- •1. Introduction

- •2. Duty of care

- •2.1. Regulatory structure

- •2.2. Behavioural expectations

- •2.3. Business judgment rule

- •3. Duty of loyalty

- •3.1. Regulatory structure

- •3.2. Related party transactions

- •3.3. Corporate opportunities

- •4. Enforcement

- •4.1. Derivative action

- •4.2. Ease of enforcement

- •5. Directors’ duties in the vicinity of insolvency

- •5.1. Duty to file and wrongful trading

- •5.2. Changes to the core duties owed by directors

- •5.3. The “re-capitalise or liquidate” rule

- •5.4. Additional elements of a regulatory response to near-insolvent trading

- •6. Conclusion

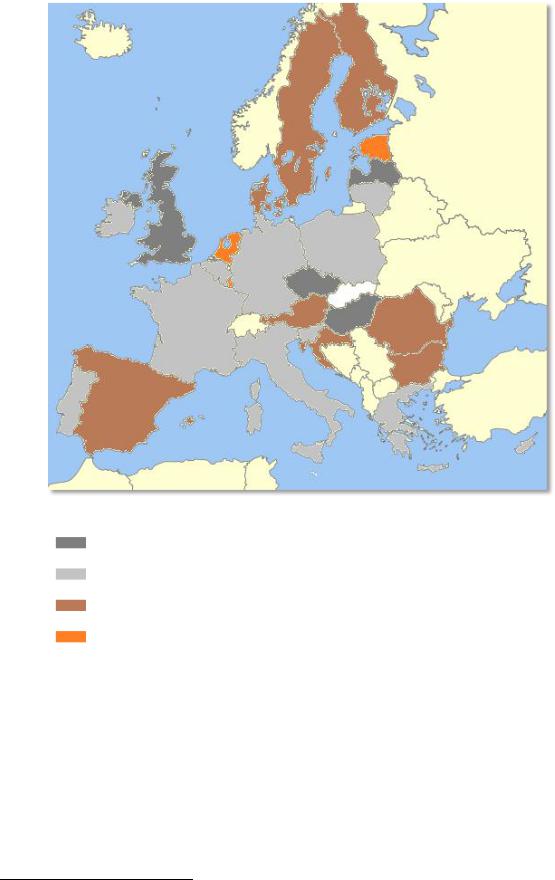

Map 7: Minority shareholder enforcement index

Legend |

Country |

Total score of the enforcement |

CZ, HU, LV, UK |

index of 10-11 |

|

Total score of 8-9 |

BE, CY, FR, DE, EL, IE, IT, LT, PL, PT, SI |

|

|

Total score of 6-7 |

AT, BG, HR, DK, FI, RO, SK, ES, SE |

|

|

No derivative action |

EE, LU, NL |

|

|

5.Directors’ duties in the vicinity of insolvency

As is evident from the preceding sections, Member States differ significantly in the definition of their behavioural expectations towards company directors, as well as in relation to the legal strategies they use to ensure that directors meet these expectations. Jurisdictions of course also differ in relation to their definition of concepts such as the “interest of the company”, with some countries using the concept almost synonymously with shareholder interests, while others use broader, more “inclusive” definitions, so as to also include stakeholders – primarily creditors and employees, or even the public interest as such.100 The structure of boards also has an important impact on the functioning and

100 See e.g. explicitly the Austrian Stock Corporation Act, s. 70.

29

ElectronicElectroniccopycopy availableavailable at:at: https://ssrnhttps://ssrn.com/abstract=2249050.com/abstract=2249050

performance of a board,101 including on directors’ attitudes towards risk,102 and employee participation in particular may have a considerable impact on how directors’ duties operate. These and many other factors, including executive remuneration, may of course profoundly affect the extent to which the interests of different corporate constituencies are taken into account in managerial decision making.

