Essentials of Orthopedic Surgery, third edition / 14-Answers to Questions

.pdf

Case Studies

Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

WILLIAM C. LAUERMAN

History

E.D. is a 72-year-old woman with a 2-year history of progressively worsening back pain, with radiation of pain into the buttocks, posterior thighs, and more recently into her legs bilaterally. The pain is worse with walking and is relieved when she stops to sit down. She denies any bowel or bladder changes. She notes that it is significantly easier walking in a grocery store pushing a cart than it is to walk in a mall. Her past medical history is positive for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Past medical history, family history, and social history are otherwise unremarkable. Review of systems is noncontributory.

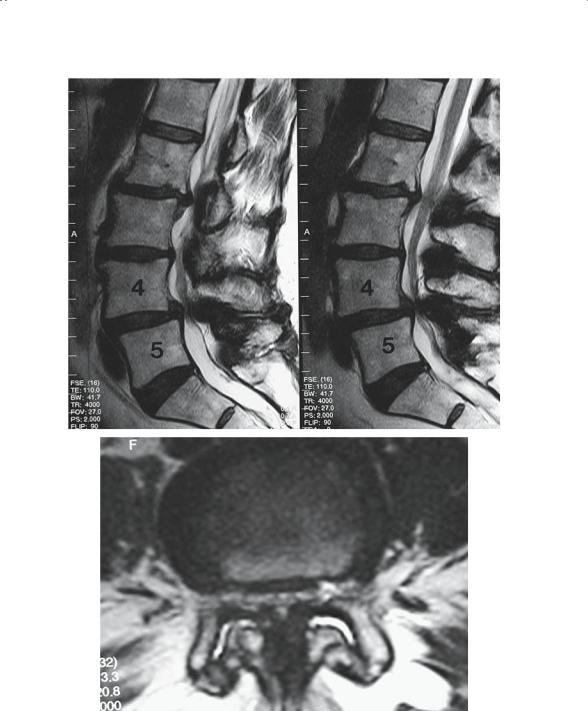

On physical examination, she has a normal gait. She tends to stand in a forward flexed position, and she has limited extension of the lumbar spine, with pain on extension. Pulses are palpable in both feet. Neurologic examination demonstrates normal motor and sensory function. Her deep tendon reflexes are symmetrically diminished at the knee and ankle. Her toes are down-going. Straight leg raising is negative. (See Figs. 1, 2.)

Treatment

The patient had previously been treated with physical therapy, including Williams flexion exercises, which improved her symptoms for several months but did not give her long-lasting or adequate relief. She underwent a trial of lumbar epidural steroids. Each injection led to good relief of her symptoms but that relief lasted only 2 to 3 weeks. Having failed nonoperative treatment, she elected surgery and underwent a decompressive laminectomy at L4–L5 with posterolateral fusion, utilizing pedicle screw instrumentation and iliac crest autograft. (See Fig. 3.)

527

528 W.C. Lauerman

FIGURE 1. Lateral radiograph demonstrates a grade 1 degenerative spondylolisthesis at L4–L5.

Discussion

Degenerative spondylolisthesis is common and increases in prevalence with increasing age. It is more common in women than in men, in blacks than in whites, and is found with increased frequency in patients with diabetes. Degeneration of the disk and facet joints, most commonly at L4–L5, leads to anterior slippage of the cephalad vertebrae (L4 in this case) on the level below (L5). It is common to see spinal stenosis in association with degenerative spondylolisthesis, and this patient’s symptoms, including back pain and stiffness with aching pain into the buttocks, thighs, and legs, are common. A common complaint is pain with walking that is often relieved by stopping and sitting down. Patients frequently note that they can walk farther in a grocery store pushing a cart than they can in a mall.

In spinal stenosis, positions of flexion, such as pushing a grocery cart or sitting down, are more comfortable than extension, and the most common

Degenerative Spondylolisthesis |

529 |

A

B

FIGURE 2. Sagittal (A) and axial (B) magnetic resonance (MR) images. The sagittal view demonstrates the spondylolisthesis, as well as the significant thecal sac narrowing at L4–L5. The axial view demonstrates enlargement and arthritic change in the facet joints bilaterally, thickening of the ligament flavum, and severe central and lateral recess stenosis.

530 W.C. Lauerman

FIGURE 3. Decompressive laminectomy at L4–L5 with posterolateral fusion, utilizing pedicle screw instrumentation and iliac crest autograft.

physical finding is limited extension of the lumbar spine with pain on extension. Treatment options include nonoperative measures such as a daily back exercise regimen, flexion exercises, physical therapy modalities, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications, or epidural steroid injections. When nonoperative measures fail, surgery is often indicated, usually with good results. The primary goal of the surgical treatment of spinal stenosis is decompression of the affected nerve roots and/or thecal sac. In cases of degenerative spondylolisthesis, because of the risks of further slippage, concomitant fusion is routinely employed.

Hallux Valgus

SCOTT T. SAUER

History

A 52-year-old woman presents with worsening bilateral forefoot pain over the last three years. She describes pain in the left foot that is greater than the right foot. It is an achy, sometimes sharp intermittent pain over the medial aspect of both first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints. She rates the pain as 4 of 10 with 10 being the worst pain she has ever felt. The pain she feels is worse with shoe wear and walking and is relieved by wearing sandals. She also reports having to wear multiple layers of socks to keep her shoes from rubbing on the medial aspects of her forefeet. She describes no pain with arising, no swelling, no loss of sensation, no joint stiffness, and no flatfoot. Her past medical history is significant for breast cancer, for which she has had a mastectomy. Currently, the only medication she is taking is tamoxifen. She has no known drug allergies. She is a nonsmoker, and her review of systems is noncontributory.

