserved.

3. ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE

the required level of emissions savings for the fifth carbon budget, against the 1990 baseline. The carbon budgets do not provide for sectoral targets and are designed to encourage technology neutrality and emission reductions across the economy. However, the Clean Growth Strategy does set out polices by sector with subsectoral goals and objectives, contributing to an illustrative pathway for each sector.

The key challenges identified by the government in meeting these targets relate to 1) decarbonising beyond the power sector (transport, heat, and industry), 2) delivering affordable energy, and 3) establishing a post-Brexit framework (Box 3.1).

When assessing the Clean Growth Strategy, the CCC found a risk to the delivery of existing policies because of insufficient funding and judges the emission reductions from new proposals and intentions in the Clean Growth Strategy to bear a high risk. The CCC also identified a policy gap (CCC, 2018a), in which the existing potential for cost-effective emissions reduction policy has not been explored. Such a cost-effective path as defined by the CCC actually outperforms the carbon budgets. The whole gap would not need to be filled to meet the legislated fourth and fifth budgets. As such, it provides room for manoeuvre or a contingency to meeting longer-term targets.

The CCC concludes that the United Kingdom should significantly reduce the risks of underdelivery of existing policies, notably in car fuel efficiency, carbon capture, usage and storage, and nuclear generation, and bring forward new fully funded policies. The CCC urges the government to put in place contingency plans in case major infrastructure projects are delayed or cancelled. It also recommends introducing new policies and measures to address the sectoral imbalance in emissions reductions, as well as to make better use of low-cost opportunities to reduce emissions (often in areas of proven technology and established markets, such as onshore wind, renovation, and energy efficiency) (CCC, 2018b).

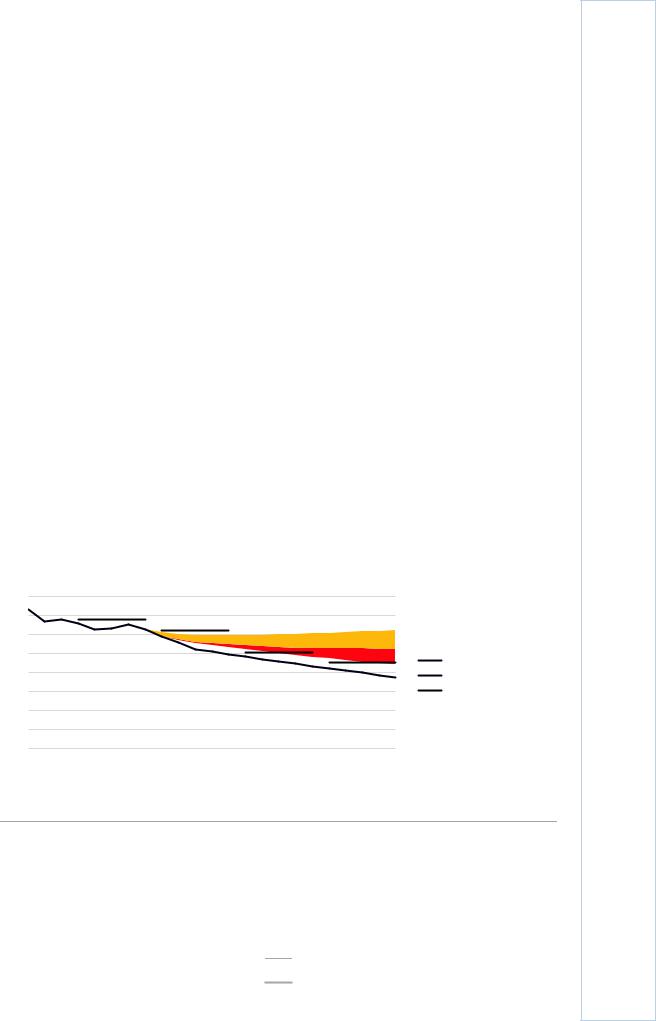

Figure 3.9 Gaps and risks to meet the fourth and fifth carbon budgets

MtCO2e/year

400

350 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

300 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

250 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

200 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

150 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2010 |

2012 |

2014 |

2016 |

2018 |

2020 |

2022 |

2024 |

2026 |

2028 |

2030 |

2032 |

Policies with delivery risks

Policies with delivery risks  Proposals and intentions Policy gap

Proposals and intentions Policy gap

Cost-effective path Historic emissions Legislated carbon budgets

Despite projected reductions in emissions compared to a baseline, there remains a gap towards the cost-effective emissions reduction path that needs to be covered with new policy.

Notes: The figure includes only emissions in the ‘non-traded’ sector (i.e. sources of emissions not covered by the EU ETS), as it is these emissions that determine whether or not a carbon budget is met.

Source: CCC (2018b), Reducing UK emissions 2018: Progress Report to Parliament, June, London, https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/CCC-2018-Progress-Report-to-Parliament.pdf

41

ENERGY SYSTEM TRANSFORMATION

IEA. All rights reserved.

3. ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE

Box 3.1 Climate Change Committee’s recommendations at a glance

Support the simple, low-cost options

Low-cost, low-risk options to reduce emissions are not being supported by government. This penalises the consumer. There is no route to market for cheap onshore wind; withdrawal of incentives has cut home insulation installations to 5% of their 2012 level; woodland creation falls short of stated government ambition in every part of the United Kingdom. Worries over the short-term cost of these options are misguided. The wholeeconomy cost of meeting the legally binding targets will be higher without cost-effective measures in every sector.

Commit to effective regulation and strict enforcement

Tougher long-term standards, for construction and vehicle emissions for example, can cut emissions, while driving consumer demand, innovation, and cost reduction. Providing long line of sight to new regulation also reduces the overall economic costs of compliance. Regulations must also be enforced to be effective: the consumer is cheated when their car’s fuel consumption and real emissions exceed the quoted test-cycle numbers; or when high energy bills are locked-in for generations when stated building standards are not enforced.

End the chopping and changing of policy

A number of important programmes have been cancelled in recent years at short notice, including Zero Carbon Homes and the CCS Commercialisation Programme. This has led to uncertainty, which carries a real cost. A consistent policy environment keeps investor risk low, reduces the cost of capital, provides clear signals to the consumer and gives businesses the confidence to build UK-based supply chains.

Act now to keep long-term options open

An 80% reduction in emissions has always implied the need for new national infrastructure – to transport and store CO2 for example, or to provide decarbonised heat. The deep emissions reductions implied by the Paris Agreement make these developments even more important. It is hard to define the 2050 systems for carbon capture, zero-carbon transport, hydrogen or electrification of heat, but the government must now demonstrate it is serious about their future deployment. Key technologies should be pulled through to bring down costs and support the growth of the low-carbon goods and services sector.

Source: CCC (2018a) An Independent Assessment of the UK’s Clean Growth Strategy: From Ambition to Action, Londonhttps://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CCC-Independent-Assessment-of-UKs- Clean-Growth-Strategy-2018.pdf.

In its progress report of 2018, the CCC concluded that the United Kingdom is not on track to meet its legally binding fourth and fifth carbon budgets (delivery gap). The CCC also asked the government make use of all low-cost options available (policy gap), to commit to an effective and stable regulation and strict enforcement, and to act now to keep all the long-term technology options open.

42

IEA. All rights reserved.