- •Examination questions for discipline Microeconomics

- •Production Efficiency

- •The ppf and Marginal Cost

- •Markets and Prices

- •The law of demand

- •The Factors that Influence the Elasticity of Supply

- •New Ways of Explaining Consumer Choices

- •Consumption Possibilities

- •Work-Leisure Choices

- •The Firm and Its Economic Problem

- •Markets and the Competitive Environment

- •Product Curves

- •Short-Run Cost

- •Marginal Cost and Average Costs

- •Marginal Cost and Average Costs

- •The Long-Run Average Cost Curve

- •Perfect competition

- •What is Perfect Competition?

- •The Firm’s Output Decision

- •Output, Price, and Profit in the Short Run

- •Price Discrimination

- •Marginal Revenue and Elasticity

- •63. Single-Price Monopoly and Competition Compared

- •Monopoly Regulation

- •Monopolistic Competition and Perfect Competition comparison

- •What is Oligopoly?

- •Two Traditional Oligopoly Models

- •Oligopoly Games: An Oligopoly Price-Fixing Game

- •Antitrust Law

- •Classifying Goods and Resources

- •Public Goods

- •Common Resources

- •The Anatomy of Factor Markets

- •The Demand for a Factor of Production

- •Capital and Natural Resource Markets

- •Nonrenewable Natural Resource Markets

- •Property Rights and the Coase Theorem

- •Achieving an Efficient Outcome

Capital and Natural Resource Markets

Capital rental markets and land rental markets can be understood using the same basic ideas from the competitive labor market.

Markets for nonrenewable natural resources are different.

Capital Rental Markets

The demand for capital is equal to the value of the marginal product of capital, and equilibrium in the market for capital occurs where the value of the marginal product of capital is equal to the rental rate of capital.

Whether a firm rents or buys capital depends on a comparison of the cost of a purchase relative to the stream of rental costs incurred over some future period. The Mathematical Note develops this result and the concept of present value.

Land Rental Markets

The demand for land is based on the value of marginal product of land, and equilibrium in the market for land occurs where the value of the marginal product is equal to the rental rate of land.

The supply of land is fixed, so the supply curve is vertical.

Nonrenewable Natural Resource Markets

Oil, gas, and cola are examples of nonrenewable natural resources that are used to produce energy.

The demand for oil is determined by the value of the marginal product of oil and the expected future price of oil. Changes in the expected future price of oils is a speculative influence on demand. The opportunity cost for a trader of buying and holding oil is the interest rate that could be earned as an alternative.

The supply of oil is determined by known oil reserves, the scale of current oil production facilities, and the expected future price of oil. The marginal cost of extracting oil increases, which results in an upward-sloping supply curve for oil.

The market fundamentals price of oil is determined by the value of marginal product of oil and the marginal cost of extraction.

Speculative forces based on expectations of the future price also can affect the current price. When expectations are revised so that the price is expected to be higher in the future, the current demand increases and the current supply decreases. Speculation can drive a wedge between the equilibrium price and the market fundamentals price.

The Hotelling Principle states that traders expect the price of a nonrenewable natural resource to rise at a rate equal to the interest rate. The actual path of a nonrenewable natural resource will not necessarily rise at this rate because the actual path depends on exploration and technological changes.

Property Rights and the Coase Theorem

Property rights are legally established titles to the ownership, use, and disposal of factors of production and goods and services that are enforceable in the courts. Assigning property rights can reduce the inefficiency arising from an externality.

The Coase theorem is the proposition that if property rights exist, if only a small number of parties are involved, and if the transactions costs are low, then private transactions are efficient. Transactions costs are the opportunity costs of conducting a transaction

A remarkable feature of the Coase theorem is that it does not matter if the property right is given to the creators of the externality (the polluters) or to the victims. In either case, the result will be efficient.

If the polluters value the benefits from the activity generating the pollution more highly than the victims value being free from the pollution, (that is, the cost of reducing the pollution exceeds the benefit from the reduction) then the efficient outcome is for the pollution to continue. If polluters are assigned the right to pollute, the victims are not able to pay enough to convince the polluters to stop. If the victims are assigned the property right to be free from pollution, then the polluters are able to pay the victims sufficient compensation to continue polluting. Either way, the pollution continues.

