- •105) The Deficit dilemma

- •106) Deficits, Surpluses, and the Balanced Budget

- •107) Why are large deficits so bad?

- •108) Defining surpluses and debt

- •If a government collects more in taxes than it spends, it has a government budget surplus.

- •109) Differentiating between the Deficit and the Debt

- •110) Difference Between Individual and Government Debt

105) The Deficit dilemma

The Triffin dilemma or paradox is the conflict of economic interests that arises between short-term domestic and long-term international objectives when a national currency also serves as a world reserve currency. The dilemma of choosing between these objectives was first identified in the 1960s by Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin. He pointed out that the country whose currency, being the global reserve currency, foreign nations wish to hold, must be willing to supply the world with an extra supply of its currency to fulfill world demand for these foreign exchange reserves, and thus cause a trade deficit.

The use of a national currency, e.g., the U.S. dollar, as global reserve currency leads to tension between its national and global monetary policy. This is reflected in fundamental imbalances in the balance of payments, specifically the current account: some goals require an overall flow of dollars out of the United States, while others require an overall flow of dollars into the United States.

Specifically, the Triffin dilemma is usually cited to articulate the problems with the role of the U.S. dollar as the reserve currency under the Bretton Woods system.

106) Deficits, Surpluses, and the Balanced Budget

Government Budget Surplus and Deficit

If a government collects more in taxes than it spends, it has a government budget surplus.

If a government spends more than it collects in taxes, it has a government budget deficit

Budget balance = Receipts – Outlays

If receipts exceed outlays, the government has a budget surplus.

If outlays exceed receipts, the government has a budget deficit.

If receipts equal outlays, the government has a balanced budget

Government in the Market for Loanable Funds

A

Government Budget Surplus

A

Government Budget Surplus

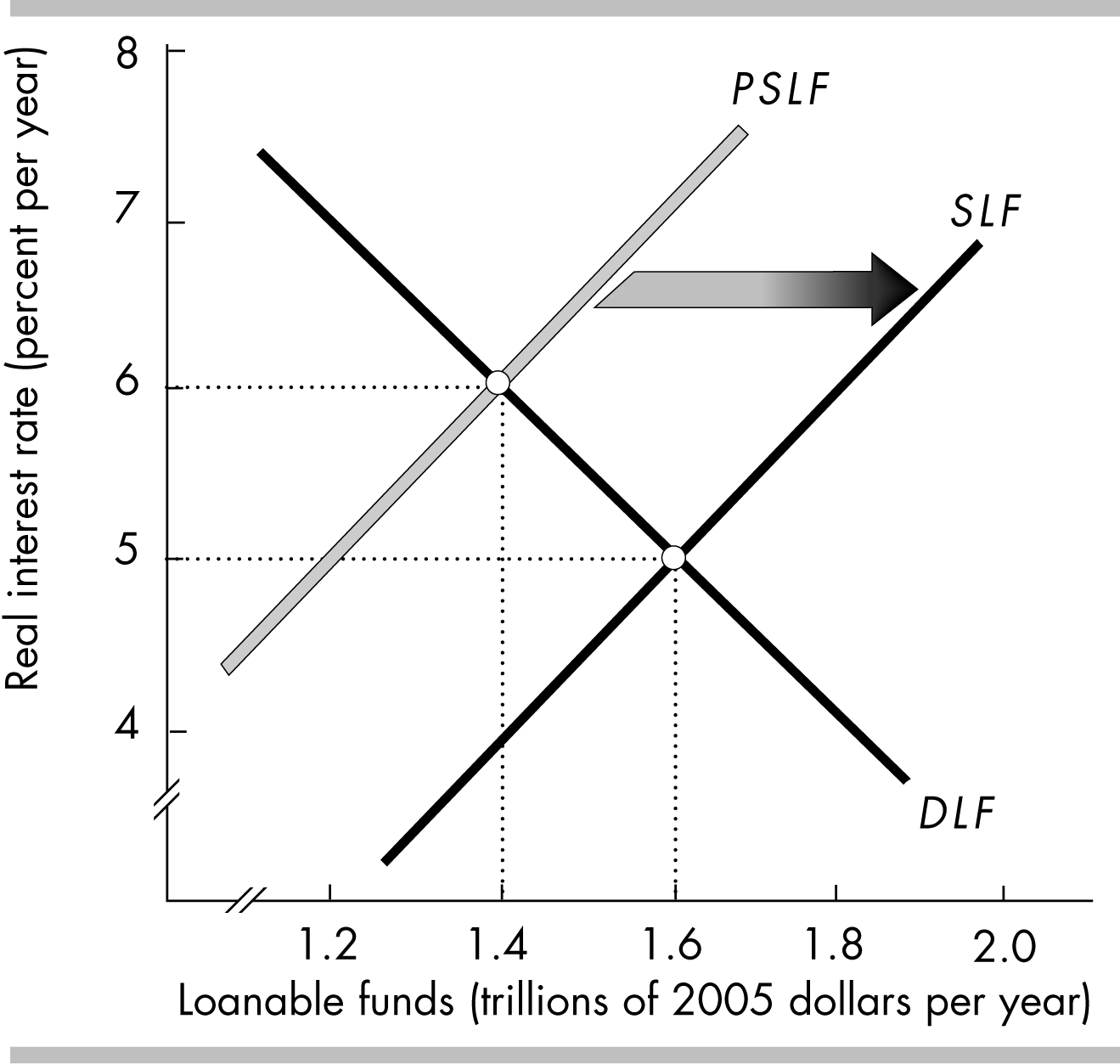

Changes in the government surplus can shift the supply of loanable funds curve. In the figure, PSLF is the private supply of loanable funds curve. The government has a budget surplus equal to the length of the arrow ($0.4 trillion). The surplus adds to private saving and so the supply of loanable funds curve becomes SLF. Without the budget surplus, the real interest rate is 6 percent and the quantity of loanable funds and investment is $1.4 trillion; with a budget surplus, the real interest rate is 5 percent and the quantity of loanable funds and investment is $1.6 trillion.

