- •Содержание

- •Природное наследие астраханского края

- •Археология нижнего поволжья

- •Астраханский край в XVI-XXI вв.

- •Социокультурное взаимодействие народов астраханского края

- •Культурное наследие астраханского края

- •Природное наследие астраханского края

- •Музейные коллекции в.А. Хлебникова

- •Морфология и генезис пещер возвышенности биш-чохо

- •Морфометрические характеристики пещер возвышенности Биш-чохо. (по данным на 01.01.2010 г.)

- •Библиографический список

- •О результатах карстологических исследований на возвышенности биш-чохо

- •Библиографический список

- •Еще раз о мамонте

- •Находка скелета бизона (bison priscus) близ с. Косика енотаевского района астраханской области

- •Череп ископаемого сайгака (saiga borealis) из палеонтологической коллекции астраханского музея-заповедника

- •К вопросу о развитии отечественной орнитологии и астраханской орнитологической школы в советский период. (обзор литературы)

- •Библиографический список

- •Начальные пути реализации программы развития туризма в астраханской области

- •Туристско-ресурсный потенциал волго-ахтубинской поймы

- •Влияние агпз на здоровье человека

- •Библиографический список

- •Музей ооо «газпром добыча астрахань» и поддержание коммуникаций в области сэм и смот и пб

- •Археология нижнего поволжья

- •Предметы эпохи поздней бронзы из астраханского заволжья

- •Библиографический список

- •О датировке городища мошаик

- •Библиографический список

- •История изучения погребальных памятников эпохи раннего и развитого средневековья на территории Астраханского края

- •Библиографический список

- •Композиционные и технологические особенности орнаментации поливной керамики самосдельского городища

- •Библиографический список

- •Могильники Селитренного городища: статистическая характеристика

- •Библиографический список

- •Селитренное городище - раскоп XXII. Ориентация вымостки и реконструкция колонны памятника

- •Библиографический список

- •Приложение

- •Керамика из последней загрузки горна мастерской № 9 селитренного городища

- •Библиографический список

- •Средневековые энколпионы, найденные в окрестностях астрахани

- •Библиографический список

- •Приложение

- •Геофизические исследования на селитренном городище

- •Пулы маджарской чеканки на селитренном городище

- •Библиографический список

- •Инвестиционный проект по созданию и комплексному развитию (музеефикации) историко-археологического и природно-ландшафтного музея-заповедника «великая степь» (рабочий вариант)

- •Приложение

- •Астраханский край в XVI-XXI вв.

- •Взаимоотношения ногайцев с астраханским ханством в XV–XVI вв.

- •Библиографический список

- •Тайша мончак и русско-калмыцкие отношения в середине 1660-х гг.

- •Библиографический список

- •«Служилые» и центральная власть московской руси - астрахань как типичный опорный пункт XVI – XVII вв.

- •Библиографический список

- •Буддийская община приволжских калмыков во взаимодействии калмыцого ханства с циньской империей, джунгарским ханством и тибетом в XVII- начале XVIII вв.

- •Библиографический список

- •Библиографический список

- •Значение астрахани в системе международных отношений россии со странами средней азии в XVII – XVIII вв.

- •Библиографический список

- •Переписка астраханских губернаторов с калмыцкими ламами в XVIII в.

- •Библиографический список

- •Безопасность колонии сарепта в 1771 – 1774 гг.

- •Библиографический список

- •Проекты религиозных реформ астраханского губернатора и.С. Тимирязева в отношении приволжских калмыков

- •Библиографический список

- •Роль секретаря губернского статистического комитета в организации научных исследований астраханского края

- •Библиографический список

- •Астраханское армянское агабабовское училище

- •Библиографический список

- •Органы городского самоуправления в формировании материальной базы внешкольного образования во II половине XIX в. (на материалах нижнего поволжья)

- •Библиографический список

- •Горчичная промышленность колонии сарепта, и её влияние на традиционное хозяйство населения нижнего поволжья в XIX – начале XX вв.

- •Библиографический список

- •Старейшие лечебные заведения астраханской губернии (конец XVIII – нач. Хх вв.)

- •Библиографический список

- •Астраханский механический завод товарищества «братья нобель»

- •Библиографический список

- •«За заслуги перед городом»

- •Библиографический список

- •История губернской фотографии (1860-1920гг.).

