Учебный год 22-23 / William_Simons_Private_and_Civil_Law_in_the_R

.pdfxx |

William Simons |

Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika cannot be underestimated—especially in light of the hindsight which the post-Soviet era affords us. Feldbrugge has offered his view of this period, again to a wide community, in a work entitled: The Perestroika Jig-Saw Puzzle: Observations of NATO’s Sovietologist- in-Residence 1987-1989 (Leiden 2003).

Furthermore, for many years, Professor Feldbrugge has been a member of The Netherlands Council for Peace and Security (initially, the Adviesraad Vrede en Veiligheid and, later, the Commissie Vrede en Veiligheid van de Adviesraad Internationale Vraagstukken).

(C) The third major activity has been the Russian-Dutch collaborative effort invlolving the new Russian Civil Code highlighted above.This has hadanimpactuponscholarshipanduponsocietyassignificantashisIC- CEESandNATOengagements—and,ultimatelyperhaps,anevengreater one (if such things can at all be accurately measured).8

Undoubtedly, the new RF Civil Code could have been prepared without any foreign assistance whatsoever; alternatively, such assistance could have provided by one or two major players. Indeed, German and North American thinkers, for example, have also contributed to the elaborationofRussia’snew“EconomicConstitution”.9 These other initiatives notwithstanding, the Dutch-Russian undertaking has had an impact upon the rebuilding of civil law in post-Soviet Russia which is out of all proportion to the relationship which the territories of The Netherlands and Russian Federation bear to one another in size, for example. Without

Feldbrugge’s initiative and vision, this unique collaborative effort might never have come into being or, at best, might have been a much less successful project than, in fact, has been the case.

And “as one good thing often leads to another”, the bilateral cooperation begun by the Institute with Russia (and also, during the same period, with Kazakhstan, Belorussia and Ukraine) provided the basis for another

8This project has also resulted in a translation into Russian of several books of the new Dutch Civil Code (F.J.M. Feldbrugge, (ed.), Grazhdanskii Kodeks Niderlandov,

Leiden 1996 (second edition, Leiden 2000), 372 pps.) and into English of the first book of the RF Civil Code (G.P. van den Berg and W.B. Simons, “The Civil Code of the Russian Federation, First Part”, 21 Review of Central and East European Law

1995 Nos.3-4, 259-426). One of Feldbrugge’s most recent works also deals with the RF/NLcollaboration;seeF.Feldbrugge,“TheCodificationProcessofRussianCivil

Law”, J. Arnscheidt, B. van de Rooij and J.M. Otto, (eds.), Lawmaking and Development: Explorations into theTheory and Practive of International Legislative Projects, Leiden 2008, 231-244.

9Professor Alekseev, former chairperson of the USSR Committee of Constitutional Supervision (the forerunner of the RF Constitutional Court), for example, has often referredtotheCivilCodeasRussia’s“economicconstitution”;see,e.g., “Misiia Rossiiskoi nauki”, Iurist December 2000 No.49, 2.

Introduction |

xxi |

major project in the 1990s/2000s: consideration of the harmonization of private law in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). This has resulted, in turn, in a CIS Model Civil Code (as well as several other pieces of CIS model legislation).10

* * *

This sketch—of selected highlights of the accomplishments of Profes- sor Feldbrugge—is accompanied by photographic images reproduced below. They help to round out this overview of his professional service and achievements.

However, it would not be a complete overview if I were to neglect to touch upon his personal side. Yet I shall do so here only in brief since he is a very modest person. The consideration, which Professor Feldbrugge has consistently shown for the needs and thoughts of others, is a part of his professional dedication; but, it is also intertwined with his gentle interpersonal skills. The numerous colleagues who have been visitors to theFeldbruggehomeinZundert—andhavepartakenofthewarmhospi- tality which his spouse Máire and he always offer to their guests—know this well. So do the many others in the field who have had to pleasure to become acquainted with him in person in other venues.

