- •Preface

- •1. Principles of Surgical Physiology

- •2. Essential Topics in General Surgery

- •3. Medical Risk Factors in Surgical Patients

- •4. Principles of Thoracic Surgery

- •5. Chest Wall, Lung, and Mediastinum

- •6. Heart

- •7. Peripheral Arterial Disease

- •8. Venous Disease, Pulmonary Embolism, and Lymphatic System

- •9. Common Life-threatening Disorders

- •10. Esophagus

- •11. Stomach and Duodenum

- •12. Small Intestine

- •13. Colon, Rectum, and Anus

- •14. Liver, Portal Hypertension, and Biliary Tract

- •15. Pancreas

- •16. Thyroid, Adrenal, Parathyroid, and Thymus Glands

- •18. Benign Lesions

- •19. Malignant Lesions of the Head and Neck

- •20. Parotid Gland

- •21. Trauma and Burns

- •22. Spleen

- •23. Breast

- •24. Organ Transplantation

- •25. Urologic Surgery

- •26. Plastic Surgery and Skin and Soft Tissue Surgery

- •27. Neurosurgery

- •28. Orthopedics

- •29. Pediatric Surgery

- •30. Laparoscopic Surgery

Chapter 11

Stomach and Duodenum

Ernest L. Rosato

Francis E. Rosato Jr.

I Stomach

A

The functions of the stomach are storage; emulsification; initial digestion by acidification and salivary amylase; and transmission of food to the duodenum.

BEmbryology

1.The stomach and duodenum are derived from a dilatation of the foregut during the fifth week of development.

2.The rate of growth of the left wall outpaces the right, thus forming the greater and lesser curvatures. Rotation of the stomach causes the left vagus to lie in the anterior position and the right vagus to lie in the posterior position.

3.The ventral and dorsal mesentaries of the foregut become the lesser and greater omentums, respectively, in adult life.

4.The stomach usually is situated between vertebral bodies T10 and L3 and is fixed at both the gastroesophageal junction and the proximal duodenum.

CAnatomy

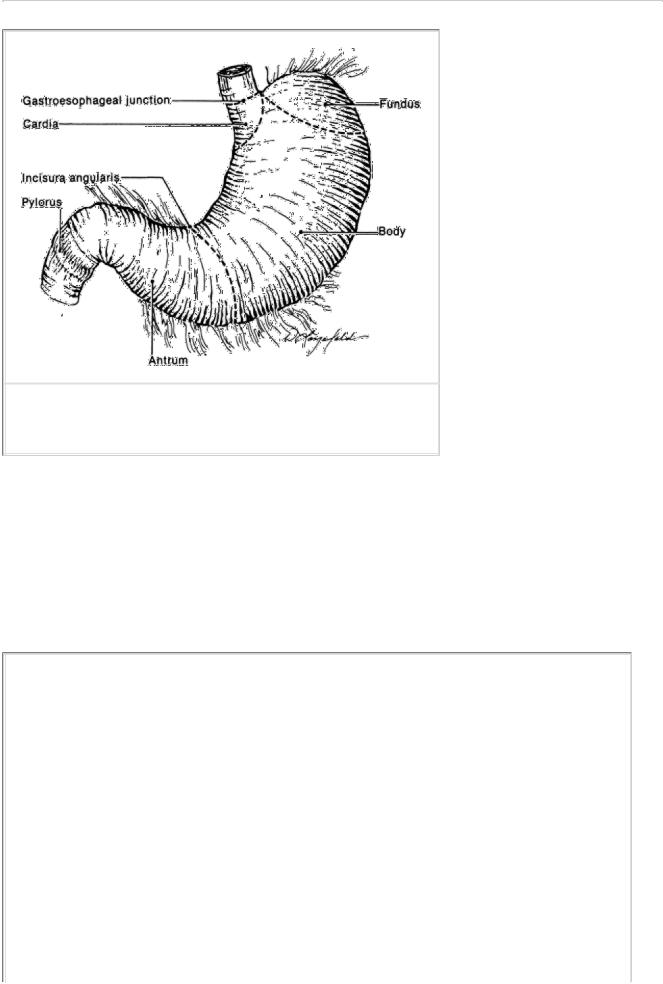

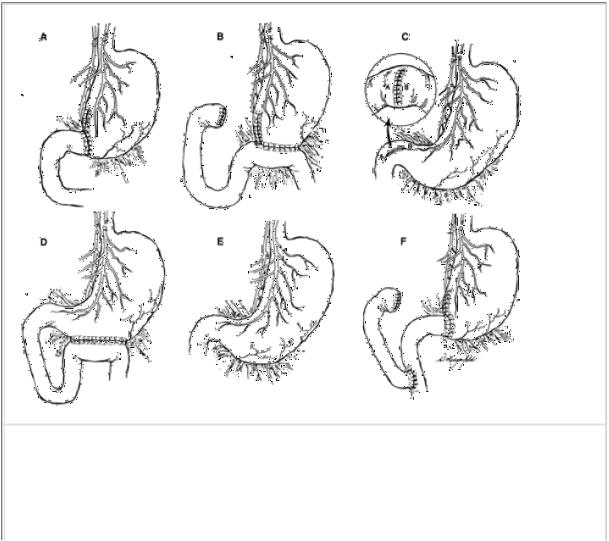

(Fig. 11-1). The stomach has four parts and two sphincteric mechanisms.

