- •Preface

- •1. Principles of Surgical Physiology

- •2. Essential Topics in General Surgery

- •3. Medical Risk Factors in Surgical Patients

- •4. Principles of Thoracic Surgery

- •5. Chest Wall, Lung, and Mediastinum

- •6. Heart

- •7. Peripheral Arterial Disease

- •8. Venous Disease, Pulmonary Embolism, and Lymphatic System

- •9. Common Life-threatening Disorders

- •10. Esophagus

- •11. Stomach and Duodenum

- •12. Small Intestine

- •13. Colon, Rectum, and Anus

- •14. Liver, Portal Hypertension, and Biliary Tract

- •15. Pancreas

- •16. Thyroid, Adrenal, Parathyroid, and Thymus Glands

- •18. Benign Lesions

- •19. Malignant Lesions of the Head and Neck

- •20. Parotid Gland

- •21. Trauma and Burns

- •22. Spleen

- •23. Breast

- •24. Organ Transplantation

- •25. Urologic Surgery

- •26. Plastic Surgery and Skin and Soft Tissue Surgery

- •27. Neurosurgery

- •28. Orthopedics

- •29. Pediatric Surgery

- •30. Laparoscopic Surgery

Chapter 28

Orthopedics

Vincent D. Pellegrini Jr.

John T. Ruth

Andrew H. Borom

I Orthopedic Patient Evaluation

A History

Pain. A thorough description of the patient's pain should be obtained, including the onset, location, duration, exacerbating factors, and character (e.g., aching, sharp, burning). What causes and alleviates the pain? Is it constant, present at rest, or only associated with activity?

Mechanism of injury. Many orthopedic complaints are related to an injury. A thorough description of the event that produced the patient's symptoms may often lead to the diagnosis. Specifically, the direction of force that acted upon a knee often gives insight into which ligaments might be injured (i.e., a patient who feels a “pop” during a twisting injury to the knee, which is followed by a large intra -articular knee effusion, often represents an acute anterior ligament rupture).

B Examination

Trauma patients. All trauma patients require a thorough palpation of all joints and bones. Specifically, the hands and feet should be inspected because fractures in these locations are often missed. The patient should always be log rolled to inspect and palpate the spine.

Regional or problem -oriented complaints. Patients with complaints about specific joints (e.g., the knee) deserve a thorough examination of that part, in addition to the joints both proximal and distal to it. The low back should also be examined because pain originating in the low back may produce symptoms more distally; this is called “referred pain.”

Patients with musculoskeletal tumors. These patients deserve a complete and thorough examination to rule out the possibility of metastases.

Neurovascular examination. All orthopedic examinations should include a thorough neurovascular examination, particularly for patients who have fractures or extensive lacerations of the extremities.

C Imaging studies

Plain radiographs should include views in at least two planes and always include the joints immediately above and below the presumed area of interest. Occasionally, oblique views are necessary. These views are most useful for fracture evaluation and should afford the examiner the ability to give a thorough description of the fracture to consultants.

Computed tomography (CT) scans are useful in orthopedics to evaluate complex articular fractures as well as fractures of the spine and pelvis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful for the evaluation of meniscal tears around the knee and rotator cuff tears at the shoulder, for diagnosing and defining the extent of osteomyelitis, for evaluating avascular necrosis of the femoral head, and for determining the intraosseous and extraosseous extent of primary bone tumors or metastases. Occult fractures, not apparent on plain x-rays, such as of the scaphoid or femoral neck, are most expediently diagnosed by MRI.

Bone scans are helpful for identifying occult fractures and for localizing sites of osteomyelitis. It is important to remember that although bone scans are very sensitive, they are often not very specific.

P.530

Ultrasound has become popular in the evaluation of the hip in infants and children. It is also used to define and diagnose rotator cuff tears.

II Trauma

A Overview

Orthopedic injuries with few exceptions are rarely acutely life threatening but can be limb threatening.

In the management of trauma patients, it is important to remember the guidelines of advanced trauma life support (ATLS) with strict adherence to the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation; see Chapter 21).

The extent of injury to the musculoskeletal system varies according to the patient's age, the direction of the energy causing the trauma, and the magnitude of the trauma.

The patient's age suggests the weak link in the musculoskeletal system.

In skeletally immature patients , the weak link is the growth plate at the ends of the long bones.

Young but skeletally mature patients (16–50 years of age) may be more likely to sustain ligamentous injuries because the relative strength of the mature bone exceeds the strength of the soft tissues supporting the joints.

In late middle-aged or elderly patients with significant osteopenia, injuries to the ligaments are uncommon. Instead, in this age group, fractures of the metaphyseal portions of long bones are prevalent (i.e., distal radius, hip). The metaphyseal area is at risk because the likelihood of osteopenia is much greater in this metabolically active area.

The direction of the trauma may determine which structures are injured. An example is the typical knee -dash injury that occurs in motor vehicle accidents. These injuries frequently cause fractures of the patella and femur as well as posterior hip fractures or dislocations.

The magnitude of the trauma is related to the energy imparted (E = ½ mv2 ), where m = mass and v = velocity.

High-energy injuries (e.g., in motor vehicle accidents) tend to cause shattered or “comminuted,” complex skeletal injuries, which may be open fractures.

Low-energy injuries, which frequently occur in sports, are more likely to cause simple, isolated injuries of ligaments, muscles, or bones.

Fracture

The radiographic appearance of a particular fracture may give insight into the type of trauma that produced it.

Description

Location may be the diaphysis (shaft), the metaphysis (juxta -articular), or through the joint surface (articular).

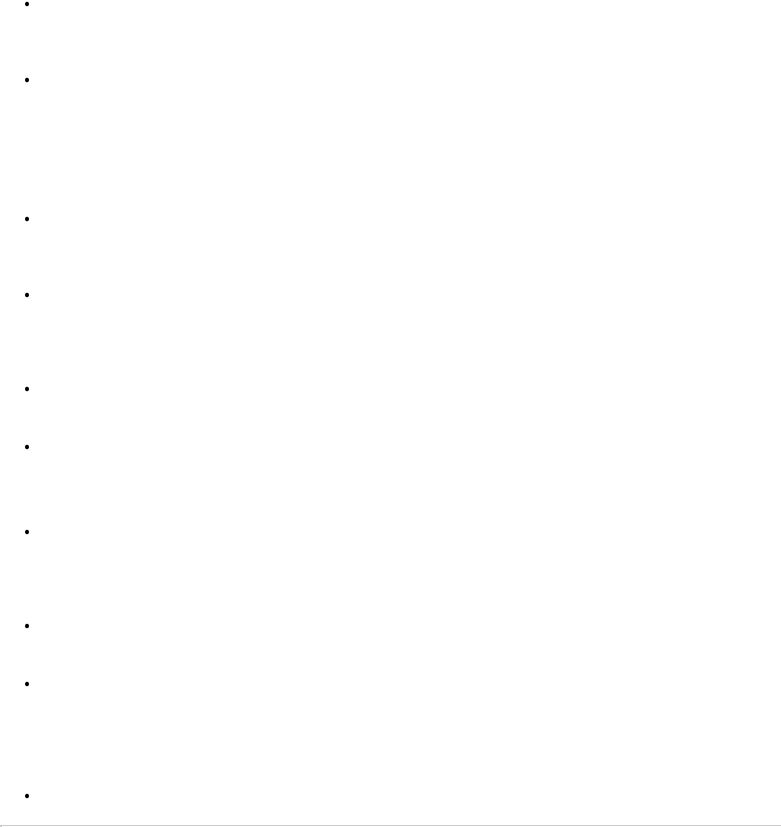

Orientation may be transverse, oblique, spiral, segmental, comminuted, or incomplete

(greenstick; in the growing skeleton) (Figs. 28 -1 and 28 -2).

Displacement may be expressed in terms of bone diameters (e.g., one bone diameter of displacement = 100% displacement) in shaft fractures and in millimeters of step-off in articular fractures (e.g., tibial plateau fractures).

Impaction frequently occurs in the proximal humerus and may indicate stability.

Angulation should use the apex of the fracture as a point of reference (i.e., apex dorsal).

Open or closed. Open, or compound (old terminology), indicates a soft tissue injury in the region of the fracture with exposure to the external environment.

All wounds in the proximity of fractures should be assumed to communicate with the fracture and therefore represent open injuries until proven otherwise.

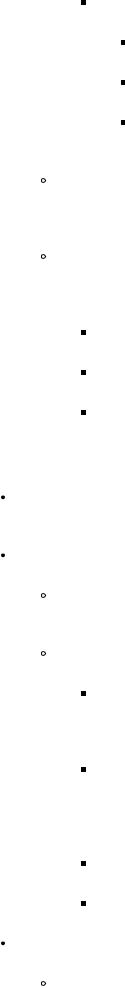

Open fractures are classified using the Gustilo classification (Table 28 -1).

Stress fracture implies a fracture resulting from abnormal stresses on normal bone (fatigue fracture) or normal stresses on abnormal or osteopenic bone (insufficiency fracture). Osteoporosis is a common cause of an insufficiency fracture.

Common sites in patients with normal bone include the tarsal bones (calcaneus), metatarsals, and tibial shaft.

Common sites in patients with osteopenic bone include the femoral neck, foot, pelvis, and vertebrae.

P.531

FIGURE 28-1 Fracture patterns. (Redrawn with permission from

Rang M. Children's Fractures, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1983:5.

)

FIGURE 28-2 Fracture patterns in children. (Redrawn with permission from Rang M. Children's Fractures, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1983:2.

