Экзамен зачет учебный год 2023 / Sparkes, A New Land Law

.pdf

30

PROTECTION OF DOMESTIC

BORROWERS

Domestic sector lenders. Unfair terms. Good lending practice. Instalment mortgages. Domestic repossession. Consumer credit agreements. Tenants. Oppression. Equitable misconduct: undue influence etc: infection; avoiding infection; legal advice; remedies. Nullity.

[30.01] Domestic borrowers are inevitably at a disadvantage against a commercial lender. This chapter explores lending controls, protection against repossession, oppression of borrowers, and undue influence and other forms of misconduct applied by borrowers to guarantors.

A. DOMESTIC SECTOR LENDERS

[30.02] From one point of view, domestic borrowers are simply consumers,1 though peculiarly vulnerable ones. Statutory control of lenders is provided by the consumer credit and building societies legislation – a patchwork which has not yet coalesced into an adequate protective shield.

1.Lenders

[30.03] Mutual building societies are regulated by statute.2 Most of their business should take the form of loans secured on land, that is a legal estate in a home made after adequate valuation.3 Insurance and other activities must be ring-fenced to prevent borrowers being pressured into buying associated products.4

Building societies, local authorities, many insurance companies and friendly societies, and charities are exempt from the control of the Consumer Credit Act 1974.5 Banks are controlled, along with the fringe lenders of the second mortgage market, all

1L Whitehouse “The Home-Owner: Citizen or Consumer?” ch 7 in Bright & Dewar; Grays’ Elements (3rd ed) ch 12.

2Building Societies Act 1986, as amended by LRA 2002 sch 11; HW Wilkinson [1985] Conv 1; A Samuels [1987] Conv 36; GA Morgan [1995] Conv 467.

3Building Societies Act 1997 part I, amending Building Societies Act 1986 part III.

4Building Societies Act 1986 ss 34–35; SI 2001/1826.

5Consumer Credit Act 1974 s 16; SI 1989/869 art 2, and regular amendments; there are minor exemptions.

DOMESTIC SECTOR LENDERS |

661 |

of which require a licence from the Director General of Fair Trading.6 Ombudsmen provide administrative redress for investors7 and building society borrowers,8 even against in-house valuations.9 There has been a deluge of complaints.

2.Advertising mortgages

[30.04] Consumer credit rules apply to all lenders (exempt or non-exempt) providing any level of credit to individuals. Advertisements must warn that:

“Your home is at risk if you do not keep up repayments on a mortgage or other loan secured on it.”10

Interest rates must be calculated in APR format which allows a comparison between different products, however imperfect. Other rules affect “hidden extras” such as endowment schemes, and the method of calculating the cost of borrowing.11 In National Westminster Bank v. Devon CC12 a mortgage provided for the interest rate to be fixed at a low rate for two years; the interest rate was advertised (legitimately) on the assumption that at the end of the fixed rate period the interest rate would remain the same for the rest of the term, even though an increase was inevitable in practice.

3.Mortgage Code

[30.05] A voluntary scheme to secure honesty, transparency, clarity and fairness in the advertisement of business is to be superseded in 2004 by much tougher controls under the Mortgage Code of the Financial Services Authority.13

4.Regulated consumer credit agreements

[30.06] Consumer credit agreements are used for buying fridges and cars, but some land mortgages may also fall within the statutory code,14 which does not mesh well with traditional mortgage law. This applies whenever “credit” is provided to an individual “debtor” – including individuals, couples, sole traders and business partners, but excluding companies. Regulated consumer credit agreements are those by

6Ss 21–41.

7R v. Investors Compensation Scheme ex p Bowden [1996] AC 261, HL. Building Societies Act 1997 s 32 provides for future amalgamation of various schemes.

8Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 ss 225–234, sch 17; A Samuels [1987] Conv 36; C Bell & JW Vaughan (1988) 132 SJ 1478; SE Edell [1989] Conv 253; R James & M Seneviratne [1992] CJQ 157; (1994) 23 Anglo-American 214.