If the victims value the benefits from being free from pollution more highly than the polluters value the benefits of the pollution, (that is, the benefit from reducing pollution exceeds the cost of the reduction) then the efficient outcome is for the pollution to stop. If the polluters are assigned the right to pollute, then the victims are willing to pay the polluters sufficient compensation to stop the pollution. If the victims are assigned the right to be free from pollution, then the polluters are not able to pay the victims enough to allow them to continue polluting. Either way, the pollution stops.

Government Actions in the Face of External Costs

There are three main methods that the government uses to cope with external costs:

Taxes

The government can set a tax equal to the marginal external cost. The effect of such a tax is to make marginal private cost plus the tax equal to marginal social cost:

MC + Tax = MSC.

This tax is called Pigovian Tax, in honour of the British economist Arthur Cecil Pigou, who first proposed dealing with externalities in this fashion.

Emissions Charges

The government sets a price per unit of pollution, so that the more a firm pollutes, the higher are its emissions charges. For the emissions charge to induce the firm to generate the efficient level of pollution, the government would need a lot of information that is usually unavailable.

Marketable Permits

Each firm is assigned a permitted amount of pollution per time period, and firms trade permits. The market price of a permit confronts polluters with the social marginal cost of their actions and leads to an efficient outcome.

Positive Externalities: Knowledge

Knowledge as well as research and development can create external benefits. Arts and sporting participation: visiting museums and theatres can increase knowledge. The external benefits of increased knowledge are hard to quantify, but probably important. Sporting participation will lead to a healthier nation and improve team-working skills.

Marginal external benefit

Marginal private benefit (MB = D) – It’s the benefit from an additional unit of a G & S that the consumer of that G & S receives.

Marginal external benefit – It’s the benefit from an additional unit of a G & S that people other than the consumer of the G & S enjoy.

Marginal social benefit

Marginal social benefit (MSB) – It’s the marginal benefit enjoyed by society – by the consumers of a G & S and by everyone else who benefits from it. It’s the sum of marginal private benefit and marginal external benefit.

Government Actions in the Face of External Benefits

To avoid the deadweight loss or to achieve a more efficient allocation of resources in the presence of external benefits the government does the following

Public provision – It’s the production of a G or S by a public authority that receives most of its revenue from the government.

Private Subsidies . Subsidy – It’s a payment that the government makes to private producers that depends on the level of output.

Voucher – It’s a token that the government provides to households that can be used to buy specified G or S.

Intellectual property rights – It’s the property rights of the creators of knowledge and other discoveries.

Patent or copyrights – It’s a government-sanctioned exclusive right granted to the inventor of a G, S, or productive process to produce, use, and sell the invention for a given number of years.

An Overfishing Equilibrium

With a common resource, to decide whether to fish, each boater compares his or her marginal private benefit from fishing to the marginal cost of fishing. Each boater’s marginal private benefit is the average catch of fish.

The table has an example of these calculations. The first two columns show the number of boats and the total catch. The third column calculates the average catch per boat. This column and this calculation are the marginal private benefit from fishing, that is, the MB. The last column gives the marginal catch from each boat. This column and calculation gives the marginal social benefit from the boat, that is, the MSB.