Directors’ duties have, in most jurisdictions, primarily been shaped with a view to the managerial agency problem. Depending on the prevalent corporate landscape in a particular jurisdiction, possible conflicts between majority and minority shareholders will also play a role in the legislative design of directors’ duties. Underlying this approach is, of course, the notion of shareholders as residual riskbearers within the corporation.103 This view is based on the company possessing a substantial amount of equity capital – the value at risk from the shareholders’ perspective – and it is thus rendered increasingly problematic as a company approaches insolvency. Once equity capital starts

“evaporating”, the economic risk borne by shareholders likewise disappears, which in turn leads to changed incentives on their part and on the part of directors.104 In this situation, the economic risk is mainly borne by the company’s creditors, who now increasingly look like the residual claimants.105

As a consequence, shareholders as well as directors can be expected to have privately optimal risklevels that exceed the social optimum: while shareholders will often effectively control the use of the distressed company’s remaining assets, the devaluation of their residual claim means that they can externalise the costs of risky projects (limited downside) while fully keeping the claim to a project’s potential profits (unlimited upside). Of course, shareholders always benefit from a limited downside due to limited liability. However, in well-capitalised firms, the risks flowing from most business projects will not be of a scale so as to wipe out the entire equity capital of a company if they materialise. Thus, losses of most projects will be borne (almost) entirely by shareholders, which creates a prima-facie case for their efficient decision-making. In near-insolvent firms, on the other hand, the asymmetry of shareholders’ pay-outs becomes much more important, as all or most business projects pose a threat to the thin layer of remaining equity. Consequently, shareholders are unlikely to

101 See e.g. Klaus Hopt, Modern Company and Capital Market Problems: Improving European Corporate Governance after Enron, in John Armour and Joseph A. McCahery (eds.), After Enron: Improving Corporate Law and Modernising Securities Regulation in Europe and The U.S. (Hart 2006), pp. 445, 453; Paul Davies, Board Structure in the UK and Germany: Convergence or Continuing Divergence? 2 International and Comparative Corporate Law Journal 435 (2001); Carsten Jungmann, The Effectiveness of Corporate Governance in One-Tier and Two-Tier Board Systems: Evidence from the UK and Germany, 4 European Company and Financial Law Review 426 (2006).

102See e.g. Ann B. Gillette, Thomas H. Noe and Michael J. Rebello, Board Structures Around the World: an Experimental Investigation, 12 Review of Finance 93 (2008).

103See e.g. Jaap Winter et al., Report of the High Level Group of Company Law Experts on a Modern Regulatory Framework for Company Law in Europe (Brussels, 2002), available at <http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/company/docs/modern/report_en.pdf> (last accessed 12 March 2013) at 7:

“Being the residual claimholders, shareholders are ideally placed to act as a watchdog”. See also Paul Davies,

Directors’ Creditor-Regarding Duties in Respect of Trading Decisions Taken in the Vicinity of Insolvency, 7 European Business Organization Law Review 301 (2006).

104See e.g. Davies, ibid; Horst Eidenmüller, Trading in Times of Crisis: Formal Insolvency Proceedings, workouts and the Incentives for Shareholders/Managers, 7 European Business Organization Law Review 239 (2006); Thomas Bachner, Wrongful Trading – A New European Model for Creditor Protection?, 5 European Business Organization Law Review 293 (2004).

105Davies, ibid, at 324.

30

ElectronicElectroniccopycopy availableavailable at:at: https://ssrnhttps://ssrn.com/abstract=2249050.com/abstract=2249050

be efficient decision-makers under these circumstances, as they do not have to internalise the costs of their decisions. Instead, they have an incentive to try and “gamble” their way out of insolvency.106

Similarly, insolvency is very costly for directors, even non-shareholder directors, due to the risk of reputational losses as well as the firm-specific human capital they invested in the firm. Absent legal constraints, high-risk strategies that may either lead to a recovery of the firm or the aggravation of the insolvency would thus be tempting for directors, unless they share the costs inflicted on creditors by risky business decisions taken in the vicinity of insolvency. In addition, where directors’ duties are designed primarily to align interests of shareholders and managers, leaving in place the “normal arrangements” – i.e. the regulatory approach designed with financially stable companies in mind – would incentivise directors to pursue the projects shareholders prefer, which as mentioned above would be inefficient.107

All EU Member States have developed legal responses to address this problem of possibly inefficient risk-shifting in the vicinity of insolvency. We identify four main legal strategies used by Member States in this context.

