03

.pdfSociolinguistics also teaches that power relationships are reflected in vocabulary changes. In all the cases of pejoration that were mentioned above, such as boor, churl, villain, etc., it was the ruling class that imposed evaluation. The opposite is rarely the case. One example deserves attention though: sir + -ly used to mean ‘masterful 1 and now surly means ‘rude in

abad-tempered way’.

D. Leith devotes a special paragraph in his “Social History of English” to the semantic disparagement of women. He thinks that power relationships in English are not confined to class stratification, that male domination is reflected in the history of English vocabulary, in the ways in which women are talked about. There is a rich vocabulary of affective words denigrating women, who do not conform to the male ideal. A few examples may be mentioned. Hussy is a reduction of ME huswif (housewife), it means now ‘a woman of low morals’ or ‘a bold saucy girl’; doll is not only a toy but is also used about a kept mistress or about a pretty and silly woman; wench formerly referred to a female child, later a girl of the rustic or working class and then acquired derogatory connotations.

Within the diachronic approach the phenomenon of e u p h e m i s m

(Gr euphemismos < eu ‘good’ and pheme ‘voice’) has been repeatedly classed by many linguists as t a b о о , i.e. a prohibition meant as a safeguard against supernatural forces. This standpoint is hardly acceptable for modern European languages. St. Ullmann returns to the conception of taboo several times illustrating it with propitiatory names given in the early periods of language development to such objects of superstitious fear as the bear and the weasel. He proves his point by observing the same phenomenon, i.e. the circumlocution used to name these animals, in other languages. This is of historical interest, but no similar opposition between a direct and a propitiatory name for an animal, no matter how dangerous, can be found in present-day English.

With peoples of developed culture and civilisation euphemism is intrinsically different, it is dictated by social usage, etiquette, advertising, tact, diplomatic considerations and political propaganda.

From the semasiological point of view euphemism is important, because meanings with unpleasant connotations appear in words formerly neutral as a result of their repeated use instead of words that are for some reason unmentionable, c f . deceased ‘dead’, deranged ‘mad’.

Much useful material on the political and cultural causes of coining euphemisms is given in “The Second Barnhart Diction ary of New English”. We read there that in modern times euphemisms became important devices in political and military propaganda. Aggressive attacks by armadas of bombers which most speakers of English would call air raids are officially called protective reaction, although there is nothing protective or defensive about it. The CIA agents in the United States often use the word destabilise for all sorts of despicable or malicious acts and subversions designed to cause to topple an established foreign government or to falsify an electoral campaign. Shameful secrets of various underhand CIA operations, assassinations, interception of mail, that might, if revealed, embarrass the government, are called family jewels.

75

http://angli4anka.at.ua

It is decidedly less emotional to call countries with a low standard of living underdeveloped, but it seemed more tactful to call them developing. The latest terms (in the 70s) are L.D.C. — less developed countries and

M.D.C. — more developed countries, or Third World countries or emerging countries if they are newly independent.

Other euphemisms are dictated by a wish to give more dignity to a profession. Some barbers called themselves hair stylists and even hairologists, airline stewards and stewardesses become flight attendants, maids become house workers, foremen become supervisors, etc.

Euphemisms may be dictated by publicity needs, hence ready-tailored and ready-to-wear clothes instead of ready-made. The influence of massadvertising on language is growing, it is felt in every level of the language.

Innovations possible in advertising are of many different types as G.N. Leech has shown, from whose book on advertising English the following example is taken. A kind of orange juice, for instance, is called Tango. The justification of the name is given in the advertising text as follows: “ Get this different tasting Sparkling Tango. Tell you why: made from whole oranges. Taste those oranges. Taste the tang in Tango. Tingling tang, bubbles — sparks. You drink it straight. Goes down great. Taste the tang in Tango. New Sparkling Tango”. The reader will see for himself how many expressive connotations and rhythmic associations are introduced by the salesman in this commercial name in an effort to attract the buyer’s attention. If we now turn to the history of the language, we see economic causes are obviously at work in the semantic development of the word wealth. It first meant ‘well-being’, ‘happiness’ from weal from OE wela whence well. This original meaning is preserved in the compounds commonwealth and commonweal. The present meaning became possible due to the role played by money both in feudal and bourgeois society. The chief wealth of the early inhabitants of Europe being the cattle, OE feoh means both ‘cattle’ and ‘money’, likewise Goth faihu; Lat pecus meant ‘cattle’ and pecunia meant ‘money’. ME fee-house is both a cattle-shed and a treasury. The present-day English fee most frequently means the price paid for services to a lawyer or a physician. It appears to develop jointly from the above mentioned OE feoh and the Anglo-French fee, fie, probably of the same origin, meaning ‘a recompense’ and ‘a feudal tenure’. This modern mean ing is obvious in the following example: Physicians of the utmost fame were called at once, but when they came they answered as they took their fees, “There is no cure for this disease.” (Belloc)