9Halifax BS v. Edell [1992] Ch 436, Morritt J.

10Consumer Credit Act 1974 ss 43–54; numerous SIs state exemptions; Davies v. Directloans [1986] 1 WLR 823; First National Bank v. SS for Trade (1990) 154 JP 571, CA.

11SI 1989/596; Lombard Tricity Finance v. Paton [1989] 1 All ER 918, CA (variable rate acceptable);

Scarborough BS v. Humberside TSD [1997] CLYB 965.

12[1993] CCLR 69.

13Financial Services Authority document CP 146 (2002); see FSA website.

14JE Adams (1975) 39 Conv NS 94; A Rogerson (1975) 38 MLR 435; KE Lindgren (1977) 40 MLR 159; R Goode [1975] CLJ 79.

662 |

30. PROTECTION OF DOMESTIC BORROWERS |

non-exempt lenders where the loan does not exceed £25,000.15 The target is second loans to pay, for example, for home improvements, double glazing and holidays.16

Formalities are required for regulated consumer credit agreements, including an opportunity for withdrawal17 though this is not a requirement when a “restricted use credit agreement” is used to finance (or bridge) the purchase of a house. Regulated mortgages must follow a prescribed form, stating the total amount and rate of the charge for credit, and must be signed by both parties. Enforcement of a deformed mortgage was prohibited out of court and was discretionary in court18 – but it has been held that the lender’s human rights are infringed by this provision and a declaration of incompatibility has been made.19

B. UNFAIR TERMS

[30.07] The Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 has no application to mortgages of land,20 but a wider scope is allowed to the European-inspired Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999.21 This finer mesh has forced lenders to review and revise standard mortgage conditions to ensure compliance with the new regulations. Terms are potentially vulnerable if not individually negotiated,22 including preformulated standard contracts and terms over which the consumer has no substantial influence.23

Core terms about the adequacy of the price24 are not subject to the test of fairness, the only requirement being that such terms must be in plain intelligible language.25 An unfair term is any one which causes a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations to the detriment of the consumer (that is the borrower) contrary to requirement of good faith.26 The nature of the loan and the circumstances attending its completion must be considered. Factors are the relative bargaining positions of the

15SI 1998/996 (from May 1998); previously £15,000 (from mid 1985) and £5,000 (earlier). Some provisions do not apply to small agreements: SI 1983/1878.

16Either by a lender to a borrower (a debtor-creditor agreement) or involving a third party such as a double glazing supplier (a debtor-creditor-supplier agreement).

17Consumer Credit Act 1974 ss 58, 67–73; SI 1983/1557.

18SI 1983/1553; R v. Modupe [1991] Times February 27th, CA.

19Wilson v. First County Trust (No 2) [2001] EWCA Civ 633, [2001] QB 74; McGinn v. Grangewood Securities [2002] EWCA Civ 522, [2002] Times May 30th; Watchtower Investments v. Payne [2001] EWCA

Civ 1159, [2001] Times August 22nd.

20Sch 1 para 1(b); Electricity Supply Nominees v. IAF Group [1993] 1 WLR 1059; Havenridge v. Boston Dyers [1994] 2 EGLR 73, CA; Star Rider v. Inntrepreneur Pub Co [1998] 1 EGLR 53; Paragon Finance v.

Nash [2001] EWCA Civ 1466, [2002] 1 WLR 685.

21SI 1999/2083, as amended; S Bright & C Bright (1995) 111 LQR 655; JE Adams [1995] Conv 10. Excluded are eg contracts relating to succession or family arrangements. Consultation is taking place on a reform: Law Com CP 166 (2002).

22SI 1999/2083 reg 3(1).

23Regs 3(4)(3)–(4).

24Director General of Fair Trading v. First National Bank [2001] UKHL 52, [2002] 1 AC 481, held that a provision for charging interest on interest was not a core term, meaning that the fairness provisions applied, though the particular term was not unfair. See E Macdonald (2002) 65 MLR 763; M Dean (2002) 65 MLR

25Reg 3(2). Law Com CP 166 (2002) proposes a clearer link between what is a central term and the consumer’s expectation.

