01 POWER ISLAND / 01 CCPP / DOE_Global LNG Fundamentals_15.03.18

.pdf

DOMESTIC MARKET

Market Structure

The ability of local or regional gas and power markets to partially or wholly underpin a major gas resource development depends largely on the way in which the wholesale and retail gas and power markets are structured.

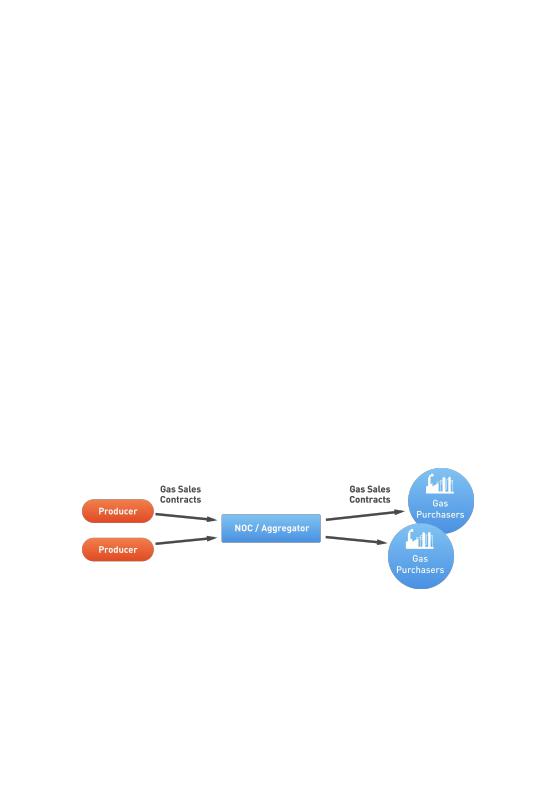

The market segments for natural gas are supply, wholesale, and retail. Each market segment can be structured as exclusive, mixed, or competitive, with prices either regulated or market-based. In the supply segment, the producer sells to an aggregator or directly to an end-user. In the wholesale segment, an entity, such as an aggregator, purchases gas from another entity for resale to other customers. In the retail segment, an end-user purchases gas from an entity for its own use.

An example of an exclusive structure is shown below. A gas aggregator, for example the national oil or gas company, acquires natural gas, provides transportation and compression, if required, and then on-sells the natural gas to wholesale and retail customers.

Of critical importance in any energy market, is a clear and dependable path through which end-users pay for energy received. The flow of energy from the gas developer through to the end-user and the flow of funds in the opposite direction are the key feature of any market and the critical

35

DOMESTIC MARKET

facilitating feature of any project. For domestic and regional markets to provide dependable revenues similar to that which would result from gas or LNG exports to international markets, appropriate planning and execution of market rules, and the nature and level of regulation, are critical factors.

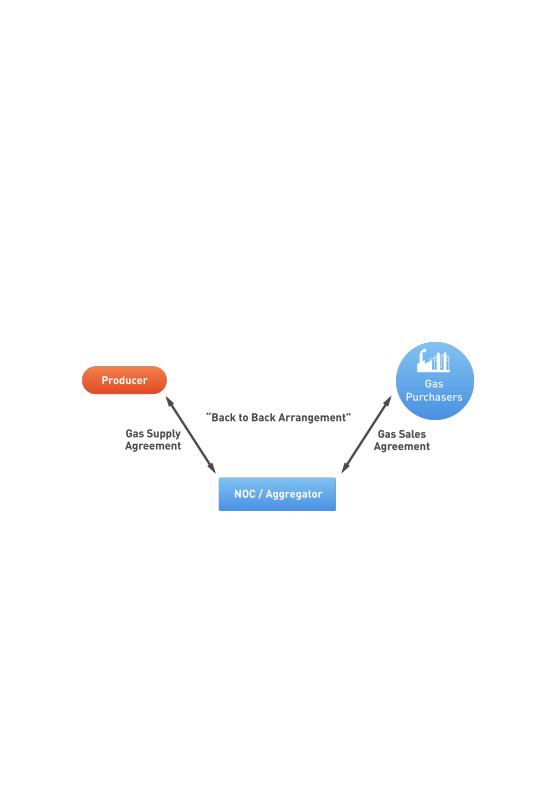

One of the concerns with an aggregator exclusive structure is that the aggregator will stand between the supplier and the customer for contractual and payment purposes. This could lead to a situation where the aggregator is obligated to pay the supplier despite the fact that the gas customer has not paid the aggregator. This concern can be addressed through a mixed structure that includes some sort of payment security from customers or security provided on behalf of the customers.