The constant development of industry, agriculture, trade and transport bring into being new objects and new notions. Words to name them are either borrowed or created from material already existing in the language and it often happens that new meanings are thus acquired by old words.

http://angli4anka.at.ua

Chapter 5

MORPHOLOGICAL STRUCTURE OF ENGLISH WORDS.

AFFIXATION

§ 5.1 MORPHEMES. FREE AND BOUND FORMS. MORPHOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION OF WORDS. WORD-FAMILIES

If we describe a wоrd as an autonomous unit of language in which a particular meaning is associated with a particular sound complex and which is capable of a particular grammatical employment and able to form a sentence by itself (see p. 9), we have the possibility to distinguish it from the other fundamental language unit, namely, the morpheme.

A m o r p h e m e i s also an association of a given meaning with a given sound pattern. But unlike a word it is not autonomous. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words, not independently, although a word may consist of a single morpheme. Nor are they divisible into smaller meaningful units. That is why the morpheme may be defined as the minimum meaningful language unit.

The term m o r p h e m e is derived from Gr morphe ‘form’ + -eme. The Greek suffix -erne has been adopted by linguists to denote the smallest significant or d i s t i n c t i v e u n i t . (Cf. phoneme, sememe.) The morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of form. A form in these cases is a recurring discrete unit of speech.

A form is said to be free if it may stand alone without changing its meaning; if not, it is a b o u n d form, so called because it is always bound to something else. For example, if we compare the words sportive and elegant and their parts, we see that sport, sportive, elegant may occur alone as utterances, whereas eleg-, -ive, -ant are bound forms because they never occur alone. A word is, by L. Bloomfield’s definition, a minimum free form. A morpheme is said to be either bound or free. This statement should bе taken with caution. It means that some morphemes are capable of forming words without adding other morphemes: that is, they are homonymous to free forms.

According to the role they play in constructing words, morphemes are

subdivided into r o o t s |

and a f f i x e s . The latter are further subdi- |

|||

vided, according to their position, |

into p r e f i x e s , |

s u f f i x e s |

||

and i n f i x e s , and |

according |

to their function and |

meaning, |

into |

d e r i v a t i o n a l and f u n c t i o n a l . a f f i x e s , the |

latter |

|||

also called e n d i n g s |

or o u t e r |

f o r m a t i v e s. |

|

|

When a derivational or functional affix is stripped from the word, what remains is a s t e m (or astern b a s e ) . The stem

77

http://angli4anka.at.ua

expresses the lexical and the part of speech meaning. For the word hearty and for the paradigm heart (sing.) — hearts (pi.)1 the stem may be represented as heart-. This stem is a single morpheme, it contains nothing but the root, so it is a s i m p l e s t e m . It is also a f r e e s t e m because it is homonymous to the word heart.

A stem may also be defined as the part of the word that remains unchanged throughout its paradigm. The stem of the paradigm hearty — heartier — (the) heartiest is hearty-. It is a free stem, but as it consists of a root morpheme and an affix, it is not simple but derived. Thus, a stem containing one or more affixes i s a d e r i v e d s t e m . If after deducing the affix the remaining stem is not homonymous to a separate word of the same root, we call it a b o u n d s t e m . Thus, in the word cordial ‘proceeding as if from the heart’, the adjective-forming suffix can be separated on the analogy with such words as bronchial, radial, social. The remaining stem, however, cannot form a separate word by itself, it is bound. In cordially and cordiality, on the other hand, the derived stems are free.