26SI 1999/2083 reg 4(1).

PROPER LENDING PRACTICE |

663 |

parties, inducements offered to accept particular terms, any adaption of the loan to a particular borrower, and the general course of dealings by the lender.27 Indicative examples of unfair terms are inappropriate exclusion of the lender’s liability, disproportionately high sums charged for breaches, terms with which the borrower had no opportunity to become acquainted, and terms allowing providing for unilateral alterations,28 as well as any term not in plain and intelligible language.29 The remainder of the loan contract will continue in force if, as is usual, the mortgage makes sense without it.30

C. PROPER LENDING PRACTICE

[30.08] Domestic borrowers are consumers who are entitled to expect lenders to act prudently, both for their own protection and to avoid leading borrowers into a debt trap. Administrative controls are tightening.31

1.Valuation of property

[30.09] Lenders should appoint a surveyor to report on the value of the property, which necessarily depends on the condition of the property. Proper lending practice allows a margin of at least 10% to cope with falls in property prices or a build up of arrears of interest. The value must be maintained by timely repair and by insurance against fire and other accidents.

A mortgage valuation is not a full structural survey of the property,32 but rather a check on value. Although the surveyor’s contractual duty of care is owed to the lender,33 some 85% of borrowers rely on the mortgage valuation when agreeing to buy. Smith v. Eric S Bush34 is the leading decision of the House of Lords. A surveyor, who had been appointed by a building society noticed that two chimney breasts had been removed, but did not check whether they were adequately supported. Had he done so he might have predicted the subsequent collapse of the chimney. The surveyor’s firm was held liable to the house buyer in tort since it was foreseeable that he would on the valuation. Liability for negligence was disclaimed by Eric S Bush, but since Smith was a domestic borrower protected against unfair terms35 and it was held that reliance on the exclusion clause was not reasonable. It would not be fair to exclude liability given the major commitment to a house purchase riding on a careless valuation.

27Sch 2; Falco Finance v. Michael Gough [1999] CLYB 2516 (charging interest on the whole loan under a reducing balance loan contravened the regulations; so too did a 5% increase in interest rate after a single default); S Bright (1999) 115 LQR 360.

28SI 1999/2083 sch 3 (taking only those apparently relevant to mortgages).

29Reg 6.

30Reg 8.

31This will be an important aspect of the FSA Mortgage Code; see above [30.05].

32Even that is not a guarantee: Watts v. Morrow [1991] 1 WLR 1421, CA; E Macdonald [1992] NLJ 632.

33Care is needed where an employee of the lender carries out a valuation: Halifax BS v. Edell [1992] Ch

34[1990] 1 AC 831, HL; there are many later cases.

35Unfair Contracts Terms Act 1977 s 2 subjects a disclaimer of liability for negligence to a test of reasonableness.

664 |

30. PROTECTION OF DOMESTIC BORROWERS |

Losses arising from a negligent valuation are limited to the difference between the valuation figure and the true market value at that time. Valuers cannot be held responsible for unforeseeable falls in the property market.36

2.Creditworthiness of borrower

[30.10] Modern domestic practice always involves some credit checks, though “over gearing” of commercial concerns is just as great a problem. Domestic borrowers usually borrow against their future income, which must be sufficient to service the repayments. A multiplier of 2.5 or 337 is applied to the gross annual salary, permitting a borrower earning £20,000 a year to borrow up to £60,000. After the sharp recession in the early 1990s more cautious lending guidelines have returned. Expensive precautions are insurance against illness or redundancy, and life cover to discharge the loan in the event of the death of one of the joint borrowers.

Domestic sector lenders ought to be required to behave professionally when lending, but there is little sign yet of a comprehensive liability in English law for reckless lending.