)

P.532

TABLE 28-1 Classification of Open Fractures (Gustillo)

Grade 1: -Skin opening of 1 cm or less, quite clean; most likely from inside to outside; minimal muscle contusion; simple transverse or short oblique fractures

Grade 2: -Laceration more than 1 cm long, with extensive soft tissue damage, flaps, or avulsion; minimal to moderate crushing components; simple transverse or short oblique fractures with minimal comminution

Grade 3: -Extensive soft tissue damage including muscles, skin, and neurovascular structures; often a high-velocity injury with a severe crushing component

3A: -Extensive soft tissue laceration, adequate bone coverage; segmental fractures, gunshot injuries

3B: -Extensive soft tissue injury with periosteal stripping and bone exposure; usually associated with massive contamination

3C: -Vascular injury requiring repair

Reprinted with permission from Behrens F. Fractures with soft tissue injuries. In: Browrer BD, Jupiter JB, Levine AM, Trafton PG, eds. Skeletal Trauma Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1992:313.

Diagnosis

Plain radiographs are helpful if reactive healing has occurred.

Bone scans are quite sensitive but not specific.

MRI is very sensitive and has increased specificity if a linear signal change is present. The T2 image will most commonly demonstrate edema in the area of fracture.

Pathologic fractures sometimes overlap with insufficiency fractures, specifically those fractures that occur in osteopenic bone. More frequently, pathologic fractures refer to a fracture occurring in a bone weakened by a tumorous condition (i.e., a primary bone malignancy, myeloma, or metastatic disease).

Impending pathologic fractures refers to a lytic defect in bone, usually secondary to a metastasis, which is precariously large and weakens the bone to a worrisome degree requiring prophylactic stabilization to prevent a fracture.

This can occur with a lytic lesion greater than 2.5 cm in diameter.

Criteria include a lytic lesion that occupies 50% or more of the cortex on any radiographic view.

Also includes a lytic lesion that continues to produce pain despite radiation therapy.

B

Orthopedic urgencies require the initiation of definitive care within 6 hours of the injury.

Hip dislocations. A reduction delayed more than 12 hours may increase the likelihood of development of avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

Open fractures

Early debridement of contaminating material and devitalized tissue with stabilization has been shown to reduce the infection rate.

Management

Splinting is done in the field or emergency department with removal of gross contamination and placement of sterile dressings. (Once this is done, the dressings should remain intact until the patient reaches the operating room.)

Administration of a first-generation cephalosporin (vancomycin in patients who are allergic to penicillin) should be performed in the emergency department. Use of an aminoglycoside and penicillin should be considered for patients with large wounds or for those with soil or farm contamination.

Tetanus prophylaxis is administered.

Definitive irrigation and debridement are performed in the operating room with stabilization.

Penetrating injuries to joints

Because of the excellent bacterial growth media provided by joint fluid, all open-joint penetrations require formal irrigation and debridement either via arthrotomy or arthroscopy.

Common, unsuspected penetrations can occur in patients with knee -dash strikes from motor vehicle accidents.

P.533

TABLE 28-2 Common Sites and Etiologies of Compartment Syndrome

Site |

Etiology |

Calf |

Tibia fractures |

Forearm |

Supracondylar humerus fractures |

Foot |

Calcaneus fracture |

Thigh |

Crush |

Hand |

Crush |

Intra -articular injection of 40–60 mL of sterile saline at a point distant to the laceration aids in the diagnosis because the saline will leak out through the laceration, thus confirming the intra -articular penetration.

Compartment syndromes

Definition. A compartment syndrome involves an increase in the interstitial fluid pressure within an osseofascial compartment of sufficient magnitude to compromise the microcirculation, leading to necrosis of the muscle within the compartment and dysfunction of the nerves traversing the compartment.

Sites where compartment syndromes occur are listed in Table 28 -2.

Diagnosis

Pain out of proportion to what would normally be expected for the injury is a diagnostic key, as is pain with passive stretch of the myotendinous units within the compartment.

Pain and tenseness on palpation of the compartment is also a significant diagnostic feature.

The diagnosis is confirmed by intracompartmental pressure measurements. A measurement of 30 mm Hg or greater is distinctly abnormal. Inadequate tissue perfusion occurs when the intracompartmental pressure approaches 10–20 mm Hg of the diastolic blood pressure.

Treatment involves surgical fascial release of all involved compartments.

Necrotizing fasciitis caused by group A Streptococcus can present as a compartment syndrome but typically is accompanied by gas production in the soft tissues. This is a rapidly ascending infection that can lead to limb loss and death if early surgical debridement is not performed.

C

Orthopedic emergencies require the initiation of definitive care within 2 hours of the injury to prevent loss of life

or limb.

Fractures and dislocations associated with vascular injury constitute limb-threatening injuries.

Common sites include:

Distal femur

Proximal tibia

Supracondylar humerus (primarily in children)

Knee dislocations

Mechanisms that can cause fractures with vascular injuries include:

Gunshot wounds

High-energy accidents (e.g., motorcycle accidents)

The diagnosis is confirmed by:

Suspicion is based on proximity with clinical signs of vascular injury (Table 28 -3).

Ankle -brachial indices less than 0.9 are indicative of a vascular injury.

Duplex Doppler ultrasonography can be used to diagnose the injury.

Formal angiography can also help to confirm the diagnosis.

A one -shot intraoperative angiogram can prove useful if the extremity is clinically ischemic with absent pulses and time does not permit a formal angiogram.

P.534

TABLE 28-3 Physical Signs of a Major Arterial Injury

Absent or comparably weak pulses

Distal cyanosis

Expanding hematoma

Pulsatile bleeding

Comparably cold extremity

Distal paralysis and paresthesias

Bleeding not controlled with direct pressure

Treatment. Ideally, temporary placement of a vascular shunt followed by orthopedic stabilization of the fracture and subsequent formal vascular repair prevents disruption of formal repair by orthopedic manipulation during fracture reduction and fixation.

Outcome. The amputation rate approaches 100% if warm ischemia time exceeds 6 hours.

Some types of pelvic ring injuries can be life threatening because of exsanguinating hemorrhage.

Types

Injuries that disrupt the sacroiliac joint are secondary to anteroposterior compression, vertical shearing, or combined forces.

Occasionally, fractures that enter the greater sciatic notch can lacerate the superior gluteal artery.

Diagnosis is confirmed by the following:

An initial trauma anteroposterior radiograph can show a suspicious pattern.

Pelvic instability can occur with gentle pressure over the anterior iliac crests.

Management

Field and early emergency department management

Aggressive fluid resuscitation is undertaken.

A pneumatic antishock garment is applied with use of an abdominal binder.

An intra -abdominal source of hemorrhage is ruled out.

Emergent stabilization of a hemodynamically unstable patient includes:

External pelvic fixation to decrease:

Bleeding can start again from bony surfaces, and the patient can be in pain.

Pelvic volume is decreased and, therefore, space into which bleeding can occur is decreased, thus allowing tamponade.

A pelvic angiogram is taken with embolization of bleeding vessels if external fixation and aggressive fluid replacement fail to achieve hemodynamic stabilization.

Definitive stabilization

Closed or open reduction of the sacroiliac joint, sacrum, or posterior ilium is undertaken with internal fixation.

Open reduction and internal fixation of the anterior ring or continued external fixation is achieved.

D Fractures in children

Overview

Growth plate fractures. The growth plate is cartilaginous and, therefore, represents a weak point at

the ends of the bone.