Bound stems are especially characteristic of loan words. The point may be illustrated by the following French borrowings: arrogance, charity, courage, coward, distort, involve, notion, legible and tolerable, to give but a few.2 After the affixes of these words are taken away the remaining elements are: arrog-, char-, cour-, cow-, -tort, -volve, not-, leg-, toler-, which do not coincide with any semantically related independent words.

Roots are main morphemic vehicles of a given idea in a given language at a given stage of its development. A root may be also regarded as the ultimate constituent element which remains after the removal of all functional and derivational affixes and does not admit any further analysis. It is the common element of words within a w o r d - f a m i l y . Thus, -heart- is the common root of the following series of words: heart, hearten, dishearten, heartily, heartless, hearty, heartiness, sweetheart, heart-broken, kind-hearted, whole-heartedly, etc. In some of these, as, for example, in hearten, there is only one root; in others the root -heart is combined with some other root, thus forming a compound like sweetheart.

The root word heart is unsegmentable, it is non-motivated morphologically. The morphemic structure of all the other words in this word-family is obvious — they are segmentable as consisting of at least two distinct morphemes. They may be further subdivided into: 1) those formed by affixation o r a f f i x a t i o n a l d e r i v a t i v e s consisting of a root morpheme and one or more affixes: hearten, dishearten, heartily, heartless, hearty, heartiness; 2) c o m p o u n d s , in which two, or very rarely more, stems simple or derived are combined into a lexical unit: s w e e t h e a r t ,

h e a r t - s h a p e d , |

h e a r t - b r o k e n o r 3 ) d e r i v a t i o n a l |

c o m p o u n d s |

where words of a phrase are joined together by composi- |

tion and affixation: kind-hearted. This last process is also called phrasal derivation ((kind heart) + -ed)).

1A paradigm is defined here as the system of grammatical forms characteristic of a word. See also p. 23.

2Historical lexicology shows how sometimes the stem becomes bound due to the internal changes in the stem that accompany the addition of affixes; сf. broad : : breadth, clean : : cleanly ['klenli], dear : : dearth [dэ:θ], grief : : grievous.

78

http://angli4anka.at.ua

There exist word-families with several tmsegmentable members, the derived elements being formed by conversion or clipping. The word-family with the noun father as its centre contains alongside affixational derivatives fatherhood, fatherless, fatherly a verb father ‘to adopt’ or ‘to originate’ formed by conversion.

We shall now present the different types of morphemes starting with the root.

It will at once be noticed that the root in English is very often homonymous with the word. This fact is of fundamental importance as it is one of the most specific features of the English language arising from its general grammatical system on the one hand, and from its phonemic system on the other. The influence of the analytical structure of the language is obvious. The second point, however, calls for some explanation. Actually the usual phonemic shape most favoured in English is one single stressed syllable: bear, find, jump, land, man, sing, etc. This does not give much space for a second morpheme to add classifying lexico-grammatical meaning to the lexical meaning already present in the root-stem, so the lexico-grammatical meaning must be signalled by distribution.

In the phrases a morning’s drive, a morning’s ride, a morning’s wa lk the words drive, ride and walk receive the lexico-grammatical meaning of a noun not due to the structure of their stems, but because they are preceded by a genitive.

An English word does not necessarily contain formatives indicating to what part of speech it belongs. This holds true even with respect to inflectable parts of speech, i.e. nouns, verbs, adjectives. Not all roots are free forms, but p r o d u c t i v e r o o t s , i.e. roots capable of producing new words, usually are. The semantic realisation of an English word is therefore very specific. Its dependence on context is further enhanced by the widespread occurrence of homonymy both among root morphemes and affixes. Note how many words in the following statement might be ambiguous if taken in isolation: A change of work is as good as a rest.

The above treatment of the root is purely synchronic, as we have taken into consideration only the facts of present-day English. But the same problem of the morpheme serving as the main signal of a given lexical meaning is studied in e t y m o l o g y . Thus, when approached historically or diachronically the word heart will be classified as Common Germanic. One will look for c o g n a t e s , i.e. words descended from a common ancestor. The cognates of heart are the Latin cor, whence cordial ‘hearty’, ‘sincere’, and so cordially and cordiality, also the Greek kardia, whence English cardiac condition. The cognates outside the English vocabulary are the Russian cepдце, the German Herz, the Spanish corazon and other words.