1.Portions of the stomach

a.The cardia is the most proximal portion of the stomach, where it attaches to the esophagus. Immediately rostral to this area is the gastroesophageal (GE) junction. This transition zone is found 2–3 cm below the diaphragmatic esophageal hiatus and contains the lower esophageal sphincter mechanism.

b.The fundus is the most superior extension of the stomach, bounded by the diaphragm superiorly and the spleen laterally. The angle created by the fundus and the left lateral border of the esophagus is referred to as the angle of His.

c.The body, also referred to as the corpus, is the largest portion of the stomach. It consists of the lesser and greater curves. The incisura angularis creates an abrupt angle along the lesser curvature and marks the beginning of the antrum.

d.The antrum is the distal 25% of the stomach. It begins at the incisura angularis and ends at the pylorus.

2.Sphincters of the stomach

a.The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) is a physiologic sphincter. It is a high-pressure zone of muscular activity in the distal esophagus.

1.Relaxation with swallowing allows entry of food into the stomach.

2.Contraction prevents reflux of food from the stomach into the esophagus.

b.The pylorus is an anatomic sphincter muscle. It controls the flow of food from the stomach into the duodenum.

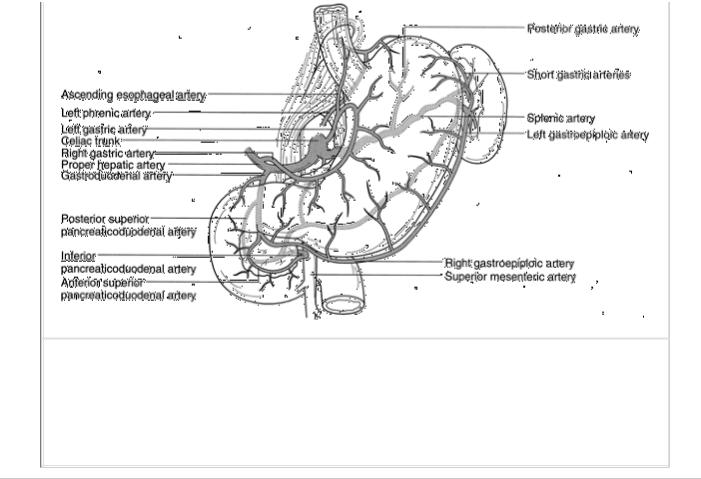

3.Arterial supply. The stomach has an extremely rich blood supply (Fig. 11-2), provided by the following vessels:

a.The left gastric artery (branch of celiac axis) supplies the lesser curvature (proximal).

b.The right gastric artery (branch of common hepatic artery) supplies the lesser curvature (distal).

c.The left gastroepiploic artery (branch of the splenic artery) supplies the greater curvature (proximal).

P.200

FIGURE 11-1 Anatomy of the stomach.

d.The right gastroepiploic artery (branch of gastroduodenal artery) supplies the greater curvature (distal).

e.The vasa brevia (short gastric arteries arising from the splenic artery) supply the fundus and body.

4.Venous drainage of the stomach in general parallels the arterial supply but has some portal drainage.

a.The right gastric and left gastric (coronary) veins drain into the portal vein, while the right gastroepiploic vein drains into the superior mesenteric vein, and the left gastroepiploic vein drains into the splenic vein.

b.The left gastric vein (coronary vein) has multiple anastomoses with the lower esophageal venous plexus. These drain systemically into the azygous vein.

FIGURE 11-2 Arterial supply and venous drainage of the stomach. (From

McKenney MG, Mangonon PC, and Moylan JP, eds. Understanding Surgical

Disease. Philadelphia: Lippincott–Raven Publishers; 1998:118. Used by permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.)

P.201

5.The nervous innervation of the stomach is via parasympathetic and sympathetic fibers.

a.The vagus (parasympathetic) nerves stimulate parietal cell secretion, gastrin release, and gastric motility. Acetylcholine is the primary neurotransmitter used by the efferent fibers.

1.The left vagus nerve lies anterior to and left of the esophagus. It supplies branches to the anterior portion of the stomach and a hepatic branch to the liver, gallbladder, and biliary tree.

2.The right vagus nerve lies posterior to and right of the esophagus. It supplies branches to the posterior stomach and a celiac branch to the pancreas, small bowel, and right colon. Its first branch is called the criminal nerve of Grassi and is recognized as a cause of recurrent ulcer when left undivided.

3.The vagus nerves become the anterior and posterior nerves of Laterjet, which terminate at the pylorus as the “crow's foot.”

b.Sympathetic innervation is via the greater splanchnic nerves derived from spinal segments T5 through T10. These fibers terminate in the celiac ganglion, and postganglionic fibers follow the gastric arteries to the stomach. The afferent fibers are the pathway for perception of visceral pain.

6.Lymphatic drainage of the stomach is extensive but can be divided into four general zones. It is important to note that cancer anywhere in the stomach can spread equally to any zone.

a.Superior gastric nodes drain the upper lesser curve and cardia region.

b.Pancreaticolienal nodes drain the upper great curve and splenic nodes.

c.Suprapyloric nodes drain the antral segment of the stomach.

d.Inferior gastric/subpyloric nodes drain along the right gastroepiploic vessels.

7.The four layers of the stomach wall are the serosa, muscularis, muscularis mucosa, and mucosa.

a.The layers of muscle fibers found in the muscularis are the inner oblique, middle circular, and outer longitudinal.

b.The mucosal morphology is composed of distinctly different types of glands unique to the cardia, fundus/body,

and pylorus/antrum.

1.Cardiac glands occupy a narrow zone up to 4 cm long adjacent to the LES. These glands function mainly in producing mucus.

2.The fundus and body contain gastric glands with specialized cell types.

a.Mucous cells provide an alkaline coating for the epithelium. This coating facilitates food passage and provides some mucosal protection.

b.Chief cells are found deep in the fundic glands. They secrete pepsinogen, which is the precursor to pepsin. Pepsin is active in protein digestion. Chief cells are stimulated by cholinergic impulses, gastrin, and secretin.

c.Oxyntic or parietal cells are found exclusively in the fundus and body of the stomach. They are stimulated by gastrin to produce hydrochloric acid as well as intrinsic factor.