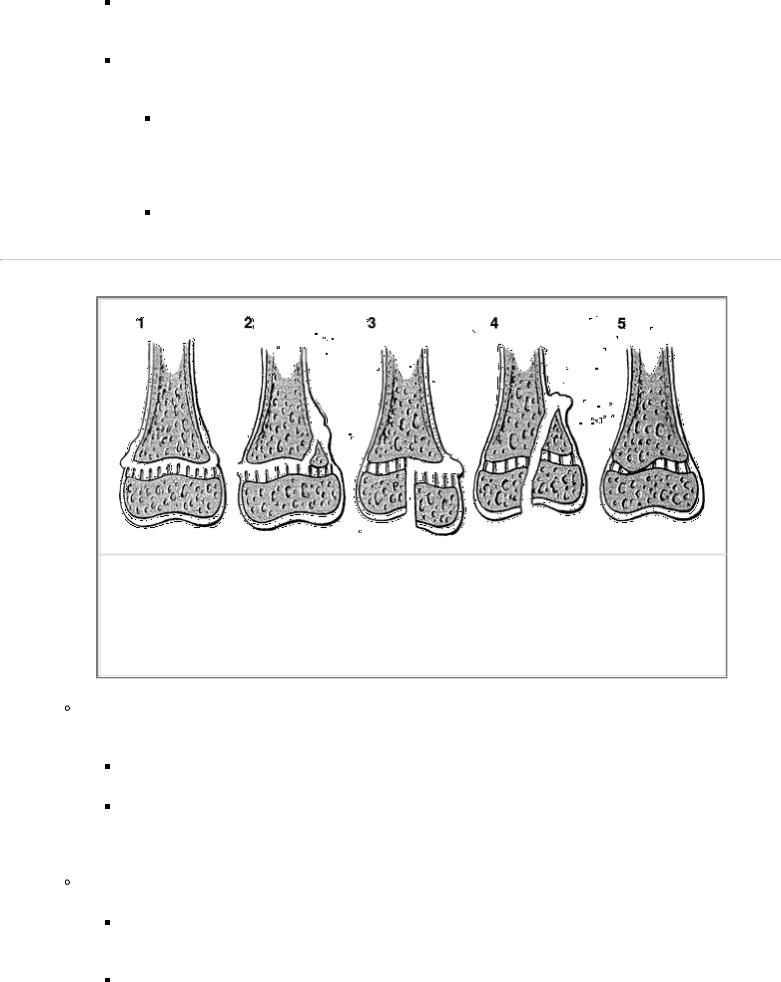

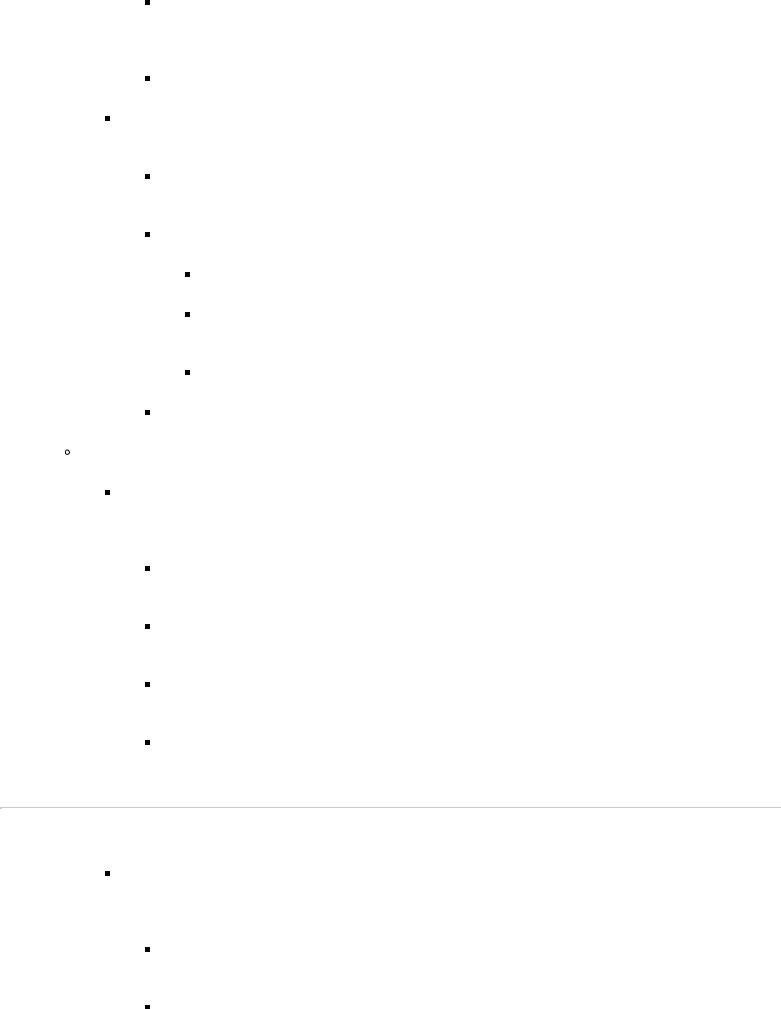

Classification. These fractures should be described using the Salter -Harris classification (Fig. 28 -3).

Types. All types of growth plate fractures may be associated with growth arrest, and the parents should be advised of this.

Types 3 and 4 frequently require open reduction and fixation because they are, by definition, intra -articular fractures. These injuries cross the growth cartilage with communication of bone on both sides of the growth plate and are therefore at greatest risk of causing growth arrest.

Types 1 and 2 frequently do well with closed reduction and cast immobilization; however, some types that are very unstable may require a pin or screw fixation. Growth arrest is an unlikely sequel to these injuries.

P.535

FIGURE 28-3 Salter-Harris classifications of epiphyseal fractures. (Redrawn with permission from

Salter RB, Harris WR. Injuries involving the epiphyseal plate. J Bone Joint Surg. 1963;45A:587.

)

Buckle (or torus) fractures (Fig. 28 -2) are incomplete fractures that occur in the metaphysis of bones adjacent to (but not involving) the growth plate.

A common site is the distal radius.

Treatment. Frequently, these fractures require only cast immobilization to prevent further angulation. Occasionally, a gentle closed reduction and a well-molded cast are required for more severely angulated fractures.

Greenstick fractures (Fig. 28 -2)

Site. Because of the flexibility and plasticity of a child's bones, some shaft fractures extend through only one side or one aspect of the cortex.

Treatment. Because of the potential for recurrent angulation despite an initial excellent closed

reduction, the remaining cortex of the fractured bone should be disrupted so that the alignment of the bone can be easily obtained and maintained.

Spiral fractures are unusual in children; the occurrence of a spiral fracture should always raise the question of child abuse.

A careful history obtained from the child's parents, caregiver, and siblings, as well as a complete physical examination, is important when differentiating fractures caused by accidents from those caused by child abuse.

A radiograph skeletal survey should be performed when child abuse is suspected. This usually includes anteroposterior projection of the trunk and extremities, plus anterior, posterior, and lateral views of the skull. Radiographs of the hands and feet can be requested if indicated.

Multiple fractures of varying age and stage of healing is diagnostic of child abuse. If any suspicion of abuse is present, social service/child protective consultation is mandatory.

Supracondylar fractures of the humerus

Displaced fractures require urgent attention.

The potential for compression or entrapment of the brachial artery can lead to limb ischemia and compartment syndrome.

The potential exists for entrapment of the radial and median nerves.

A careful neurovascular examination should be done before and after any attempts at reduction are made.

Treatment. For displaced fractures, a closed (occasionally open) reduction with pin stabilization and long-arm casting is frequently the treatment of choice. If swelling is thought to be too severe, then a brief period of lateral traction followed by pinning may be indicated.

Fractures of both forearm bones

In children, these fractures are usually managed with closed reduction and plaster immobilization. The casts must be carefully molded, and the patient must be closely observed acutely for possible compartment syndrome and to ensure that the interosseous space is preserved so that forearm rotation is maintained after healing.

P.536

In adolescents , an open reduction with internal fixation may be necessary if reduction is not satisfactory. Remodeling of the diaphysis is minimal after 10 years of age.

Distal radius fractures

The distal radial metaphysis is a frequent site for buckle fractures.

The distal radial epiphyseal plate is a frequent site for growth plate fractures. The growth plate fracture, if displaced, should have a closed reduction under anesthesia with cast immobilization.

Femur fractures

In children between the ages of 2 and 10 years, femur fractures can most often be managed with closed reduction and plaster spica cast immobilization.

It is desirable to have 1–1.5 cm of overlap to allow for the postfracture overgrowth that frequently occurs.

If overlap exceeds this amount, then a period of traction is indicated to restore length and allow early callus formation. This is followed by spica casting.

In children 11 years and older with an isolated femur fracture, treatment with an intramedullary rod, open plating, or external fixation is typically preferable to prolonged traction and spica casting. The physician should discuss with the parents the risks and potential benefits of all treatment options.

Regardless of the age, children who have multiple trauma or head injuries, in which prolonged traction would interfere with nursing care or could be potentially harmful because of the child flailing in bed, should be considered as candidates for operative fracture stabilization.

Plate or external fixation is preferable in children between the ages of 2 and 10 years.

Flexible intramedullary rods may be considered in children 11 years of age and older.

Supracondylar femur fractures and fractures of the proximal tibia can be easily confused with a ligamentous knee injury during the physical examination.

It is important to remember that skeletally immature individuals uncommonly have injuries to the ligaments. Rather, they frequently fracture the growth areas of the distal femur or proximal tibia, owing to the relative weakness of the junction of the growth plate with the adjacent ossifying cartilage.

When a child's knee is unstable on physical examination, one should assume a periarticular growth plate injury until proven otherwise. In the setting of normal plain x-rays, stress radiographs of the knee may be helpful to ascertain the exact cause and location of the motion.

Fractures of the tibia may be open because of the subcutaneous position of the bones.

These fractures can also be associated with a relatively high incidence of compartment syndromes.

Examination. All patients with tibia fractures should be examined for any skin disruption, and the neurovascular status of the leg should be evaluated and documented.

Treatment. These fractures in children are well managed with plaster immobilization. If larger open wounds are present, external fixation should be employed to allow access for wound care.

E Fractures in adults

Fractures of the spine, hip, the proximal humerus, and the distal radius at the wrist are all quite common in elderly persons with osteoporosis.

In general, distal radius fractures can be managed with closed reduction and cast immobilization. If unstable and maintenance of satisfactory reduction is unsuccessful, internal or external fixation of the fracture may be necessary.

Proximal humerus fractures may simply require collar and cuff immobilization. More severe fractures may require open reduction and internal fixation or prosthetic replacement. Early motion

after callus development is essential to decrease shoulder stiffness.

Because of the associated morbidity of bedrest and recumbency and the weight-bearing function of the hip, operative repair of the fracture or hemiarthroplasty is actually the conservative management and is associated with better long-term function and survival of the patient.

P.537

Simple osteopenic compression fractures can frequently be managed with bracing for 3–4 months. Metastatic disease should be ruled out as a cause.

Humeral shaft fractures may have an associated radial nerve palsy.

Generally, the palsy recovers spontaneously with immobilization. Careful attention must be paid to the hand to prevent stiffness and contractures until the radial nerve recovers.

If the palsy develops after closed reduction, then exploration is typically indicated to ensure that the nerve is not entrapped within the fracture site. Frequently, plate stabilization is performed at the same time.

The fracture, when isolated , may be treated with a sling and humeral fracture brace. Early range-of - motion exercises of the shoulder and elbow and isometric exercises for the biceps and triceps are indicated as well.

The fracture in conjunction with multiple trauma , other lower extremity fractures, or ipsilateral forearm and hand injuries frequently require intramedullary rod or plate fixation to allow use of a crutch or hand and upper extremity rehabilitation.

Fractures of both forearm bones

Because of the conjoined two bone system and precise functional requirements of the forearm, these fractures require open reduction and internal fixation for optimal functional results.

The consideration of compartment syndrome is important, especially in crushing injuries.

Distal radius fractures

If the distal radius fracture is extra-articular and results from a relatively low -energy injury, then it can frequently be treated by closed reduction and immobilization in a well-molded, long-arm cast.

If the fracture is intra -articular and results from a relatively high-energy injury (e.g., motor vehicle accident, fall from a height), then it frequently requires more aggressive treatment. Closed reduction with percutaneous pinning, external fixation, or open reduction and internal fixation may be used to obtain and maintain a satisfactory reduction.

If a distal radioulnar joint injury is suspected, then the forearm should be immobilized in full supination.

Scaphoid fractures

Wrist pain, especially in the anatomic snuff -box after a fall on an outstretched wrist, should arouse suspicion of this carpal bone injury. Healing is often delayed owing to a precarious blood supply to the bone, which is largely covered with articular cartilage.

Nondisplaced fractures are treated with thumb -spica casting, whereas displaced fractures require surgical open reduction and internal fixation.

