Учебный год 22-23 / Firms, Contracts, and Financial Structure

.pdf170 |

II. UNDERSTANDING FINANCIAL STRUCTURE |

class of shareholders, and then putting the company's future to a simple vote. The AHM procedure also avoids bargaining over the division of the pie, since it uses a mechanical scheme for distributing shares that preserves absolute priority. (The scheme is due to Lucian Bebchuk; see Bebchuk 1988.)189

It turns out that the idea behind the proposal is more important than the details. Thus, there are several versions of the procedure, all of which are consistent with the same basic philosophy. Two versions are presented here. They differ with respect to their treatment of secured debt and with respect to the role played by the judge, or bankruptcy practitioner, in charge of the procedure. Version 1 is closer in spirit to US Chapter 11; version 2 is closer in spirit to UK Administrative Receivership or UK Administration. (It also bears a resemblance to old US Chapter X.) If the proposal were to be adopted, the version appropriate for a particular country would depend on that country's institutional structure and legal traditions. (Mixtures of versions 1 and 2 are also possible.)

Version 1

At the outset, after the company has declared (or been pushed into) bankruptcy, the company's debts are cancelled. The company's creditors do not go away empty-handed, however; as described in task B below, they will typically become significant shareholders. What matters is that the company starts out life in bankruptcy as a ‘new’, all-equity company.

An individual—a judge, say—is appointed to supervise the process. The judge has two immediate tasks: (A) soliciting cash and noncash bids for the new all-equity company; and (B) allocating rights to the shares in this company. These tasks could be carried out in parallel and completed within a pre-specified period of time: three months might be reasonable.190

Task A: Soliciting bids.

The judge solicits bids for the company over a three-month period. However, in contrast to a standard

189However, the AHM procedure does not avoid disputes over the amounts and seniorities of claims. Judges and the courts would have an important role in resolving these disputes under the procedure, just as they currently do.

190The procedure does not depend on this particular time horizon, and adjustments might be desirable.

7. BANKRUPTCY PROCEDURE |

171 |

auction, individuals can make cash or noncash bids for the company. In a noncash bid, someone would offer securities in the post-bankruptcy company instead of cash; thus, a noncash bid embraces the possibility of reorganization and/or recapitalization of the company as a going concern. The following are some examples of a noncash bid:

1.The old managers propose to keep their jobs, and offer claimants a share in the post-bankruptcy company.

2.The same financial arrangement might be offered by a new management team.

3.The managers of another company might propose to buy the bankrupt company, offering shares in their company as payment.

4.Management (old or new) might induce some debt in the company's capital structure. One way to do this would be to arrange for a bank to lend money to the post-bankruptcy company (the loan is conditional on the bid succeeding), and offer claimants a combination of cash and equity in the (levered) company. Another way would be to offer claimants a combination of shares and bonds in the post-bankruptcy company.

Note that, for the bidding process to work well, it is important that potential bidders have reasonably accurate information about the company's prospects. Part of the bankruptcy judge's job will therefore be to ensure that (serious) bidders have access to the company's books during the three-month bid solicitation process.

Task B: Allocating rights.

Before the judge can allocate rights to the shares of the new (all-equity) company, he must first determine who the company's claimants are and what are the amounts and priorities of their claims. This is a difficult job, which must be carried out currently in bankruptcy. The procedure envisages no changes regarding how this job is carried out.

Thus, it is supposed that the judge's deliberations lead to the identification of n classes of creditors who are owed (in total) the amounts D1, . . . , Dn, respectively, with class 1 having the most senior claim, class 2 the next most senior claim, and so on. The company's shareholders form the (n+1)th class, with a claim junior to all others.