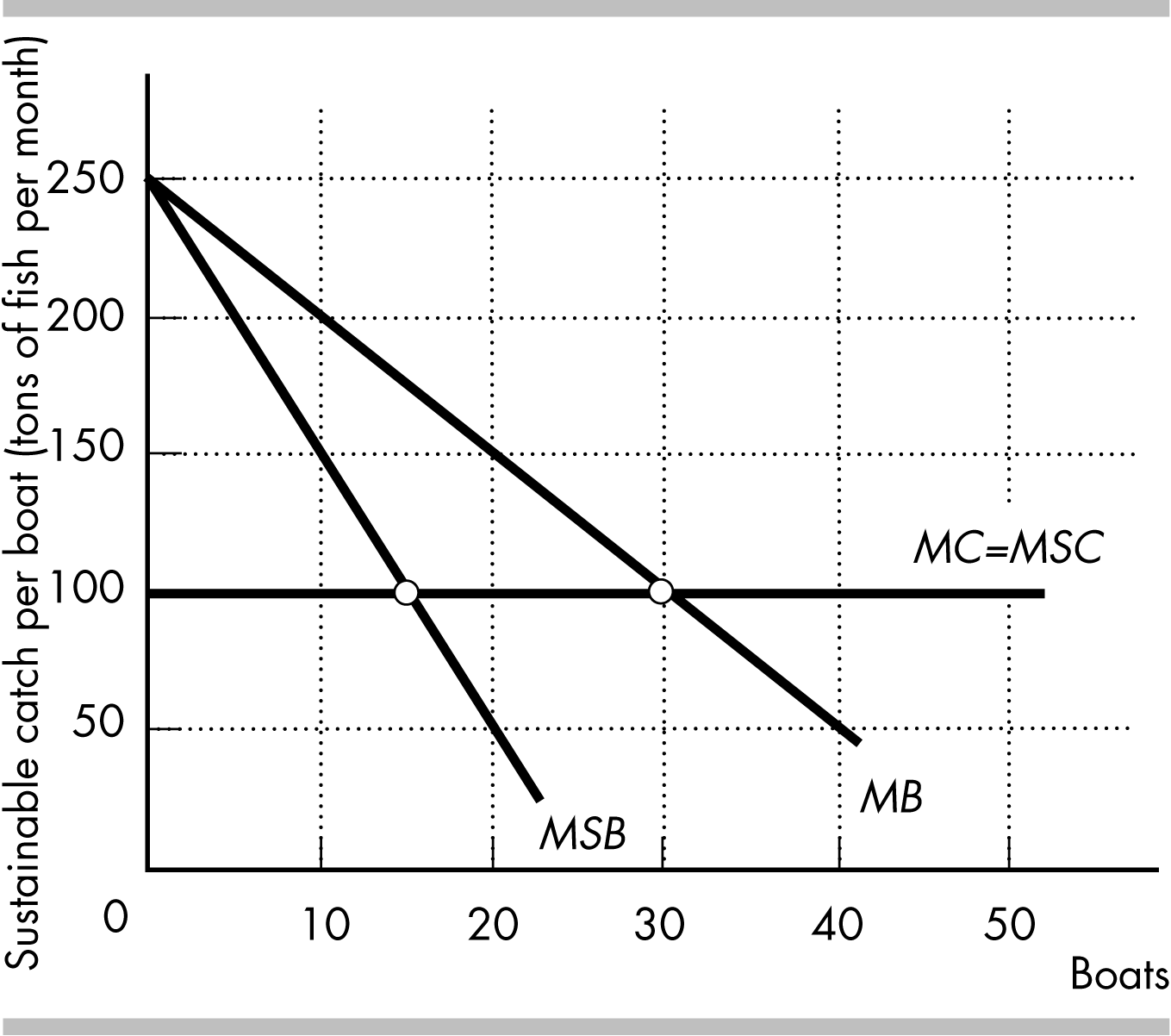

T he

figure plots the numbers from the table. In the figure, the marginal

private benefit curve is MB

and is the average catch schedule from the table above. The private

equilibrium is where the marginal private benefit equals the marginal

social cost. If the marginal social cost is equivalent to 100 tons of

fish, the private equilibrium has 30 boats fishing. The total catch

is 3,000 tons, the total cost is 3,000 tons (30 boats

100 tons per boat cost), and the net catch is 3,000 tons

3,000 tons = 0 tons. Overfishing occurs because the net catch is

zero.

he

figure plots the numbers from the table. In the figure, the marginal

private benefit curve is MB

and is the average catch schedule from the table above. The private

equilibrium is where the marginal private benefit equals the marginal

social cost. If the marginal social cost is equivalent to 100 tons of

fish, the private equilibrium has 30 boats fishing. The total catch

is 3,000 tons, the total cost is 3,000 tons (30 boats

100 tons per boat cost), and the net catch is 3,000 tons

3,000 tons = 0 tons. Overfishing occurs because the net catch is

zero.

The marginal social benefit of a boat is the boat’s marginal catch—-the increase in the total catch that results from an additional boat. The table calculates the marginal social benefit (marginal catch schedule) and the figure graphs this as the MSB curve. The efficient equilibrium is where the MSB equals the MSC. At the efficient equilibrium, the quantity of boats is 15. The catch per boat is 175 tons, for a total catch of 2,625 tons. The total cost of 15 boats is 1,500 tons (15 boats 100 tons per boat) so the net catch is 2,625 tons 1,500 tons = 1,125 tons.