The diagram below shows an example of a back-to-back structure where the supplier looks to the customers for payment instead of the aggregator:

36

DOMESTIC MARKET

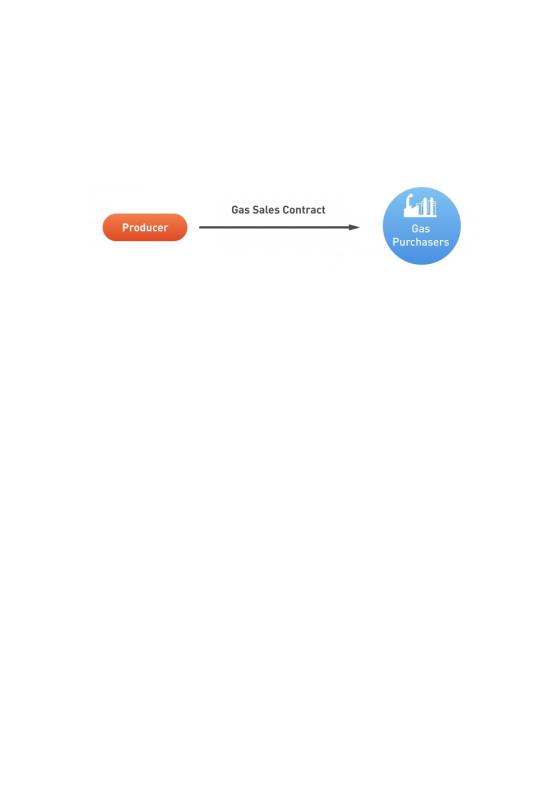

In a more established market, as shown below, a direct commercial structure where a supplier sells directly to a customer may be used. This structure requires that the supplier or the customer obtains transportation for the gas supply.

In the case of an export sale, the project developers usually rely on a longterm take-or-pay LNG contract, supported by a creditworthy buyer who will

sign a binding contract, thereby putting a strong balance sheet behind the purchase obligations. This means that project developers and lenders

rarely need to examine what happens to the gas once the take-or-pay buyer has purchased it, so the need to examine market rules downstream of the foundation sale-and-purchase agreement is rarely considered.

For emerging local and regional markets, establishing a creditworthy buyer presents more complex challenges, due to the lack of gas buyers with a pre-existing credit position who are able to support financing requirements. As a result, lenders and project developers typically have to examine the gas or electricity value chain down to the source of the cash flow, which terminates at the end-user of the gas or power produced. In order to provide a similar level of credit support as a traditional take-or-pay contract, full understanding of the way in which monies flow through the various market participants is integral to ensuring the market is structured to support the project.

37

DOMESTIC MARKET

Elements of a Gas Master Plan

A starting point for many countries, especially countries that wish to develop gas resources and/or domestic markets for natural gas, is the creation of a Gas Master Plan (GMP). While the contents of a GMP will be unique to each country, there are some helpful general guidelines and principles. In general, a GMP is a holistic framework to identify and evaluate options for natural gas use for domestic supply and/or export. The main goal of the GMP is to provide the foundation to guide policy development for the gas sector of the country. The GMP provides a detailed road map for taking strategic, political and institutional decisions, on the basis of which, investments can be planned and implemented in a coordinated manner.

The role of the government in developing the GMP is to provide a stable, transparent regulatory, fiscal, and financial policy regime to foster the development of the gas sector in a manner which benefits the country as a whole.

While the elements of the GMP vary by the country, there are some broad elements to consider. These elements include:

>Objective of the Gas Master Plan

>Gas resource evaluation

>Gas utilization strategy and options consistent with country's energy policy

>Domestic supply and demand analysis (power and non-power sector)

>Identification of other domestic “priority” projects

>Infrastructure development plan/formulation

>Institutional, regulatory and fiscal framework

38

DOMESTIC MARKET

>Development of recommendations about the volumes and revenues from gas finds and future gas production

>Identification of possible mega or “anchor” projects. For example, a country with a large natural gas find might consider an LNG export project, or other similar industrial-scale plant such as methanol, ammonia production, gas-to-liquids (GTL) projects and dimethyl ether (DME).

>Formulation of a roadmap for implementation of projects

>Gas sector regulatory reforms

>Socioeconomic and environmental issues associated with development

>Gas pricing policy

An “anchor” project is a large project that provides the economies of scale that may justify the investments in capital-intensive gas infrastructure, which is then available to smaller users. Launching a gas industry from scratch has traditionally required one, or more, large “anchor” customers to undertake to purchase enough gas to justify the significant investments required to build the requisite pipeline infrastructure. Examples of anchor projects include LNG export terminals that may justify offshore gas exploration and production in the first place, power plants, gas-to-liquids plants, methanol or fertilizer plants, which in turn could provide the economic underpinning for pipeline expansions.

With the generally weak global demand for LNG from traditional markets such as Europe or Asia, GMP considerations may have to focus more closely on domestic or regional gas demand to underpin major gas developments, and this may require innovative approaches to gas market development, contractual mechanisms for gas sales, and financing arrangements.

Examples of Domestic Gas Projects

To replace flagging global demand for natural gas, the range of mega or anchor projects might also include a discussion of “priority” gas projects that might be undertaken while plans for any mega projects are being developed. Examples of possible projects include:

39

DOMESTIC MARKET

>Power projects

>Gas-to-liquids projects

>Fertilizer plans

>Petrochemicals

>Methanol projects

>Gas transmission and distribution pipelines

>Fuel for industry such as iron, steel and cement projects

Domestic Gas Reservations – Domestic Supply Obligation

Assurance of gas supply is critical to delivering the policy objectives of the GMP. This includes recognition that gas-based industries, such as methanol, fertilizer, or power industries, need a certainty of gas supply before large investments are made. At the same time, many governments face the issue of ensuring that gas is available for critical domestic gas utilization projects which will advance the domestic economic growth agenda.

