- •1. Introduction

- •2. Duty of care

- •2.1. Regulatory structure

- •2.2. Behavioural expectations

- •2.3. Business judgment rule

- •3. Duty of loyalty

- •3.1. Regulatory structure

- •3.2. Related party transactions

- •3.3. Corporate opportunities

- •4. Enforcement

- •4.1. Derivative action

- •4.2. Ease of enforcement

- •5. Directors’ duties in the vicinity of insolvency

- •5.1. Duty to file and wrongful trading

- •5.2. Changes to the core duties owed by directors

- •5.3. The “re-capitalise or liquidate” rule

- •5.4. Additional elements of a regulatory response to near-insolvent trading

- •6. Conclusion

transaction.65 Of course, this is ultimately not a problem inherent in two-tier board structures, but a matter of definition. The two-tier solution of reallocating decision-making power could be designed so as to encompass also indirect conflicts.66 Arguably, however, the no-conflict rule that originated in English common law can be interpreted more easily in an expansive way to capture different types of conflict.

3.3. Corporate opportunities

Corporate opportunities can be defined as business opportunities in which the corporation has an interest. The effectiveness of the regulation of corporate opportunities thus depends on two factors. First, is the exploitation of corporate opportunities by the directors for their own account restricted and, if yes, under what conditions (disclosure, disinterested approval, etc.) are the directors free to pursue a business opportunity that belongs to the corporation? Second, how is it determined when a business opportunity “belongs” to the corporation? With respect to both dimensions, the law may adopt a narrow approach (i.e., the regulation is applicable to a narrowly defined set of cases) or a broad approach (applicable to a wide range of directors’ activities). It could be said that the narrow approach imposes a smaller risk of liability on directors and facilitates the realisation of business opportunities, which may contribute to an efficient allocation of resources, while the broad approach ensures a more comprehensive protection of shareholders. For example, as far as the first dimension is concerned, the law may only address direct conflicts of interest, i.e. where the director himor herself exploits a corporate opportunity (narrow approach), but not indirect conflicts created by the activities of a company or other business association in which the director has an interest (broad approach). As far as the second dimension is concerned, the law may define the necessary link between the business opportunity and the company narrowly, requiring the opportunity to fall within the line of business actually pursued by the company or identified as one of the company’s objects in the articles of association, or broadly, capturing for example any type of economic activity and disregarding the capacity of the company (financial or otherwise) to make use of the opportunity.

The Member States employ two general strategies to regulate corporate opportunities. One group of countries67 impose a fairly broad duty on directors not to exploit any information or opportunity of the company, as this would constitute a case of prohibited conflict of interest, and a second, larger group relies on the duty not to compete with the company. No country establishes an absolute prohibition. All jurisdictions allow directors to exploit corporate opportunities after authorisation by the board of directors, supervisory board, or general meeting of shareholders, as applicable.

In most jurisdictions the rules apply both to direct conflicts (the director himor herself takes advantage of the opportunity) and indirect conflicts (the director is involved in a business that engages in activities that are potentially or actually of economic interest to the company). The legal systems differ in details, for example with respect to the question of when the interest of the director in a competing business is significant enough to trigger the prohibitions of the no-conflict or non-compete rule or when the activities of a person affiliated with the director implicate the director. But all legal

65OLG Saabrücken, AG 2001, 483.

66This is the case in Slovenian law, which requires authorisation by the supervisory board where the director (or a family member) holds 10% or more of the share capital, is a silent partner, or participates in any other way in the profits of another undertaking that transacts with the company, see Companies Act, Art. 38a.

67In particular, those belonging to the common law.

15

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2249050

systems that regulate these conflicts provide for some mechanism that goes beyond the purely formal director-company relationship and includes affiliates that are economically identical or closely related to the director.