Physical Examination

This is a well-developed, well-nourished female in no apparent distress. She is 5 feet 3 inches in height and weighs 118 pounds. She walks with a normal-appearing gait. Her station shows bilateral hallux valgus with normal-appearing arches and heels in slight valgus positioning. She is able to double-toe heel rise with minimal tenderness in her bilateral first MTP joints, plantar and medial. Examination of her right foot and ankle shows a moderate hallux valgus formation with a medial protuberance noted. No skin lesions or edema. Dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial artery pulses are palpable. There is tenderness to palpation over the medial and plantar medial aspect of the first MTP joint. There is no pain plantarly over the medial or lateral sesamoid, no lesser toe pain, and no medial midfoot or hindfoot pain. No ankle pain noted. Ankle range of motion is 5 degrees of dorsiflexion, 40 degrees of plantar flexion, 10 degrees of inversion, and

531

532 S.T. Sauer

5 degrees of eversion. First MTP joint range of motion is approximately 30 degrees of extension and 20 degrees of flexion with no ligamentous instability. Ankle dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, inversion, eversion, and toe extensor and flexion strength are 5/5. Sensation is intact on the dorsal, medial, lateral, and plantar aspects of the foot.

Examination of the left foot and ankle shows a moderate hallux valgus with protuberance medially noted. No skin lesions or edema noted. Dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial artery pulses are palpable. There is tenderness to palpation over the medial first MTP joint, as well as plantar medially in the same region. There is no sesamoid pain noted. No medial midfoot or hindfoot pain is noted. No ankle pain noted. Ankle range of motion is 5 degrees of dorsiflexion, 40 degrees of plantar flexion, 10 degrees of inversion, and 5 degrees eversion. First MTP joint range of motion is 30 to 40 degrees of extension and 20 degrees of flexion with no ligamentous instability noted. Ankle dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, inversion, eversion, and toe extension and flexion strength are 5/5. Sensation is intact in the dorsal, medial, lateral, and plantar aspects of the foot.

X-Rays

Weightbearing anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and mortise views of her bilateral feet show bilateral mild hallux valgus deformities with slight subluxation laterally of the sesamoids with congruent first MTP joints. Medial exostosis present. First MTP joint appears without degenerative change. First and second intermetatarsal (IM) angle on the left foot is 12 degrees with a hallux valgus angle of 20 to 25 degrees. No other bony abnormalities noted.

Treatment

Surgical correction of left hallux valgus using distal chevron bunionectomy, which includes distal metatarsal osteotomy with exostectomy and medial first MTP joint capsule tightening.

Discussion

This patient has a symptomatic hallux valgus deformity; the left foot is clinically worse than the right foot. Clinically, hallux valgus can be problematic in that it makes shoe wear difficult. With the progressive valgus deformity of the toe, extra strain is placed on the medial structures of the first MTP joint, and this area becomes more prominent. With shoe wear, the inner aspect of the shoe pushes on the medial aspect of the first MTP

Hallux Valgus |

533 |

joint, which can cause friction and pain. With this repetitive stress, as well as progression of the bunion deformity, bony buildup can occur on the medial aspect of the first metatarsal head; this perpetuates continued discomfort as the exostosis enlarges. As the bunion deformity progresses, it can affect the lesser toes, creating hammer toes, which have hyperextension at the MTP and DIP joints and hyperflexion of the PIP joints.

Treatment is aimed at relieving pain, which can be done conservatively and nonsurgically in early stages of hallux valgus by shoe wear modification utilizing a wider toe box to prevent rubbing or friction. Toe spacers, which keep the first toe in a straight orientation in relation to the other toes, can also be used, as well as physically altering the shoe with shoe stretching or cutting out the medial side of the forefoot toe box to accommodate the bunion deformity. When these modifications are unsuccessful, surgical options can be helpful. Surgical treatment goals include removing the exostosis, correcting the hallux valgus deformity, and straightening the toe, as well as relocating the sesamoid complex to be congruent with the underside of the first metatarsal head.

Many surgical options are available for bunion correction and are dependent on the degree of severity of the bunion deformity. The severity is typically measured radiographically with weight-bearing X-rays. The first and second IM angle, and the hallux valgus angle, the angle between the proximal phalanx and the first metatarsal, are measured. Treatment parameters for hallux valgus generally include whether the first MTP joint is congruent. An incongruent joint is one in which the proximal phalanx articular surface does not line up with the metatarsal head articular surface because of extreme hallux valgus. A normal hallux valgus angle is less than 20 degrees. Generally, when it approaches 30 degrees and is symptomatic, it requires correction. The IM angle is generally about 9 degrees. When the IM angle is less than 12 to 13 degrees, a distal corrective osteotomy may be done in the first metatarsal. With an IM angle greater than 13 degrees, one should consider a proximal first metatarsal osteotomy with distal soft tissue balancing. One final consideration is the sesamoids. Typically, they are subluxed laterally, and surgery should be tailored to make these bones congruent in their articulations with the base of the first metatarsal.

In this case, because of the IM angle, hallux valgus angle, and slight incongruence, a distal first metatarsal osteotomy was performed, and the distal aspect of the metatarsal was moved laterally to reduce the sesamoids. The medial capsule was imbricated and tightened, allowing for adequate stability of the first toe, as well as holding a corrected position.

Postoperative management included weight-bearing as tolerated in a postoperative shoe for 6 weeks, as well as a first–second toe spacer for 3 months. See the preoperative, immediate postoperative, and late followup pictures (Figs. 1, 2, 3, respectively) for details and radiographic results.

A

B

FIGURE 1. Preoperative radiographs with radiographic evidence of hallux valgus.

A

B

FIGURE 2. Immediate postoperative radiographs with corrective osteotomy and hardware in place.