- •Библиографический список

- •Февральская революция 1917 г. В астраханском крае

- •Библиографический список

- •Началовские события: кулацкий мятеж или крестьянское восстание

- •Библиографический список

- •Городская повседневность: жизнь и смерть трамвая в астрахани

- •Библиографический список

- •История развития села удачное ахтубинского района астраханской области

- •Библиографический список

- •К истории формирования местных органов управления советской власти (на примере татаробашмаковского сельсовета)

- •Библиографический список

- •Идентификация астраханского региона как субъекта пограничного взаимодействия

- •Библиографический список

- •Правда и домыслы в астраханском краеведении

- •Библиографический список

- •Восстановить историческую справедливость даты основания города астрахани

- •Библиографический список

- •Еще раз о происхождении астраханских татар (ответ на статью р.У. Джуманова «Был ли «Интерстадиал» у населения Хаджи-Тархана (Астрахани) в середине XVI в.»)

- •Библиографический список

- •К истории астраханских ногайцев

- •Библиографический список

- •Приложение

- •Родо-племенной состав жителей села татарская башмаковка в XVIII-XX вв.

- •Библиографический список

- •Приложение

- •( С XVII- XX вв.) на бугре «Кос-Тюбе»

- •Трансформация родоплеменных сообществ юртовцев (караийле) в семейно-клановые группы в современности

- •Кулинарные традиции ногайцев-карагашей

- •Культурное наследие астраханского края

- •Драконы, города и «строительные жертвы»: об астраханско-казанских фольклорных параллелях

- •Библиографический список

- •«Арифметика» л. Магницкого и воспитание торговой культуры

- •Библиографический список

- •Новые сведения о становлении театра а.К. Грузинова в астрахани (1809-1818 гг.)

- •Библиографический список

- •Иван акимович репин и его библиотека глазами вячеслава ивановича склабинского

- •Из Репинской библиотеки

- •Творческая деятельность абдул-хамида джанибекова

- •Библиографический список

- •Музейные мероприятия – проводники культурного наследия прошлого (о праздниках горожан дореволюционной Астрахани)

- •Государственная политика в области развития школьного театра в первое десятилетие советской власти (1917-1927 гг.) в нижнем поволжье

- •Библиографический список

- •Музею на улице ульяновых – 40 лет

- •«Семья хлебниковых» (комплект медалей)

- •Библиографический список

- •Традиции и инновации в области народного творчества: социологический аспект

- •Библиографический список

- •Литературная карта города (кон. XX – нач. XXI вв.)

- •Исследовательская краеведческая деятельность школьников как средство изучения культурного наследия астраханского края и эколого-нравственного образования и воспитания подрастающего поколения

- •Библиографический список

- •Приложение

- •Роль музея в возрождении духовно-нравственного воспитания молодежи в современной россии

- •Библиографический список

- •Сведения об авторах

Приложение

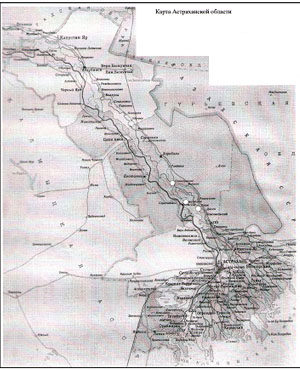

Рис.1.Карта Астраханской области с обозначением памятников, находящихся на территории Харабалинского района.

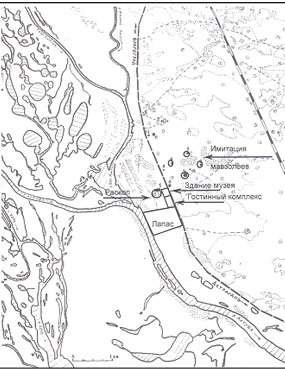

Рис.2. План-схема Селитренного городища с размещением музейных объектов.

Рис.3. Схема расположения музейного комплекса у пос. Лапас.

Астраханский край в XVI-XXI вв.

