aJZgKak957

.pdf

comparable with that of the best Persian carpets, is apt to cease when greater realism is attempted. These gospels themselves contain, besides the purely decorative pages, four inferior and semi-realistic designs depicting the Evangelists with their symbols, which have clearly been imitated from some work in the Byzantine tradition, Byzantium, which had long been a centre for receiving and passing on ideas, had acquired from the East many purely decorative traditions and had also retained some of the mannerisms of ancient Greek art, together with a far off echo of the Greek sculpturesque sense.

All this was being handed on by degrees to the various nations of Europe, partly through the medium of the South Italians, who had been among the first to imbibe these traditions. In England in the ninth century, the Northumbrian civilisation and all knowledge of the arts were swept away by the Danish wars.

The liveliest centre of culture in Western Europe was now the court of Charlemagne (771-814) and his successors. Carolingian illuminators borrowed many of their motifs from Irish and English illuminations in the Irish tradition. These motifs were again recopied from Carolingian manuscripts by Saxon illuminators who did not know of their Celtic origin. Thus a Celtic border occurs in the frontispiece of Bede's Life of St. Cuthbert.

But the chief sources that inspired Carolingian illuminators were Byzantine and later Classical manuscripts. From the latter they acquired some second-hand knowledge of ancient Greek and Roman traditions. Out of these mingled elements a Carolingian style was formed, from which were developed the styles of most of the painting of Northern and Western Europe. The Carolingians could also be lively illustrators.

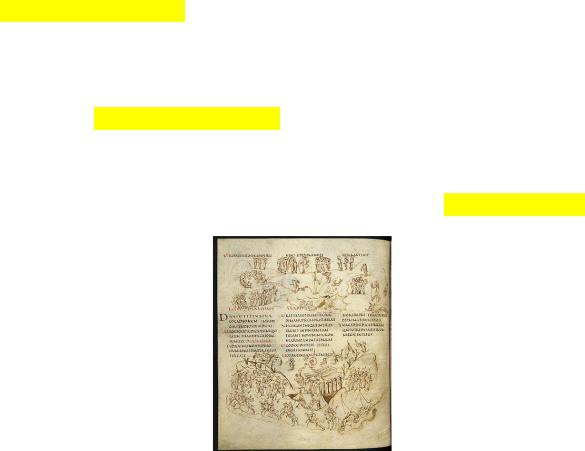

In the Utrecht Psalter produced at Rheims, there are hasty little pen sketches of figures in violent action, often ill-proportioned but intensely alive and vivid. They may partly have been derived from late Classical realistic work, but suggest also that the artist was an observer of contemporary life. The Utrecht Psalter came to England early in the tenth century and was eagerly imitated by Anglo-Saxon illuminators, whose taste for vigorous anecdote it exactly suited.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/72/Utrecht104.jpg/340pxUtrecht104.jpg

31

The Utrecht Psalter. Start of Psalm 71

Carolingian influence came into England largely because of the friendship between Alfred and Charlemagne. The Psalter of Athelstan, Alfred's grandson shows some timid attempts to absorb the Carolingian style; and the already mentioned frontispiece to Bede's Life of St. Cuthbert is a bolder work of the same date. But it was at Winchester under St. Aethelwold, reformer, scholar and bishop, that English illumination seriously began. The style of the Winchester school, in contrast to that of the Celtic tradition, depended upon speed rather than accuracy. Its sources were almost entirely Carolingian. Illustration was as much its aim as decoration.

In the earliest Winchester illumination, the gaily coloured frontispiece to King Edgar's Charter, New Minster, Winchester, the style is already fully developed. The king offers a book to Christ, who is seated above in a 'glory' surrounded by angels with the fluttering draperies characteristic of Winchester illuminations. On either side of the king stand the Virgin and Saint Peter. The masterpiece of Winchester art of this period is the famous Benedictional of St. Aethelwold in the Duke of Devonshire's possession.