3.The pyloroantral mucosa is found in the antrum of the stomach.

a.Parietal and chief cells are absent here.

b.G cells, which secrete gastrin, are found in this area. They are part of the amine precursor uptake and decarboxylase system of endocrine cells. Gastrin stimulates hydrochloric acid and pepsinogen secretion and gastric motility.

IIDuodenum

A Anatomy

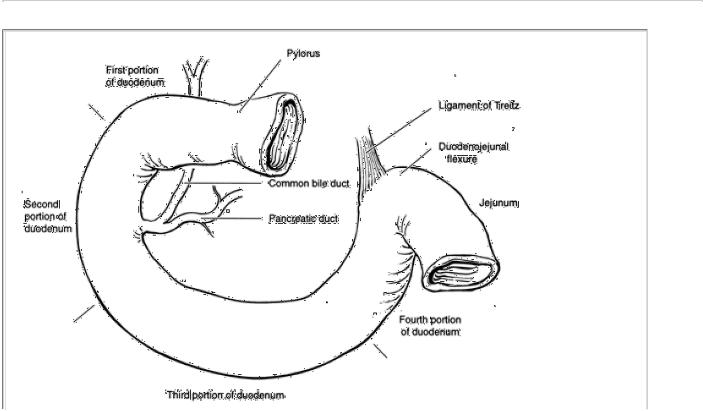

(Fig. 11-3). The duodenum is divided into four sections. The first portion (duodenal cap) is 5 cm long, the second (descending) portion is 7 cm long, the third (transverse) portion is 12 cm long, and the fourth portion is 2.5 cm long.

BVasculature

1.Arterial supply of the duodenum is via the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery, which is a branch of the gastroduodenal artery, and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, which is a branch of the superior mesenteric artery.

P.202

FIGURE 11-3 Anatomy of the duodenum. The first portion is partially retroperitoneal at its distal margin. The common bile duct and the pancreatic duct empty into the second portion of the duodenum. The third portion runs horizontally to the left and ends to the left of the third lumbar vertebra. At the terminal portion of the fourth portion, the duodenojejunal flexure changes direction sharply and becomes the jejunum. This area of the duodenum is fixed in position by the ligament of Treitz.

2.Venous drainage is via anterior and posterior pancreaticoduodenal venous arcades. These drain into portal and superior mesenteric veins.

C

The layers of the duodenum are the serosa (only on the anterior wall), the muscular layer, the muscularis mucosae, and the mucosa.

1.The muscular layer contains inner longitudinal and outer circular muscle fibers.

2.The mucosa of the proximal duodenum contains Brunner's glands, which secrete a protective alkaline mucus.

IIIGastric and Duodenal Digestion

A

Gastric acid secretion is mediated by a complex interplay of neuronal and hormonal influences. The secretory response during eating is divided into three phases.

1.The cephalic phase is initiated by sight, smell, and thought of food.

a.Vagal stimulation causes parietal cells to secrete acid.

b.Vagal stimulation also causes release of gastrin from the antrum. Gastrin is the most potent stimulator of gastric acid secretion.

2.The gastric phase is initiated by mechanical distention of the antrum. This stimulates additional gastrin release.

3.The intestinal phase of secretion is not well understood. Intestinal factors, such as cholecystokinin, are mild stimulators of acid production.

B

Negative acid feedback mechanisms include a decline in vagal stimulation, increased acid content, and duodenal negative feedback. An antral pH of 2 inhibits gastrin release. Acid chyme in the duodenum stimulates secretin release, which further inhibits gastrin secretion.

P.203

IV Ulcer Disease

A Gastric ulcers

1.Etiology. The etiology of gastric ulcers is multifactorial and not completely delineated. Damage to the gastric mucosal barrier appears to be the most important factor.

a.Reflux of bile into the stomach changes the mucosal barrier, allowing gastric acid to enter the mucosa and injure it.

b.Drugs alter the mucosal barrier to hydrogen ion. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), salicylates, steroids, ethanol, and the combination of smoking and salicylate ingestion are causative agents.

c.Acid secretion is necessary for ulcer formation, but persons with gastric ulcers tend to have lower than normal rates of acid secretion, both basal and stimulated. Their serum gastrin levels, however, are approximately twice the normal levels.

d.Helicobacter Pylori infection is present in more than 80% of patients with gastric ulcers. H. pylori weakens the protective gastric mucous barrier, increases the basal and stimulated concentrations of gastrin, and impedes gastric healing after injury, resulting in gastric ulcer formation.

2.Incidence. Gastric ulcers are more common in men, the elderly, and lower socioeconomic groups. Duodenal ulcers are twice as common as gastric ulcers.

3.Location/Type

a.Type 1 gastric ulcers occur within the body of the stomach, most often along the lesser curve at the incisura angularis along the locus minoris resistentiae. This term refers to the histologic transition zone between the parietal cells of the body and the gastrin-secreting cells of the antrum.

b.Type 2 gastric ulcers occur in the body of the stomach in combination with duodenal ulcers. These ulcers are associated with acid oversecretion.

c.Type 3 gastric ulcers develop in the pyloric channel within 3 cm of the pylorus. These ulcers are associated with acid oversecretion.

d.Type 4 gastric ulcers are located high in the stomach adjacent to the esophagus.

e.Type 5 gastric ulcers are secondary to chronic NSAID and aspirin use and can occur throughout the stomach.