Arno Johannes Langeler

University of Amsterdam, Netherlands

DUTCH AND RUSSIAN CARTOGRAPHERS AND DESIGNERS, WINIUS, WITSEN AND OTHERS

Lately, I noticed a doctorate dissertation written by the Dutchman Igor Wladimiroff, De kaart van een verzwegen vriendschap, Nicolaes Witsen en Andrej Winius en de Nederlandse cartografie van Rusland, ( the map of a concealed friendship, Nicolaes Witsen and Andrej Winius and the Dutch cartography of Russia), Groningen 2008. This book seems to me as very important for clearing some relations between The Netherlands and Russia in the 17th and the beginning of the 18th centuries. The author, a descendent of Russian emigrants, has composed an interesting and enlightening book, written in a very readable style. Immediate cause for his writing was the beautiful Russian map of Nicolaes Witsen, mayor of Amsterdam and “devotee cartographer”,drawn in 1687 and published in 1689: De Nieuwe Landkaarte Van het Noorder en Ooster deel van Asia en Europa Strekkende van Nova Zemla tot China Aldus getekent, Beschreven, in Kaart gebragt en uytgegeven sedert een nauwkeurig onderzoek van meer als twintig jaren door Nicolaes Witsen. Anno 1687 ( A new map from the northern and eastern part of Asia and Europe, stretching from Nova Zembla to China, Drawn, written, mapped and edited after a precise investigation of more than 20 year by Nicolaes Witsen. In the year 1687 - see plate 30 in the book of I.Wladimiroff). Because it never became completely clear how Witsen acquired the bulk of the materials necessary for his map of parts of the world that he never visited and a rumour existed that Andrej Winius provided him with some materials, Wladimiroff decided to investigate the relations between Witsen and Winius.

Cartography and some Dutchmen in Russia in the 16th and 17th century

In the first place Wladimiroff paints a picture of the Dutch mercantile contacts with Russia and the influence of their cartography in that respect. Some influence of the Flemish and Dutch activities was attributed to contacts between historian, and medic Paolo Giovio and the ambassador of grand-duke Vasilij III the translator and diplomat Dmitrij Gerasimov who paid a visit to pope Clemens VII in 1525. From the hand of Giovio was the outcome of this encounter the Novocomensis Libellus de Legatione Basilii Magni Principis Moschoviae (the new booklet from Como about the embassy of grand-duke Vasilij) . A map showing Russia was separately edited based on the notices of the Roman Plinius the Elder, suggesting that it was possible to sail from the White Sea through the Arctic to China (1).

The first people from the Low Countries travelling in 1565 from Antwerp to the north of Russia were Philips Winterkoning and Cornelis de Meyer(e) (a distant ancestor of my wife Betty)(2). After the fall of Antwerp to the Spaniards, the mercantile activities of many inhabitants shifted to the new Republic of the United Netherlands, in this case to the northern provinces.

The maps got better and better. After the conquest of the port of Narva by the Swedes in 1581 English and later Dutch ships found their way to the new city of Archangel on the White Sea. A lot of cartographic activities in the Dutch Republic accompanied the mercantile movements. Dutch merchants got in the end the upper hand over the English in Russia. In the relations between the Moscovites and the Dutch, the in Russia active native from Haarlem Isaäc Massa and several Russian embassies to the General States of the Republic and to stadtholder prince Maurits played a significant role. Wladimiroff mentions here the intermediate function of the Amsterdam mayor Gerrit Witsen, an early relative of Nicolaes (3).

The preponderance of foreigners in Russia in commercial matters evoked some xenophobic sentiments. This was for the Dutch an negative factor because some measures to limit the trade of wheat, threatened the Dutch dependency of the grain import from Russia. A Dutch embassy to tsar Michaïl in 1631 to obtain a monopoly on Russian grain export had no success. After the death of Michaïl the situation for foreign merchants worsened. Special envoys did not attain noticeable success. An example of these was the embassy led by Jacob Boreel that visited Moscovia and Moscow in 1664 and 1665. The young Nicolaes Witsen took part in this embassy, wrote a diary and made some remarkable drawings of spots he passed on his way to Moscow (4).

The silk trade was very important to the Dutch. For that reason they sent in 1675 Coenraed (van) Klenck to the tsar. He knew that the attempt of the Russians to establish in Astrachan their own trading post with Persia was shattered through the uprising of Stepan Razin, and therefore he came with the request to explore by the Dutch a new way through Siberia to Persia and China. His second demand was a Russian participation in the war against Sweden – an ally of the French who were in that time in a state of war with the Republic. In spite of the confidence and hospitality Klenck enjoyed at the Russian court, he went home with empty hands. Main reasons were the distaste to grant foreign merchants special privileges and the unwillingness of the tsar to wage war with Sweden(5).