The artist uses a more rapid method of execution than that of the Lindisfarne illuminator, but shows an almost equal power of decorative invention. Most of the borders of his important pages are rectangular, but some are enclosed by columns supporting a gable, a trefoil arch or one or more round arches. In the page illustrating the Baptism of Christ, a classical motif occurs: a figure lying beside the river Jordan, just as Father Tiber might appear in a Roman bas-relief.

The illustration to the Adoration of the Magi shows the importance in this type of work of linear pattern. Each line of drapery flows rhythmically into the next. With these lines are contrasted those of the foliage, of the architecture and of the streaky clouds - a contrast which introduces a richness akin to that supplied by colour.

Side by side with such more costly work, the illuminators of Winchester produced other books with rapid illustrations in pen-outline. One is an actual copy of the Utrecht Psalter. Others suggest that the artist has been observing contemporary life. In this type of work, masses of colour, if they occur at all, are not applied opaquely as in the Benidictional of St. Aethelwold, but in transparent washes. This pen-and-wash method reappears in thirteenth-century illumination. The love of something fresh and delicate that is also final and not to be retouched seems always to have appealed to the English mind.

Illustrations to books, both of this kind and of the type of those in the Benedictional, continued to be produced by the artists of Winchester, and by their imitators in cities like Canterbury up to the time of the Norman Conquest. After that event the arts were for a time discouraged. But by about 1100 English illumination began to revive, until in the course of the century England had become a leader in that art, from whom even France was willing to learn.

32

At first however English art was much more closely connected with that of the Continent than it had been in Saxon times. Norman painting and Norman architecture had much in common. A heavy splendour was the aim of both. Illuminators covered their pages with masses of gold, orange vermilion and ultramarine, often producing a gaudier and less harmonious effect than was obtained by the subtler colours of the Saxons. The style can be seen in the Bury St. Edmunds Bible (1121-1148).

The Guthlac Roll shows a revival of the old Winchester method of lively outline drawing, in this case combined with unusual linear firmness and decorative invention.

Secondly, in the University Library, Cambridge, there is a Bestiary or book about animals, (a form of literature just coming into fashion at this time) in which some sailors are landing upon a whale which they have mistaken for an island. This again shows a return to humour and anecdote.

Thirdly, there is the Psalter of Westminster Abbey with its grandly monumental designs and schemes of colour, far more harmonious than those in the same opaque method in the Bury Bible. This psalter may be regarded as mainly Norman in style.

Fourthly, there is the great Winchester Bible belonging to the Winchester Cathedral library, in which designs of active figures in the old Saxon tradition are painted with the gaudier opaque colours that the Normans had introduced.

To this period belong the earliest preserved wall paintings in churches. These are not strictly frescoes, since fresh plaster was not applied to the wall. Instead the existing plaster walls were thoroughly saturated with water and the pigments applied mixed with lime, tempered where necessary with other vehicles, such as egg. This method continued to be employed in mural decoration in England up to the fifteenth century. Of later twelve century date are the geometrical and floral patterns in Ely and St. Albans Cathedrals and in many other Norman churches.

Figure subjects are not so frequent, but Sussex contains a number of churches where they are still decipherable. At Hardham, little more than the beauty of the original colour can be seen; but at Clayton some bold groups of stately figures can with patience be discerned and enjoyed. In Gloucestershire, St Mary's Church at Kempley still retains some of its glory.

The best preserved paintings of this time are in Canterbury Cathedral. The ceiling of St. Gabriel's in the Crypt painted about 1180 is still rich with brilliant reds, blues and yellows. In the central 'glory' is a seated Christ surrounded by four flying angels. Around and beneath are biblical scenes in all of which an angel takes part. The movement in the draperies of the four who fly, recalls the old Winchester drawings, and is more closely allied to contemporary Canterbury illuminations.

In Canterbury Cathedral also, high up on a wall in St. Anselm's Chapel is the masterpiece of this period. St. Paul at Malta is feeding a fire with sticks and

33

the viper is alighting upon his hand - an incident seldom depicted. No photograph does this painting justice. Only by climbing a ladder can the fire and the sticks in the Saint's hand be seen or the viper as a paler blue than the blue background.