The Member States differ systematically with regard to the second dimension: the definition of the necessary link between the business opportunity and the company. Interestingly, the difference correlates with the regulatory strategy employed by the legal system, the duty not to exploit corporate opportunities or the prohibition to compete with the company. Jurisdictions adopting the former strategy generally provide for duties that encompass all cases of an actual or potential conflict, i.e. the director is prohibited from exploiting the business opportunity notwithstanding the company’s current activities or financial means. The non-compete rule, on the other hand, is generally interpreted narrowly. “Competing with the company” is understood as pursuing an economic activity within the scope of the company’s business, i.e. engaging in actual, not only potential, competition with the company.

However, it is not clear that this correlation lies in the nature of the regulatory strategy adopted. Essentially, this is a simple matter of how the boundaries of the no-conflict and non-compete duties are defined and interpreted. For example, Portugal’s company law contains a codified version of the non-compete duty.68 In addition, it is argued that an unwritten corporate opportunities doctrine exists that applies if the business opportunity falls within the company’s scope of activity or the company has expressed an interest in the opportunity and received a contractual proposal or is in negotiations.69 Thus, the definition of “corporate opportunity” is narrower than the one developed by, for example, the English courts.70 In this manner, the corporate opportunities doctrine and the codified duty not to compete with the company are aligned. On the other hand, under the heading “prohibition of competition”, Austria and Germany prohibit directors from operating any other business enterprise, notwithstanding its line of business.71 Nevertheless, it may be argued that the structure of the corporate opportunities doctrine as found in common law jurisdictions is more conducive to an openended, flexible interpretation, given that it is based on a broadly understood requirement to avoid conflicts of any kind, whereas the use of the term “competition” implies a proximity of the prohibited activity and the company’s business. On this view, the differences in the scope of the prohibition would be a natural consequence of the different legal strategies initially adopted.

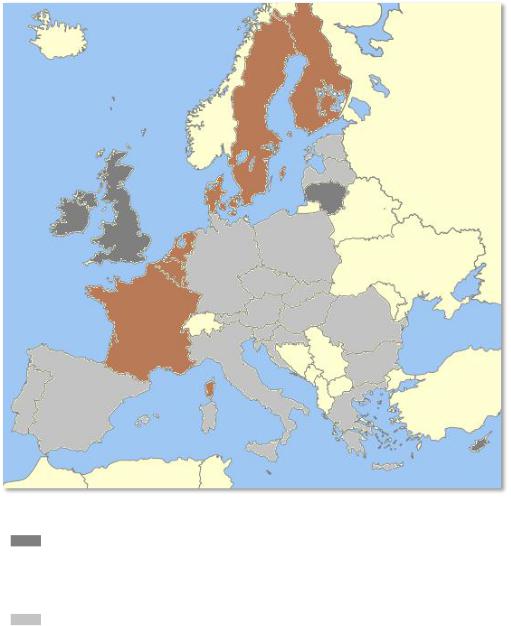

On the basis of these considerations, the Member States may be divided into the following groups, which are depicted in Map 3 below.

(1)The broad approach is based on what can be called the “no-conflict rule”: Directors are required to avoid any type of conflict of interest with the company, which means in this

context that they must refrain from exploiting business opportunities. As explained, the legal systems that employ this approach define the term “corporate opportunity” broadly,

68Portuguese Code of Commercial Companies, Art. 398(3).

69Jorge Manuel Coutinho de Abreu, Deveres de cuidado e de lealdade dos admnistradores e interesse social, in

Reformas do Código das Sociedades (N.º 3 da Colecção, Almedina 2007), 17, 26-27.

70See, e.g., Regal (Hastings) Ltd v Gulliver [1942] 1 All E.R. 378 (House of Lords); Wilkinson v West Coast Capital [2005] EWHC 3009; O’Donnell v Shanahan, [2009] EWCA Civ 751. For a comprehensive analysis of the case law see Paul Davies and Sarah Worthington, Gower and Davies’ Principles of Modern Company Law (Sweet & Maxwell, 9th ed. 2012), paras. 16-145 to 16-164.