3.Guarding against mortgage fraud

[30.11] Mortgage fraud is all too prevalent. The criminal aspects are not considered here. The primary concern of the conveyancer is to carry out preventative checks to reduce the enormous scale of frauds.38 Many frauds involve misstatement of the identity of the applicant. Loan applications inaccurately stated the borrowers’ names, employment and income, their intended use of the property, and the purchase prices of the various properties used in the frauds. Often such frauds prevent a lender getting a valid security for the amount of his loan, but if he does and is able to recover his loan from sale of the security, the borrower is entitled to any surplus.39 Conveyancers can prevent many frauds by ensuring that they meet unknown clients and checking the stated identities. A receipt clause will not be decisive against a victim of a fraud.40

Other frauds involve the property. Sometimes non-existent land is mortgaged, a problem which will self-disclose when the lender tries to repossess it. Rollovers are the commonest fraud, by which land is sold at progressively higher prices using false valuations.41

36South Australia Asset Management Corporation v. York Montague [1997] AC 191, HL.

37Couples: 3 main income 1 smaller income, or 2.5 joint income. Otherwise additional security may be required. The rapid rise in house prices in the early years of the 2000s combined with low interest rates has led to many lenders stretching this to 5 or even 7 times salary.

38M Clarke, Mortgage Fraud (Chapman & Hall, 1991); HW Wilkinson [1993] Conv 181.

39Halifax BS v. Thomas [1996] Ch 217, CA; AC Spiers [1996] Conv 387; Portman BS v. Hamlyn Taylor Neck [1998] 4 All ER 202, CA.

40Scotlife Home Loans (No 2) v. Melinek (1999) 78 P & CR 389, CA.

41Target Holdings v. Redferns [1996] 1 AC 421, HL; Paragon Finance v. DB Thakerar [1999] 1 All ER 400, CA (limitation). There are many other cases.

INSTALMENT MORTGAGES |

665 |

4.Dual representation

[30.12] It is general practice for one solicitor to represent both borrower when acquiring the house and lender when advancing money to complete the acquisition.42 Dual representation was permitted in 197243 to avoid wasteful duplication.

5.Mortgage instructions

[30.13] Mortgage instructions are provided by lenders which determine the functions of a conveyancer when acting for the lender. The solicitor must obtain a valid mortgage. Land offered as security for a loan must be saleable, and easily saleable, so it is vital to investigate title before any money is advanced. After completion the solicitor must ensure that the mortgage is adequately protected by registration and must give notice of the mortgage to the holders of superior titles.44

Lenders must ensure that superior titles are kept on foot, with money spent for this purpose being added to the security. This includes interest on prior mortgages,45 rent under superior leases,46 and similar outgoings.

D. INSTALMENT MORTGAGES

[30.14] “Your home is at risk if you do not keep up payments on a mortgage or other loan secured on it.”47 This very necessary warning encapsulates two truths. Any debt carries with it the inherent risk of enforcement procedures, including ultimately loss of the property securing the debt. But this should only occur after a default – the key concept of modern mortgage law – with protection for domestic borrowers based on a loose distinction between minor remediable defaults and major arrears justifying immediate sale.48

1.Repayment mortgages

[30.15] Most mortgages provide for repayment of what is borrowed by instalments. A person who has borrowed to buy a home obviously cannot repay the money immediately, and needs to be allowed a period of years, common durations being 15, 20 or 25 years.49

42Procedure in a simple mortgage transaction was explained R v. Preddy [1996] AC 815, 828–829, Lord Goff. The borrower pays all fees.

43Solicitors Practice Rules 1988 r 6, as amended in 1998: [1998] 40 LSG 42; HW Wilkinson [1998] NLJ 1882.

44Council of Mortgage Lender Lender’s Handbook (2002 edition), available on the CML website.

45Re Leslie (1883) 23 Ch D 552 (add to security); Sinfield v. Sweet [1967] 1 WLR 1489 (no personal action).

46Brandon v. Brandon (1862) 10 WR 287.

47SI 1989/1125.

48J Houghton & L Livesey “Mortgage Conditions: Old Law for a New Century?” ch 10 in E Cooke (ed)

Modern Studies in Property Law 1 – Property 2000 (Hart, 2001).