Early Gothic Painting

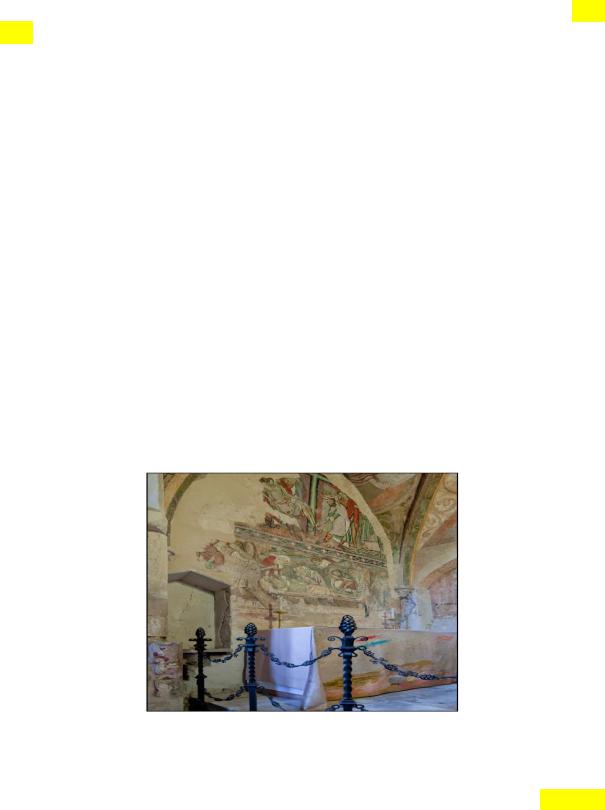

The close of the twelfth century was a period of great promise which bore fruit in the early thirteenth. A number of wall paintings of the early thirteenth century remain. The finest of all are in Winchester Cathedral in the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre. In them the summit of achievement of the Winchester school is reached. No one visiting the cathedral would expect to find masterpieces in this small chapel, crouching beneath the weight of the organ. The building itself is like a low vaulted sepulchre with pointed arches. The ceiling paintings are inferior to the best work which is upon the walls and which belongs to about the year 1225. These are damaged and difficult to see. The light is bad.

To return to the Holy Sepulchre paintings, on the wall seen as you look eastwards, in the arched shape above is painted the Deposition of Christ. Below is the Entombment. On the wall looking north, above are the Entry into Jerusalem and the Raising of Lazarus, and below the Descent into Hell and

Christ appearing to Mary Magdalene. In both tragic scenes the background of sky is a hopeless grey. In the two joyous outdoor scenes it is a pure blue contrasted with reds and yellows. In these the details have mostly gone, but the design of the Entry into Jerusalem is pleasing, and in the Noli Me Tangere, wonder and dawning hope are expressed in every line of Mary Magdalene's kneeling body and outstretched hands. There is enough left of the Entombment to reveal a magnificent and moving composition, though it is the most destroyed. The Deposition is almost complete.

http://m0.i.pbase.com/o5/03/310803/1/129673160.I5293DWX.WinchesterCath_DSC4809.jpg

The subject has been depicted since with more realistic knowledge, sometimes with as sincere feeling, but never with more conviction. In fact it is upon the whole the most powerful of all English wall paintings. The disciples

34

are in the depths of despair; their Master is dead; there is no more hope; Nicodemus wrenches the nail from the cross; Joseph of Arimathea runs forward to support the body whose dead weight falls passively into his arms; the soldier is converted; and the Virgin and St. John wring their hands, their faces distorted with grief. On the face of the Saviour, the marks of a violent struggle are followed by the repose of death. The enlargement of the head, though smaller than the original, will give some idea of its beauty and of the method of modelling.

The face is split up into defined planes of white, pale yellow-ochre and slightly darker grey. The outline is in a dark dull red. This outline alone remains in the equally expressive head of Christ in the Entombment below. The draperies are modelled in a similar way to the heads, but with even greater freedom in the strokes of a large brush. The total design is a good example of rhythm of line.

