- •Monetary Policy of Reserve Bank of New Zealand

- •Introduction

- •Literature review

- •New Zealand. Economic and political structure in brief.

- •The Reserve Bank of New Zealand

- •Analysis and Interpretation of Data

- •Graph №11 – New Zealand Official Cash Rate (ocr)36

- •Conclusion and a look forward

- •List of references

New Zealand. Economic and political structure in brief.

Background: New Zealand is a small country of only 4.5 million people (that is less than one half of the Moscow city). It relies in large part on agriculture, which is also its main export item. New Zealand is actively trading with the USA, Australia, UK, Japan and China, as well as with other East and South-East Asian countries. Some economic statistics are given in the table below13:

-

GDP in 2012 (USD billion)

169.7

GDP per head (USD at market exchange rates)

37,869

Historic average GDP growth (2008-2012)

1.0%

Inflation

2.7%

Public debt (USD billion)

71.2

Public debt as % of GDP

46.5%

The country is focusing on reconstruction efforts after the devastating Christchurch (Canterbury region) in February 2011. There was a significant loss of life and a lot of damage to property caused by this earthquake. The Government sees its job in strengthening the state finances, improving the country’s economic performance and productivity and the environment of regulation. Many previously state-owned assets are now being privatized. The taxation level is relatively low, with personal income taxes starting at 10.5% and the top rate of 33%. This is similar to the United States, but lower than the top marginal tax rates in the Continental Europe (over 50%) or the United Kingdom (45%). The indirect taxation is represented by GST (Goods and Services Tax, the equivalent of VAT) at the standard rate of 15% on final purchases of goods and services. This level is above the sales taxes in most states of the USA, but lower than the Value-Added Tax in most European Countries and Russia.

Major exports are dairy products (25%), meat products (11%) and forestry items (9%). The leading export markets are Australia, China and the USA. Major imports are machinery (20%), mineral fuels (18%) and transport equipment (12%), and the country mainly imports from the same partners, although in imports China takes first place, Australia second, and the US – third.

Political structure: New Zealand is part of the Commonwealth of Nations and is a democratic state. The latest government was formed following the November 2011 general election, by the Prime Minister, John Key. The political and social environment is stable with no major turmoil expected over the foreseeable future. The Prime Minister is widely expected to hold on to his job at the next general elections, although, as with many other countries, the Government regularly faces criticism from the Opposition.

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ as it may be referred to hereafter in this work) will be 90 years old in 2014. It operates under the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act of 1989. It is owned by the Government but is independent from the Government in making the monetary policy decisions.

The Bank’s current Governor is Mr. Graeme Wheeler. He replaced the previous Governor, Mr. Alan Bollard, in September 2012.

It is written in the law that “…the primary function of the Bank is to formulate and implement monetary policy directed to the economic objective of achieving and maintaining stability in the general level of prices”14. The main mechanism through which the bank conducts the monetary policy is the Official Cash Rate (OCR). This rate is set to influence the interest rates in the market in the short term. The Bank can lend overnight funds at 0.25 per cent above the OCR to banks, and on the other hand, the Reserve Bank can take deposits from banks at OCR less 0.25 per cent. The Bank has no limit on how much it can borrow or lend in the market at these rates. This creates a good mechanism to ensure that the level of the interest rates in the market is as close to the OCR as possible.

Adjustments to the official cash rate are made eight times a year. There is no obligation on the Bank to change the Official Cash Rate at any time. On the other hand, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand can make unscheduled adjustments, but does not usually do so unless in really exceptional circumstances.

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand is also responsible for, and engages in, macro-prudential regulation. This is a broader role and is aimed at taking measures to preserve wider economic stability (for example, to hold back economic risk-taking in good times, to prevent appearance of asset price bubbles, or to improve standards of performance by the country’s banks15.

The Bank has long subscribed to the view that its functions in the economic system should be limited to those, where it is naturally the most competent agent to provide direction and regulation – the financial and banking system. The policy tools which the Bank considers should be regularly used, are also standard – mainly the policy rate adjustments and general banking supervision. In other words, the Bank considers its role as specific.

This view and policy making attitude have been subject to a growing criticism from the group of economists who subscribe to alternative views. These views were recently restated by Thomas I. Palley in his Working Paper for the German Macroeconomic Policy Institute No 8/2011. The institution most criticized was the Federal Reserve of the United States, however, it is evident that most Central Banks (including the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England) and the monetarist theory in general are all targets of this criticism.