4.Diagnosis

a.History of burning midepigastric pain that is stimulated by or follows eating is a common presentation of gastric ulcers.

b.Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) radiographs will show barium in an ulcer crater.

c.Endoscopy detects 90% of ulcers and allows multiple biopsy samples to be taken to rule out cancer or control bleeding.

d.H. plyori can be confirmed by urease breath test, tissue biopsy, or antibody titer measurement.

5.Gastric ulcers and malignancy

a.A gastric ulcer does not degenerate into carcinoma.

b.Gastric cancer will ulcerate in 25% of cases. It is, therefore, mandatory to prove that the ulcer is not carcinoma; 10% of gastric ulcers are malignancies with ulceration.

6.Treatment

a.Medical treatment of gastric ulcers is indicated initially. Most gastric ulcers will heal in 8–12 weeks.

1.Avoidance of ethanol, tobacco, and drugs that irritate the gastric mucosa is important.

2.Histamine (H2) blockers are effective in healing gastric ulcers. Gastric ulcers associated with NSAID use may not respond as well to H2 blockers.

3.Proton pump inhibitors block the enzyme involved in the parietal cell secretion of acid.

4.Antacid therapy in high doses has been demonstrated to be superior to placebo.

5.Sucralfate is a sulfated sucrose that binds to the ulcer crater and protects for 6 hours.

6.H. pylori treatment reduces the recurrence rates for gastric ulcer. Treatment requires antisecretory agents (omeprazole, etc.), antibiotics (amoxicillin or clarithromycin and metronidazole) and/or bismuth. Ninetypercent cure rates are reported with dual antibiotic and omeprazole treatment.

P.204

b.Surgical treatment is indicated in the following situations.

1.Intractability. The ulcer fails to heal after 8–12 weeks of medical therapy or recurs despite adequate medical therapy.

2.Bleeding not controlled by endoscopy or medical therapy

3.Perforation

4.Gastric outlet obstruction

5.Malignancy cannot be excluded

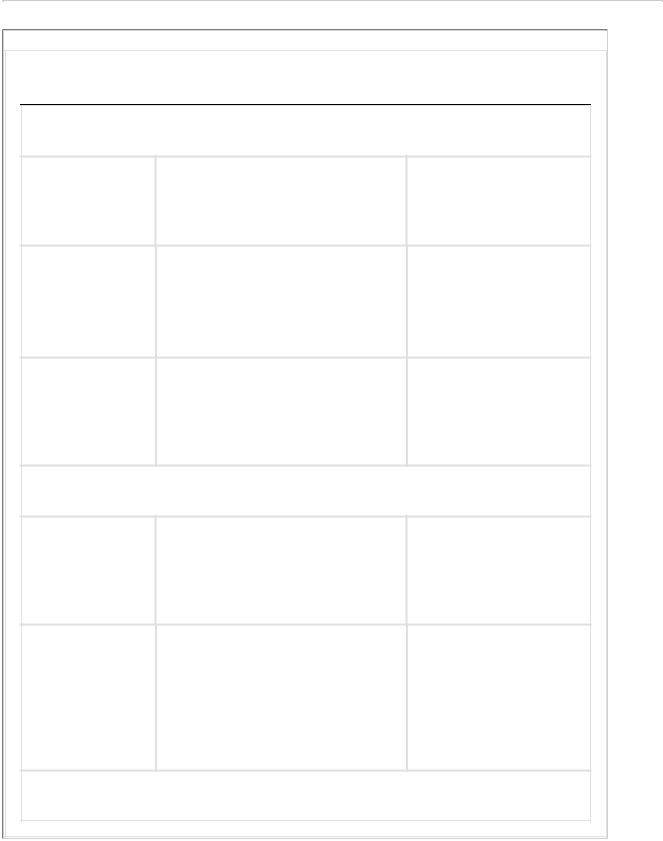

7.Operative procedures (Fig. 11-4). The operative procedure is determined by the type of ulcer, location, and condition of the patient at the time of surgery.

a.Type 1 ulcer

Hemigastrectomy (excision of the distal 50% of the stomach with excision of the ulcer) is historically the procedure of choice.

1.Gastroduodenal anastomosis (Billroth I gastrectomy) is used for reconstruction if the duodenum can be mobilized (Fig. 11-4A).

2.Gastrojejunal anastomosis (Billroth II gastrectomy) is used for reconstruction if the duodenum cannot be mobilized (Fig. 11-4B).

b.Types 2 and 3 ulcers

Vagotomy with antrectomy with extension to include excision of the ulcer. Vagotomy is necessary for pyloric channel ulcers or gastric ulcers occurring with duodenal ulcers in order to reduce acid secretion.

FIGURE 11-4 Common gastric surgical procedures: (A) vagotomy and antrectomy (Billroth I); (B) vagotomy and antrectomy (Billroth II); (C) vagotomy and pyloroplasty; (D) vagotomy and gastrojejunostomy; (E) parietal cell vagotomy; and (F) Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy.

P.205

c.Type 4 ulcer

1.Antrectomy with extension of resection to include the ulcer

2.Antrectomy with wedge excision of the ulcer

d.Type 5 ulcer

Surgical intervention for chemical-induced ulcers is reserved for emergency situations (perforation and hemorrhage). Primary closure, omental patch, or wedge excision combined with cessation of non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs and acetylsaliclyic acid (ASA) are standard treatments.

B Duodenal ulcers

1.Etiology. Peptic ulceration occurs when an imbalance develops between mucosal integrity and acid production.

a.Most, although not all, duodenal ulcer patients experience acid hypersecretion. This condition may be related to an increased mass of acid-secreting cells. The parietal cells in duodenal ulcer patients are more sensitive to gastrin secretion. The feedback inhibition of gastrin release by acid may be impaired in these patients.

b.Mucosal resistance may be altered by bacteria (H. pylori). This gram-negative rod is found in the antrum of 95% of duodenal ulcer patients, and eradication of this organism in patients with ulcers may be therapeutic. Many patients without ulcer disease may have H. pylori.