71Austrian Stock Corporation Act, § 79(1); German Stock Corporation Act, § 88(1). Similar the Slovenian Companies Act, Art. 41.

16

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2249050

encompassing any business opportunity that is actually or potentially of economic interest to the company. The prohibition does not only apply if the company has expressed an interest in the opportunity or it can be assumed that such an interest exists because of the close link with the company’s current operations. The theoretical possibility of a (future) overlap with the company’s activities is sufficient. In addition, the financial capacity of the company to exploit the opportunity is irrelevant.

(2)The narrow approach relies on the duty not to compete with the company. The director is generally only required to refrain from pursuing opportunities in the company’s line of business.

(3)Finally, the third group comprises jurisdictions that do not contain any binding regulation of corporate opportunities, either by way of a statutory no-conflict or non-compete provision or a well-established case-law based corporate opportunities doctrine.

Map 3: Corporate opportunities

Legend |

Country |

Duty not to make use of corporate |

CY, IE, LT, MT, UK |

opportunities (broad definition, i.e. |

|

not requiring that the director must |

|

act in the company’s line of |

|

business) |

|

Duty not to compete (narrow |

AT, BG, CZ, DE, EE, EL, HR, HU, IT, LV, |

|

|

17

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2249050

definition, i.e. generally requiring |

PL, PT, RO, SI, SK, ES72 |

that the director must act in the |

|

company’s line of business) |

|

No binding regulation |

BE, DK, FI, FR, LU, NL, SE |

The common law countries Ireland and the UK, as well as the mixed jurisdictions strongly influenced by English common law (Cyprus and Malta), but also Lithuania have developed a corporate opportunities doctrine stemming from the duty to avoid conflicts of interest. The paradigm of this doctrine, and its most developed version, can be found in the UK. The UK courts have produced a wealth of case law on corporate opportunities that have shaped the details of the doctrine and clarified that: (1) directors do not have to learn of the corporate opportunity in their capacity as director, but it is sufficient that they obtain knowledge of the opportunity in a private capacity, for example during their spare time; (2) it is irrelevant whether the corporate opportunity falls within the company’s line of business or not, as long as the possibility is not excluded that the company may now or in the future adjust or refocus operations so that the business opportunity becomes economically interesting to the company; and (3) the fact that the company is currently unable to exploit the opportunity for financial reasons or because of the existence of a legal impediment (e.g., a restricted objects clause in the company’s articles) that may be removed through appropriate action (for example, a resolution by the general meeting amending the objects clause) is immaterial.73

In the other jurisdictions inspired by the English principles, the reach of the corporate opportunities doctrine is often less clear than in the UK. This is generally not a function of a conscious deviation from the English law, but simply of the paucity of case law that could settle these questions. Often the literature discusses in how far the English principles should apply, but the smaller size of the

72 Portugal, Italy, and Spain provide both for a corporate opportunities doctrine and a duty not to compete with the company. As discussed supra text to notes 68-69, the (unwritten) Portuguese corporate opportunities doctrine is formulated narrowly. Therefore, we assign Portugal to group 2. In Italy and Spain, the corporate opportunities doctrine was introduced fairly recently into the Civil Code and the Corporate Enterprises Act, respectively, see Italian Civil Code, Art. 2391(5), as amended by Legislative Decree No. 6 of 17 January 2003, Gazz. Uff. n.17 (22 January 2003); Spanish Corporate Enterprises Act, Art. 228; a regulation was initially proposed by the Olivencia Code of Good Governance of 1998, s. 8.4. The traditional approach to regulating these issues was by means of the prohibition to compete, which remains in force, Italian Civil Code, Art. 2390; Spanish Corporate Enterprises Act, Art. 230. It is uncertain how the two provisions relate to each other and what the reach of the corporate opportunities doctrine is. Case law is scarce or non-existent. We accordingly assign these two countries to group 2 as well.

