- •Examination questions for discipline Microeconomics

- •Production Efficiency

- •The ppf and Marginal Cost

- •Markets and Prices

- •The law of demand

- •The Factors that Influence the Elasticity of Supply

- •New Ways of Explaining Consumer Choices

- •Consumption Possibilities

- •Work-Leisure Choices

- •The Firm and Its Economic Problem

- •Markets and the Competitive Environment

- •Product Curves

- •Short-Run Cost

- •Marginal Cost and Average Costs

- •Marginal Cost and Average Costs

- •The Long-Run Average Cost Curve

- •Perfect competition

- •What is Perfect Competition?

- •The Firm’s Output Decision

- •Output, Price, and Profit in the Short Run

- •Price Discrimination

- •Marginal Revenue and Elasticity

- •63. Single-Price Monopoly and Competition Compared

- •Monopoly Regulation

- •Monopolistic Competition and Perfect Competition comparison

- •What is Oligopoly?

- •Two Traditional Oligopoly Models

- •Oligopoly Games: An Oligopoly Price-Fixing Game

- •Antitrust Law

- •Classifying Goods and Resources

- •Public Goods

- •Common Resources

- •The Anatomy of Factor Markets

- •The Demand for a Factor of Production

- •Capital and Natural Resource Markets

- •Nonrenewable Natural Resource Markets

- •Property Rights and the Coase Theorem

- •Achieving an Efficient Outcome

Monopolistic Competition and Perfect Competition comparison

Monopolistic Competition and Perfect Competition

Unlike firms in perfect competition, firms in monopolistic competition have excess capacity and a markup:

Excess Capacity: A firm has excess capacity if it produces less than its efficient scale, the quantity that minimizes its average total cost. In the long run, a firm in perfect competition produces at the minimum ATC but, a firm in monopolistic competition produces less than the quantity that minimizes the ATC.

Markup: A firm’s markup is the amount by which its price exceeds its marginal cost. A firm in perfect competition has no markup but a firm in monopolistic competition charges a price that is greater than its marginal cost of production.

What is Oligopoly?

The distinguishing features of an oligopoly are the presence of natural or legal barriers that prevent the entry of new firms and so only a small number of firms compete.

Barriers to Entry and Small Number of Firms

A natural oligopoly market occurs when the efficient scale of production allows only a few firms to meet the market demand. A duopoly is an oligopoly market with two firms.

Because there are a small number of firms, the firms in an oligopoly market are interdependent—each firm’s profit depends on its actions and the actions of its competitors. The firms have a temptation to form a cartel, which is a group of firms acting together—colluding—to limit output, raise price, and increase economic profit. Such collusion is illegal in the United States but it still occurs.

Examples of Oligopoly

Examples of oligopoly include cigarettes, batteries, and automobiles.