To emphasise the difference between the synchronic and the diachronic treatment, we shall call the common element of cognate words in different languages not their root but their r a d i c a l element.

79

http://angli4anka.at.ua

These two types of approach, synchronic and diachronic, give rise to two different principles of arranging morphologically related words into groups. In the first case series of words with a common root morpheme in which derivatives are opposable to their unsuffixed and unprefixed bases, are combined, сf. heart, hearty, etc. The second grouping results in families of historically cognate words, сf. heart, cor (Lat), Herz (Germ), etc.

Unlike roots, affixes are always bound forms. The difference between suffixes and prefixes, it will be remembered, is not confined to their respective position, suffixes being “fixed after” and pre fixes “fixed before” the stem. It also concerns their function and meaning.

A s u f f i x is a derivational morpheme following the stem and forming a new derivative in a different part of speech or a different word class,

сf. -en, -y, -less in hearten, hearty, heartless. When both the underlying and the resultant forms belong to the same part of speech, the suffix serves to differentiate between lexico-grammatical classes by rendering some very general lexico-grammatical meaning. For instance, both -ify and -er are verb suffixes, but the first characterises causative verbs, such as horrify, purify, rarefy, simplify, whereas the second is mostly typical of frequentative verbs: flicker, shimmer, twitter and the like.

If we realise that suffixes render the most general semantic component of the word’s lexical meaning by marking the general class of phenomena to which the referent of the word belongs, the reason why suffixes are as a rule semantically fused with the stem stands explained.

A p r e f i x is a derivational morpheme standing before the root and modifying meaning, c f . hearten — dishearten. It is only with verbs and statives that a prefix may serve to distinguish one part of speech from another, like in earth n — unearth v, sleep n — asleep (stative).

It is interesting that as a prefix en- may carry the same meaning of being or bringing into a certain state as the suffix -en, сf. enable, encamp, endanger, endear, enslave and fasten, darken, deepen, lengthen, strengthen.

Preceding a verb stem, some prefixes express the difference between a transitive and an intransitive verb: stay v and outstay (sb) vt. With a few exceptions prefixes modify the stem for time (pre-, post-), place (in-, ad-) or negation (un-, dis-) and remain semantically rather independent of the stem.

An i n f i x is an affix placed within the word, like -n- in stand. The type is not productive.

An affix should not be confused with a c o m b i n i n g f o r m . A combining form is also a bound form but it can be distinguished from an affix historically by the fact that it is always borrowed from another language, namely, from Latin or Greek, in which it existed as a free form, i.e. a separate word, or also as a combining form. They differ from all other borrowings in that they occur in compounds and derivatives that did not exist in their original language but were formed only in modern times in English, Russian, French, etc., сf. polyclinic, polymer; stereophonic, stereoscopic, telemechanics, television. Combining forms are mostly international. Descriptively a combining form differs from an affix, because it can occur as one constituent of a form whose only other constituent is an affix, as in graphic, cyclic.

80

http://angli4anka.at.ua

Also affixes are characterised either by preposition with respect to the root (prefixes) or by postposition (suffixes), whereas the same combining form may occur in both positions. Cf. phonograph, phonology and telephone, microphone, etc.

§ 5.2 AIMS AND PRINCIPLES OF MORPHEMIC AND WORD-FORMATION ANALYSIS

A synchronic description of the English vocabulary deals with its pre- sent-day system and its patterns of word-formation by comparing words simultaneously existing in it.1