2.Location

a.Most duodenal ulcers are located in the first portion of the duodenum. Ulcers on the posterior wall may bleed from the gastroduodenal artery. Ulcers on the anterior wall may perforate freely into the abdominal cavity.

b.About 5% of duodenal ulcers are postbulbar, located in the more distal duodenum.

c.Pyloric channel ulcers occur in the gastric antrum within 3 cm of the pylorus and are treated like duodenal ulcers. They frequently do not respond to medical therapy and often require surgery, largely because of the development of gastric outlet obstruction. This results from scarring, inflammation, and stricture formation.

3.Diagnosis

a.History of epigastric pain radiating to the back is the usual presentation. The pain is relieved by food; however, the period of relief becomes shorter as symptoms progress. The pain typically wakes the patient at night.

b.Studies. Esophagoduodenoscopy is the major diagnostic tool. UGI radiographs may also be used.

c.Gastric pH analysis may be used to provide data on acid output in planning for surgery.

d.Serum gastrin level measurements are obtained in patients with recurrent ulceration after surgery, ulcers that fail to respond to medical management, suspected endocrine disorders (MEN I), and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Normal serum gastrin levels are less than 200 pg/mL.

e.H. pylori can be confirmed by urease breath test, tissue biopsy, or antibody titer measurement.

4.Medical treatment of uncomplicated duodenal ulcer disease is usually successful.

a.Avoidance of aspirin, caffeine, alcohol, and tobacco is recommended.

b.Stress reduction may be beneficial.

c.Eradication of H. pylori

d.Pharmacologic therapy is the mainstay of treatment of peptic ulcer disease. H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors are used most commonly for initial treatment and then are decreased to a single bedtime dose for maintenance therapy. Most duodenal ulcers heal in 6–8 weeks with such therapy. Maintenance therapy is recommended because ulcer recurrence after discontinuing medical therapy occurs in 50%–80% of patients (Table 11-1).

5.Surgical treatment of duodenal ulcer is reserved for patients who have ulcers that fail to respond to medical therapy or who have complications, such as perforation or bleeding. There are a number of surgical options. The goal of each is to reduce acid secretion; therefore, most approaches concentrate on interrupting vagal stimulation, antral gastrin secretion, or both.

a.Vagotomy with antrectomy (Fig. 11-4B) is the procedure associated with the lowest recurrence rate.

P.206

TABLE 11-1 Drug Therapy of Peptic Ulcer Disease

|

|

Advantages and |

Agent |

Effect |

Disadvantages |

Decrease Gastric Acidity |

|

|

Antacids |

Neutralize gastric acid; also |

Inexpensive; readily |

|

may increase mucosal |

available |

|

resistance |

|

H2-receptor |

Inhibit histamine receptor on |

Excellent results; |

antagonists |

parietal cell, which decreases |

mainstay therapy; |

(e.g., |

acid output dosing for |

once daily evening |

cimetidine) |

maintenance therapy |

|

Proton-pump |

Inhibit ATP-ase proton pump, |

Quicker healing, but |

inhibitors |

which is final step in acid |

more expensive than |

(e.g., |

secretion from parietal cell |

preceding agents |

omeprazole) |

|

|

Increase Mucosal Defense |

|

|

Cytoprotective |

Binds to proteins in ulcer to |

Not proven for |

topical agent |

form protective mucosal |

gastric ulcers |

(e.g., |

barrier |

|

sucralfate) |

|

|

Antibiotics |

Eradicate H. pylori |

Inexpensive; |

(e.g., |

|

important in |

amoxicillin) |

|

preventing |

|

|

recurrences in |

|

|

patients with H. |

|

|

pylori |

ATP, adenosine triphosphate. |

|

|

b.Vagotomy with drainage is associated with a recurrence rate of 6%–7%. After vagotomy, the motility of the stomach and pylorus is impaired, creating a functional obstruction. For this reason, a drainage procedure, such as a pyloroplasty (Fig. 11-4C) or gastrojejunostomy (Fig. 11-4D), is required.

c.Parietal cell vagotomy (Fig. 11-4E), also known as highly selective vagotomy, is gaining in popularity, especially when the indication for surgical intervention is intractable pain. Only the gastric branches of the vagus nerve are divided. Because innervation of the pylorus is maintained, a drainage procedure is not necessary. Recurrence rates with this procedure are somewhat higher (approximately 10%), but the morbidity is less as compared with truncal vagotomy with antrectomy. This procedure is often performed laparoscopically, further decreasing its morbidity.

6.Complications of ulcers include perforation, hemorrhage, and obstruction.

a.Perforations occur most commonly with ulcers on the anterior surface of the duodenum. Gastric perforations are less common. Occasionally, gastric ulcers can perforate posteriorly into the lesser sac.

1.Signs and symptoms

a.Typical symptoms of perforation include sudden onset of severe abdominal pain, radiation of pain to the shoulder, nausea, and vomiting.

b.Signs include a rigid, boardlike abdomen and shock. An upright chest radiograph frequently demonstrates free air under the diaphragm.

2.Treatment

a.Occasionally, observation may be used if the patient is hemodynamically stable and the initial event occurred several hours previously. A monitored setting, antibiotics, and intravenous fluids are required.

b.Simple operative closure of the perforated ulcer, often with a patch of omentum (Graham patch), is the usual treatment.

c.Definitive treatment of the ulcer (e.g., by vagotomy with antrectomy) may be indicated in low-risk patients with minimal soilage of the peritoneal cavity, especially if they give a long history (more than 3 months) of ulcer symptoms—or proven failure of the medical treatment.