Russia in Dutch cartography

To the foremost Dutch cartographers in the 17th century belonged the family Blaeu, three generations, manufacturing maps and atlases in Amsterdam. Wladimiroff refers to the Atlantis Appendix of Willem Blaeu with maps of Moscow and the Kremlin, made around 1630. He says: “ The source of that map of Moscow was to all probability the ….inset map of tsar Boris Godounov….The plan of the Kremlin is without doubt from Russian origin and had been possibly taken along by Massa”(6). These maps were in 1665 also published in the Atlas Major by his son Joan Blaeu, with for the Kremlin extensive explanation. Very interesting is in this atlas the river chart of the Volga. This map was based on a chart, made by the German Adam Olearius, who in 1633 paid a visit to Russia as member of an embassy sent by the duke of Holstein to the tsar. A few years later he organized an expedition to the South East in the direction of Persia in order to trade with that country. Due to a bad preparation this enterprise failed(7). Wladimiroff mentions the cooperation between Olearius and a certain Cornelis Kluyting, a Dutchman. In 1636 Kluyting got permission from tsar Michaïl to act as a pilot on the ship that carried Olearius across the Volga to the Caspian Sea. Kluyting was not only a sailor, but also a technician. He assisted Olearius in mapping the Volga and its estuary into the Caspian. Later, in 1658, only after the publication of Olearius’s diary in the Republic, the cartographer Jan Jansz. Janssonius edited Nova et Accurata Wolgae fluminis, olm Rha dicti delineation Auctore Adamo Oleario (a new and accurate map of the river Volga, of old called the Rha, by the hand of Adam Olearius). The same map was published in the Atlas Major and used for corrections by Nicolaes Witsen on his journey to Moscovia.

The next person that appears in Wladimiroff ‘s description of important Dutch maps of Russia is Jan Struys. “Under the command of Butler and skipper Lambert Jacobsz. Struys (she) sailed.across the Volga and the Caspian Sea in the direction of Persia. Along the way, however, the Orel , near Astrachan, was taken by the rebel leader Stenka Razin. Struys got into captivity, but escaped later”(8). Here Wladimiroff was somewhat inaccurate: the crew of the Orel was partly inside Astrachan where she was taken prisoner by Razin during the capture of the city. Some tried to escape before the final attack of the Cossacks on the city. The Orel deprived of heir cannons laid defenceless on the quayside and got destructed – at which moment exact is not known (9).

Annex to Struys’s travel report was a Zee Kaert Verthonende de Kaspische Zee (sea chart showing the Caspian Sea) (10).

Witsen

Nicolaes Witsen made his personal acquaintance with Russia through his voyage to Moscow in 1664 and 1665. His Diary shows how greatly that country had him impressed. In Moscow he was able to make a lot of observations: about the looks and behaviour of tsar Aleksej and the common people, the appearance of the Kremlin, the housing, the religion and the administration of the law. Witsen was assisted by Andrej Winius, his second cousin, interpreter for the tsar and member of the posolskij prikaz. However, in his diary Witsen never mentions his name, but only refers to a friend who was very helpful to him. The leader of the Dutch embassy, Boreel, records several occasions where Winius acted as interpreter (11).

After his return to Amsterdam, Witsen stayed the rest of his life interested in Russia, not only in political and economic matters, but also in the geography in that country. First, he made, following many others of his class, a grand tour through Europe: he visited Paris, Lyon, Milan, Florence and Rome. He returned via France and Cologne. After the death of his father Cornelis in 1669, Witsen was obliged to gain – in the tradition of his family - his own position in the city administration of Amsterdam. In 1672, the Dutch Year of Wonders, he was put in charge of the defence of the city during the invasion of the French and two German bishops. Somewhat later he became one of the mayors and assisted in 1688 and 1689 politically stadtholder William III in his Glorious Revolution in England (12).