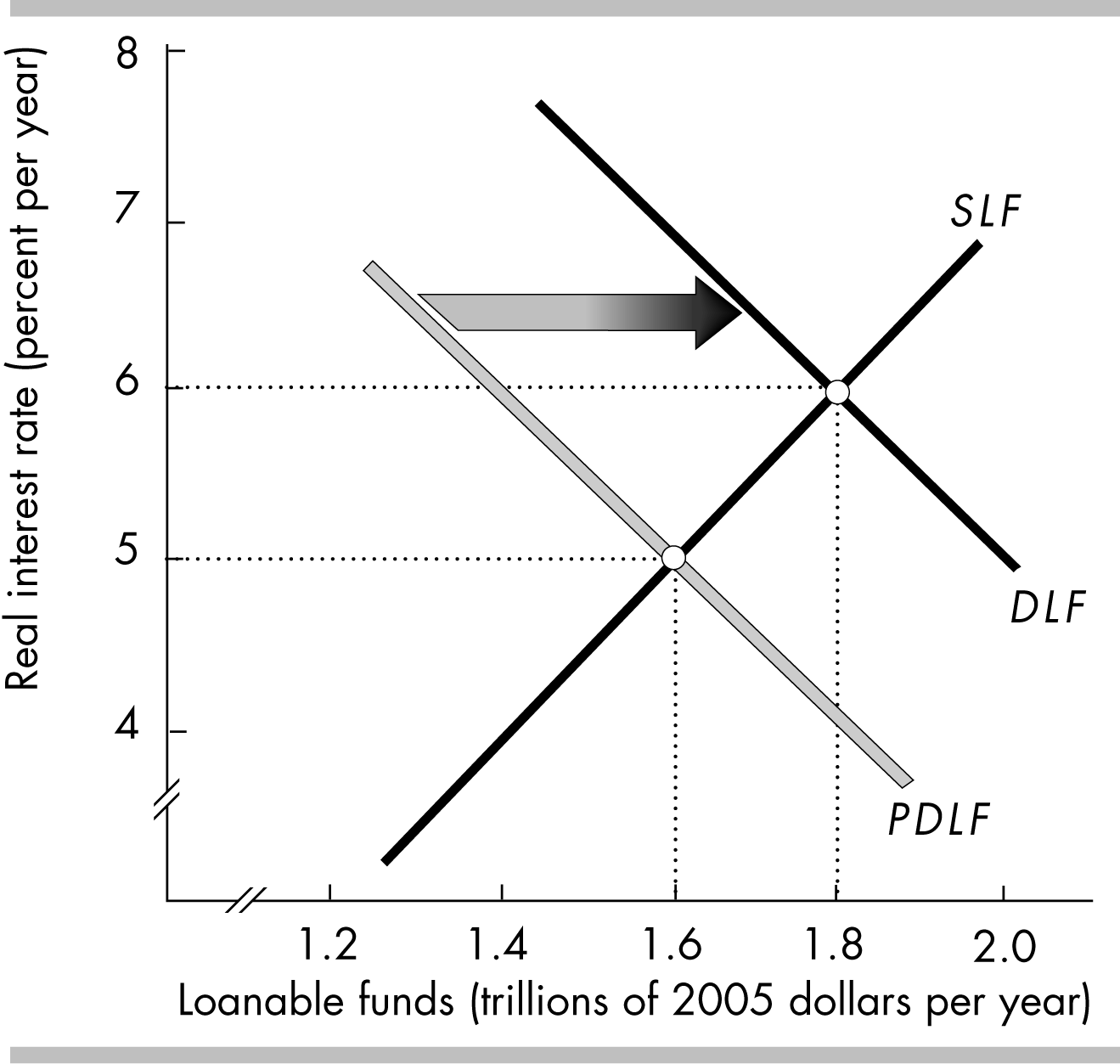

A Government Budget Deficit

Changes

in the government deficit can shift the demand for loanable funds

curve. In the figure, PDLF

is the private demand for loanable funds curve. The government has a

budget deficit equal to the length of the arrow ($0.4 trillion). The

deficit adds to private demand and so the demand for loanable funds

curve becomes DLF.

Without the budget deficit, the real interest rate is 5 percent and

the quantity of loanable funds and investment is $1.6 trillion; with

the budget deficit, the real interest rate is 6 percent, the

quantity of loanable funds is $1.8 trillion, and investment is $1.4

trillion.

Changes

in the government deficit can shift the demand for loanable funds

curve. In the figure, PDLF

is the private demand for loanable funds curve. The government has a

budget deficit equal to the length of the arrow ($0.4 trillion). The

deficit adds to private demand and so the demand for loanable funds

curve becomes DLF.

Without the budget deficit, the real interest rate is 5 percent and

the quantity of loanable funds and investment is $1.6 trillion; with

the budget deficit, the real interest rate is 6 percent, the

quantity of loanable funds is $1.8 trillion, and investment is $1.4

trillion.The tendency for a government budget deficit to decrease investment is called a crowding-out effect.

The possibility that a budget deficit increases private saving supply in order to offset the increase in the demand for loanable funds is called the Ricardo-Barro effect. The reasoning behind this effect is that taxpayers will save to pay higher future taxes that result from the deficit. To the extent that the Ricardo-Barro effect occurs, it reduces the crowding-out effect because the SLF curve shifts rightward to offset the deficit.