Other ambivalent cases are Austria, Germany and Slovenia (see supra n 71 and accompanying text). These jurisdictions distinguish between two types of activity: The operation of another business enterprise and the conclusion of transactions. The former is prohibited in a general and comprehensive way, notwithstanding the scope of the other enterprise’s business, in order to ensure that the directors devote their undivided attention to the company. Therefore, this part of the prohibition is not, in essence, a non-compete rule, but concerns a more general conflict of interest. The latter prohibition only applies if the director is active within the company’s line of business and follows the traditional non-compete rules that can be found in other jurisdictions. Consequently, the three jurisdictions stand somewhat between group 1 and group 2. In addition, particularly German law is flexible in that the existence of an unwritten duty of loyalty is accepted, which was used by the courts to address cases not caught by the codified duty (see, for example, BGH WM 1967, 679, where the court held that the director was in breach of fiduciary duties by acquiring property that was not required by the company for its current operations).

73 See the references supra n 70.

18

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2249050

jurisdiction and possibly non-legal reasons for the less frequent use of the judicial system mean that the courts did not have the possibility to decide on the issue or develop their distinct solutions.74

Is the common law approach superior to the second strategy, the duty not to compete, which is employed mostly by jurisdictions from the French and German legal families? In many cases, the outcome of corporate opportunity cases will be the same under both strategies. If a director pursues an opportunity through another business, he or she will be liable pursuant to both approaches. However, the results are different if the director exploits the opportunity in his or her personal capacity, which would not qualify as operating a competing business. In addition, as mentioned above, if the corporate opportunities doctrine is interpreted broadly, it captures business opportunities outside of the company’s line of business, as well as opportunities that cannot be exploited by the company due to financial incapacity or some other (non-structural) impediment75 or that are declined by the company. In these instances, a non-compete rule that is triggered by actual competition may not apply. Conversely, in the absence of a statutory or contractual duty not to compete, a director would be free to serve on the board of a competing company, as long as the director does not exploit any corporate opportunity. Thus, in theory, jurisdictions that employ only the corporate opportunities doctrine may not prohibit conduct potentially detrimental to the interests of the director’s company.76 In practice, however, it is unlikely that the corporate opportunities doctrine leads to regulatory loopholes. If the companies operate in the same line of business, they will inevitably encounter business opportunities attractive to both companies. In addition, in jurisdictions following the English common law, the corporate opportunities doctrine is embedded in the general no-conflict rule, which is flexible in its scope of application and may well be used by the courts to intervene and hold the director responsible where the companies engage in actual competition.77

Finally, several jurisdictions do not contain any binding rules in the company legislation and have also not developed a corporate opportunities doctrine along the lines of the common law jurisdictions: France, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and the Scandinavian jurisdictions. However, this does not mean that the issue is left without any regulation. The service contract concluded with the director may contain a non-compete clause, with the consequence that directors are contractually liable if they engage in competitive behaviour. This is common practice in most jurisdictions. In addition, the legal mechanisms of the jurisdictions in this group are, in general, flexible enough to address the usurpation of corporate opportunities by the director. In French law, the existence of a general duty of loyalty is commonly acknowledged, although the legal basis of the duty is somewhat

74See, for example, Deirdre Ahern, Directors’ Duties: Law and Practice (Thomson Round Hall 2009), paras. 7-

40to 7-57 (Ireland); Andrew Muscat, Principles of Maltese Company Law (Malta University Press 2007), pp. 452-459 (referring to both English and US law in analysing Maltese company law); Elias A. Neocleous, Kyriacos Georgiades, and Markus Zalewski, Corporate Law, in Dennis Campbell (ed.), Introduction to Cyprus Law (Yorkhill Law Publishing 2000), paras. 9-42 to 9-44.

75For a discussion of the distinction between ‘structural impediments’ and practical inability’ see Kershaw, supra n 50, p. 552.