49There may be a trend towards flexible mortgages allowing repayments to be varied and additional borrowing: J Morgan “Mortgages and the Flexible Workforce” ch 11 in Jackson and Wilde. Also, apparently, the growth of “100 year inter generational mortgages”.

666 |

30. PROTECTION OF DOMESTIC BORROWERS |

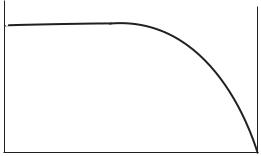

Instalments are calculated so that the balance of the debt (allowing for interest and capital repayments) will be reduced to zero at the end of the term of the loan. In the early years little capital is repaid but as inroads are made into the debt, the balance falls with increasing speed, rising to a gallop in the last few years.50

100K

Loan outstanding

0 |

10 |

20 |

25 |

|

|

Years |

|

Figure 30-1 A repayment mortgage

Interest rates are usually variable, in which case monthly payments will also vary.

2.Interest-only mortgages

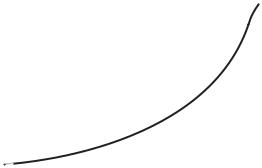

[30.16] Some mortgages provide for an advance over a fixed period of time, perhaps 25 years, with an agreement to leave the capital outstanding for the whole of that time. Interest is payable monthly but so long as the borrower keeps up to date with that, capital is deferred until the end of the fixed term of the mortgage.51 If B borrows £100,000 in the year 2000, he will owe £100,000 in the year 2025. Repayment may be funded by a prospective inheritance, but usually there is an associated investment vehicle designed to build up a lump sum sufficient to redeem the loan.

Endowment mortgages are linked to an insurance policy. A monthly premium is paid to an insurance company, which invests the accumulating premiums so as to build up a sum large enough to discharge the borrowing.52 Innocents abroad assume that any surplus belongs automatically to the owner of the house mortgaged, but ownership of the house and of the policy money may easily diverge.53 In a low interest rates environment, the fund manager may struggle to obtain a sufficient yield of investment income to pay off the mortgage loan, especially if the stock exchange falls, and half a million borrowers or more have been left with shortfalls, some very serious.54 However, if all goes well a surplus is generated, as illustrated below:

50A Samuels (1967) 31 Conv (NS) 343, 344; Falco Finance v. Michael Gough [1999] CLYB 2516.

51A default clause is essential in case interest payments lapse.

52The insurance policy is mortgaged to the lender, ensuring that it has first call on the money invested. This is by assignment (ie like a pre-1926 mortgage of land), notice of which must be given to the insurance company.

53Powell v. Osbourne [1993] 1 FLR 101; better is Smith v. Clerical Medical & General Life Assurance Society [1993] 1 FLR 47, CA; MC Hemsworth [1998] CLJ 15.

54Endowment Mortgages (FSA, PN/062, 2002).

INSTALMENT MORTGAGES |

667 |

|

|

|

|

100K |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Loan |

|

Policy |

outstanding |

|

|

|

(dotted line) |

|

(solid line) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

10 |

20 |

25 |

|

|

Years |

|

Figure 30-2 An endowment mortgage

Endowment mortgages have diminished in popularity because of tax changes and inflexibility; borrowers lose if the policy does not remain on foot for the whole 25 year expected life of a mortgage. A variety of other investment vehicles can be used to build up the lump sum to repay the loan – including pension lumps sums and personal equity plans.

3.Default clauses

[30.17] While agreed instalments are paid, there is no action for debt and no possibility of sale, so that security in his home is guaranteed to a punctilious borrower.55 Lenders need to ensure that their remedies are restored once arrears build up via a default clause which makes the whole loan payable if any instalment is in arrears for a stated period, commonly 14 or 21 days.56 Acceptance of a late instalment may waive a default57 but otherwise the courts have tended to take a tough line after there has been any default.58 Even without a default clause enforcement of the mortgage is usually allowed after any instalment is late,59 but there is a risk that either party will have the right to insist on earlier repayment.60

55De Borman v. Makkofaides (1971) 220 EG 805 (instalments but no interest!); Curteis v. Fenning (1872) 41 LJ Ch 791, Hatherley LC.