Phalangeal fractures

Because of the precise, fine function of the extensor mechanism in the fingers and the problem of stiffness resulting from adherence of the tendons to the adjacent skeleton, early range-of -motion exercise of the fingers has a high priority.

Percutaneous pin or plate fixation to maintain the anatomical length of the skeleton, or closed treatment by splinting with “buddy” taping of stable fractures, are acceptable methods, assuming the goal of early motion can be obtained to avoid finger contracture and dysfunction.

Spinal fractures are associated with high-energy mechanisms of injury. Automobile accidents, motorcycle accidents, and falls from heights are frequent mechanisms in spinal fractures. Associated neurologic injury must always be considered and ruled out.

General initial treatment

All unconscious patients involved in motor vehicle or motorcycle accidents should be assumed to have a spinal injury until proved otherwise. Complete spinal radiographs are indicated to rule out these fractures.

All patients suspected of having a spinal injury should be immobilized on a long spine board with a cervical collar and head blocks.

A careful neurologic examination should be performed (including rectal examination, bulbocavernous reflex, and perirectal sensation) to distinguish between an

P.538

incomplete (i.e., some neurologic function present below the level of injury) and a complete (i.e., no function below the level of injury) neurologic injury to the spinal cord.

Cervical spine fractures are frequently associated with quadriplegia.

If one level of injury is found, there is an increased incidence of another level of injury in the cervical spine.

Cervical radiographs must include the C7 -T1 junction, because as a transition zone from a mobile (cervical) to a relatively immobile (thoracic) region, it is frequently a site of injury.

Thoracic spine fractures

When thoracic spine fractures are associated with paraplegia , a high-energy injury is usually implicated because of the relative stability provided in this region by the rib cage.

Simple compression fractures may occur in elderly osteopenic patients secondary to minimal trauma (e.g., coughing).

Metastatic disease can be present in patients with thoracic spine compression fractures.

Injuries between T1 and T10 with neurologic deficit frequently indicate a cord -level injury. Injuries from T11-T12 may include a mixed neurologic injury consisting of conus medullaris

(central) and spinal nerve roots (peripheral).

Lumbar spine fractures can present with a mixed neurologic injury from L1 -L2 with involvement of the conus medullaris (upper motor neuron) as well as the cauda equina (lower motor neuron or root lesion). Below L2, the injury typically involves only nerve roots.

Treatment

All patients with suspected neurologic injuries related to spinal cord injury should be started on a steroid protocol.

Methylprednisolone is given as a bolus dose of 30 mg/kg body weight, followed by an infusion of 5.4 mg/kg/hour.

In patients with acute spinal cord injury, this treatment protocol has been associated with improved neurologic recovery. Steroid therapy begun within the first 3 hours after an injury should continue for 23 hours. If steroids are started from 3–8 hours postinjury, they should be continued for 48 hours. If steroid therapy is not instituted in the first 8 hours, no neurologic benefit will occur.

Urgent decompression of neural elements in patients with incomplete or progressive neural deficits or injuries at the level of the cauda equina is the optimal approach.

Spinal stabilization with instrumentation to prevent the development or worsening of a neural deficit, and to facilitate early rehabilitation, should be performed.

Patients with complete quadriplegia or paraplegia should also be considered as candidates for spinal stabilization with instrumentation on a less urgent basis to allow early rehabilitation.

Pelvic fractures (see II C 2)

Femoral shaft fractures. Early stabilization of femoral fractures has been shown to decrease pulmonary complications and to shorten intensive care unit stays in the multiply injured patient.

The most universally accepted method of stabilization is placement of a statically interlocked intramedullary rod.

Traction is indicated on a short-term basis if the patient is considered to be too critically ill for surgery (e.g., severe coagulopathy, marked elevation of intracranial pressure). Formal stabilization should be performed as soon as the patient's condition is stable.

Intramedullary stabilization is the treatment of choice for isolated femoral shaft fractures. This is due to a relatively low complication rate and superior functional outcome when compared with traction followed by cast bracing.

Tibial fractures frequently may be open and can be associated with compartment syndromes. These two associated problems must be anticipated and managed appropriately.

Isolated fractures of the tibia are generally best managed with plaster immobilization and early weight bearing. Early return to function may be facilitated by intramedullary nailing of the tibial shaft fracture.

P.539

Patients with multiple injuries, open tibial fractures , and some fracture patterns known to be associated with the development of unacceptable shortening or malalignment should be considered candidates for intramedullary rods or external fixation. Plate fixation with an open tibial fracture has limited indication because of the further stripping of crucial blood supply typically necessary to place the plate.

Ankle fractures may involve the distal fibula, lateral malleolus, or medial malleolus.

Distal fibula or lateral malleolus. When significant displacement of the distal fibula with widening of the mortise is found on the initial radiographs, open reduction and internal fixation is most commonly indicated to provide stability to the ankle mortise.

Fractures of the medial malleolus in association with fractures of the distal fibula may indicate ankle instability resulting from a more violent mechanism of injury. Large, displaced fragments of the medial malleolus are an indication for open reduction and internal fixation to prevent the development of nonunion and to restore the articular surface.

Spiral fractures of the proximal fibula require a clinical and radiographic evaluation of the ankle joint. A Maisonneuve fracture implies disruption of the medial ankle (fracture or deltoid ligament tear), the intervening syndesmotic ligaments between the distal tibia and fibula, and proximal fibula fracture.

F Dislocations

Shoulder

Presentation. Dislocations of the glenohumeral joint are especially common in young adults. These dislocations frequently recur in patients under the age of 40. In first -time dislocations that occur after 40 years of age, a tear of the rotator cuff should be suspected.

Management. Shoulder dislocations are also associated with axillary nerve palsy. The neurologic examination should test for:

Sensation over the deltoid muscle

Active firing of the deltoid muscle

Hip

Presentation. Dislocations of the hip occur in high-velocity injuries, especially automobile accidents. They are associated with fractures of the ipsilateral femur and patella and with contralateral hip fractures or dislocations.

Management. Hip dislocations require prompt reduction to reduce the risk of avascular necrosis resulting from concomitant injury to the blood supply to the femoral head.

Knee

Presentation. A dislocation of the knee implies severe ligamentous injury around the knee.

Ligamentous knee injuries occur most commonly in sports-related activities.

Total ligamentous disruptions and dislocations are usually the result of violent injuries and may be associated with limb -threatening neurovascular injury.

Management. The most important consideration is the common occurrence of injuries to the popliteal artery and vein as well as to the peroneal nerve. The first step in management of a patient with a dislocated knee is to evaluate the neurovascular status of the lower extremity. Then, the ligaments and capsule around the knee are evaluated.

After a formal evaluation, a gentle closed reduction should be attempted.

All patients with knee dislocations deserve a formal angiographic evaluation of the femoral artery with runoff (one third will have vascular injury).

G Musculotendinous injuries

The musculotendinous unit is most commonly disrupted by overuse but may also be disrupted by forced lengthening of the muscle.

Tear of the rotator cuff

Presentation. Middle -aged and older patients with intermittent shoulder pain may have an episode of acute pain when the weakened tendon tears.

Management. Most tears are small and may be treated symptomatically. However, after acute symptoms resolve, if the shoulder demonstrates poor muscular function or continued pain despite nonoperative therapy (e.g., anti -inflammatory medication, physical therapy), operative repair should be considered.

P.540

Quadriceps disruptions

Presentation. Middle -aged and older patients, especially those with diabetes mellitus or renal disease, may acutely disrupt the quadriceps mechanism proximal to the patella.

Physical examination shows minimal swelling and tenderness. The patient has weakness in the leg after hearing a “pop” and may be able to raise the leg if the knee is passively placed in a straight position. However, the patient is unable to initiate extension against gravity with the knee at 90 degrees of flexion.

Surgical repair is indicated.

Patellar tendon disruptions

Presentation. These injuries often occur in young to middle -aged athletic patients. Often, the “weekend warrior” type of athlete sustains this type of injury.

A physical examination similar to that for a quadriceps disruption shows an inability to fully extend the knee against gravity.

Surgical repair is indicated.

Achilles tendon disruptions

Presentation. The patient is usually young to middle aged. Again, these injuries typically occur in the “weekend warrior” as opposed to professional athletes.

Typically, the patient feels a sharp pain or hears an audible “pop” in the posterior lower aspect of the leg. Frequently, the patient feels as if he or she has been kicked.

The patient is usually able to walk. The initial symptoms are minimal, although the patient does notice a significant decrease in plantar flexion strength.

Physical examination. A valuable test in the diagnosis of Achilles tendon ruptures is the Thompson test , which is performed by squeezing the calf and observing for plantar flexion of the foot while the patient lies prone on the examination table.

This test is usually performed in comparison with the uninjured lower extremity.

If plantar flexion of the foot is greatly decreased or absent with the squeezing maneuver of the calf, then this is a positive sign of an Achilles tendon rupture.

The treatment is surgical repair or cast immobilization with the ankle in plantar flexion.

Acute muscle ruptures. Any musculotendinous unit may be disrupted by forceful lengthening of the muscle. The disruption usually occurs at the musculotendinous junction but may be within the muscle belly. A typical example of a muscle belly tear is the medial head of the gastrocnemius complex in the calf. True muscular tears are best treated conservatively with immobilization or limited activity.

Ankle sprains are typically inversion injuries that involve the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) and less frequently the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL).

Treatment involves rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE).

Functional mobilization with a stirrup brace follows with weight bearing as tolerated.

III Infections

A Acute infections

Osteomyelitis

Clinical presentation. Hematogenous osteomyelitis is common in childhood.

In the metaphysis of children's bones, there is a unique capillary venous sinusoid underneath the growth plate. Minor trauma predisposes this sinusoid to sludging and allows organisms from minor bacteremic conditions to initiate an infection.

Infection can then erupt out of the medullary space and track beneath the periosteum and cause periosteal elevation. Loss of blood supply devitalizes the bone, and the resulting necrotic bone is called a sequestrum. The sequestrum becomes a nidus for recurrence of infection if it is not adequately debrided. The elevated periosteum lays down extensive new bone, which is termed an involucrum.