Wherever possible one long curve is continued into the next. To these flowing curves the straight lines of the cross act as a foil. The colour scheme is entirely expressive; the greys have a touch of green in them; a band of brightish red runs round the arched frame and behind certain figures; the other colours are dull yellows, greens and browns and the deep dull red of the main outlines. Moreover all these decorative qualities are inevitably inspired by the dramatic intensity of the conception.

Although these paintings adorn a chapel with pointed arches, they have more in common with earlier work in the Byzantine tradition than with paintings in the style usually termed Gothic. Gothic tendencies coming over from France affected English architecture first and then painting. The first pointed arch occurred in France in 1140, but Byzantine tendencies lingered in English painting as late as 1260. The new style depended on more than one tendency. Grace and refinement were the Gothic aims rather than weight and apparent strength.

Buildings became taller, arches pointed, columns more slender; lettering in books became narrow and angular; figures in painting and in sculpture became more elegant and less massive. The Gothic arch encouraged a larger proportion of window space in churches, so that artists who would earlier have been wall painters, devoted their time to stained glass or illumination instead.

Also the tendency of stained glass designers to divide spaces up into small shapes such as lozenges or circles with a scene enclosed in each, was imitated by those who painted in books and on walls.

A third tendency of Gothic art was towards naturalism, that is towards the minutely careful rendering of single forms. Painters and sculptors would copy the shape of a flower or leaf, of a bird or beast with a precision never known before. It seems to have been the Franciscan movement that first inspired this awakened love of Nature. In England all these changes took place more gradually than in France, so that it was not until the fourteenth century that the

35

new style was fully developed in painting. Thus traces of the old tradition are evidently mingled with the newer lighter style in the two paintings of about 1260 - a fact which bears out the claim of certain historians that in England alone there was no sudden break from Byzantine to Gothic styles, but that painting developed steadily from the one to the other.

In the thirteenth century France and England were equally important leaders in the arts. Under Louis IX (1226-1270) French art reached its zenith of graceful perfection. At the same time Henry III (1216-1272) was not behind him in patronage of architecture, sculpture and painting. In fact no other English king, except perhaps Charles I, did so much to encourage artistic talent.

The paintings produced in Henry's reign were not all of the same character. There was one school that closely imitated French work, while at the same time another group kept alive the older traditions. Nor was France without her debts to England; for French illuminators especially early in the century were constantly borrowing from English illuminations of the paintings of this period. The gradual change that took place during the century can be seen by comparing the paintings at Winchester in the Chapel of the Guardian Angels with those in the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre already described. The later work, which is easier to see, exactly suits its setting.

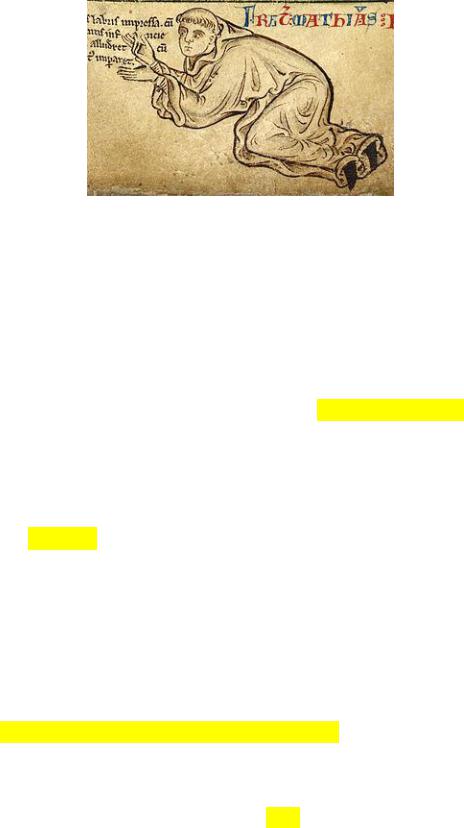

Painting has now reached a more emotional stage, as can be seen by the way in which the movement of the crucified Christ is suggested by the pronounced curve of the body. St. Albans was of even greater importance in Henry III's reign for its school of illumination. The leading spirit was the famous Matthew Paris, a monk of high culture, a scribe, traveller, politician and an unusually enlightened historian. It seems nearly certain that the drawings in pen outline in his books are by his own hand. That of the Virgin and Child is the dedicatory frontispiece to his Historia Anglorum. The script of the Latin words 'O felicia oscula etc' is his own and the kneeling monk below represents himself.