Two Traditional Oligopoly Models

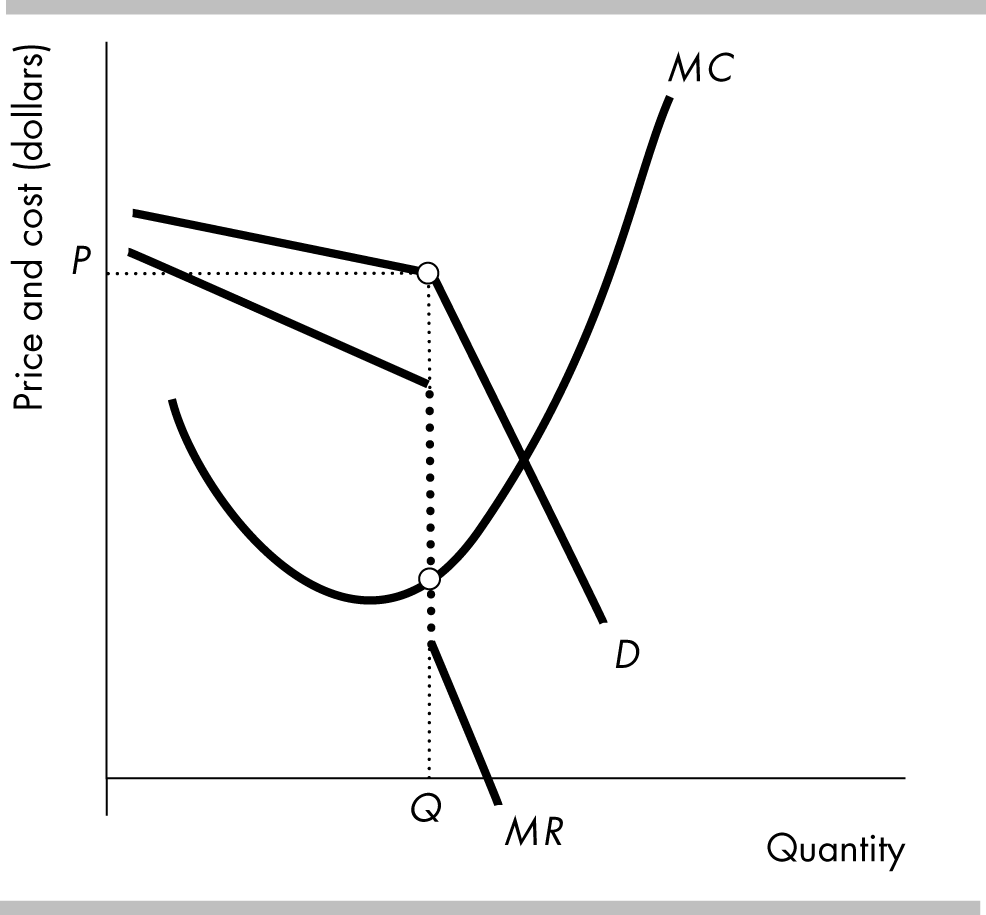

Kinked Demand Curve Model

The figure illustrates the kinked demand curve model. The demand curve is kinked at the current price and quantity. Demand is relatively elastic above the kink because the firm assumes that if it raises its price, no other firm will change its price. Demand is relatively inelastic below the kink because the firm assumes that if it lowers its price, all the other firms will lower their prices. The kink creates a break in the marginal revenue curve.

Small changes in marginal cost lead to no changes in the price and quantity. But large changes lead all firms to change their prices and quantities, at which point the initial firm realizes its initial beliefs were incorrect.

Dominant Firm Model

There is one large firm producing a large part of the industry output because it has a cost advantage over the other, smaller firms. The small firms act as perfect competitors, taking as given the market price set by the dominant firm. The large firm operates as a monopoly, using as its demand the excess demand not met by the smaller firms.

Oligopoly Games: The Prisoners’ Dilemma

All games share four common features: rules, strategies, payoffs, and outcome

In the prisoner’s dilemma, the rules specify that each prisoner is placed in a separate room and must choose whether to confess without conferring with his accomplice.

Strategies are all the possible actions of each player.

The game’s payoff matrix, a table that shows the payoffs for every possible action by each player for every possible action by each other player, is above. In it are the payoffs from each prisoner’s strategies, which are to confess or deny involvement in the serious crime.

The choices of both players determine the outcome of the game. We use the concept of a Nash equilibrium to predict the outcome of a game.

A

rt (A) and Bob (B) have been caught stealing cars. Both men are sentenced to two years in jail for this crime. Both are suspected of committing a more serious crime for which the prosecutor has insufficient evidence for a conviction. The two men are each interrogated for the more serious crime in separate cells. Each prisoner is told that if he confesses and his partner denies, he will serve 1 year in jail and his partner will serve 10 years, while if both confess, both serve 3 years. If neither confesses, each man will spend 2 years in jail, after being convicted of a lesser crime.

The Nash equilibrium for the prisoners’ dilemma is for both players to confess.