If the metaphysis is intra -articular, such as in the case of the hip or shoulder, then eruption of the infection out of the medullary space can enter into the synovial cavity and result in a septic arthritis.

P.541

Etiology

Pediatric

Staphylococcus aureus and gram -negative rods predominate as causative organisms in neonates.

Osteomyelitis in young children (i.e., 2–5 years of age) is frequently caused by

Haemophilus species as well as by Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.

S. aureus is the predominant causal organism in older children (i.e., 5 years or older) and adolescents.

A child with a history of minor trauma who does not improve as would normally be expected must be considered to have possibly developed osteomyelitis.

A child's refusal to bear weight on an extremity demands a workup for osteomyelitis or septic arthritis.

Adults whose immune system is suppressed (e.g., intravenous drug users) and patients with sickle cell disease are predisposed to osteomyelitis from hematogenous spread of unusual organisms.

Patients with immunosuppression and intravenous drug users are susceptible to gram -negative infections, particularly Pseudomonas aeruginosa

In patients with sickle cell anemia , a particularly high incidence of Salmonella osteomyelitis has been observed.

Gonococcal septic arthritis is the most common organism in adolescent, sexually active patients.

Diagnosis. A careful physical examination, complete blood count, sedimentation rate, and bone scan help to confirm the diagnosis. Needle aspiration of the affected bone or joint is the definitive diagnostic test.

Treatment includes appropriate intravenous antibiotics and surgical drainage. Initial antibiotic treatment should be selected to cover the most likely causes of organisms and should always include coverage for Staphylococcus.

Septic arthritis

Etiology

Spontaneous joint infections can occur in children or adults by the hematogenous spread of similar organisms that cause osteomyelitis.

Joint disease , as well as immunosuppression such as occurs in rheumatoid arthritis, can predispose the patient to these joint infections.

Physical examination demonstrates exquisite tenderness, effusion, and severe pain with minimal motion of the joint.

Diagnosis is confirmed by needle aspiration of the joint with synovial fluid analysis demonstrating a markedly elevated white blood cell count with predominance of polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

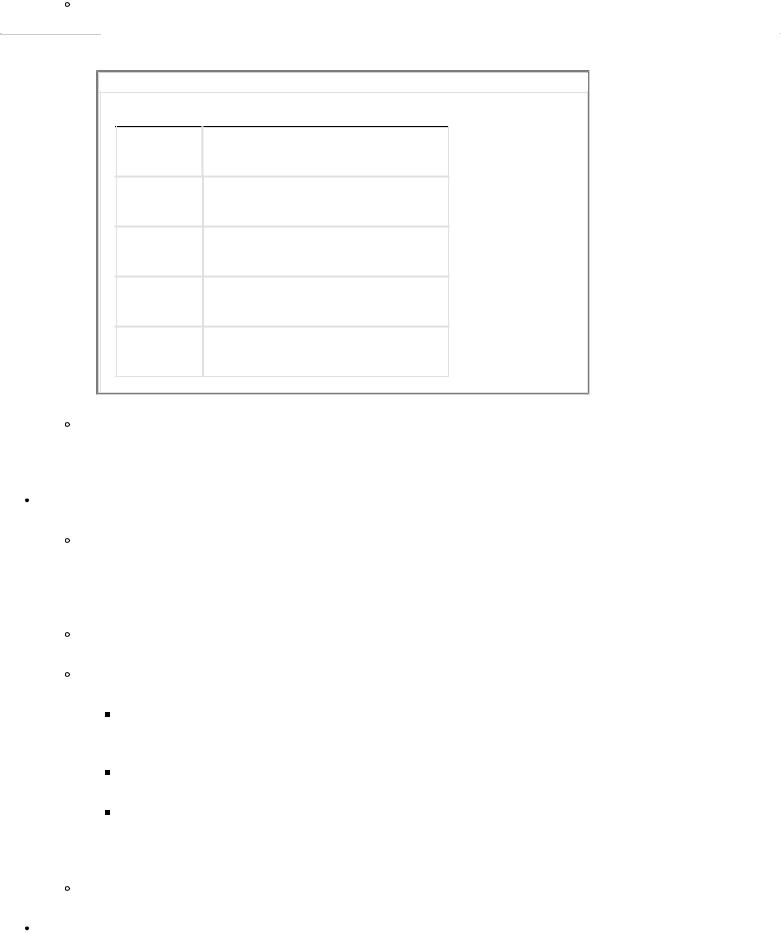

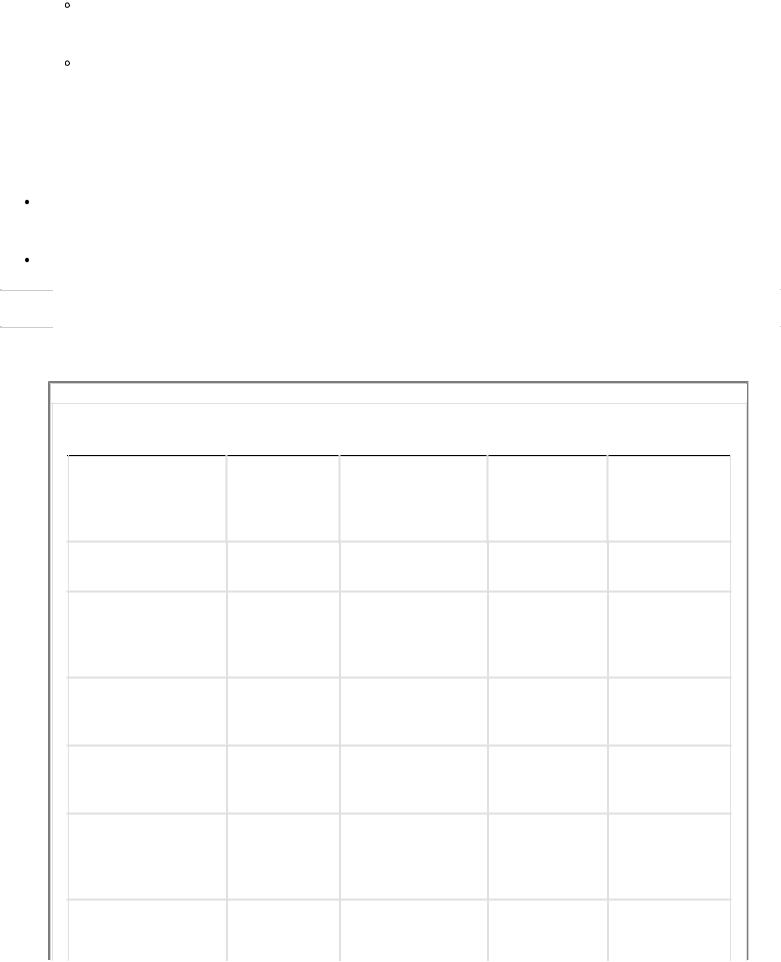

Synovial fluid white blood cells are greater than 50,000 with more than 90% polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The differential diagnosis includes rheumatoid arthritis and gout. A comparison of the synovial fluid analysis of septic arthritis with other types of arthritides is shown in Table 28 -4.

Treatment includes surgical decompression of the joint (either open or arthroscopic) and appropriate intravenous antibiotic therapy.

Antibiotic therapy should not be instituted before obtaining adequate specimens for a Gram stain, culture, and sensitivity. Penetrating wounds that reach a bone or joint can lead to infection. A common example of this is nail puncture wounds to the sole of the foot. Pseudomonas osteomyelitis has been reported frequently when the nail puncture wound has occurred through an athletic -type shoe.

B Chronic osteomyelitis

Etiology. Chronic osteomyelitis is uncommon; however, it is seen in patients who have had severe open fractures, in immunosuppressed patients, and in patients with pressure ulcerations secondary to paraplegia.

Clinical presentation. Osteomyelitis involving the bony cortex is a particularly difficult problem. Cortical bone has minimal vascularity and is even less well vascularized in the face of osteomyelitis.

P.542

P.543

Therefore, white blood cells, as well as antibiotics, have only limited access to the site of infection.

TABLE 28-4 Examination of the Synovial Fluid

|

|

Group I |

Group II |

|

|

Normal |

Noninflammatory |

Inflammatory |

Group III Septic |

Gross appearance |

Transparent, |

Transparent, |

Opaque or |

Opaque, |

|

clear |

yellow |

translucent, |

yellow to |

|

|

|

yellow |

green |

Viscosity |

High |

High |

Low |

Variable |

White cells/mm3 |

<200 |

<2,000 |

5,000–75,000 |

>50,000, |

|

|

|

|

often |

|

|

|

|

>100,000 |

Polymorphonuclear |

<25% |

<50% |

>50%, <90% |

>95% |

leukocytes |

|

|

|

|

Culture |

Negative |

Negative |

Negative |

Often |

|

|

|

|

positive |

Glucose (mg/dL) |

Almost |

Almost equal to |

>25, lower |

>50, lower |

|

equal to |

blood |

than blood |

than blood |

|

blood |

|

|

|

Associated |

— |

Degenerative |

Rheumatoid |

Bacterial |

conditions |

|

joint disease |

arthritis |

infections |

|

|

Traumaa |

Connective |

Compromised |

|

|

Neuropathic |

tissue |

immunity |

|

|

arthropathya |

diseases |

(disease or |

|

|

Hypertrophic |

(SLE, PSS, |

medication |

|

|

osteoarthropathyb |

DM/PM) |

related) |

|

|

Pigmented |

Ankylosing |

Other joint |

|

|

villonodular |

spondylitis |

disease |

|

|

synovitisa |

Other |

|

|

|

SLEb |

seronegative |

|

|

|

Acute rheumatic |

spodylo- |

|

|

|

feverb |

arthropathies |

|

|

|

Erythema |

(psoriatic |

|

|

|

nodosum |

arthritis, |

|

|

|

|

Reiter's |

|

|

|

|

syndrome, |

|

|

|

|

arthritis of |

|

|

|

|

chronic |

|

|

|

|

inflammatory |

|

|

|

|

bowel |

|

|

|

|

disease) |

|

|

|

|

Crystal- |

|

|

|

|

induced |

|

|

|

|

synovitis |

|

|

|

|

(gout or |

|

|

|

|

pseudogout) |

|

|

|

|

Acute |

|

|

|

|

rheumatic |

|

|

|

|

fever |

|

|

|

|

|

|

aMay be hemorrhagic

bGroup I or II

SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; PSS, progressive systemic sclerosis; DM/PM, dermatomyositis/polymyositis.