Mr. Palley’s and his colleagues’ view is that the current rethink of monetary policy and central banking (called the “insider rethink”) does not go far enough as it only scratches the surface of the problems which culminated in the Financial Crisis of the late 2000s. In particular, the argumentation is as follows:

There is already a reform proposal (the “insider rethink” mentioned just above), but this proposal does not mean a change in macroeconomic theory;

The actions of many of the Central Banks, including the Federal Reserve, during the crisis are justified16;

The focus of the “insider rethink” is narrow – namely, (a) monetary policy and asset price bubbles; (b) regulation in monetary policy; and (c) zero limit to the nominal interest rate17.

Finally, the scholars claim that the proof of the need for deeper reform is that actions of many of the Central Banks have been unsuccessful. They may have succeeded in preventing the new economic collapse similar to 1930s, but, on the other side, the social cost of this was too great in the form of budget cuts, and significantly higher unemployment than before the crisis. These unemployment levels are still high today.

What they propose is the “outsider reform program”, which would focus on the following:

Governance of central banks and their independence

Changing the economic philosophy of central banks;

Big reform of the monetary policy, which would include adoption of an inflation target equal to the minimum unemployment rate of Inflation (MURI)

Other measures of the technical nature, such as asset-based reserve requirements;

Regulatory reform18.

I would like to briefly describe only points 2) and 3) because point 1) has been subject of numerous debates for many years in many countries, and there is probably no right or wrong answer that can be stamped on any given economy. Point 4) deals more with central banks’ regulatory and supervision role in the financial system, and point 5) has been going on in different countries at different speeds in different directions since the Financial Crisis started.

Changing the economic philosophy of the central banks.

Mr. Palley argues that the current thinking makes the central bankers favour only one range of outcomes of the monetary policy – they have a “preference for low inflation to protect financial wealth”19. Meanwhile, industrial capital will have a preference for a stronger real economy and lower unemployment. Workers of course will want full employment and higher real wages. Central bankers tend to side with the interests of financial capital, so the central banks will tend to favour macroeconomic outcomes, which have higher unemployment and lower inflation. This is a point lower on the Phillips curve. It is claimed that a central bank will more likely choose too low inflation, and if the economy has a negatively sloped Phillips curve, this causes permanent output losses and permanently higher unemployment20.

Mr. Palley says that this bias of the central banks in favour of the financial capital interests should be reversed, and that the central banks must fully represent competing interests so that a socially optimum inflation – unemployment outcome can be achieved.

Monetary Policy Reform

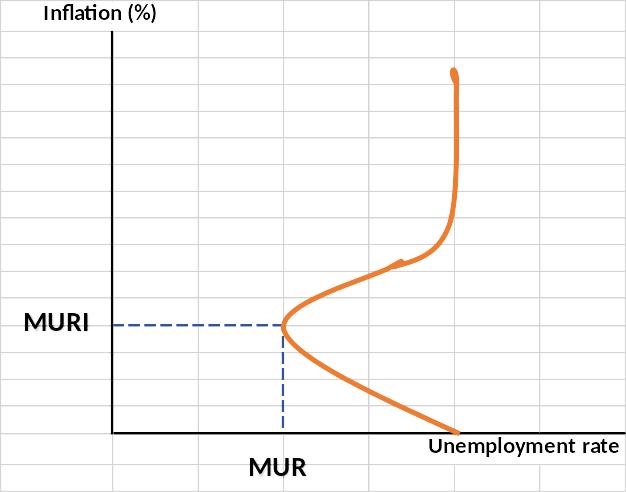

Mr. Palley’s proposition is rather radical – central banks should adopt such inflation targets that a point can be reached where the sustainable rate of unemployment is minimal. In his view, the Phillips curve, showing the trade-off between unemployment and inflation, is backward bending and central banks should redirect their policies 180º. That is, to make inflation rate a subsidiary indicator, and the unemployment rate – the primary target. He also proposes a term for this level of inflation – the minimum unemployment rate of inflation – or MURI. This is the opposite of NAIRU – non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment. The backward bending Phillips curve and the MURI are illustrated in the graph below21.

Palley gives the reason why the curve is backward bending. It is because workers in high unemployment industries may agree to a small real wage reduction (for example, by having the same nominal wage for another year or two) at low rates of inflation. However, at higher rates of inflation reduction in real wage is unacceptable, therefore the curve bends backwards.

In Palley’s opinion, at low rates inflation is not a concern, and instead the unemployment is the real concern. Therefore, it is important that inflation targeting should be formalized in such a way, that the central bank has a responsibility for real economic performance22.

My own view is that this is a very bold and radical proposition, which the central banks will not like. However, this debate is far from over and ongoing.