56Keene v. Biscoe (1878) 8 Ch D 201, Fry J (3 days); Leeds & Hanley Theatre of Varieties v. Broadbent

[1898] 1 Ch 343, CA (9 days); NL Macassey (1992) 122 NLJ 815. This is not a penalty: Wallingford v. Mutual Society (1880) 5 App Cas 685, 702, Lord Hatherley; Walsh v. Derrick (1903) 19 TLR 209, CA;

Congresbury Motors v. Anglo-Belge Finance Co [1969] 3 All ER 545, 553–554, Plowman J.

57Seal v. Gimson (1914) 110 LT 583.

58Maclaine v. Gatty [1921] 1 AC 376, HL; Coutts & Co v. Doutroon Investment Corp [1958] 1 WLR 116.

59Stanhope v. Manners (1763) 2 Eden 197, 28 ER 873; Edwards v. Martin (1856) 25 LJ Ch 284, (1858) 28 LJ Ch 49; Kidderminster MBBS v. Haddock [1936] WN 158; Payne v. Cardiff RDC [1932] 1 KB 241.

60Williams v. Morgan [1906] 1 Ch 804, Swinfen Eady J.

668 |

30. PROTECTION OF DOMESTIC BORROWERS |

E. DOMESTIC REPOSSESSION

1.Protected domestic mortgages

[30.18] Although sale is the real remedy, protection for domestic borrowers is provided at the stage of repossession, and a lender who is able to recover possession will be entitled to sell the property.61 Protection derives either from the Administration of Justice Act 197062 or the consumer credit legislation.63 The domestic sector marked out by the 1970 Act consists of mortgages secured on any dwelling-house, which must be a building and one used as a dwelling. Mixed use was discussed in Royal Bank of Scotland v. Miller64 in the context of Afrika’s nightclub with a caretaker’s three bedroom flat above which, it was decided, fell within the domestic protection. Possession cannot be deferred in relation to part only.65 The date on which to determine this question is when a claim is made for possession.66

The Law Commission proposes67 to formalise the distinction between commercial and domestic mortgages, drawn either according to the purpose of the loan or the use of the mortgaged property,68 with much more rigorous patrolling of domestic mortgages, including standardisation of terms,69 and the abolition of interest penalties and interest in lieu of notice to redeem. An enforcement notice would be required before any action could be taken, the need for enforcement proceedings would be clarified, and the existing powers to suspend possession would be refined.

2.Contractual exclusion of the right to possession

[30.19] Harman J’s judgment in Four Maids recognised that the lender could contract to restrict the normal right to possession.70 Older mortgages often contained an attornment clause, by which the borrower declared that he was a tenant at will or periodic tenant of the lender to take advantage of a superior repossession procedure, but this is no longer advantageous.71 Modern mortgages usually give an express right to possession so long as the borrower pays instalments promptly.

61Cheltenham & Gloucester v. Booker [1997] 1 EGLR 142, CA.

62S 36, as amended by Administration of Justice Act 1973 s 8; B Rudden (1961) 25 Conv (NS) 278; C Glasser (1971) 34 MLR 61; H Wallace (1986) 37 NILQ 336; HW Wilkinson [1990] NLJ 823; updaters by D McConnell in Legal Action; L Whitehouse “The Home Owner: Citizen or Consumer?” ch 19 in Bright & Dewar; Megarry & Wade (6th ed), [19.067–19.083].

63See below [30.32].

64[2001] EWCA Civ 344, [2002] QB 255; RJ Smith [1979] Conv 266, 270–271.

65Barclays Bank v. Alcorn [2002] March 11th, Hart J; L McMurty [2002] Conv 594.

66Royal Bank of Scotland v. Miller at [25], Dyson LJ.

67Law Com 204 (1991); GH Griffiths [1987] Conv 191; HW Wilkinson [1992] Conv 69; GH Griffiths [1992] JBL 423; G Frost (1992) 136 SJ 267, 292.