Reprinted with permission from Rodnan GP, Schumacher HR. Examination of synovial fluid. In: Primer on Rheumatic Diseases, 8th ed. Atlanta: Atlanta Arthritis Foundation; 1983:187.

Early treatment. Attempts to cure chronic osteomyelitis involve the removal of foreign material, including a thorough debridement of infected nonviable bone (sequestrum), open wound care, and a prolonged course of intravenous antibiotics.

Late treatment. After all devascularized bone and soft tissue have been removed, and once a stable wound base has been established, the overlying soft tissue and bone defect need to be addressed.

The bone defect can be packed with antibiotic -impregnated beads (frequently, tobramycin or commercially available gentamicin beads) followed by rotational or free vascularized tissue coverage. Later, the flap can be elevated; the beads can be removed; and massive cancellous autografting can be performed.

Use of a ring external fixator, such as the Ilizarov device , may be used to transport bone to fill defects. Occasionally, the wounds can be left open during transport, and they will close spontaneously once the defect is closed.

Use of vascularized bone grafts , such as the free vascularized fibula or fibular transposition graft, is

an option for large bone defects.

IV Tumors

A Primary bone tumors

Overview

Clinical presentation. The patient with a neoplastic bone lesion presents with pain, swelling, or occasionally, a pathologic fracture induced by minimal trauma. This is true for bony metastases as well as for benign and malignant primary tumors of bone.

Diagnosis. In addition to differentiating a primary tumor from a metastatic lesion of bone, some metabolic processes, such as hyperparathyroidism and infection, must be carefully considered.

Physical examination demonstrates the tumor mass, allowing the selection of appropriate radiographs.

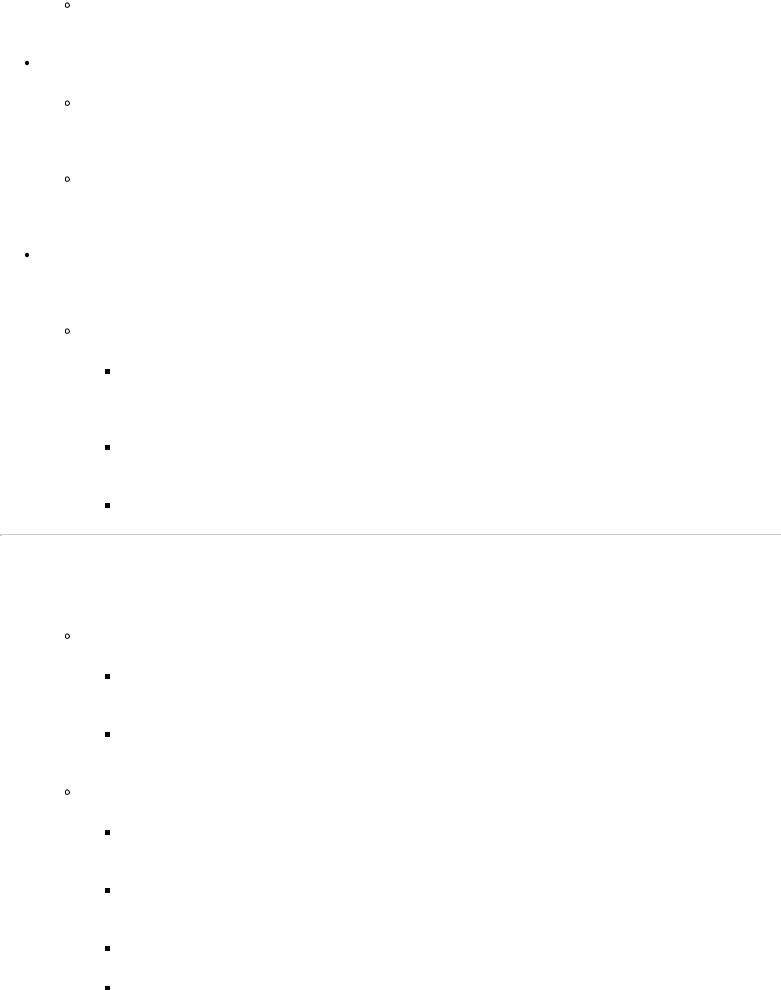

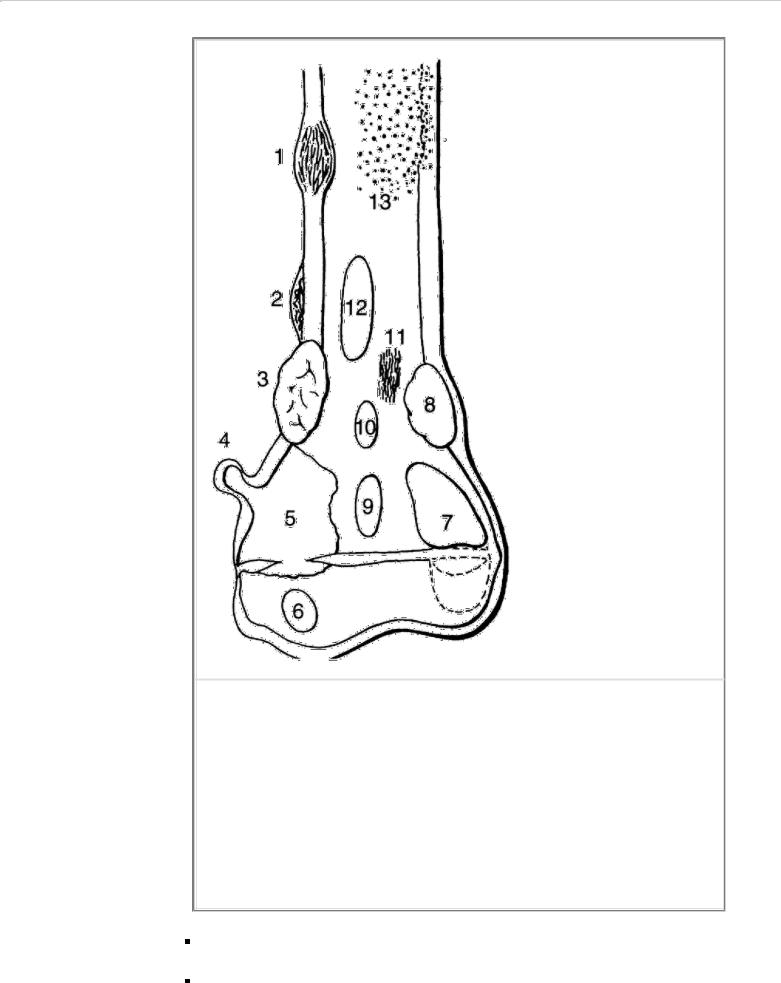

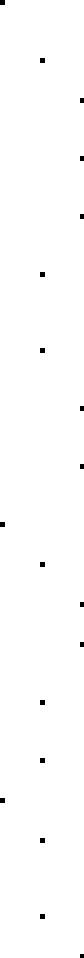

Plain radiographs alone often suggest the etiology and nature of the bone lesion based on its location, appearance, and the response of the surrounding normal bone (Fig. 28 -4).

Malignancy can be expected if the films show:

A large tumor

Aggressive destruction of bone

Ineffective reaction of the bone to the tumor

Extension of the tumor into soft tissue

Benign lesions can be expected if the films show:

A small, well-circumscribed lytic lesion

A thick, sclerotic rim of reactive adjacent bone

No extension into soft tissue

Workup. If there is any question whatsoever that the tumor is malignant, a careful workup must be performed before the biopsy. An incomplete workup or a poorly planned biopsy may prove fatal for the patient or result in loss of limb.

An appropriate workup includes a CT scan and MRI of the involved extremity to stage the tumor and delineate its extent and anatomic relationships. A technetium -99m

(99m Tc) scan is helpful in determining metastatic involvement of distant parts of the skeleton.

If malignancy is suspected, then a CT scan of the chest is important to rule out pulmonary metastases.

A biopsy should be performed only after staging has been completed. The biopsy should be carefully planned so that the biopsy incision can be excised with a definitive surgical resection. The biopsy is best planned and performed by the surgeon who will ultimately

carry out the definitive surgical procedure.

P.544

FIGURE 28-4 Schematic of the distal femur. Numbered sites represent tumor locations: (1) cortical fibrous dysplasia and adamantinoma; (2) osteoid osteoma; (3) chondromyxoid fibroma; (4) osteochondroma; (5) osteosarcoma; (6) chondroblastoma; (7) giant cell tumor; (8) nonossifying fibroma; (9) enchondroma or chondrosarcoma; (10) bone cyst or osteoblastoma; (11) fibrosarcoma or malignant fibrous histiocytoma; (12) fibrous dysplasia; and (13) Ewing's sarcoma or other small round tumors. (Redrawn with permission from

Moser RP, Madewell JE. An approach to primary bone tumors. Radiol Clin North Am. 1987;25[6]:1079–1080.

)

All biopsy incisions should be longitudinal on the limbs.

Biopsy incisions should be made through a muscle belly to avoid contaminating intermuscular planes.

Biopsy incisions should be directed away from neurovascular structures.

Incisions should be directed through structures that can be safely and successfully resected to leave a functional limb if radical excision is later indicated.

Treatment

Surgical treatment continues to be the mainstay of management for both benign and malignant tumors of the extremities. The surgical margin varies significantly with the aggressiveness of the lesion.