First, the majority of Member States impose a separate duty on company directors to file for the opening of insolvency proceedings upon the company reaching certain pre-defined insolvency triggers, with liability attached to a failure to timely make the relevant filing. Second, in some Member States no formal duty to file for insolvency exists; instead, liability attaches to directors for

“wrongful trading”, i.e. the continuation of business activities beyond a particular “triggering point”.108 Third, in some jurisdictions the content of directors’ duties changes as the company approaches insolvency, particularly by requiring directors to act in the interests of creditors, or at least take into account their interests. Fourth, the Second Company Law Directive109 provides for a duty to call a general meeting in case of a “serious loss”, which is defined as a loss of half110 of the subscribed share capital (i.e. the reduction of the company’s net assets to less than half the share capital).111 In implementing what is now Article 19 of the Directive, some Member States require shareholders to resolve on a recapitalisation of the company or else its winding up. This “recapitalise or liquidate”- rule addresses the problem set out above in so far as it tries to reduce the number of (public)112 companies that operate with very low capital levels.113

106 See also Carsten Gerner-Beuerle and Edmund Schuster, The Costs of Separation: Frictions between Company Law and Insolvency Law in the Single Market, [REFERENCE] (2013) at [REF].

107See also the detailed analysis by Eidenmüller, supra n 104.

108See in particular the UK Insolvency Act 1986, s. 214(2)(b), defining this triggering point with reference to the moment where ‘there was no reasonable prospect that the company would avoid going into insolvent liquidation’.

109See now Directive 2012/30/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 on coordination of safeguards which, for the protection of the interests of members and others, are required by Member States of companies within the meaning of the second paragraph of Article 54 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, in respect of the formation of public limited liability companies and the maintenance and alteration of their capital, with a view to making such safeguards equivalent, OJ L 315/74.

110See ibid, Art. 19; Member States can also set the threshold for serious losses at a lower level, ibid Art. 19(2).

111This is assessed on a cumulated basis; see Jonathan Rickford, Reforming Capital: Report of the Interdisciplinary Group on Capital Maintenance, 15 European Business Law Review 919, 940 (2004).

112See Annex I of the Second Directive, supra n 109.

113But see infra, text to n 127.

31

ElectronicElectroniccopycopy availableavailable at:at: https://ssrnhttps://ssrn.com/abstract=2249050.com/abstract=2249050

The following table provides an overview of the use of the four main strategies in the EU Member States.114

Table 3: Legal strategies in the vicinity of insolvency

|

Member State |

|

Duty to file or |

Change of duties |

Convene or |

|

wrongful trading |

recapitalise |

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Austria |

duty to file |

no115 |

convene GM |

|

|

Belgium |

duty to file |

no |

convene GM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bulgaria |

duty to file |

no |

recapitalise |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Croatia |

duty to file |

no |

convene GM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cyprus |

wrongful trading |

yes |

convene GM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Czech Republic |

duty to file |

no |

recapitalise |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Denmark |

hybrid approach |

yes |

convene GM |

|

|

|

(both)116 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Estonia |

duty to file |

yes |

recapitalise |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Finland |

duty to file |

no |

convene GM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

France |

duty to file |

no |

recapitalise |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Germany |

duty to file |

no |

convene GM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Greece |

duty to file |

no |

convene GM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hungary |

duty to file |

yes |

convene GM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ireland |

wrongful trading |

yes |

convene GM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Italy |

duty to file |

no |

recapitalise |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Latvia |

duty to file |

yes |

recapitalise |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lithuania |

duty to file |

no |

recapitalise |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luxembourg |

duty to file |

no |

recapitalise |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Malta |

duty to file |

yes |

convene GM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Netherlands |

wrongful trading |

no |

convene GM |

|

|

|

prohibition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Poland |

duty to file |

no |

convene GM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Portugal |

duty to file |

no |

recapitalise |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Romania |

wrongful trading |

no |

convene GM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Slovakia |

duty to file |

no |

convene GM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

114Adapted from Gerner-Beuerle et al., supra n 2, at 214.

115No formal change of duties, but the acceptability of risk-taking is reduced once the company’s financial position reaches critical levels; see generally Christian Nowotny in Peter Doralt, Christian Nowotny, and Susanne Kalss (eds.), Kommentar zum Aktiengesetz (2nd ed, Manz 2012) at § 84 No 9.

116Case law has established a rule similar to the UK wrongful trading prohibition. Directors who know (or should have known) that the company has no reasonable prospect of avoiding insolvency must minimise the potential losses to creditors or will be liable. In addition, a duty to file for insolvency applies.

32

ElectronicElectroniccopycopy availableavailable at:at: https://ssrnhttps://ssrn.com/abstract=2249050.com/abstract=2249050