This volume has been long in coming; he knows that quite well.Yet time has not diminished in any way the measure of his dedication to the field or the significance of his works to its students in the broadest sense of the word. This volume is offered to him by many with the highest professional regard and warm personal greetings which the intervening time between the conferences and the appearance of this volume in print has also failed to diminish. The picture below on page xxx from the 2003 Conference is part of this same expression in another form.

IV. The 2003 Conference Topic. The public-private distinction, as has been mentioned above, was the theme selected for the 2003 Leiden convocation. The prior two Leiden conference topics dealt with the (re) generation of private law and its impact upon legal practice and comparative law scholarship; this third theme obviously rounds out the circle.

10At least as far as model “law in books” is concerned (recalling Roscoe Pound’s early twentieth century paper which began with this phrase), this has put the CIS— otherwise often viewed skeptically from afar—ahead of the EU in this particular field. See, e.g., William B. Simons, “The Commonwealth of Independent States and Legal Reform: The Harmonisation of Private Law”, Law in Transition 2000 (Spring), 14 et seq. reproduced at <http://www.ebrd.com/pubs/legal/lit001a.pdf>.

xxii |

William Simons |

(A) It is also to state the obvious to remark that the public sector outweighed the private sector, in all of its aspects, in the Soviet Union and, similarly, in the realms of its Eastern European “little brothers”; in fact, the public-private distinction had—one could quip: according to the plan— virtually been erased during most of the Soviet period. When the public sector had engulfed things private in the Soviet Union and its Soviet Bloc, there was no great need to consider such a distinction.

However, since the beginning of the 1990s, the private sector has become an element of enormous positive interest in post-Soviet Russia and the CIS (and, even earlier, in most of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe). Yet, (certainly in Russia) the swing to “the right” in the early 1990s seemed to be as sharp as the swing in the opposite direction had been in 1917. Then, for example, there had been several mechanisms used to push society across the 1917 bridge to the bright shining future (most k svetlomu budushchemu). One was the nationalization of private property. In the 1990s and 2000s, it has been the reverse process—the privatization of state property—which forms one of the major levers of change. The state would take several giant steps in retreat from the all-encompassing public sector; in doing so, it would turn over a great share of its attention to economic and social matters to the private sector; it would step down from most of the commanding heights. All power to privatization!

Yet, once private law began to be revitalized in the post-Soviet era, elementary questions began to arise: would this radical shift accentuate a public-private distinction (as newly rich citizens sought to push the state away from their personal treasures); or, on the other hand, when things were more in balance, would such a theoretical distinction lose its importance in practice? After all, a prime factor in the Soviet “experiment” had been the general continental European concern for social issues (typified, for example, by Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum). In the 1990s and 2000s, this concern—enhanced inter alia by a century of dealing with the effects of world military conflicts—might lead to a blurring of this distinction rather than to its sharpening.

Ideas from other other sources have also inspired the choice of this topic for the last Leiden conference: (a) B.B. Cherepakhin’s 1926 work11

(devoted to the public/private distinction in an earlier transition period of Russian history); (b) conference proceedings from the 1980s devoted to the public/private distinction in the United States12 and (c) a white paper ofTheNetherlandsScientificCouncilforGovernmentPolicy(discussing

11“K voprosu o chastnom i publichnom prave”, in Uchenye zapiski Gos. Saratovskogo Universiteta, Tom II, Vypusk 4, Saratov 1924. I am indebted to Dr. Mikhail V. Gorbunov for bringing this source to my attention.

12130 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 1982 No.6.

Introduction |

xxiii |

the divisions between public and private responsibilities at the end of the twentieth century).13

(B) The origins of the public/private dichotomy in the fields of political and legal thought have been termed a “double movement” by Harvard legal historian Morton Horwitz. On the one hand, there was the idea of a distinct public realm which began to take shape along with the development of nation-states and theories of sovereignty in the sixteenth and seventeenthcenturies.Ontheotherhand,asstateleaders(firstthecrown and, thereafter, people’s assemblies) began to (re)assert broad powers for imposing their will upon society, the notion of a private sector began to take shape: the creation of a “space” separate (and protected) from the strong arm of state power.