To balance these often competing objectives, many gas-producing nations have some form of gas reservation policy or domestic supply obligation, aimed at ensuring that local industry and local consumers are not disadvantaged by gas exports.

International examples of domestic supply obligations (DSO) include:

>Nigeria requires all oil and gas operators to set aside a pre-determined minimum amount of gas for use in the domestic market. This is a regulatory obligation with the initial obligation level determined based on a review of the base-case demand scenario for gas in the domestic market. The domestic gas obligation provides a base load of gas that must be processed through the gas-gathering and processing facilities. Since the obligation to supply the domestic market is the responsibility of the gas supplier, title to gas-processed remains with the gas suppliers.

40

DOMESTIC MARKET

>Israel, Indonesia, and Egypt have laws mandating that a percentage of gas extracted must stay within their domestic markets. Israel reserves 60% of its offshore natural gas. Egypt has legislated that 30% of gas production must be directed to domestic consumers. Indonesian reservation is applied on a case-by-case basis to new projects, but reservations of up to 40% have been agreed to in recent years.

>In the United States, the Department of Energy’s (DOE) authority to regulate U.S. natural gas exports arises from the Natural Gas Act (NGA) of 1938, as amended. By law, applications to export U.S. natural gas to countries with which the United States has Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) are deemed to be consistent with the public interest and the Secretary of Energy must grant authorizations without modification or delay. The NGA directs DOE to evaluate applications to export U.S. natural gas to non-FTA countries. Under the NGA, DOE is required to grant applications for authorizations to export U.S. natural gas to non-FTA countries, unless the Department finds that the proposed exports will not be consistent with the public interest, or where trade is explicitly prohibited by law or policy. Canada also has similar public interest laws regarding the export of its gas.

>Norway, Qatar, Russia, Algeria, and Malaysia control domestic supply from their gas reserves by having state-owned companies taking the role of dominant producer.

>Western Australia is the only state in Australia with a gas reservation policy. Under Western Australia law, 15% of all the gas produced in that state must remain in the state. Western Australia’s gas reservation scheme has been able to guarantee domestic supply at attractive prices, while still allowing investment in the LNG industry and a healthy level of exports.

41

DOMESTIC MARKET

Gas Sector Regulatory Reforms

Depending on the level of development in the country, various regulatory reforms may be needed to promote the development of the gas sector. Legislation and regulations for licensing the construction, operations, and pricing of natural gas transmission and distribution pipelines might be needed. There should be standard, publicly available terms and conditions for licensing developers of infrastructure that define service obligations, operating rules, and tariffs.

The licensing, operations and tariffs of gas transmission and distribution pipelines should be overseen by an independent regulator.

Many governments are considering unbundling value chains for regulatory purposes. Unbundling refers to the separation of segments in the gas value chain to reduce the potential for monopoly, and to increase transparency and the ease of regulating smaller projects. Consumers should see the gas price separately from the cost of transporting and distributing it for transparency. Unbundling can facilitate third-party access to pipelines.

42

Structuring an

LNG Project

Introduction Choosing a Project Structure Driving Factors on Choice of Export Structure Import Project Structures

STRUCTURING AN LNG PROJECT

Introduction

Natural gas liquefaction projects require considerable capital investment and involve multiple project participants. As a result, the projects typically need to have long, productive lives and enduring partnerships. Risk needs to be allocated and functions for the project participants defined in order to allow debt to be paid off and to generate sufficient returns for investors. Each project would be expected to produce LNG over a period which could span 20-40 years, so it is important to structure the project correctly from its inception to anticipate project risks over time and to avoid misalignments between stakeholders and other risks to the project's success.

As a result of their high costs, LNG projects are typically executed by joint venture entities with more than one sponsor and with multiple project participants. An appropriate structure will enable entities, often with different aims, such as governments or state-owned entities and private sector companies to comfortably participate in the project. Private sector companies could be energy companies, utilities, and, as is increasingly the case, investors from the financial community. A well-structured project will afford participants sufficient protection in their endeavors. A robust and well-thought-out structure can make provisions for changes to ownership and the future addition of facilities. Liquefaction projects are often expanded via the addition of new LNG trains.

The structure of liquefaction projects will have ramifications for the allocation of risk. The structure can determine whether the sponsors are able to successfully sign sales or tolling contracts with buyers or tolling counterparties. It will also have an impact on whether the project is able to attract further equity investors, if needed, and raise debt funding from financiers. If a project's structure is weak or overly complicated, the sponsors may struggle to attract buyers for their product as buyers will be evaluating project risk when deciding whether to enter into a sales contract. The structure can impact the financing to the extent that the sponsors may

44