P.207

b.Hemorrhage occurs in approximately 15%–20% of patients with ulcers. Medical management controls the hemorrhage in most cases.

1.Endoscopy is necessary to evaluate the site of the hemorrhage. A “visible vessel” in the ulcer crater is an ominous sign and is associated with a higher risk of rebleeding and a need for surgical intervention.

2.Thermal techniques performed through the endoscope may be effective. These techniques include electrocoagulation, laser, or heater probe.

3.Injection of sclerosing or vasoconstrictive agents may also be used.

4.Surgery. Surgical intervention is usually needed to control massive hemorrhage, defined as blood loss that requires transfusion of more than 1500 mL of blood products without stabilization of vital signs or continued blood loss requiring more than 6 units of transfused blood in a 24-hour period.

a.Techniques

i.Oversewing of the bleeding point is done via a longitudinal opening through the pylorus.

ii.If this fails to control the vessel, it is necessary to isolate and ligate the gastroduodenal artery.

iii.The incision through the pylorus is then closed transversely, which is known as a pyloroplasty, or widening of the pylorus.

b.A truncal vagotomy (division of the two main vagal trunks) is also done to reduce acid stimulation (Fig. 11-4C).

c.Vagotomy with antrectomy is another option in low-risk patients.

c.Gastric outlet obstruction can be caused by prepyloric ulcers and by chronic scarring of the pyloric channel.

1.Symptoms. Obstruction causes symptoms of crampy abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. The stomach is usually markedly dilated. Prolonged vomiting due to obstruction can lead to electrolyte disorders, particularly hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis from the large hydrochloric acid losses.

2.Initial treatment consists of several days of nasogastric suction to allow the stomach to decompress.

3.Surgery. Vagotomy with antrectomy or vagotomy with drainage is the standard procedure.

V Gastritis

A Uncomplicated acute gastritis

1.Etiology. Acute diffuse gastritis can be due to a number of irritating agents, particularly aspirin and ethanol.

2.Hemorrhage can occur and be massive.

3.Treatment. Removal of the inciting agent and antacid therapy usually result in prompt healing.

B

Stress ulceration (acute hemorrhage gastritis) is another form of acute gastritis. Ischemia of the gastric mucosa is the inciting event. The injury is compounded by the effect of the intraluminal acid. Although stress ulceration is common in critically ill patients, only 5% develop significant gastric bleeding.

1.Location. Stress ulcers are characteristically shallow mucosal lesions that start in the fundus. They then spread distally and can involve the entire stomach.

2.Clinical presentation. Affected patients frequently have sepsis, multiple organ system failure, severe trauma, or a complicated postoperative course or are on assisted ventilation. Stress ulceration that occurs in burn patients is known as Curling's ulcer, and stress ulceration occurring in patients with head injury is known as Cushing's ulcer.

3.Treatment

a.Prophylaxis against stress ulceration can be achieved with antacids given as needed to keep the gastric pH above 5. H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors are equally effective at maintaining an adequate gastric pH.

P.208

b.Medical treatment involves correcting the underlying problems (e.g., sepsis) and vigorous use of antacids. Cimetidine is not helpful once bleeding has occurred.

c.Surgical treatment is rarely necessary and is associated with a high mortality. In the case of uncontrollable bleeding, near total gastrectomy is usually the best option.

d.Radiographic embolization can be performed to identify the main artery bleeding and stop blood flow.

VI Gastric Cancer

A Gastric tumors

Approximately 90%–95% of gastric tumors are malignant, and of the malignancies, 95% are adenocarcinomas. Other histologic types include squamous cell, carcinoid, gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), and lymphoma.

B Gastric adenocarcinoma

1.The incidence of gastric adenocarcinoma has been decreasing for many years and is now stabilized. Gastric adenocarcinoma is the tenth most common cancer, with an estimated annual incidence of 22,000 cases and 13,000 deaths. The trend is increasing toward lesions more proximally located in the stomach.

2.Risk factors for gastric cancer include:

a.Age >70 years

b.Diet high in salt, smoked foods, low protein, low vitamins A and C

c.H. pylori infection

d.Previous gastric resection

e.Chronic gastritis and pernicious anemia

f.Blood group A

g.Radiation exposure

h.Tobacco use

i.Male gender

j.Low socioeconomic status

k.Adenomatous polyps

3.Symptoms include epigastric pain, anorexia, fatigue, vomiting, and weight loss. Proximal tumors can present with dysphagia, while more distal tumors may present as gastric outlet obstruction. Symptoms tend to occur late in the course of the disease. Physical signs can include palpable supraclavicular (Virchow's) or periumbilical (Sister Mary Joseph's) lymph nodes.

4.Diagnosis is suggested on UGI radiographs and is confirmed by upper endoscopy with biopsy.

5.Preoperative evaluation may include computed tomography (CT) scan to look for local extension, ascites, and distant metastases. Endoscopic ultrasound has been shown to be useful in determining the depth of penetration and in detecting nodal metastases. Staging laparoscopy may detect small peritoneal metastases and is required before most neoadjuvant protocols.

6.Involvement beyond the stomach may include direct spread to adjacent organs (e.g., spleen, diaphragm, omentum, colon); “drop metastases” to the ovary (Krukenberg's tumor) or the pelvis (Blumer's shelf tumor); or distant disease (e.g., to liver, lung).

7.Classification. Gastric carcinoma is classified according to its gross characteristics.

a.Intestinal type is a well-differentiated, glandular tumor found most commonly in the distal stomach.

b.Diffuse type is a poorly differentiated, small cell infiltrating tumor found most commonly in the proximal stomach.