Benign tumors can be adequately treated by intralesional or intracapsular excision of the tumor with or without chemical cautery, electrocautery, or cryotherapy and with or without bone grafting of the defect.

Malignant tumors require at least a 2-cm margin.

Metastases. One or two isolated pulmonary metastases of sarcoma (especially osteosarcoma or chondrosarcoma) should be considered for surgical resection, because the literature shows that this occasionally results in a cure and certainly a prolonged life span in these patients.

Adjuvant therapy for malignant tumors

Radiation therapy

Some tumors (e.g., Ewing's tumors) are very sensitive to radiotherapy.

Some protocols include radiation therapy initially, but in general, radiation therapy is not an important part of the protocol.

Chemotherapy , like radiation therapy, may have an important role as adjunctive therapy in anticipation of limb -sparing procedures.

P.545

Ewing's tumors are well known to be very sensitive to various chemotherapeutic regimens.

Osteosarcoma appears to be sensitive to some chemotherapeutic agents, and work is under way to delineate the benefits, because chemotherapy may facilitate limb salvage.

Types of primary bone tumors

Tumors of bone cell origin

Benign osteoid osteoma is a painful lesion that commonly involves the femur or the tibia.

Epidemiology. The tumor occurs in adolescents, and more than 50% of the tumors present in patients aged 10–20 years.

Histology. The lesions are benign and are not prone to malignant degeneration.

Pathologic examination demonstrates a nidus of disorganized, dense, calcified osteoid tissue, which is histologically benign.

Treatment

Typically, aspirin offers excellent relief.

Surgical resection or stereotactical ablation is indicated for lesions that are persistently painful. A bone graft may be necessary.

Osteoblastoma is a benign, rare, painful lesion.

Epidemiology. This lesion occurs most often in the second decade of life and has a predilection for the posterior elements of the spine.

Histology. Osteoblastoma appears very similar to osteoid osteoma; one distinguishing feature is its size. An osteoblastoma is defined as a benign bone-forming lesion greater than 2 cm.

Treatment. Osteoblastomas are cured by surgical excision, if symptoms warrant. Bone grafting may be necessary.

Osteosarcoma

Epidemiology. More than 60% of patients with these tumors are 10–20 years of age.

Clinical presentation

At least 60% of osteosarcomas occur about the knee at either the distal femur or the proximal tibia.

Typically, the patient presents with pain and tumefaction.

Radiographically, the lesion is commonly lytic, but it may be a characteristically blastic lesion of the bone and produce a classic sunburst appearance. An MRI scan and a CT scan show that the lesion is ill-defined with soft tissue extension.

Histology. Histologically, the tumor may be predominantly fibrogenic, chondrogenic, or osteogenic; each of the three cell types predominates in approximately equal numbers of patients. The sine qua non of osteosarcoma is production of malignant osteoid by the tumor stroma.

Treatment

Surgical resection is the cornerstone of management; amputation or limb salvage surgery may be required.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (given before surgery) can narrow surgical margins and facilitate limb salvage. A high tumor kill rate observed in the resected specimen correlates favorably with long-term survival.

Adjuvant chemotherapy has a beneficial effect and has increased 5-year survival rates from 10%–20% with surgery alone only to almost 60% with combined

therapy.

Tumors originating in cartilage

Enchondromas are frequently incidental findings on radiographs, although some present as pathologic fractures.

Epidemiology. The tumor occurs in patients aged 10–50 and is commonly found in the hand.

Clinical presentation

It is typically an intraosseous lytic lesion marked by characteristic “popcorn” calcifications and surrounded by reactive sclerosis.

P.546

A tumor that appears radiographically to be an enchondroma must be suspected of being a sarcoma if the patient presents clinically with pain but no pathologic fracture.

Treatment. When an enchondroma causes a pathologic fracture, curettage and bone grafting are required, but such definitive treatment may be facilitated by first allowing the fracture to heal, especially in the small bones of the hand.

Osteochondromas are benign, easily palpable tumors of bone. They are quite common.

Clinical presentation

They grow during adolescence, as does any cartilage portion of bone. If pain or growth occurs after skeletal maturity, malignant degeneration must be suspected and excisional biopsy is warranted.

Osteochondromas may be symptomatic because of their prominence due to overlying tendon irritation or neurovascular compression.

Treatment. If symptoms warrant, osteochondromas can be excised, including the soft tissue covering and cartilage. Bone grafting is generally not necessary.

Chondroblastomas are less common cartilage tumors that almost always occur within the epiphysis of long bones.

Epidemiology. More than 70% of these tumors occur during the second decade of life. They are rare if the growth plates have closed.

Clinical presentation. They are benign lesions, but a few undergo malignant degeneration.

Treatment. They frequently require excision and bone grafting.

Chondromyxoid fibromas are relatively rare tumors.

Epidemiology. They usually occur in the first and second decades of life.

Clinical presentation. The tumor is a relatively large, well-defined lytic lesion with a sclerotic rim and is found in the metaphysis juxtaposed to the growth plate. It may present with pathologic fracture.

Treatment. Curettage and bone grafting may be required for treatment.

Chondrosarcoma is a primary malignant tumor that occurs in adulthood and sometimes develops in pre -existing benign cartilage lesions.

Epidemiology. It occurs with an essentially constant incidence in patients from 10–70 years of age.

Clinical presentation

Typically, the tumor presents with pain and tumefaction.

Radiographs may show a lytic lesion with or without stippled calcification. Cortical thickening and scalloping of the adjacent endosteal bone are frequently seen.

The tumor is locally recurrent.

Treatment is surgical, and the goal is to obtain a 2-cm margin of tumorfree tissue.

Other primary tumors

Giant cell tumors occur in the epiphyseal–metaphyseal region of long bones, especially about the knee in the femur and tibia and in the distal radius. The lesions are benign but are problematic because of their propensity to recur locally.

Epidemiology. Giant cell tumors occur in young adults and particularly in patients between the ages of 20 and 30. The patient is almost always skeletally mature.

Clinical presentation. The lesion usually extends to the subchondral plate of the joint. It is a lytic lesion and is fairly well circumscribed with some ballooning of the cortex.

Histology. The lesion is characterized histologically by the giant cells found in a benign stroma. The giant cell nuclei and the stroma nuclei are identical in appearance.

Treatment. Curettage is often accompanied by cryotherapy, phenol chemocautery, or electrocautery of the residual cavity. The lesion may be packed with methylmethacrylate bone cement, or bone grafting may be done. A recurrence usually requires wide resection of the involved bone.

P.547

Unicameral bone cysts are lytic expansile lesions of bone that occur in older children in the metaphyseal region that extends to the growth plate. The proximal end of the humerus is the most common site.

Clinical presentation. Typically, the patient presents with a pathologic fracture, and ultimately, the cyst may resolve in response to this trauma.

Treatment. Unicameral bone cysts may be managed with intralesional steroid injections

administered under radiographic control. Multiple injections may be required, which present a problem in growing children.

Ewing's sarcoma is a disease of childhood and adolescence. It occurs evenly among individuals younger than 20 years of age.

Clinical presentation

Typically, the patient presents with significant tumefaction and pain in the involved area.

The history, physical examination, and radiographic findings mimic those of osteomyelitis.

Radiologically, the lesion is seen to be a lytic bone lesion characteristically involving the diaphysis with some periosteal reaction.

Histology. Histologically, this is a tumor of small round cells, which may form pseudorosettes reminiscent of neuroblastoma. Chromosomal translocation t11:22 is associated with Ewing's sarcoma.

Treatment. The relative roles of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgical therapy are being evaluated.

These tumors are sensitive to both chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and together these modalities have a significant cure rate.

However, new information suggests that patients are at risk of forming osteosarcoma in the radiated bone during early adulthood.

Fibrosarcoma is a tumor that occurs in adulthood, between 20 and 70 years of age.

Clinical presentation

It is predominantly a lytic lesion that occurs in the femur and tibia about the knee.

It presents with pain and a radiographic appearance of a purely lytic lesion of bone.

Histology. Histologic examination shows sheets of spindle cells in a herringbone pattern and with various amounts of atypism.

Treatment involves wide surgical excision.

Multiple myeloma

Epidemiology. Whether this lesion is a primary tumor of bone or bone marrow is a matter of debate. Regardless of its classification, it is a common tumor that occurs in patients who are 30 years and older with a peak incidence at 50–60 years of age.

Clinical presentation

Multiple myeloma is characterized by overproduction of monoclonal

immunoglobulins or immunoglobulin subchains (Bence Jones protein).

The initial presentation is often a pathologic fracture, frequently of the spine or long bones.

The diagnosis should be suspected when lytic lesions are found in a patient with anemia, an elevated sedimentation rate, and elevated serum calcium levels.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can be made by serum or urine electrophoresis or immunophoresis in 95% of cases, but 5% of patients with myeloma are nonsecretors of M protein (immunoglobulins or Bence Jones protein).

Biopsy of the bone marrow to identify secreting and nonsecreting tumors shows plasma cells replacing the marrow. The percentage of bone marrow replacement offers some prognostic information.

Plain radiography reveals punched -out lytic lesions, with little adjacent reactive bone, that occur frequently in the spine, pelvis, proximal femur, and skull.

Bone scans are typically “cold” in the absence of pathologic fracture.

P.548

Treatment is by a combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy with palliative surgical fixation of pathologic fractures to improve the patient's quality of life.

B Metastatic disease

Tumors metastatic to the skeleton are more common than primary musculoskeletal tumors. Primary tumors that metastasize to bone include carcinomas of the breast, lung, prostate, thyroid, and kidney, or indeed, almost any type of tumor.

Diagnosis

Most bony metastatic disease presents with pain in the involved bone. Metastatic bone disease may be the initial presentation of a malignancy.

Radiographs show most bone lesions to be lytic. With some breast tumors and most prostatic tumors, the bone lesion has a blastic appearance.

Bone scans are helpful when a single symptomatic lytic lesion is found on initial radiographs.

If the bone scan shows multiple lesions, the likelihood of metastatic disease is high.

