- •Материалы для студентов из учебно-методического комплекса по дисциплине

- •Специальность: лечебное дело – 040100

- •Смоленск 2008

- •Цели и задачи дисциплины

- •Требования к уровню освоения содержания дисциплины

- •Перечень дисциплин,

- •Тематическое содержание преподаваемого раздела хирургии

- •Раздел 1. Абдоминальная хирургическая патология

- •Тема 1. Абдоминальный болевой синдром

- •Тема 2. Острый аппендицит

- •Тема 3. Вентральные грыжи и их осложнения

- •Тема 4. Осложненный холецистит, вопросы хирургии желчных путей

- •Тема 5. Острый панкреатит

- •Тема 6. Хронический панкреатит, кисты поджелудочной железы

- •Тема 7. Рак и гормональноактивные опухоли поджелудочной железы

- •Тема 8. Механическая желтуха, холангит

- •Тема 9. Осложнения язв желудка и двенадцатиперстной кишки

- •Тема 10. Болезни оперированного желудка

- •Тема 11. Гастроэзофагеальная рефлюксная болезнь

- •Тема 12. Кишечная непроходимость

- •Тема 13. Хроническая дуоденальная непроходимость

- •Тема 14. Кишечные свищи

- •Тема 15. Перитонит

- •Тема 16. Объемные заболевания печени

- •Тема 17. Хирургия селезенки

- •Тема 18. Забрюшинные опухоли

- •Тема 19. Заболевания диафрагмы.

- •Тема 20. Современные технологии в диагностике и лечении хирургических заболеваний.

- •Тема 21. Осложненный рак желудка.

- •Раздел 2. Кровотечения

- •Тема 22. Гастродуоденальные кровотечения

- •Тема 23. Легочные кровотечения

- •Раздел 3. Хирургия повреждений мирного времени

- •Тема 24. Травма живота мирного времени, торакоабдоминальные ранения мирного времени

- •Тема 25. Хирургия повреждений груди

- •Раздел 4. Ургентная сосудистая хирургическая патология

- •Тема 26. Тэла у хирургических больных и её профилактика.

- •Тема 27. Острые артериальные тромбозы и эмболии.

- •Тема 28. Тромбоз и эмболия мезентериальных сосудов

- •Тема 29. Воспалительные заболевания вен нижних конечностей

- •Тема 30. Гангрена на фоне облитерирующих заболеваний артерий нижних конечностей

- •Тема 31. Портальная гипертензия

- •Тема 38. Предраковые заболевания толстой кишки

- •Тема 39. Рак толстой кишки

- •Раздел 6. Гнойно-воспалительные заболевания

- •Тема 40. Раны и раневая инфекция

- •Раздел 7. Костно-суставная хирургическая патология

- •Тема 51. Остеомиелит

- •Темы и план лекций для студентов

- •Осложненный аппендицит. Клинические «маски» острого аппендицита.

- •Заболевания, имитирующие «острый живот». Хирургические осложнения инфекционных и паразитарных заболеваний.

- •Ущемленные грыжи. Диагностика. Ошибки, опасности, особенности и осложнения в хирургическом лечении грыж.

- •Перитонит. Классификация, патогенез эндотоксикоза, клиника Лечение перитонита, перитонеальный лаваж, программированная релапаротомия, лапаростомия.

- •Осложненный холецистит.

- •Механическая желтуха.

- •Современная диагностика и дифференцированное лечение желудочно-кишечных кровотечений.

- •Повреждения груди мирного времени.

- •Повреждения живота мирного времени.

- •Осложненный рак желудка.

- •Осложненный рак прямой кишки.

- •Осложненный рак ободочной кишки.

- •Геморрой и его осложнения. Современные методы лечения.

- •Частные вопросы неотложной колопроктологии.

- •Легочные кровотечения.

- •Послеоперационные тромбоэмболические осложнения. Профилактика и лечение.

- •Ишемическая болезнь органов пищеварения. Острые нарушения мезентериального кровообращения.

- •Хирургический сепсис, классификация, клиника. Лечение сепсиса и хирургического инфекционно-воспалительного эндотоксикоза.

- •Эндовидеохирургические технологии (прошлое, настоящее, будущее).

- •Дифференцированные подходы к лечению хронического панкреатита.

- •Современные методы лечения кишечных свищей.

- •Болезни оперированного желудка. Показания к хирургическим методам лечения.

- •Гастроэзофагеальная рефлюксная болезнь, показания к хирургическому лечению.

- •Синдром диабетической стопы.

- •Зоб. Клиника, дифференциальная диагностика, хирургическое лечение.

- •Рак поджелудочной железы.