Besides his work as administrator of Amsterdam. Nicolaes Witsen spent a lot of time on his investigations. The books published by him give some evidence of his exertions. The first of them, Aeloude en Hedendaegsch(z)e Scheepsbouw en Bestier (Old and Present Shipbuilding and Steering) appeared in 1671. The price of the book was 12 guilders, a considerable amount. In his foreword Witsen utters his amazement that no earlier book on ships and their equipment had been published in his maritime country. The Scheepsbouw en Bestier was a rather popular work; “from Sweden to Italy and from Moscovia to Batavia one could find copies in the libraries of wealthy scholars, notwithstanding the fact that the work was written in the Dutch language. Proof for the popularity turns up from the letters of the German savant Gottfried Leibniz and from the well-known diplomat and poet Constantijn Huygens who evoked the interest of the English king Charles II.- for us a remarkable fact; in that time a full war was going on between England and the Dutch Republic.(13 There was some criticism on several passages in the book. In his description of the battle between the Dutch and the Swedes in the Oresund (1658), Witsen stated that the Swedish admiral, count Karl Gustav Wrangel had deserted the battle because he was hit by a bullet in his jaw “however his ship was named the Victoria”. Wrangel, in possession of the Scheepsbouw and Bestier was furious, because his ship was so damaged that he was not able to continue the fighting, In a letter, he complained to Witsen, with result. The author changed some pages: he named Wrangel manhaft (brave) and his son who was killed in that battle a hero. In reaction thereupon Wrangel called Witsen an honnête home (14)

In a short time, the book was a antiquarian rarity. In 1690 a second appeared edited by the firm Pieter and Joan Blaeu, a fact that was only discovered in the beginning of the 20th century. Wladimiroff is very restricted on Scheepsbouw en Bestier. Marion Peters, on the other hand, introduces in her The wijze koopman (see n.13) a lot of sketches of ship types – mostly made by Nicolaes Witsen himself. This goes for Dutch and foreign vessels alike. The edition of 1690 contains the Russisch-Vaar-tuigh (Russian vessel),a special and new part of chapter 16 of part 1 with 7 images of Russian ships - made by anonymous artists.(15 Witsen had collected a lot of Russian materials and illustrations for his Noord en Oost Tartarije (North and East Tartary), published in 1692, second edition in 1705 and long after his death in 1785.

A new edition of Noord en Oost Tartarije is forthcoming, so I restrict myself to some cartography in his work. Already, during his visit to Moscow, Witsen had a conversation with Gerrit Kluyting about the geography of the Caspian Sea and the surrounding area’s. Witsen was allowed the make a copy of the map of the Caspian region made by Kluyting’s brother Cornelis. Later, he inserted this map in his Diary and became known as the Het Caspise Meer....Na de origineele Teeckningh, in Mosco afgemaeckt. Ao 1665. Nicolaus Witsen (The Caspian Lake….After the original drawing, in Moscow copied. In the year 1665. Nicolaus Witsen (16).

Wladimiroff enumerates a number of maps in both the editions of Noord en Oost Tartarije. Several of them were designed by Witsen himself, other were copies from already existing charts – sometimes mistakenly attributed to himself. In this respect is map 3 important: Het suydelykste gedeelte van de Vliet Wolga in Kaert gebragt volgens de jongste verbeteringe van den Heer E.Kempfer, uit de miswysinge van’t Compas en andersints gerigt, door N.Witsen, Cons.Amst. MDCXCVII. (The most southern part of the river Volga, mapped according to the most recent improvements of mr. E.Kaempfer, as consequence of the false indications of the compass, and (therefore) directed in another direction, by N.Witsen, mayor of Amsterdam, 1697. This means that this map was not taken down in the first edition of 1692. This Kaempfer , a German, medic and collector, was secretary to the Swedish envoy Lodewijk Fabricius, from birth a Dutchman, who travelled in 1683 through Russia to the Sjah of Persia in Isfahan. He was a friend of Witsen’s. “Under the authority Kaempfer worked as a correspondent for Witsen” (17).

Another map – not in the first edition – is Nieuwe kaert vande omtrek der Swarte Zee uyt verscheydene stucken van die gewesten toegezonden, ontworpen door N.Witsen, Cons:Amste. MDCXCVII. (A new map of the outline of the Black Sea, sent from various parts of those regions, designed by N.Witsen, mayor of Amsterdam. !697. Wladimiroff sees a similarity with older Italian maps. In 1723 made the Amsterdam publishers Ottens a copy of Witsen’s map (18).