If the analysis is limited to stating the number and type of morphemes that make up the word, it is referred to as m o r p h e m i c . For instance, the word girlishness may be analysed into three morphemes: the root -girl- and two suffixes -ish and -ness. The morphemic classification of words is as follows: one root morpheme — a root wor d (girl), one root morpheme plus one or more affixes — a derived word (girlish, girlishness), two or more stems — a compound word (girl-friend), two or more stems and a common affix — a compound derivative (old-maidish). The morphemic analysis establishes only the ultimate constituents that make up

the word (see p. 85). |

|

|

A structural word-formation analysis proceeds |

further: it studies |

the |

s t r u c t u r a l c o r r e l a t i o n with other |

words, the structural |

|

patterns or rules on which words are built. |

|

|

This is done with the help of the principle of o p p o s i t i o n s |

(see |

|

p. 25), i.e. by studying the partly similar elements, the difference between which is functionally relevant; in our case this difference is sufficient to create a new word. Girl and girlish are members of a morphemic opposition. They are similar as the root morpheme -girl- is the same. Their distinctive feature is the suffix -ish. Due to this suffix the second member of the opposition is a different word belonging to a different part of speech. This binary opposition comprises two elements.

А с о r r e l a t i о n is a set of binary oppositions. It is composed of two subsets formed by the first and the second elements of each couple, i.e. opposition. Each element of the first set is coupled with exactly one element of the second set and vice versa. Each second element may be derived from the corresponding first element by a general rule valid for all members of the relation (see p. 26). Observing the proportional opposition:

girl |

child |

woman |

monkey |

spinster |

book |

girlish |

childish |

womanish |

monkeyish |

spinsterish |

bookish |

1 The contribution of Soviet scholars to this problem is seen in the works by M.D. Stepanova, S.S. Khidekel, E.S. Koubryakova, T.M. Belyaeva, O.D. Meshkov, P.A. Soboleva and many other authors.

6 И. В. Арнольд |

81 |

http://angli4anka.at.ua

it is possible to conclude that there is in English a type of derived adjectives consisting of a noun stem and the suffix -ish. Observation also shows that the stems are mostly those of animate nouns, and permits us to define the relationship between the structural pattern of the word and its meaning. Any one word built according to this pattern contains a semantic component common to the whole group, namely: ‘typical of, or having the bad qualities of. There are also some other uses of the adjective forming ‘ish, but they do

not concern us here. |

|

|

In the above |

example the results of |

morphemic analysis and the |

s t r u c t u r a l |

w o r d - f o r m a t i o n |

a n a l y s i s practically coin- |

cide. There are other cases, however, where they are of necessity separated. The morphemic analysis is, for instance, insufficient in showing the difference between the structure of inconvenience v and impatience n; it classifies both as derivatives. From the point of view of word-formation pattern, however, they are fundamentally different. It is only the second that is formed by derivation. Compare:

impatience n = patience n = corpulence n impatient a patient a corpulent a

The correlation that can be established for the verb inconvenience is different, namely:

inconvenience v = pain v = disgust v = anger v = daydream v inconvenience n pain n disgust n anger n daydream n

Here nouns denoting some feeling or state are correlated with verbs causing this feeling or state, there being no difference in stems between the members of each separate opposition. Whether different pairs in the correlation are structured similarly or differently is irrelevant. Some of them are simple root words, others are derivatives or compounds. In terms of wordformation we state that the verb inconvenience when compared with the noun inconvenience shows relationships characteristic of the process of conversion. Cf. to position where the suffix -tion does not classify this word as an abstract noun but shows it is derived from one.

This approach also affords a possibility to distinguish between compound words formed by composition and those formed by other processes. The words honeymoon n and honeymoon v are both compounds, containing two free stems, yet the first is formed by composition: honey n + moon n > honeymoon n, and the second by conversion: honeymoon n> honeymoon v (see Ch. 8). The treatment remains synchronic because it is not the origin of the word that is established but its present correlations in the vocabulary and the patterns productive in present-day English, although sometimes it is difficult to say which is the derived form.

The analysis into immediate constituents described below permits us to obtain the morphemic structure and provides the basis for further wordformation analysis.

82

http://angli4anka.at.ua

§ 5.3 ANALYSIS INTO IMMEDIATE CONSTITUENTS

A synctironic morphological analysis is most effectively accomplished by the procedure known as the analysis into i m m e d i a t e c o n - s t i t u e n t s (IC’s). Immediate constituents are any of the two meaningful parts forming a larger linguistic unity. First suggested by L. Bloomfield1 it was later developed by many linguists.2 The main opposition dealt with is the opposition of stem and affix. It is a kind of segmentation revealing not the history of the word but its m o t i v a t i o n , i.e. the data the listener has to go by in understanding it. It goes without saying that unmotivated words and words with faded motivation have to be remembered and understood as separate signs, not as combinations of other signs.