The conception is exquisite. The queenly but motherly Virgin is embraced by her loving Son, who presses his face against hers and throws his arms around her neck. Mistakes in proportion or in spatial relations do not prevent the design from fully expressing the sentiment. There is considerable observation too in the drawing of the sturdy body of the Child, supported by His Mother's arm. Byzantine traditions still linger in the massive proportions of the Virgin, in the drawing of her eyes and in the type of the throne. The naturalistic of details of drapery shows the influence of the newer Gothic fashions. But the method of execution by pen outline with transparent washes added is a survival of the practice of the old Winchester artists before the Conquest.

All the drawings in Matthew Paris' books have been executed with the same freshness and enjoyment. He had a large following and it is probable that his influence is responsible for some of the best thirteenth century English work.

36

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/88/BritLibRoyal14CVIIFol006rM attParisSelfPort.jpg/320px-BritLibRoyal14CVIIFol006rMattParisSelfPort.jpg

Self portrait of Matthew Paris from the original manuscript of his Historia Anglorum (London, British Library, MS Royal 14.C.VII, folio 6r).

A fine Apocalypse is ascribed to his school. Apocalyptic subjects were illustrated in the thirteenth century for the first time in England, and these English designs became the models for such work upon the Continent. The influence of Matthew Paris spread as far as Norway. In 1248 he was sent to reform the Benedictine monastery at Nidesholm and it is probable that a painting of St. Peter once at Faaburg and now in the Christiania Museum is by his own hand. Many other Norwegian paintings of the day are clearly indebted in style to the school of S. Albans; Norwegian culture owing at this time much to England because of the friendship between Henry III and King Haakon (1217-1263).

Belonging also to the middle of the thirteenth century are some striking paintings, mostly in the outline method, on the walls of the nave of West Chiltington Church, Sussex, which contains also some twelfth century work over an arch. In the choir of Rochester Cathedral is painted a Wheel of Fortune of about the same date; nearly half of it was destroyed by restorers; but of what remains the brilliant colouring of scarlets and yellows and olive greens is in wonderful preservation. The drawing, if crude, is vigorous. The little king at the top of the wheel seems to know that he will not stay there long.

Besides these examples, an appreciable number of paintings of this period, often in a fair condition of preservation, is to be found in various parish churches about the country. The schemes of Henry III were vast; extensive wall decorations were carried out for him at Winchester, Nottingham, Guildford and Dublin, but the greatest splendour was lavished upon the newly built Abbey and Palace of Westminster.

Westminster was therefore the most important artistic centre in the thirteenth century apart from St. Albans. At the head of the Westminster workshop was a monk referred to in the rolls as the 'King's Beloved Painter Master William.' He is first heard of in 1240 as working at Winchester, so that it is probable that his work for the king combined some of the older traditions with those French tendencies which Henry's influence introduced. It was Master William who decorated The Painted Chamber in Westminster Palace, but his

37

work was destroyed in the fire of 1262, and the repainting that occurred soon after may not have been by his own hand. This later work was rediscovered early in the year 1800, only to be destroyed again in the fire of 1834.

In St. George's Chapel, Windsor, however there is a fragment of a painting which is believed to be the work of Master William. It represents the head of a king with staring eyes, and is carried out with fluent ease.

A more complete painting attributed by some to this artist is in the Chapel of St. Faith in Westminster Abbey - a vaulted building never reached by daylight. St. Faith herself is painted on the eastern wall, a tall crowned standing figure with eyes mystically aflame, in a crimson cloak and underdress of green within a shrine of green and gold against a background of scarlet. In its architectural setting, the figure spreads an atmosphere of almost fanatical belief. Below St. Faith is painted a small Crucifixion and in the left hand corner a kneeling monk.

