Функциональный стиль научной прозы

Задание 6. Ознакомьтесь со следующими текстами: а)“Joining by Brazing’, б)‘Patents and Inventions’, в) ‘Touchy-Feely Computing”, г)’Powerful Management Capabilities for a Variety of Networks’. Определите, к какой из разновидностей функционального стиля научной прозы они принадлежат. Укажите, какие характерные черты данного функционального стиля и особенности подстиля присутствуют в каждом тексте. При подготовке этого задания рекомендуется изучить материал части 2 данного пособия.

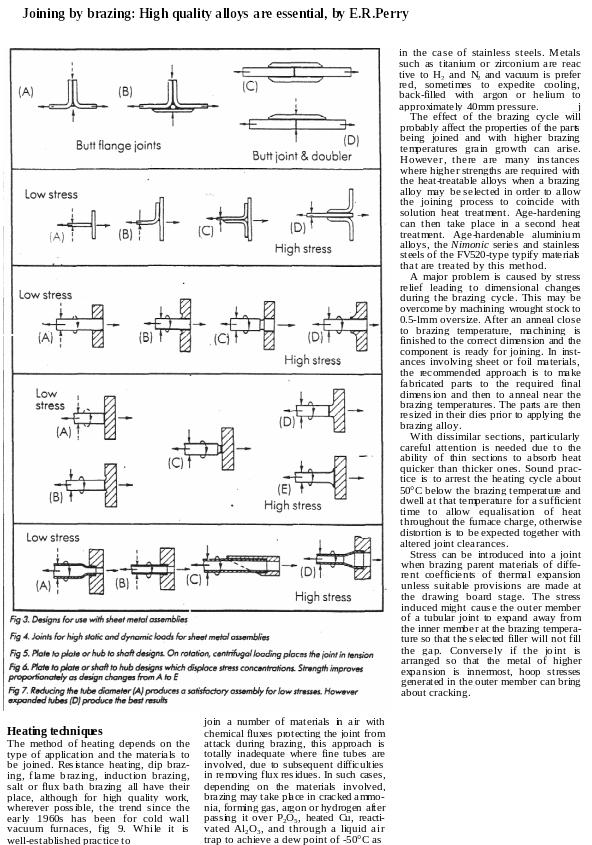

а) Отрывок текста “Joining by brazing” (E.R.Perry)

Heating techniques

The method of heating depends on the type of application and the materials to be joined. Resistance heating, dip brazing, flame brazing, induction brazing, salt or flux bath brazing all have their place, although for high quality work, wherever possible, the trend since the early 1960s has been for cold wall vacuum furnaces, fig 9.

While

it is well-established practice to

join

a number of materials in air with chemical

fluxes protecting the joint from attack

during brazing, this approach is totally inadequate where fine tubes

are involved,

due to subsequent difficulties in

removing flux residues. In such cases, depending

on the materials involved, brazing

may take place in cracked ammonia,

forming gas, argon or hydrogen after passing

it over P2O5,

heated Cu, reactivated

Al2O3,

and through a liquid air trap

to achieve a dew point of -50°C as

iJoining by brazing: High quality alloys are essential, by e.R.Perry

n the case of stainless steels. Metals such

as titanium or zirconium are reactive

to H2

and N2

and vacuum is preferred,

sometimes to expedite cooling, back-filled

with argon or helium to approximately

40mm pressure.

The effect of the brazing cycle will probably affect the properties of the parts being joined and with higher brazing temperatures grain growth can arise. However, there are many instances where higher strengths are required with the heat-treatable alloys when a brazing alloy may be selected in order to allow the joining process to coincide with solution heat treatment. Age-hardening can then take place in a second heat treatment. Age-hardenable aluminium alloys, the Nimonic series and stainless steels of the FV520-type typify materials that are treated by this method.

A major problem is caused by stress relief leading to dimensional changes during the brazing cycle. This may be overcome by machining wrought stock to 0.5-lmm oversize. After an anneal close to brazing temperature, machining is finished to the correct dimension and the component is ready for joining. In instances involving sheet or foil materials, the recommended approach is to make fabricated parts to the required final dimension and then to anneal near the brazing temperatures. The parts are then resized in their dies prior to applying the brazing alloy.