172 |

II. UNDERSTANDING FINANCIAL STRUCTURE |

Having identified these classes, the judge can proceed to allocate rights to shares in the new (all-equity) company. If the ‘true’ value, V, of the company were publicly known (i.e. were verifiable), then it would be easy to figure out the total (monetary) share each class i is entitled to, based on absolute priority. Unfortunately, the value of a noncash bid is not objectively known. (This is why there is so much haggling in Chapter 11.) Therefore in order to allocate shares the procedure adopts an approach due to Bebchuk (1988). The nice feature of Bebchuk's approach is that it achieves absolute priority in spite of the fact that V is not objectively known.

Bebchuk's approach is to allocate equity to senior creditors and options to buy equity to junior creditors. To be precise, the most senior class (class 1) is allocated 100 per cent of the company's equity. (So if an individual creditor in that class is owed d1, she receives a fraction d1/D1 of the company's shares.) However, investors in the next most senior class (class 2) are given the option to buy the equity from the class 1 creditors for D1 per 100 per cent—that is, for the amount class 1 is owed. (So if an individual creditor in class 2 is owed d2, she receives an option to buy (up to) a fraction d2/D2 of the company's shares for a price of (d2/D2)D1.) Similarly, class i investors (3≤i≤n) have the option to buy equity from creditors senior to them at a price of (D1+D2+. . .+Di−1) per 100 per cent. Finally, shareholders (class (n+1)) are given the option to buy equity at a price of (D1+. . .+Dn) per 100 per cent. (Note that the rules of the procedure require senior claimants to relinquish their shares if they are bought out; they cannot hold on.)

The following example may clarify the allocation process. Suppose that n=2, and that there are five senior creditors each owed 200, ten junior creditors each owed 200, and 100 equal former shareholders, each of whom owned one share. Then in the ‘new’ company each senior creditor would receive 20 shares. Also, each junior creditor would be given an option to buy up to ten shares at 10 a share. (If all junior creditors exercised their options, the senior creditors would be bought out for 1,000.) And each shareholder would be given the option to buy one share for 30. (If all shareholders exercised their options, the junior and senior creditors would be bought out for 3,000.)191

191Notice that it is not necessary that all option-holders behave in the same way. For instance, suppose that one junior creditor exercises her option to buy ten shares for 100 (nobody else exercises an option). Then her 100 is used to buy 10% of each senior creditor's equity. Senior creditors are left with 90% of the equity and the junior creditor now has 10%. To take another example, suppose one shareholder exercises his option to buy a share for 30. (No other shareholder and no junior creditor exercise options.) First, 20 of this 30 is used to buy 1% of the options from each junior creditor, and then 10 is used to buy 1% of the shares from each senior creditor. The senior creditors end up with 99% of the equity and the shareholder has 1%. For more on this, see Bebchuk (1988).

7. BANKRUPTCY PROCEDURE |

173 |

This completes the judge's second task, task B.

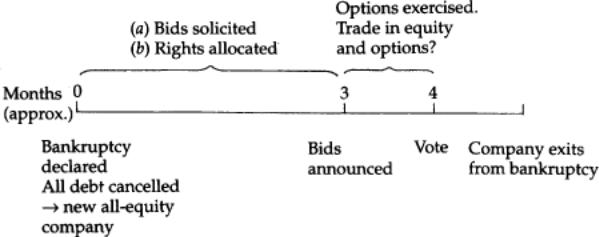

Once the three months are up, the judge reveals the bids arising from task A, and everyone can make an assessment of their worth (possibly with the help of some outside expert, such as an investment bank; claimants are, however, free to ignore any advice given). At this point, option-holders are given some period of time—a further month, say—to exercise their options. During this period there can be a market in equity and options, although the process does not depend on this.

At the end of this fourth month, some options will have been exercised and other will not. (The ones not exercised lapse.) The final step in the process is that the company's equity-holders (that is, those people who hold equity in the company at the end of month 4) vote on which of the various cash and noncash bids to select. (Voting is on the basis of one share–one vote; see below.) Once the vote is completed, the winning bid is implemented and the company emerges from the bankruptcy process.