In the first edition one can find Palus Maeotis, in kaartgebragt door N.Witsen, MDCXC.( The sea of Azov, charted by N.Witsen, 1690. The name Palus Maeotis is derived from Ptolemaeus. The exact source is not known; there are many examples for this map.(19

Winius

Cousin and one of the dearest friends of Nicolaes Witsen in Russia was Andrej Andrejevitsj Winius. He, the son of the Dutch merchant in Russia and therefore because of his knowledge of the Dutch language, was acting as interpreter for the tsar. So he came in contact with foreign diplomats. In 1665 he met Witsen. Working as an interpreter brought Winius also in contact with the Dutch shipbuilders in Dedilovo on the Oka that were constructing two vessels for sailing the Volga and the Caspian Sea. Wladimiroff speaks about a frigate, but the greatest of the two was probably a pinas. On this way, the Russians hoped to control the profitable trade with Persia. The Dutch gostj Jan van Sweeden advised the tsar to hire a Dutch crew. First, he got the commitment of the General States of the Republic, thereafter, captain David Butler – a Dutchman – was sent to Amsterdam, where he recruited 15 artisans and sailors (20).

After 1689, the year in which Peter became the actual ruler of Russia, Winius became one of the intimates of the tsar. He was nominated as postmaster-general and got in correspondence with the tsar about things like shipbuilding, the war in the Southern Netherlands against the French where Witsen was active as delegate of the States and about a big fire in the main iron foundry in Sweden – important for the production of cannon for France. Witsen was the source of this topic. The embassy of tsar Peter to West Europe was announced in the end of 1696; Winius should stay in Moscow for reason of communication with Peter. Wladimiroff mentions a letter from Peter, written in Riga, to Winius: “....keep this letter above a fire – it is written in invisible ink – and you can read it….But to avoid suspicion, I shall write on the same paper with normal ink”(21).

Winius’s relations with Witsen were intensified by his cartographic activities. Around 1689 Andrej Winius drew a map of Siberia on base of sketches of the road from Moscow to Peking made by the envoy Nicolae Spathary-Milescu, who travelled in 1675 on behalf of tsar Fjodor to the emperor of China. In 1695 Winius became head of the Sibirskij prikaz. As such, he had to accomplish his charting of the vast space of Siberia. The goal was in the first place an economic. The opening up was meant for indicating new roads that were suitable for trade with adjacent countries and for defining the border regions. In the chart-room of the Sibirskij prikaz in Moscow were besides maps of Siberia the most famous atlases available, Ortelius, Mercator and Blaeu. Winius worked together with the cartographers Remezov, father Uljan and sons Leontij and Semjon (22). In 1701 Winius and Semjon Remezov published their Tsjertjoznaja Kniga Sibiri – two of the copies are known with the Dutch title Caertboek van Siberië. One came in the Netherlands and was named in the legacy of Nicolaes Witsen. After the auction in 1761 of the books of Witsen, during which the book was described as Een vertaling (translation) van het Groot Sibirs Caartboek; the atlas have not been heard of since. The second copy lies in the Public Library in Moscow (23). One can assume that a lot of data and peculiarities on Siberia were borrowed by Witsen from Winius for his second edition of Noord en Oosr Tartarije in 1705.

In 1703 Andrej Winius lost for what reasons the grace of tsar Peter. Relations between Witsen and Winius remained good. Proof of that fact one can find in letters that Witsen wrote to Winius. Also gifts bear witness of their mutual cordiality. A example of this concerns Reizen over Moskovië door Perzië en Indië, verrykt met 300 konstplaten....(Travels over Muscovy through Persia and India, enriched with 300 artificial plates), Amsterdam 1711 of Cornelis de Bruyn (1652 – 1726/1727. This work was completed in cooperation with Nicolaes Witsen. Around 1712 Witsen presented this book to Winius. Notable to say that in 1722 the editor Gerard van Keulen copied the “Panorama of Astrachan” of de Bruyn as illustration to his Nieuwe Caart van de Caspische Zee....(New map of the Caspian Sea), mainly based on the map of Jan Struys (24).

Marion Peters mentions that Winius stayed in Amsterdam from 1706 till 1708. According to Witsen’s friend Gijsbert Cuper, mayor of the city of Deventer who visited Witsen in 1711, Winius fled to Amsterdam “three or four years ago” after losing all his estates and dignities. Witsen wrote a letter to the tsar and Mensjikov and his intervention had “un tres bon effet”. Winius got mercy and received his confiscated estates (25).

Around 1709, tsar Peter gave his ambassador in the Dutch Republic, Andrej Artamonovitsj Matvejev assignment to order the newest map of Russia, made by the Frenchman Guillaume de L’Isle. In that period, the Amsterdam publishers Jean Covens and Corneille Mortier revealed his Carte de Moscovie, consisting of two parts. This was a sign of the decreasing influence of Witsen and Winius for the cartography of Russia. Another signal was Matvejev’s assignment to explore the possibility of printing a new atlas consisting of 80 maps of all empires of Russia, replacing the Atlas Major made 50 years earlier by Blaeu. The project never came to existence, probably because the Russian authorities supposed the costs too high (26).