In the nineteenth century, wealth increased along with empires and (inter)national connections as a result of advancing media and expanding economic intercourse.14 The lines of battle in the public versus private struggles of that era seemed to increase in number and the skirmishes becamefiercerinnature.Theywereeconomicallyandpolitically—aswell associallyandlegally—charged.Thishelpedtoproduce,forexample,the vision (or was it propaganda?) of the self-regulating market; as Polanyi wrote,15 this had become the “fount and matrix” of nineteenth century civilization.

At the beginning of the next century, two countries which had been engulfed by these events formed the main stage for crucial developments in the public/private saga; but these marked tracks diverging into the future from what largely had been a common strand of nineteenth-century thoughtandassociatedaction.In1905,Russiaunderwentitsfirstrevolution while the US Supreme Court rendered a decision of crucial importance for the private/public distinction in early twentieth century America. In little more than a decade, the Russian path would lead to a system where only the public sector mattered. On the free market range of the US, after the 1905 Lochner decision,16 the public sector was pushed even further into retreat from a position where it had already been marginal to say the least.Indeed,bythistime,theeffectsofsocialDarwinism—propounded so forcefully by disciples of Herbert Spencer—had already led many Pro- gressives and other like-minded US citizens to argue that the social scales

13W. Derksen, M. Ekelenkamp, F.J.P.M. Hoefnagel, W. Scheltema, (eds.), Over publieke en private verantwoordelijkheden, reproduced at <http://www.wrr.nl/content. jsp?objectid=2658>.

14See Eric Hobsbawm, Age of Empire: 1875-1914, New York 1989.

15Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation, New York 1944. I am grateful to Dr. Hans Oversloot for bringing this source to my attention.

16Lochner v. People of State of New York 198 US 45 (1905).

xxiv |

William Simons |

requiredafairerbalanceandthatthiscouldonlybyachievedthereasoned state regulation of private economic activity in the public interest.

But at that point in US history, the road taken was a different one: freedom of contract in the US had been constitutionalized by Lochner. This further enlarged the private sector and demonized state economic regulation. Thus—despite an increasingly progressive US legal commu- nity, whose writings were to be seen in the school of legal realism joining members of the judiciary (such as Brandeis and Cardozo) with scholars (such as Cohen, Corbin, Hohfeld, Llewelyn, and Pound)17—it took three more decades before the Supreme Court proclaimed the United States to be a jurisdiction where not only the private sector seemed to matter.18

And then things seemed to move forward quite quickly:

“By 1940, it was a sign of legal sophistication to understand the arbitrariness of the division of law into the public and private realms [and no] advanced legal thinker of that period, I am certain, would have predicted that forty years later the public/private dichotomy would still be alive and, if anything, growing in influence […].”19

This is not the place to dwell further on the birth, growth and future of the public/private distinction in Russia or to comment in depth on the differences in the earlier Russian approach (taking to the barricades) and its faint US equivalent (debating in society and arguing in courtrooms). These differences of course have meant that the Russian experience in recent years started at the opposite end of the spectrum from the US

17See, e.g., William W. Fisher, III, Morton J. Horwitz, Thomas Reed, American Legal Realism, Oxford 1993.

18West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish 300 US 379 (1937) constitutionalized the non-arbitrary state regulation of economic activity. Of course, groundbreaking US legislation— attempting to rectify some of the worst abuses of economic power in the private corporate sector—had been enacted as early as 1890. In fact, passage of the 1890

ShermanAntitrustAct had been brought about, in part, by Senator Sherman rallying his colleagues to his side by using the tool of fear of worse things to come (if his bill were not enacted): under “the socialists, the communists and the nihilists” (Congressional Record-Senate, 21 March 1890, “Trusts and Combinations”, sec.2460, para.4). (I am grateful to Professor John Quigley for his help in retrieving this source.) Sena- tor Robert LaFollette had called this and similar legislation “the first efforts […] to reassert the power of popular government and to grapple with these mighty private interests” and “the strongest, most perfect weapon”. Robert M. LaFollette, LaFollette’s Autobiography, Madison, Milwaukee, London 1968, 40 and 309 respectively.