The sequence of events is summarized in Figure 7.1. Note that Fig. 7.1

174 |

II. UNDERSTANDING FINANCIAL STRUCTURE |

at the time of the vote all claimholders' interests are (roughly) aligned. Whether those voting are former creditors or former shareholders (who have bought out the creditors), they are now all shareholders and have an incentive to vote for the highest-value bid.

It is worth returning to the numerical example to understand the interplay between the bids and the options. Suppose that after month 3 the best bid is perceived to value the company at less than 1,000. Then no one will want to exercise their options (the junior creditors will not want to spend 1,000 to get something worth less, and, a fortiori, the former shareholders will not want to spend 3,000), and the senior creditors will end up with all the equity. Suppose next that the best bid is perceived to be worth more than 1,000, but less than 3,000. Then the junior creditors will choose to buy out the senior creditors, but the former shareholders will not want to exercise their options. Finally, if the best bid is perceived to be worth more than 3,000, then the shareholders will buy out both classes of creditors.

It should be clear from this example how options preserve the absolute priority of claims even though there is no objective valuation of the company.

In version 1 the judge's role in the bankruptcy procedure is supervisory. He is in charge of the bankruptcy process, but he does not run the company during bankruptcy—in fact, this job will probably be left in the hands of incumbent management. (The judge may be required to approve major investment and financing decisions, as in US Chapter 11.) In version 2, however, the supervisor of the process is given a more major role.

Version 2

Version 2 differs from version 1 in two principal ways.192 First, secured debt is left in place. Second, the supervisor of the bankruptcy process takes on the job of running the company for a period of time.

Treatment of Secured Debt.

In version 1, all debt is converted into equity (secured and unsecured). This is attractive because it clears

192 Version 2 is based on Aghion et al. (1995).

7. BANKRUPTCY PROCEDURE |

175 |

up the balance sheet. But it has the disadvantage that creditors receive a security that they may not really want to hold. In version 2 only unsecured debt is converted into equity: secured debt is left in place. That is, when bankruptcy commences, an appraisal is made of the collateral underlying each secured claim. If the appraised value is found to be more than the secured creditor's debt, then the debt is left in place. If it is found to be less, then only the secured portion of the debt is left in place; the residual is treated in the same way as unsecured claims; that is, it is converted into equity.193

Note that this ‘minimal’ debt–equity swap has the desirable property that it turns the company into a solvent one. (Of course, a complete debt–equity swap has the same virtue.) The reason is that one can be confident that the value of the company is at least as great as the sum of the appraised values of its physical assets. However, one cannot a priori judge the value of the remainder of the company—that is, the more nebulous going-concern value. Accordingly, in version 2, as in version 1, all unsecured debt is converted into equity. (In version 2, the most senior (unsecured) creditors receive equity directly, while subordinated creditors and former shareholders receive options to buy equity.)

Role of the Bankruptcy Practitioner.

In version 2, it is supposed that the bankruptcy practitioner actually runs the company during the four months that the procedure lasts. That is, she replaces incumbent management—or, more precisely, the board of directors. (She can, however, retain certain inside directors/managers, if she wishes.)

193In contrast, in version 1 secured debt is treated just like any other senior debt; i.e., it is converted into equity. To be more precise, in version 1 a secured creditor's collateral is appraised. If the appraised value is greater than the debt, then the creditor is treated as if all her debt is senior (so she receives shares). If the appraised value is less than the debt, the creditor is treated as if she has a mix of senior and junior debt (so she receives a mixture of shares and options). In both versions 1 and 2, it is envisaged that secured creditors will not have the right to seize collateralized property (unless this property can be shown to be unnecessary to the company's reorganization). The reason is that seizure could lead to an inefficient dismantlement of the company's assets through a ‘me-first’ grab. (Note that this is also the position taken by current US bankruptcy

law; see Baird 1992: § 8C.) However, it seems reasonable in version 2 to allow a secured creditor to seize her collateral after the four-month bankruptcy period is over if the company remains in default vis-à-vis this creditor.