68Probably, any mortgage involving a dwelling-house unless the borrower is a body corporate and enforcement would not affect any residential occupier.

69Including obliging the lender to keep the deeds safe, giving a borrower the right to possession unless the lender takes it, requiring repair, limiting sale to arrears of instalments or other major breach, and preventing the borrower granting leases without the consent of the lender.

70Four Maids v. Dudley Marshall [1957] Ch 317, 320; see above [29.15].

71Peckham Mutual BS v. Registe (1982) 42 P & CR 186, Vinelott J; Alliance BS v. Pinwill [1958] Ch 788; and many other cases.

DOMESTIC REPOSSESSION |

669 |

3.Judicial power to defer possession

[30.20] Legislative protection for domestic borrowers was introduced in two stages, the parent provision being section 36 of the Administration of Justice Act 1970. Possession proceedings brought by a mortgage-lender72 may be suspended where it appears that the borrower is likely to be able to pay any sums due within a reasonable period or to remedy any other default. It follows that the first task is to determine precisely what default has occurred.73 Minor arrears no longer gave a right to immediate possession. Although the intended target was arrears, the statute failed to land a clean hit when it referred to “any sums due under the mortgage”. Unfortunately in the case of an instalment mortgage containing a default clause this could, on a literal reading,74 means the entire capital balance, though a purposive reading limiting the sum to be paid off to the arrears was obviously intended.75

Section 8 of the Administration of Justice Act 197376 solves this problem where the borrower is entitled to pay by instalments or where he is entitled or permitted to defer payment. The court applies its discretion to the amount of the arrears ignoring the impact of any default clause. “Sums due” are what the borrower expected to be required to pay, ignoring any provision for earlier payment. Arrears must be cleared within a reasonable time along with current instalments as they fall due, but not the whole capital balance.

4.Other cases of deferral

[30.21] Permanent investment mortgages leave the loan outstanding after the contractual redemption date, until it is made repayable by serving a calling in notice. Under the 1970 Act (viewed in isolation) the court should order possession unless the borrower is able to repay all “sums due under the mortgage” – that is the whole redemption money – by the end of the notice calling in the capital, and could also foreclose.77 Section 8(1) of the 1973 Act, however, allows the court to ignore any sum of which the borrower is permitted “to defer payment” “otherwise” meaning as a matter of grace.78 In Centrax Trustees v. Ross79 the court ignored a calling in notice, meaning that the borrower was only required to keep up to date with interest, though this was certainly not intended.80

72A “mortgagee”, which includes the lender under a charge, and any successor: s 39.

73Halifax Mortgage Services v. Muirhead (1997) 76 P & CR 418, 428, Evans LJ; Ladjadj v. Bank of Scotland [2000] 2 All ER (Comm) 583, CA.

74Halifax Building Society v. Clark [1973] Ch 307, Pennycuick V-C (arrears £1,000, redemption figure £1,400); PV Baker (1973) 89 LQR 171; P Jackson (1973) 36 MLR 550; EH Scammell (1973) 37 Conv (NS) 133, 213; Bank of Scotland v. Grimes [1985] QB 1179, 1190, Griffiths LJ.

75First Middlesborough Trading and Mortgage Co v. Cunningham (1974) 28 P & CR 69, 74, Scarman LJ; Cheltenham & Gloucester BS v. Norgan [1996] 1 WLR 343, 345D–348A, Waite LJ; Cheltenham & Gloucester

v.Krausz [1997] 1 WLR 1558, CA.

76(1973) 123 NLJ 475; S Tromans [1984] Conv 91.

77S 36(1) does not apply; Cheltenham & Gloucester BS v. Grattidge (1993) 25 HLR 454, CA; Habib Bank

v.Tailor [1982] 1 WLR 1218, 1222A–B, Oliver LJ.

78RJ Smith [1979] Conv 266, 274. Forfeiture is similarly restricted.

79[1979] 2 All ER 952, Goulding J.

80Habib Bank v. Tailor [1982] 1 WLR 1218, 1224E, Oliver LJ.