8.Surgical treatment depends on nodal disease and distant metastases.

a.Potentially curable lesions

1.Potentially curable lesions are treated with subtotal or total gastrectomy, depending on tumor location.

2.Wide margins (>6 cm) on the stomach are necessary because extensive submucosal tumor spread can occur. Lesions of the fundus and cardia may require resection of the spleen, pancreas, or transverse colon to completely remove the cancer.

P.209

3.The role of lymphadenectomy is controversial, but for favorable lesions, there is some advantage to removing the local draining nodes. Removal of the omentum and its nodes is included. Radical lymphadenectomy that includes distant nodal basins has not been shown to improve survival and may increase morbidity. It is recommended that a least 15 regional lymph nodes be sampled to ensure adequate staging of the tumor.

b.Palliative resections are indicated in the presence of obstructing or bleeding gastric cancers. Treatment may include resection, bypass alone, or either one in conjunction with endoscopic or radiotherapeutic techniques.

9.Adjuvant chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil/leucovorin and radiation therapy) after potentially curative resection improves median survival and is the current standard of care. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation is being studied in several clinical trials

but remains unproven at this time. Unresectable tumors may show some response to chemotherapy. The addition of radiation therapy may improve results and can control bleeding symptoms.

10.Prognosis depends largely on the depth of invasion of the gastric wall, involvement of regional nodes, and presence of distant metastases but still remains poor. Overall 5-year survival after the diagnosis of gastric cancer is 10%–20%. Tumors not penetrating the serosa and not involving regional nodes are associated with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 70%. This number decreases dramatically if the tumor is through the serosa or into regional nodes. Recurrence rates after gastric resection are high, ranging from 40%–80%. Potentially curative surgical resection does offer a better 5-year prognosis; however, only 40% of patients have potentially curable disease at the time of diagnosis.

C Gastric lymphoma

The stomach is the most common site of primary intestinal lymphoma; however, gastric lymphoma is relatively uncommon, accounting for only 15% of all gastric malignancies and only 2% of lymphomas.

1.Symptoms are usually vague, namely abdominal pain, early satiety, and fatigue. Rarely ever do patients present with constitutional symptoms (i.e. “B” classification of lymphoma). Patients at risk for developing lymphomas are those who are immunocompromised or are harboring an H. pylori infection.

2.Diagnosis consists of endoscopy with biopsy and endoscopic ultrasound for staging. As with all lymphomas, assessment of distant disease should include bone marrow biopsy; CT of chest, abdomen, and pelvis; as well as an upper airway exam. Testing for H. pylori should also be performed.

3.Treatment consists of a multimodality regimen, with the role of gastric resection remaining highly controversial.

a.Medical treatment combining chemotherapy and radiation is now the most accepted first-line therapy for treating gastric lymphoma. The most common chemotherapy combination is cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin, Oncovin, and prednisone (CHOP). Some variants of lymphoma may also be treated effectively by the eradication of H. pylori infection alone.

b.Surgical treatment is now used mostly for the complications of bleeding and perforation that arise from locally advanced disease. The treatment involves the removal of all gross disease via partial gastrectomy.

4.Prognosis is good, with a 5-year survival greater than 95% when disease is localized to the stomach and 75% when local lymph nodes are involved.

D

Gastric sarcomas arise from the mesenchymal cells of the gastric wall and constitute 3% of all gastric cancers. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are the most common and are found predominately in the stomach.

1.Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) arise from mesenchymal cells of the GI tract, usually the pacemaker cell of

Cajal.

2.Histologic diagnosis is confirmed by immunohistochemical staining for CD 117, a cell surface antigen.

3.Presentation varies from incidental asymptomatic endoscopy or CT findings to symptomatic large tumors causing obstruction, pain, bleeding, or metastases.

4.Treatment is complete surgical removal. Clinical behavior and malignant potential are based on several factors, including mitotic count >5 per 50 high-power fields; size >5 cm; and cellular

P.210

atypia, necrosis, or local invasion. Tumor recurrence or unresectable disease can be treated by imatinib mesylate (Gleevec), which inhibits the c-KIT gene–associated tyrosine kinase receptor responsible for tumor growth. Overall 5- year survival is 50%.

VII Benign Lesions of the Stomach

A

Gastric polyps are usually found incidentally. They often can be excised via endoscopy.

1.Hyperplastic polyps are the most common and arise most often in the setting of chronic atrophic gastritis. These polyps are non-neoplastic, and treatment consists of polypectomy.

2.Adenomatous polyps are associated with a 20% risk of malignancy, especially in those greater than 1.5 cm. Treatment consists of endoscopic polypectomy. Surgery is required for evidence of invasion on polypectomy specimen, for sessile lesions >2 cm, and polyps with symptoms of bleeding or pain.

B

Ectopic pancreas occurs during development and is rare. The majority of cases are found in the stomach, duodenum, and jejunum. The most common presenting symptoms are abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and bleeding. Surgical excision is the recommended treatment.

C

Ménétrier's disease (hypoproteinemic hypertrophic gastropathy) is a premaliganant abnormality of the gastric mucosa with an unknown etiology.

1.Characteristics include the following:

a.A hypertrophic gastric mucosa is seen by radiographic or endoscopic evaluation.

1.Giant rugae are characteristic.

2.Mucous cells are increased in number.

3.Parietal and chief cells are decreased in number.

b.There is gastric hypersecretion of mucus as well as excessive protein loss and hypochlorhydra.

2.Treatment consists of anticholinergics, acid suppression, octreotide, and H. pylori eradication. Total gastrectomy is required in patients with severe hypoproteinemia despite maximal medical therapy.