176 |

II. UNDERSTANDING FINANCIAL STRUCTURE |

The bankruptcy practitioner has two main duties. First, she has a general obligation to act in the interest of shareholders and option-holders combined, that is, to maximize the value of the company during her term of office.194 Second, she is obliged to draw up a plan (or plans) for the future of the company, to be presented to shareholders at the end of month 3 (before the options are exercised).195 No restrictions are put on the nature of the plan. For example, the plan might be to reorganize the company—maybe with new management and/or a new financial structure (in which case shareholders would receive new securities in the company); to sell it as a going concern; or to close the company down and sell off its assets piecemeal. In fact, a plan is just like a cash or noncash bid. The plan is put to a shareholders' meeting at the end of month 4 (after the options are exercised) and is implemented as long as it receives majority approval. (The bankruptcy practitioner may choose to put more than one plan to shareholders and see which one receives greatest support.)

An important difference from version 1 is that a formal auction is dispensed with. The bankruptcy practitioner may hold one if she believes this would increase value, but she is not obliged to do so.196 Similarly, the practitioner has discretion about who should have access to the company's books and—if bids are made—which bids should be presented to shareholders. In this respect, the practitioner is in a similar position to the board of directors of a solvent company that is thinking of selling it.

In version 2, the bankruptcy practitioner would also have the authority to take other actions. For example, she could sell some or even all of the company's (unsecured) assets before month 3 if she deemed it necessary to do so. (This might be important in cases where uncertainty about the company's future threatened the customer or supplier base.) In addition, she would have the authority to raise new capital or to release cash from the business.

194This could be formalized in two ways. First, a fiduciary duty towards shareholders and option-holders could be imposed on the bankruptcy practitioner. Second, the practitioner could be put on an incentive scheme.

195The bankruptcy practitioner would be paid out of company funds in the same way that a receiver or administrator is paid under current UK insolvency law.

196In some situations, an open auction might allow rivals to learn sensitive information about the company's operations or plans, which could reduce the company's value in the long run.

7. BANKRUPTCY PROCEDURE |

177 |

For example, she might use profit earned by the business or cash from asset sales to pay off (secured) creditors or to pay out a dividend to the (new) shareholders. (In the latter case, the option exercise price for junior claimants would be reduced accordingly.)197

The bankruptcy practitioner's appointment is obviously an important issue in version 2, given the power of the position. In many cases a large (senior) creditor is in the best position to make the appointment. For example, in the UK a senior creditor—usually a bank—often negotiates as part of its debt contract the right to appoint a ‘receiver’. (This right is embodied in what is called a ‘floating charge’.) It might make sense for such a creditor also to appoint the bankruptcy practitioner in version 2 of our procedure. A similar arrangement might be used in Germany or Japan, where companies often have a ‘lead bank’ as a significant creditor.198 In other cases, when there is no natural large creditor the appointment might be made by the court.

Note that, once appointed, the practitioner has a responsibility to all shareholders (not just the person making the appointment). This raises the question of who has the authority to remove the practitioner if she is doing a bad job. Prior to month 4, it probably makes most sense to leave this decision in the hands of the court, with action being taken only when a majority of each class of claimants has expressed dissatisfaction. The point is that, until the ownership of shares has been settled, it is not clear whom the practitioner is representing, and so she should have a degree of security and a broad remit to ‘maximize the value of the company’. Another possibility, however, is to give shareholders the power to dismiss the practitioner from the beginning. The disadvantage of this is that new shareholders may push the practitioner towards a quick sale of the company: they know that if good news arrives within the four months they will be bought out by the option-holders, whereas if bad new comes in they will be

197An obvious danger with giving the practitioner so much discretion is that she may abuse her power. For example, the practitioner, hoping to extend her term of office past month 4, might engage in empire-building activities. Note, however, that the practitioner could be required to obtain majority approval from shareholders for an extension, which would reduce the likelihood of this kind of self-interested behaviour.