With dissimilar sections, particularly careful attention is needed due to the ability of thin sections to absorb heat quicker than thicker ones. Sound practice is to arrest the heating cycle about 50°C below the brazing temperature and dwell at that temperature for a sufficient time to allow equalisation of heat throughout the furnace charge, otherwise distortion is to be expected together with altered joint clearances.

Stress can be introduced into a joint when brazing parent materials of different coefficients of thermal expansion unless suitable provisions are made at the drawing board stage. The stress induced might cause the outer member of a tubular joint to expand away from the inner member at the brazing temperature so that the selected filler will not fill the gap. Conversely if the joint is arranged so that the metal of higher expansion is innermost, hoop stresses generated in the outer member can bring about cracking. (Welding and Metal Fabrication)

Б) patents and inventions

When an invention is made, the inventor has three possible courses of action open to him: first, he can give the invention to the world by publishing it; keep the idea secret; or patent it. Secrecy obviously evaporates once the invention is sold or used, and -there is always the risk that in the meantime another inventor, working quite independently, will make and patent the same discovery. A granted patent is the result of a bargain struck between an inventor and the state, whereby, in return for a limited period of monopoly (16 years in the UK), the inventor publishes full details of his invention to the public.

Once the monopoly period expires, all those details of the invention pass into the public domain. Only in the most exceptional circumstances is the life-span of a patent extended to alter this normal process of events. The longest extension ever granted was to Georges Valensi: his 1939 patent for colour TV receiver circuitry was extended until 1971, because for most of the patent's normal life there was no colour TV to receive and thus no hope of reward for the invention. But even short extensions are normally extremely rare.

Because a patent remains perpetually published after it has expired, the shelves of the library attached to the British Patent Office contain details of literally millions of ideas that are free for anyone to use and, if older than half a century, sometimes even re-patent. Indeed, patent experts often advise anyone wishing to avoid the high cost of conducting a search through live patents that the one sure way of avoiding infringement of any other inventor's rights is to plagiarize a dead patent. Likewise, because publication of an idea in any other form permanently invalidates future patents on that idea, it is traditionally safe to cull ideas from other areas of print. Much modern technological advance is based on these presumptions of legal security.

Anyone closely involved in patents and inventions soon learns that most ’new’ ideas are, in fact, as old as the hills. It is their reduction to commercial practice, either through necessity, dedication or the availability of new technology, that makes news and money. The basic patents for the manufacture of margarine and the theory of magnetic recording date back to 1869 and 1886 respectively. Many of the original ideas behind television stem from the late 19th and early 20th century, well before Baird aroused public interest. Every stereo gramophone sold today owes its existence to theory patented by Blumlein in 1931, and even the Volkswagen rear engine car was anticipated by a 1904 patent for a cart with the horse at the rear.

Such anticipations can have surprising significance. The German chemical giant, BASF, was recently refused a patent for the clever idea of pumping expanded plastics into a submerged ship and thereby floating it to the surface. The grounds of the refusal were that the German Examiner had once seen a Walt Disney cartoon in which Donald Duck had performed a similar trick on a sunken boat with table-tennis balls. If the BASF scheme proves successful in practice and enables valuable wrecks to be salvaged it is unlikely that Walt Disney will be credited as the inventor.

Leonardo da Vinci's original ideas for flight were inevitably unpatented; but, in 1842, the Englishmen, Stringfellow and Henson, were granted a patent containing details of an aircraft of which a heavier-than-air model was reputed to have flown 60 years before Wilbur and Orville Wright. Another Englishman, James Butler, patented a jet engine in 1867 — a full 70 years before Frank Whittle's famous British patent for jet propulsion.

Incidentally, Whittle's patent was allowed to lapse after only four years, through non-payment of renewal fees, and passed into the public domain as early as January, 1934; but, by then, the inventor had signed an agreement with the Air Ministry.

Even the apparently safe history of the telephone and gramophone contains some surprises. US legal case law details how an American called Drawbaugh had ideas for a telephone which anticipated Bell's patents of 1875-76 by five years; but it was Alexander Graham Bell who made the system practical on a commercial level and was acknowledged and rewarded as inventor.

The future will produce many similar situations. Patents are daily being granted for ideas from inventors for schemes that cannot yet work — but that one day, following massive investment by industry, will become a reality. It is remarkably easy to sit in the comfort of an armchair and patent pipe-dreams which are nothing more than prophecies of the future and problems for others to solve.