19Morton J. Horwitz, “The History of the Public/Private Distinction”, University of Pennsylvania Law Review, op.cit. note 12, 1426. Only a few of the many US cases illustrating this dichotomy are: Shelly v. Kraemer 334 US 1 (1948), Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka 347 US 483 (1954), and Kelo et al. v. City of New London et al. 545 US 469 (2005). Cases from the RF Constitutional Court with which these can be compared are: Interest Rates (1999), Tver Spinning Plant (2000), and Credit Organizations (2001).

Introduction |

xxv |

example: in Russia, it has been the art of the state in retreat—not taking state power forward. The latter was the battle which Fighting Bob LaFollette and like-minded thinkers waged for decades against the extremes of a minimally-regulated capitalist Wild West. The Russian problem was the over-regulated Soviet East. And thus, the main thrust of political, economic, and legal thinking at the end of the twentieth century––both in the new Russia as well as other parts of the CIS/CEE regions––has also been radically different from that, for example, in the US: it has been engagedinamajor(re)definitionofapreviouslyminimalist(non-existent) private sector, the (re)emergence of private law and promulgation inter alia of market-oriented constitutions and civil codes.20

The advanced legal thinker of whom Horwitz wrote would certainly continue to be amazed about the growth of the public/private dichotomy in the US; but she would also, undoubtedly, experience similar amazement about its appearance in Russia. While obviously the United States is not the only country with which to compare Russia (certainly not vice versa?),21 it seems to me that this two-country perspective can be useful.

Horwitz also wrote about a second strand of related thinking. This was not, however, as much about the blurring of the distinction between public and private as it was about the supremacy of one above the other; e.g., about Progressives in the US in the first part of theXXcentury who had put their faith in the public above the private. But he went on to observe that the revival of natural-rights individualism—after the end of

20There have also been major reforms in other parts of the public law arena, such the promulgation of new criminal codes and codes of criminal procedure. But our focus is on private law; thus, I shall limit my excursion into neighbouring territory with this minimalist remark and two citations: William Burnham, “The New Russian Criminal Code: A Window Onto Democratic Russia”, 26 Review of Central and East European Law 2000No.4,365-424;andWilliamBurnhamandJeffreyKahn,“Russia’s

Criminal Procedure Code FiveYears Out”, 33 Review of Central and East European Law 2008 No.1, 1-93.

21The comparison of countries (at least these days) seems sooner or later to lead to an “abnormal/normal country” debate; this certainly has been the case in the case of RF and the US. Perhaps this is because of holdover thinking from the Cold War, the big country syndrome, or the natural reaction to “the other”. So, when comparing Russia to the US, Russia is usually seen as not normal. But, there are those outside Russia who argue that Russia can be characterized as a normal country when viewed among a different group of countries; see Andrei Shleifer and Daniel Treisman, “A

Normal Country: Russia after Communism”, 19 The Journal of Economic Perspectives

2005No.1,151-174and“AndreiPerla:Normal’naiastrana”,25June2008,reproduced at <http://www.vz.ru/columns/2008/6/25/180178.html>). I am grateful to Dr. Tatiana Borisova for bringing these sources to my attention.

xxvi |

William Simons |

the SecondWorldWar—meant “the collapse of a belief in a distinctively public realm standing above private self-interest”.22

In Russia, so many changes have occurred in the post-1991 period that it is difficult to come to a single, hard conclusion about things there.