The method is based on the fact that a word characterised by morphological divisibility (analysable into morphemes) is involved in certain structural correlations. This means that, as Z. Harris puts it, “the morpheme boundaries in an utterance are determined not on the basis of considerations interior to the utterance but on the basis of comparison with other utterances. The comparisons are controlled, i.e. we do not merely scan various random utterances but seek utterances which differ from our original one only in stated portions. The final test is in utterances which are only minimally different from ours."3

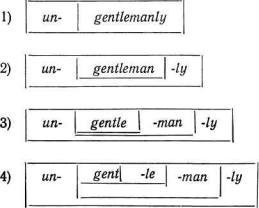

A sample analysis which has become almost classical, being repeated many times by many authors, is L. Bloomfield’s analysis of the word ungentlemanly. As the word is convenient we take the same example. Comparing this word with other utterances the listener recognises the morpheme -un- as a negative prefix because he has often come across words built on the pattern un- + adjective stem: uncertain, unconscious, uneasy, unfortunate, unmistakable, unnatural. Some of the cases resembled the word even more closely; these were: unearthly, unsightly, untimely, unwomanly and the like. One can also come across the adjective gentlemanly. Thus, at the first cut we obtain the following immediate constituents: un- + gentlemanly. If we continue our analysis, we see that although gent occurs as a free form in low colloquial usage, no such word as lemanly may be found either as a free or as a bound constituent, so this time we have to separate the final morpheme. We are justified in so doing as there are many adjectives following the pattern noun stem + -ly, such as womanly, masterly, scholarly, soldierly with the same semantic relationship of ‘having the quality of the person denoted by the stem’; we also have come across the noun gentleman in other utterances. The two first stages of analysis resulted in separating a free and a bound form: 1) un~ + gentlemanly, 2) gentleman + -ly. The third cut has its peculiarities. The division into gent-+-lemon is obviously impossible as no such patterns exist in English, so the cut is gentle- + -man. A similar pattern is observed in nobleman, and so we state adjective stem

1Bloomfield L. Language. London, 1935. P. 210.

2See: Nida E. Morphology. The Descriptive Analysis of Words. Ann Arbor, 1946.

P. 81.

3Harris Z.S. Methods in Structural Linguistics. Chicago, 1952. P. 163.

6* |

83 |

http://angli4anka.at.ua

+ man. Now, the element man may be differently classified a s a s e m i - a f f i x (see § 6.2.2) or as a variant of the free form man. The word gentle is open to discussion. It is obviously divisible from the etymological viewpoint: gentle < (O)Fr gentil < Lat gentilis permits to discern the root or rather the radical element gent- and the suffix -il. But since we are only concerned with synchronic analysis this division is not relevant.

If, however, we compare the adjective gentle with such adjectives as brittle, fertile, fickle, juvenile, little, noble, subtle and some more containing the suffix -lei-He added to a bound stem, they form a pattern for our case. The bound stem that remains is present in the following group: gentle, gently, gentleness, genteel, gentile, gentry, etc.

One might observe that our procedure of looking for similar utterances has shown that the English vocabulary contains the vulgar word gent that has been mentioned above, meaning ‘a person pretending to the status of a gentleman' or simply'man’, but then there is no such structure as noun stem + -le, so the word gent should be interpreted as a shortening of gentleman and a homonym of the bound stem in question.

To sum up: as we break the word we obtain at any level only two IC’s, one of which is the stem of the given word. All the time the analysis is based on the patterns characteristic of the English vocabulary. As a pattern showing the interdependence of all the constituents segregated at various stages we obtain the following formula:

un- + {[{gent- + -le) + -man] + -ly}

Breaking a word into its immediate constituents we observe in each cut the structural order of the constituents (which may differ from their actual sequence). Furthermore we shall obtain only two constituents at each cut, the ultimate constituents, however, can be arranged according to their sequence in the word: un-+gent-+-le+-man+'ly.

A box-like diagram presenting the four cuts described looks as follows:

84

http://angli4anka.at.ua