The spreading of French influence in Henry's reign can be seen in many illuminations, which are contemporary in date with those of the school of St. Albans. These tendencies came about largely because of the strong interest that the king took in the art of France, ever since he had visited La Sainte Chapelle in Paris in his youth and had declared his desire to take it home in a cart. It is fitting that Henry III and his daughter-in-law, Eleanor of Castile, should be remembered by two of the most beautiful tombs in Westminster Abbey. With the old king's death in 1272 ended an eventful epoch in English painting.

Mid-Gothic painting

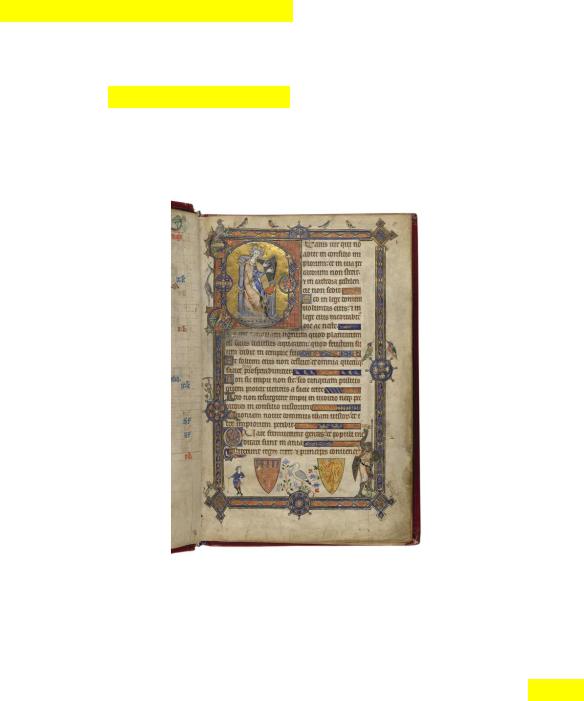

After the accession of Edward I, the styles of illumination in England and France, save for an occasional caricature in English work, became almost indistinguishable. Delicate minuteness was now the illuminator's chief aim, the demand being for Bibles on a small scale. Among rich patrons a fashion began for Psalters, which gave scope in the elaborate borders to their pages for purely secular and romantic subjects.

A good example is the Tenison Psalter which was begun in 1284 for Alphonso, son of Edward I, in honour of his proposed marriage with Margaret, daughter of the Count of Holland. In the first page of the text the shields of England and Holland appear in the lower margin, the seagull between them probably symbolizing the dividing sea. Alphonso died and never married Margaret, but luckily the first eleven pages of the Psalter were completed first. The illuminator, who was English and may have belonged to Grayfriars, Westminster, was clearly a close observer of birds, for the same page contains nine in all; among them are a thrush, a pigeon, a crane, an owl, a woodpecker and a kingfisher, each firmly and accurately drawn on a minute scale; their colouring is equally true, the pigeon's head being even gradated from green to purple.

The human beings are more conventional; David playing upon the harp with tapering fingers inside the initial B is a person of super-refinement. He

38

appears again as a youth in the lower margin, hurling a stone at Goliath, the large knight in the opposite corner. Goliath's pose, though awkward, has more appearance than that of any of the other figures of having been remembered from life. Beautiful as the finish of each detail is, the balance of the page as a whole is an even greater indication of the painter's genius. The bulky Goliath actually touching the last H of the text is needed to weigh against the large B diagonally opposite. There is sufficient symmetry and sufficient freedom in all the planning and spacing.

The colour scheme is also harmonious, silver occurring as well as gold, without for once having tarnished; a dark ultramarine being repeatedly contrasted with a subdued vermilion, while there are touches here and there of orange and of bright green; David's cloak is crimson and his harp is citronyellow. The elaboration of the ornament has much in common with that in contemporary 'Decorated' architecture.