Bone scanning may also demonstrate a lesion that is likely to cause a fracture.

Skeletal metastases of unknown origin are best worked up with a history and physical examination; whole -body bone scan; plain radiographs of the chest and the involved bone; and a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

Treatment

The treatment for most metastatic lesions in bone is radiation therapy. If the pain does not respond

to irradiation, a pathologic fracture has probably occurred (or is about to occur) and should be surgically fixed. Pathologic fractures generally should be fixed internally, using a combination of metal implants plus methylmethacrylate bone cement to manage bone loss.

Impending pathologic fractures (see II A 3 e)

V Arthritis

A Classification

Degenerative joint disease

Primary osteoarthritis is typically seen with Heberden's nodes and asymmetric hip, knee, and spine involvement. The site of primary pathology is the articular cartilage.

Post -traumatic arthritis of an isolated joint can occur following trauma to that joint.

Rheumatoid arthritis and its variants include the autoimmune group of inflammatory diseases in which the hyaline articular cartilage is secondarily attacked by a local invasive pannus that primarily involves the synovium.

Crystal deposition diseases include gout and calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease. These diseases usually present as an isolated hot, inflamed joint.

Infectious arthritis (see III A 2) also presents as an isolated hot, inflamed joint.

This is the one form of arthritis that requires immediate emergency care.

The diagnosis can be made by aspirating the joint fluid and examining it microscopically for cells, organisms, and crystals as well as by cell count and culture.

B Nonoperative management

Pharmacologic management is maximized by consultation with a rheumatologist.

Nonsteroidal anti -inflammatory drugs (NSAID)

NSAIDs are especially important in rheumatoid arthritis, which requires a long-term maintenance regimen.

The crystalline and degenerative joint diseases require NSAIDs during acute flare -ups, but the natural history of these diseases is not altered by long-term management with these drugs.

Corticosteroids

These can be used in rheumatoid arthritis when NSAIDs fail to quiet the inflammation.

They can be used systemically if multiple joint involvement or generalized disease is the problem.

P.549

They can be used locally by instillation into a single joint in patients with degenerative or post-traumatic rheumatoid arthritis.

Immunosuppressants or cytotoxic agents such as methotrexate are being used more frequently to avoid detrimental side effects of chronic steroid use and as a disease -modifying agent.

Gold and remittive agents are indicated when the patient has not been successful with NSAIDs but are often poorly tolerated.

Anti -TNF (tumor necrosis factor) alpha agents are a recent addition to the armamentarium in treating rheumatoid disease and have shown great promise as disease -modifying agents.

Exercise and splinting have an important place in the treatment of all forms of arthritis after the acute joint inflammation has been controlled. The exercise is designed to maintain a full range of joint motion as well as to maintain muscle strength by exercising the joint through a limited, painless arc of motion. Splinting in a functional position prevents establishment of contractures.

C Operative management

Types of surgical procedures

Osteotomy

If the bone is cut and the joint is realigned, this may alter the mechanics enough to give significant, although incomplete, relief from pain.

In order for the osteotomy procedure to be successful, the disease process must not have completely destroyed the joint but must leave some remaining articular surface.

Osteotomy is designed to transfer weight bearing onto this relatively normal articular surface in the setting of noninflammatory arthritis.

Osteotomy about the hip and knee can be performed as a temporizing measure in patients too young to consider arthroplasty but who wish to preserve motion.

Arthrodesis

In this procedure, the joint surfaces are excised and the extremity is immobilized so that the joint heals in a fixed position.

Arthrodesis is indicated for the relief of pain, especially in young individuals.

The results of arthrodesis are very durable and long lasting.

Any patient who is young or has a high functional demand should be considered for arthrodesis rather than for arthroplasty.

Arthrodesis is commonly used in the small joints of the wrist, hand, foot, and ankle in all age groups.

Arthroplasty , or total joint replacement, relieves pain, preserves motion and is the most common surgical treatment for arthritis.

It can be used for joints destroyed by any of the arthritides; however, postinfectious arthritis is a relative contraindication to arthroplasty because of the increased risk of infection around the implant.

Arthroplasty is indicated for the relief of pain predominantly in patients who are usually older and less active.

At the present state of the art, the typical “life expectancy” for a hip or knee arthroplasty implant is about 15 years, depending on the functional requirements and weight of the patient. Failure is at a rate of roughly 1% per year.

Major joints such as the hip, knee, shoulder, and elbow are common sites for arthroplasty.

VI Pediatric Orthopedics

A

Developmental dislocation of the hip (DDH) is most common in female neonates, especially if the child is firstborn and was in the breech presentation. The condition is bilateral in 10% of patients.

Diagnosis can be made within the first 2 weeks after birth, once relaxin is gone from the child's circulation.

P.550

Physical examination

The examiner can feel a click on reduction of the dislocated hip (Ortolani's sign).

The examiner is able to dislocate the hip with the thigh flexed to 90 degrees (Barlow's test).

Other physical findings (especially if the dislocation is unilateral) include asymmetry of the gluteal fold and asymmetric leg lengths, which are demonstrated by the height of the thigh when the hips are flexed to 90 degrees.

Radiographs confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment. A hip that can still be dislocated after 2 weeks of age should be treated.

The initial management is with a Pavlik harness.

Double and triple diapering probably has no significant effect on the dislocation.

Persistent dislocation of the hip after the commencement of ambulation typically requires surgical treatment.

B Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

Etiology

Idiopathic osteonecrosis of the proximal femoral epiphysis can cause this disease.

This disease typically occurs in children 4–10 years old who are small for their age.

Males are affected more than females (5:1).

Clotting abnormalities and endocrinopathy (hypothyroidism) have been associated with Perthes disease.

Diagnosis

Patients often complain of knee pain, which is “referred” from the hip. In a child, this complaint should prompt an evaluation of the hip.

Hip irritation and limitation of internal rotation and abduction are common.

Radiographs of the hip demonstrate variable degrees of collapse of the femoral epiphysis.

Treatment

Restoration of range of motion and containment of the femoral head within the acetabulum are the cornerstones of treatment.

Traction followed by splinting in the abducted and internally rotated position may be tried.

Surgery may be necessary to redirect the femoral head into the acetabulum to allow it to reossify in a shape that matches the acetabulum and is as spherical as possible.

The single factor that is most predictive of a good outcome is the age at presentation (infants < 6 years old tend to do well regardless of treatment).

C Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE)

Etiology

SCFE was thought initially to be idiopathic; however, new evidence may point to a subtle endocrinopathy.

Hypothyroidism should be suspected in children who develop SCFE before the age of 10–12 years.

There is a high incidence in children with renal failure and also in African -American males and obese children.

Diagnosis

A patient who is 10–13 years of age with hip or knee pain should be suspected of having SCFE.

Anteroposterior and frog lateral radiographs of the hip should be obtained in all patients who are suspected of having SCFE.

SCFE is bilateral in 20%–40% of patients without endocrinopathy and in 50% with endocrinopathy.

Treatment. Stabilization in situ with a single screw placed into the center of the femoral capital epiphysis is the preferred treatment.

DScoliosis

Etiology

Etiology

The most common form of scoliosis in the United States is the idiopathic scoliosis that occurs most commonly in adolescent females, beginning approximately at 11 or 12 years of age and progressing until growth is completed.

P.551

Scoliosis can also be the result of neuromuscular paralysis, painful lesions, radiation, thoracic surgery, and congenital anomalies.

Clinical presentation

Idiopathic scoliosis occurs most commonly as a right thoracic curve, but thoracolumbar, lumbar, and double major curves can occur.

Thoracic curves are most noticeable because of the associated chest rotation and deformity, which create a rib hump.

If the scoliosis is severe, exceeding about 90 degrees, significant cardiopulmonary complications can occur as a result of compromise of the chest cavity.

Treatment

Braces. The Milwaukee and Boston braces are traditionally the initial form of treatment for scoliosis. They may eliminate the need for surgery in many patients.

The brace is not expected to correct a curve that is already established when the diagnosis is made but is meant to prevent progression of the scoliosis.

A brace is used if the curve measures about 20 degrees in a patient with significant growth still remaining.

The patient is placed in a brace if the scoliosis, even with a smaller angle, is clearly progressing during a period of observation.

Surgery

Various surgical techniques are available, but the one that is most commonly performed is bone graft fusion of the spine over the area of the curve, facilitated by rod fixation using a segmental system with screws into the pedicles of the vertebrae.

Significant (although never complete) correction is obtained, and the long-term results are maintained by fusion of the spine in the corrected position.

E

Foot deformities constitute a large part of pediatric orthopedic practice.

Etiology

Idiopathic foot deformities are quite common and include metatarsus adductus, talipes equinovalgus (clubfoot) , and planovalgus.

A careful neurologic evaluation must be done to make sure that the foot deformity is not due to a neuromuscular disorder. Poliomyelitis, cerebral palsy, myelomeningocele, diastematomyelia, and Charcot -Marie -Tooth muscular atrophy can all present with foot deformities.

Developmental dislocation of the hips must be ruled out whenever a child presents with a foot deformity.

Flatfoot seldom presents a significant problem and does not need treatment unless it causes symptoms or unless the neurologic examination is abnormal.

Clubfoot requires early treatment.

Repeated manipulation and casting will correct the deformity in many cases.

However, if the foot is relatively resistant to manipulation and casting, surgery may be indicated.

In recent years, surgical soft tissue releases before 1 year of age have shown a better prognosis than manipulation and casting.

Recurrence of the clubfoot despite correction remains a problem until the cartilaginous anlage of the child's foot has become the fixed osseous bone of the adolescent.

Neuromuscular foot disorders

Treatment of the “neuromuscular foot” includes initial correction to a plantigrade neutral foot, either by manipulation of the very immature foot or by osteotomy and fusion of the more mature adolescent foot.

Once the foot alignment is corrected, muscle transfers are carried out to prevent recurrent deformity. Tendons are transferred to replace the function of a paralyzed foot or to weaken the function of a spastic foot.