D

Mallory-Weiss tears are linear mucosal lesions found at the gastroesophageal junction and are related to repeated forceful vomiting. These tears account for 15% of all upper GI bleeds. Massive hemorrhage is rare but is greater in those with preexisting portal hypertension. Most cases of bleeding can be controlled by endoscopic interventions, intra-arterial infusions, or transcatheter embolization. Only 10% of patients require surgery to stop the bleeding, which consists of oversewing the mucosal tear (see Chapter 10, VI).

E

Dieulafoy's gastric lesion is caused by an abnormally large tortuous artery located in the submucosa. The classic presentation is a sudden onset of massive upper GI bleeding with associated hypotension. Endoscopy is both diagnostic and therapeutic. Surgery is rarely needed.

F

Gastric volvulus is an uncommon entity. The volvulus may be intermittent. It is caused by laxity of the ligaments supporting the stomach and is frequently associated with congenital diaphragmatic defects, traumatic injuries to the diaphragm, and paraesophageal hernias.

1.Types

a.Organoaxial volvulus is a rotation around the cardiopyloric line, a line drawn along the length of the stomach between the cardia and pylorus (most common).

b.Mesentericoaxial volvulus occurs around a line perpendicular to the cardiopyloric line.

c.Volvulus may also occur as a combination of these two types.

2.The sudden onset of constant, severe abdominal pain, wretching without vomitus, and the inability to pass a nasogastric tube constitutes Borchardt's triad.

3.Surgical treatment includes reducing the torsion and fixation of the stomach.

G

Bezoars are agglutinated masses of hair (trichobezoars occur most commonly in young, neurotic women), vegetable matter (phytobezoars are seen after a partial gastric resection and

P.211

tend to be more common in older men), or a combination of the two that form within the stomach.

1.Symptoms of a bezoar include nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and abdominal pain. Complications include obstruction and ulceration.

2.Treatment generally requires endoscopic or surgical removal, although enzymatic dissolution of some bezoars has been successful.

VIII Duodenal Tumors

A

Malignant tumors are usually adenocarcinomas. Treatment of resectable lesions is pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple's procedure). Other tumors include carcinoids, GISTs, gastrinomas, and parcomas.

B

Benign tumors include lipomas, benign GISTs, hamartomas, and adenomas. Surgical resection is the treatment of choice.

IX Miscellaneous Disorders of the Stomach and Duodenum

A Gastric outlet obstruction (see IV B 6 c)

B Superior mesenteric artery syndrome Especially in young, thin women, the third portion of the duodenum can be obstructed by the superior mesenteric artery, which takes a sharp angle from the aorta and courses over the duodenum. This anatomic configuration is combined with predisposing factors, such as a lack of the retroperitoneal fat cushion, prolonged immobilization, and pressure (e.g., from a body cast). The syndrome is also known as cast syndrome because of its association with patients in body casts.

1.Symptoms include vomiting and postprandial pain.

2.Treatment

a.Medical treatment consists of eliminating all contributing factors, such as casts, girdles, and lying in the supine position. Weight gain may alleviate symptoms. Increasing oral intake, enteral feeding beyond the ligament of Treitz, and parenteral supplementation may be tried.

b.Surgical treatment includes either releasing the ligament of Treitz, which moves the duodenum out from beneath the superior mesenteric artery, or bypassing the obstruction.

C

Duodenal (pulsion) diverticula are frequently asymptomatic. The most common location is opposite the ampulla of Vater. Severe hemorrhage or perforation can occur; but in the absence of such complications, no treatment is indicated.

X Postgastrectomy Syndromes

These symptom complexes can be disabling.

A

Alkaline reflux gastritis is the most common problem after a gastrectomy, occurring in about 25% of all patients.

1.Symptoms are postprandial epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss.

2.Diagnosis. Endoscopy demonstrates the gastritis and a free reflux of bile.

3.Treatment is conversion of the Billroth I or II gastrectomy (Fig. 11-4A,B) to a Roux-en-Y anastomosis (Fig. 11-4F).

B

Afferent loop syndrome is caused by intermittent mechanical obstruction of the afferent loop of a gastrojejunostomy.

1.Symptoms include early postprandial distention, pain, and nausea, which are relieved by vomiting of bilious material not mixed with food.

2.Treatment consists of providing good drainage of the afferent loop, usually by conversion to a Roux-en-Y anastomosis.

P.212

C

Dumping syndrome affects most postgastrectomy patients but is a significant problem in only a few. It exists in either an early or late form with the former occurring more frequently.

1.Early dumping syndrome occurs within 20–30 minutes following ingestion of a meal. It is more common after partial gastrectomy with Billroth II reconstruction. It results from the rapid movement of a hypertonic food bolus into the small intestine. Rapid fluid shifts into the small bowel cause distention and a subsequent autonomic response along with the release of several humoral agents.

2.Late dumping syndrome occurs 2–3 hours after a meal and is far less common. The large carbohydrate load passed into the small intestine causes on over-release of insulin resulting in profound hypoglycemia. This stimulates the adrenal gland to release a large amount of catecholamines producing confusion tachycardia, lightheadedness and tremulousness.

3.Signs and symptoms may include epigastric fullness or pain, nausea, palpitations, dizziness, diarrhea, tachycardia, and elevated blood pressure.

4.Treatment

a.Conservative nonsurgical measures include octreotide to control symptoms. Patients are advised to avoid a high-carbohydrate diet and not to drink fluids with meals.

b.Surgical treatment is used to delay gastric emptying, including interposition of an antiperistaltic jejunal loop between the stomach and small bowel or conversion to a long limb Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

D

Postvagotomy diarrhea is common in its mild form but seldom is a disabling problem. Symptoms usually improve during the first year after surgery.