Finally

“There is no doubt that Nicolaes Witsen and Andrei Winius have worked together”. Wladimiroff sees as the main obstruction to this observation that they kept their cooperation secret by not mentioning each other’s names in their letters till the reforms and openness of tsar Peter. Before that, Witsen was surely dependent on Winius for preparing his maps on Russia and in particular Siberia and his Noord en Oost Tartarije. The data on Siberia were kept secret – by naming Winius as his source, Witsen could ruin him (27). The friendship between the two men was solid).

Important books in this article

Igor Wladimiroff, De kaart van een verzwegen vriendschap, Nicolaes Witsen en Andrej Winius en de Nederlandse cartografie van Rusland, Groningen 2008, Baltic Studies 10, ISBN 978-90-812859-1-9 , copyright Igor Wladimiroff en het Instituut voor Noord- en Oost-Europese Studies.

In the rear of the book are 53 maps and drawings, some in the possession of mr.Wladimiroff:

No.11 map of Tartaria by Jodocus Hondius

No.17 map of Russia by Isaäc Massa

No.24 map of the river Wolga by Adam Olearius

No.25 map of the Caspian Sea

No.26 map of the Caspian Sea with Astrachan by Jan Jansz. Struys made in 1668

No.36 map of Siberia to China Tartaria sive Magni Chami Imperium by Nicolai Witsen

No.37a new map of the Russian Empire by Nic. Witzen dedicated to Imperatori Petro Alexewitz

No.44 map of the Caspian Sea by Carl van Verden in the year 1719,1720 and 1721

No.53 map of Muscovy and Siberia Magnae Tatariae Tabula – Carte de Tartarie by Guillaume de L’Isle published in Amsterdam

Marion Peters, De wijze koopman, het wereldwijde onderzoek van Nicolaes Witsen (1641 – 1717), burgemeester en VOC-bewindhebber van Amsterdam, Amsterdam 2010, ISBN 978-90-351-341-2-6, copyright Marion Peters.

In chapter 5 one can find a lot of information about Witsen’s Scheepsbouw en Bestier, his maps and Noord en Oost Tartarije. She reproduces images of ancient ships (in the editions of 1671 and 1692), views on a jolly, a fluyt and a galleon (in the 1692 edition, the Architectura Navalis ) and foreign vessels (both editions).

The bulk of the books of Nicolaes Witsen such as Scheepsbouw en Bestier and Noord en Oost Tartarije should be available in the main archives and public libraries in Russia. The same goes for his cartographic labour.

Notes

1) For Dmitrij Gerasimov see A. Langeler, Maksim Grek, Byzantijn en humanist in Rusland (Maksim Grek, Byzantine and Humanist in Russia), Amsterdam 1986, pp.146 – 148. For old descriptions of the Caspian Sea , the Don, other rivers and the mountains of the Caucasus see Plinius the Elder, Natural History, Book 6, vi – v.

2) For their adventures see Jan Willem Veluwenkamp, Archangel, Nederlandse ondernemers in Rusland 1550 – 1785 (Archangel, Dutch entrepreneurs in Russia 1550 – 1785), Maastricht 2000, pp.23 – 25. It came to my notice that some years ago an edition in Russian translation has been published. On the cover of the Dutch edition one can see two unarmed fluyts in the port of Archangel.

3) I. Wladimiroff, De kaart van een...., pp.21 – 23.

4) ibidem, pp.29 – 30 noticed some progress, see also Nicolaes Witsen, Moscovische Reyse 1664 – 1665. Journaal en Aantekeningen (Voyage to Moscow, diary and annotations 1664 – 1665 - in the text and the annotations called the Diary) ed. by Th.J.G. Locher and P. de Buck, 3 vol., The Hague 1966 – 1967. For the drawings see A.N. Kirpichnikov, Rossia XVII veka v risunkach i opisaniach gollandskogo putesjestvennika Nikolaasa Vitsena, St.Peterburg 1995,

5) I. Wladimiroff, De kaart van een....,pp.32 – 33.

6) ibidem, p.95.