198For a discussion of the possible role of lead banks in bankruptcy procedure, see Aoki (1994).

178 |

II. UNDERSTANDING FINANCIAL STRUCTURE |

left holding equity and so they prefer to avoid uncertainty. (This is the same phenomenon as described in example 1 of Section 3.)

5.An Assessment

Consider how well the AHM procedure satisfies the three goals of a bankruptcy procedure discussed earlier. Arguably, the AHM procedure does a reasonable job of meeting goal 1: since the new owners decide the future of the company, they have an incentive to vote for an efficient outcome. Also, the procedure preserves the ex ante bonding role of debt (goal 2). In particular, since shareholders may accept a bid or plan involving another management team, managers' jobs are at risk. However, managers have the opportunity to convince shareholders that the bankruptcy was not their fault and that they should be retained. In this respect, bankruptcy is arguably not so harsh that managers will avoid it at any cost.

Note also that the procedure could be modified to be softer or harder on incumbent management (at some probable cost in terms of ex post inefficiency) if that were thought to be desirable. For example, in version 1 incumbent management could be favoured by handicapping other bidders in the auction; for example, the auction rules could state that an outside bidder has to win more than two-thirds of the votes. (Another way to soften the blow of bankruptcy in both versions 1 and 2 is to give managers a ‘golden handshake’ (or ‘parachute’) in the form of senior debt in their company.) Conversely, management could be disfavoured in version 1 by a requirement that they must win more than two-thirds of the votes to retain their jobs.

Finally, the option scheme ensures that absolute priority (goal 3) is met (as long as junior claimants have enough cash to exercise their options; this is discussed further below).199

199 At the same time that the AHM proposal was being developed, two other proposals for bankruptcy reform appeared in the literature: Adler (1993) and Bradley and Rosenzweig (1992) (see also Adler 1994). These proposals, like the AHM one, envisage that when a company goes bankrupt the company's equity is transferred to creditors. Adler's proposal removes the right of individual creditors to foreclose on a bankrupt company's assets while Bradley and Rosenzweig's does not. In both proposals, the company's debt is not accelerated and no bids are solicited. Also, while both proposals envisage that the transfer of control to creditors will bring about improved management, neither is very explicit about how this will happen.

7. BANKRUPTCY PROCEDURE |

179 |

It is worth returning to examples 1 and 2 to see how the AHM procedure compares with a structured bargaining procedure like US Chapter 11.

In example 1 there are two alternatives: liquidate for 90, or keep the company going for an average value of 110. The big difference between the AHM procedure and structured bargaining is that, if the former creditors as shareholders get to vote, they will choose to keep the company going, since they enjoy all of the potential upside gains from continuation. Of course, in this instance the former shareholders will be eager to exercise their options, since by spending 1 they obtain a share worth 1.1. (Junior creditors are being ignored.) In other words, the former creditors will get paid their 100 in full by the former shareholders, and the former shareholders, as residual claimants, will vote to maintain the company as a going concern. A good company has been saved.

In example 2, the alternatives are to liquidate for 90 or keep the company going for an average value of 80. Here, the former shareholders will not exercise their options, and the former creditors—as the new shareholders—will vote to liquidate and receive 90. A bad company has been shut down.

Notice that problems 1 and 2 have been resolved without eliminating the possibility of reorganization. In example 1, incumbent managers are able to retain their jobs even though they may not have the cash in hand, and any incentive on the part of the creditors to liquidate the company prematurely is avoided. In example 2, managers are rightly unable to keep their jobs. In neither example is there room for haggling. And in both examples the people who end up voting over the future of the company are the residual claimants (i.e. those who bear the consequences of their actions); as a result, the final outcome is the value-maximizing choice.

6.Further Considerations

This section briefly raises some additional issues and discusses a number of practical problems that might arise under the AHM procedure.