76This was indeed the position under early English common law, see London and Mashonaland Co Ltd v New Mashonaland Exploration Co Ltd [1891] WN 165.

77Several English judgments (predating the Companies Act 2006) can be understood in this sense, see Bristol & West Building Society v Mothew [1998] Ch. 1; CMS Dolphin Ltd v Simonet [2002] B.C.C. 600. Some Irish cases also suggest that this is the case, see Spring Grove Services (Ireland) Ltd v O’Callaghan, High Court, unreported, Herbert J., July 31, 2000.

19

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2249050

unclear.78 In addition, it was argued by some French commentators that the exploitation of corporate opportunities may constitute the criminal offence of l’abus de biens sociaux.79 In Belgium, liability for disloyal behaviour is based on the general provision establishing responsibility of directors for management mistakes and failures to exercise their mandate properly.80 In Luxembourg, the duty of loyalty can also be derived from general provisions, but the courts tend to be reluctant to intervene in cases of competitive behaviour or the exploitation of corporate opportunities by directors, given the generally liberal approach inherent in Luxembourg company law.81 In the Netherlands, general principles of, for example, the duty of care or tort law, have been utilised in some cases to arrive at suitable solutions.82 In Finland, the duty of directors to ‘promote the interests of the company’, set out as a general principle in Part 1 of the Finnish Limited Liability Companies Act,83 is interpreted broadly as the statutory basis of an unwritten duty of loyalty. Directors who take advantage of corporate opportunities may be judged as not having promoted the interests of the company. Similarly, in Sweden the lack of an explicit regulation of corporate opportunities or competitive behaviour is potentially compensated for by an application of the duty loyalty.84

This analysis indicates that in all three groups, the law seems elastic enough to be able to address conflicts where regulatory intervention is deemed expedient, notwithstanding the regulatory technique employed by the legal system. Even jurisdictions with no express regulation of corporate opportunities and no comprehensively codified duty of loyalty have achieved results driven by case law and judicial innovation that are similar to UK law, which may be regarded as the paradigmatic case of the corporate opportunities doctrine.85 The main difference with regard to outcomes seems to be the increased legal uncertainty due to the lack of clearly specified rules addressing different conflict situations. In most jurisdictions of group 3, the scope of the prohibitions to compete with the company and exploit corporate opportunities is evolving and authoritative case law is scarce. It should be emphasised that this is not a result of the lack of codified rules, but more generally of clearly specified rules, which may derive from statutory law or case law, as can be seen in the UK, where the corporate opportunities doctrine was, of course, entirely case-law based until 2006. Arguably, however, the distillation of rules tailored to specific conflict situations from general (and possibly unwritten) principles of law requires that certain conditions are satisfied, notably that the courts have the opportunity to adjudicate and refine the legal principles.

78See supra n 56 and for a more detailed discussion Philippe Merle, Sociétés commerciales (15th ed., Dalloz 2011), para. 388.

79Maurice Cozian et al., Droit des sociétés (Lexis Nexis, 20th ed. 2007), para. 617.

80Art. 527 of the Code des Sociétés provides: ‘Les administrateurs . . . sont responsables, conformément au droit commun, de l’exécution du mandat qu’ils ont reçu et des fautes commises dans leur gestion.’

81See André Prüm, Luxembourg company law – a total overhaul, in Michel Tison et al. (eds.), Perspectives in Company Law and Financial Regulation: Essays in Honour of Eddy Wymeersch (Cambridge University Press 2009), 302, 303-304 and passim.

82See for example Court of Appeals Arnhem, 29 March 2011, LJN BQ0581, JOR 2011/216, holding a director liable for starting a competing business on the basis of sections 2:8 and 2:9 Dutch Civil Code.

83Ch. 1, s. 8.

84Rolf Dotevall, Liability of Members of the Board of Directors and the Managing Director – A Scandinavian Perspective, 37 Int’l L. 7, 20-21 (2003).

85See supra n 72 (German law).

20

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2249050