7) ibidem, p.95, Olearius published his map of the Volga as annex to his diary Vermehrte Moscowitische und Persianische Reisebeschreibung (1647). In my possession is a Dutch translation by Dirck van Wageninge made for Jacob Benjamin, bookseller in the Raamsteeg (steeg = alley), Amsterdam 1651, without the map showing the Volga (see the text), but proving the popularity the work by the many translations in several languages. See also The Travels of Olearius in 17th-Century Russia, translated and edited by Samuel Baron, Stanford 1967.

8) ibidem, p.106.

9) For an account of the events around Astrachan see Struys’s own description in The perillous and most unhappy voyages of John Struys....To which are added 2 narratives sent from Capt. D.Butler, relating to the taking in of Astrachan by the Cosacs, London 1683. In the same year of the appearance of Wladimiroff’s book (2008) Kees Boterbloem published The Fiction and Reality of Jan Struys, A Seventeenth Century Dutch Globetrotter, New York, based on Struys’s ventures. Obviously, Wladimiroff and Boterbloem were not informed about each other’s research.

10) In the possession of the author – Collectie Wladimiroff nr. 910309,illustration 26.

11) I.Wladimiroff, De kaart van een....,p.131. This omgedoopte (= converted to the Russian Orthodox belief) friend that pointed Witsen on several mistelinge (mistakes) made by Olearius, pp.131 – 132. At the end of his Diary Witsen enumerates them. On p.134 Wladimiroff provides the reader with a rather flat description of Witsen’s secret visit to patriarch Nikon in his New Jerusalem monastery in Istra. According to the Diary Witsen poked around in the main church, the Voskresenskij sobor, during a short absence of Nikon. He compared the buildings of the monastery with the estate Franckendael in the Watergraafsmeer, a polder in Amsterdam. He showed by this a typical Amsterdam nosey behaviour. Wladimiroff does not mention the Verbael (account) of the embassy made by Boreel for the General States of the Dutch Republic.

12) ibidem, pp.138 – 139. For a connexion between William and Witsen since 1672, see Steve Pincus, 1688, The First Modern Revolution, Yale 2009, p.314. King of England, William offered Witsen a baronet; he refused.

13) Marion Peters, De wijze koopman.Het wereldwijde onderzoek van Nicolaes Witsen (1641 – 1717), burgemeester en VOC-bewindvoerder van Amsterdam (The wise - savant - merchant, The world-wide investigation of Nicolaes Witsen (1641 – 1717), mayor and VOC-administrator of Amsterdam), Amsterdam 2010, p.152 and p.441.

14) ibidem, pp.158 – 159.

15) ibidem, pp. 164 – 165, I.Wladimiroff, De kaart van een....,p153 – 154.

16) I.Wladimiroff, De kaart van een....,p.159, Diary, vol.III, 473.

17) ibidem, p.168. For the adventures of Lodewijk Fabricius during and after the taking of Astrachan by Stenka Razin, see A.G.Man’kov, Zapiski inostrancev o vosstanii Stepana Razina, Leningrad 1968, pp.14 – 46.

18) I.Wladimiroff, De kaart van een...., p.168 – 169, the map of 1723 is in the private collection Wladimiroff, nr.850501.

19) ibidem, p.169.

20) ibidem, p.222. Wladimiroff mentions the names of the sailmaker and adventurer Jan Struys and Karsten Brand(t), able seaman and gunner, who should later the young tsar Peter teach the principles of shipbuilding. His source for this is Boris Raptschinskij, Peter de Groote in Holland 1697 – 1698, Zutphen 1925, pp.30 – 33. For the difficulties defining a pinas, see one of my earlier notifications.

21) I.Wladimiroff, De kaart van een....,pp.230 – 231. The iron foundry in Sweden belonged probably to the family De Geer.

22) ibidem, pp.254 – 256.

23) ibidem, pp.256 – 257, illustration 52, fasc. copy of the frontispiece with added Dutch translation, Public Library Moscow, fond 256, no.346, l. 23. Winius fell into disgrace by manipulations of Aleksandr Danilovitsj Mensjikov, a good friend of tsar Peter.

24) ibidem, pp 249 and .282 – 283. M Peters, De wijze koopman,...p.106, the book was sent to Winius “with the fleet”.

25) M.Peters, De wijze koopman...., p.105 and n. 18.

26) I.Wladimiroff, De kaart van een....,pp.269 – 270.

27) ibidem, pp.277 and 346.

Д.С. Кидирниязов

Институт истории, археологии и этнографии Дагестанского научного центра РАН