But the public realm in the 2000s in Russia certainly has not collapsed although the swift Russian shift in the early 1990s from an administrative- command economy to a market-type model did offer zealots of the latter the chance to begin engineering their own version of the Lochner era: all power to the capitalists!23

Of course, the public/private distinction continues to be of (legal) interest in jurisdictions outside the bipolar RF/US world (e.g., the constitutionalization of private law in the EU): how should state action (in its various guises) be delineated from that of private actors; when should a particular (rigorous) standard of conduct for the state also be applied to seemingly private acts?

The public/private distinction brings with it a (much) more complex bundle of factors than can be reflected in such simple ideological bright- lines as nationalization versus privatization—althoughthisishowitisoften presented in the popular media as well as in some branches of scholarship. As one ponders the issue more carefully, it seems to become a matrix:

Centralization versus decentralization (Petrazhitskii as cited by Cherepakhin24);

Unity or singleness (Bagehot, Austin) versus plurality (Laski).

* * *

Thechaptersinthisvolumeareintendedtofacilitatethereader’sfurther charting of the progress made in Russia (and the region) in the revitalization of private and civil law—and its impact upon practice and comparative legal studies—and appreciating the role which the distinction between the public and private sectors is seen as playing in the process.

22Horwitz, op.cit. note 19, 1427.

23Rilka Dragneva and I have looked at a number of RF Constitutional Court cases to determine whether post-Soviet Russia was gearing up its own Lochner-style cycle. Thecasesshowadifferentpath.See“Rights, Contracts, and Constitutional Courts: The Experience of Russia”, in Ferdinand Feldbrugge and William B. Simons, (eds.),

Human Rights in Russia and Eastern Europe: Essays in Honor of Ger P. van den Berg, in William B. Simons, (ed.), Law in Eastern Europe, No.51, The Hague, London, Boston 2002, 35-63.Also published in Russian as: “Prava, Dogovory i Konstitutsionnye Sudy: Opyt Rossii”, 3 Tsivilisticheskie Zapiski, Essays in Honor of Sergei SergeevichAlekseev, Moskva, Ekaterinburg 2004, 406-440.

24Cherepakhin, op.cit. note 11.

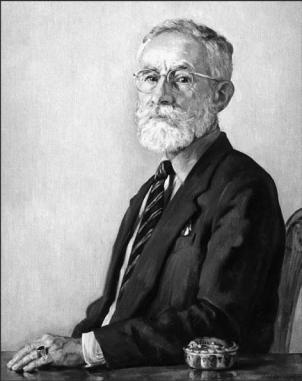

Photographic reproduction of a portrait of Professor Ferdinand Feldbrugge

by Leendert van Dijk (1998).

xxviii |

Private and Civil Law in the Russian Federation |

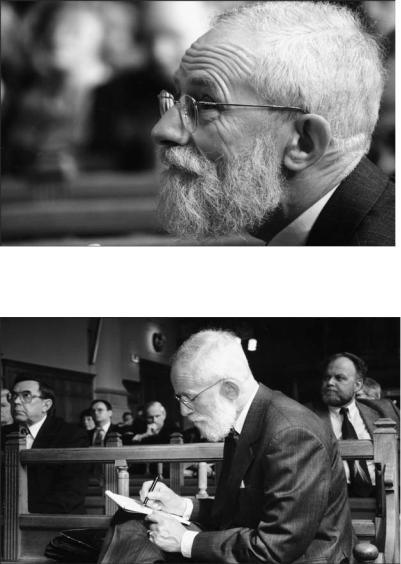

At the behest of Queen Beatrix, Ferdinand Feldbrugge was made a Knight in the Order of The Netherlands Lion

(Ridder in de Orde van de Nederlandse Leeuw) on 26 September 2003.

Photographs |

xxix |

Ferdinand Feldbrugge at the 1998 Leiden Conference. Also visible in the lower photograph are

Chief Justice V.F. Iakovlev (ret.) and Dr. M.V. Gorbunov (left and right, respectively).