The other pages of the Tenison Psalter are more freely planned; the border designs often springing from the long sweeping curve of a stalk or a leaf or even of a dragon's tail, from which the foliage sprouts. These also support little figures, human, animal or mythical.

http://www.thata.net/alphonsopsalter.JPG

King David playing the harp

This device, which was borrowed from earlier French illuminations reappears in English books of the early fourteenth century. The most important of these are the Psalters of East Anglia, the best of which were produced for a short period between about 1310 and 1330 for families in the wealthy diocese of Norwich. Their style, though also founded on that of French illuminations, has

39

developed an English vigour, clearly to be contrasted with the more delicately graceful contemporary work in France.

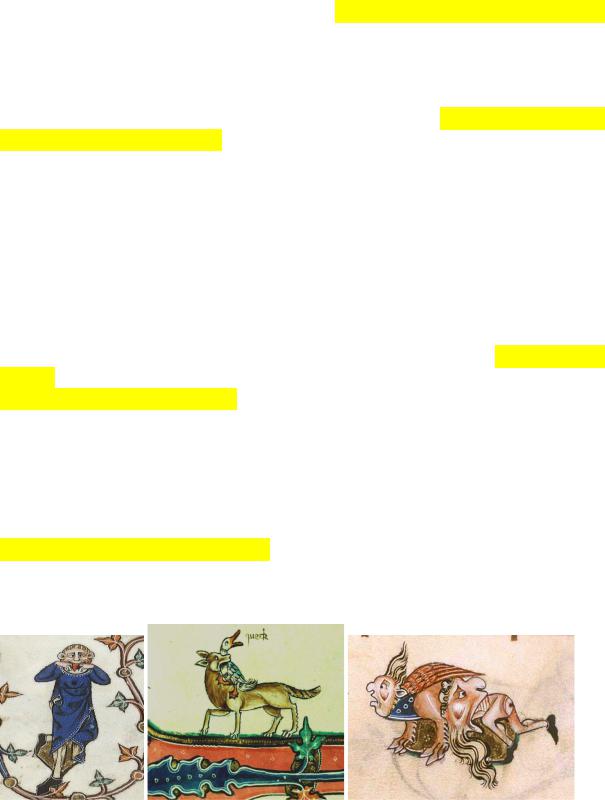

The pages of these East Anglian Psalters usually have a wide border, often decorated with heraldic devices, and with figures and animals boldly and firmly drawn. Sometimes the illuminator is an exquisite draughtsman of lowers as in the Ormesby Psalter (1320-1330) where the borders blossom forth into cornflowers, sweet peas, pinks and acorns. With such patterns are frequently combined grotesque subjects; in one border of the Ormesby Psalter, two naked men, mounted respectively upon a lion and a wild boar, are having a fight; their proportions may be inaccurate, but the drawing shows a surprising grasp of solidity and even of anatomy.

The Gorleston Psalter mentions, in the calendar for March 8, the dedication of Gorleston Church, Suffolk; it was probably at Gorleston that the Psalter was carried out between 1322 and 1324. The frontispiece consists of a particularly elaborate design of the Tree of Jesse. But the greatest charm of the book lies in the humorous subjects in the borders of other pages; in one, a cat dressed as a bishop is preaching to some ducks; in another, one grotesque figure is playing upon a bagpipe to annoy another; in a third instance, some rabbits are seen conducting a funeral a subject, which has clearly been conceived as a caricature of the priestly processions, which the artist must many times have witnessed. The delightful invention has resulted in a pattern of quite unforced beauty. Only the rabbit sitting upon the bier and blowing the trumpet can be said to offend the strictest decorum; the others are most ceremonious; the foremost with the bells looks back to see why the procession has stopped; the cross-bearer and candle-bearers stand at attention, too well trained to look round; the two priests who are the essence of dignity, one portly with an aspergillum for sprinkling holy water, the other slimmer with a thurible, are looking back to give orders to the dogs, who are collapsing under the weight of the coffin. The drawing may not be faultlessly accurate, but shows the draughtsman to have had a lively and appreciative memory. The colour is partly imaginary and partly naturalistic; the rabbits are the true fawn colour, but the dogs are a bright orange which occurs again in touches on the surplices; the pattern on the pall is dull pink and white; the cross alone being gold.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Gorleston2.JPG

40