- •Опухоли печени.

- •Забрюшинные опухоли.

- •Хроническая дуоденальная непроходимость.

- •Заболевания диафрагмы.

- •Хирургия селезенки.

- •Иммунная система человека при гнойно-воспалительных и опухолевых онкологических заболеваниях органов брюшной полости.

- •Факультативные лекции

- •История кафедры и клиники госпитальной хирургии.

- •Достижения трансплантологии.

- •Портальная гипертензия.

- •Элективный курс практических занятий

- •Тема 1.Экстренная видеолапароскопия

- •Тема 2. Видеолапароскопия в плановой хирургии

- •Тема 3. Основные принципы и тактика озонотерапии в хирургии

- •Тема 4. Применение в хирургической практике гипохлорита натрия, получаемого электрохимическим методом

- •Учебно-методическое обеспечение дисциплины

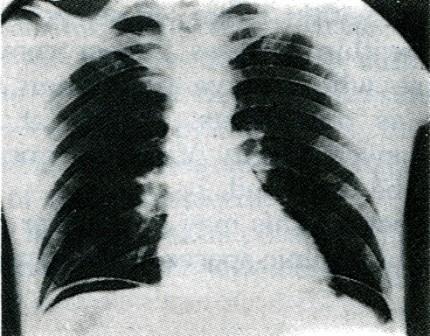

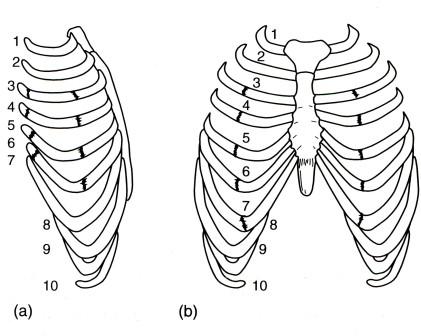

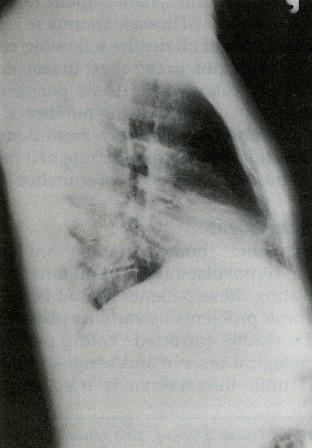

- •Виды экзаменационных рентгенограмм

- •Задача 2.

- •Задача 3.

- •Задача 4.

- •Задача 5.

- •Задача 6.

- •Задача 7.

- •Задача 8.

- •Задача 9.

- •Задача 10.

- •Задача 11.

- •Задача 12.

- •Задача 13.

- •Задача 14.

- •Задача № 15

- •Задача 16.

- •Задача 17.

- •Задача 18.

- •Задача 19.

- •Задача 20.

- •Задача 21.

- •Задача 22.

- •Задача 23.

- •Задача 24.

- •Задача 25.

- •Задача 26.

- •Задача 27.

- •Задача 28.

- •Задача 29.

- •Задача 30. Больной, 50 лет, предъявляет жалобы на слабость, головокружение, окрашивание кала в черный цвет.

- •Задача 31.

- •Вопросы:

- •Ответы:

- •Задача 32.

- •Вопросы:

- •Задача 33.

- •Ответы:

- •Задача 34.

- •Задача 35.

- •Задача 36.

- •Задача 37.

- •Вопросы:

- •Задача 38.

- •Задача 39.

- •Задача 40.

- •Задача 41.

- •Задача 42.

- •Задача 43.

- •Задача 44.

- •Задача 45.

- •Задача 46.

- •Задача 47.

- •Задача 48.

- •Задача 49.

- •Задача 50.

- •Задача 51.

- •Задача 52.

- •Задача 53.

- •Задача 54.

- •Задача 55.

- •Задача 56.

- •Задача 57.

- •Задача 58.

- •Задача 59.

- •Задача 60.

- •Задача 61.

- •Задача 62.

- •Задача 63.

- •Задача 64.

- •Задача 65.

- •Задача 66.

- •Задача 67.

- •Задача 68.

- •Задача 69.

- •Задача 70.

- •Задача 71.

- •Задача 72.

- •Задача 73.

- •Задача 74.

- •Задача 75.

- •Задача 76.

- •Задача 77.

- •Острый аппендицит (варианты течения, осложнения)

- •2. Основные понятия

- •Классификация (по Колесову)

- •3. Вопросы к занятию.

- •4. Вопросы для самоконтроля.

- •5. Рекомендуемая литература.

- •Грыжи брюшной стенки, внутренние грыжи. Ущемленные грыжи (дифференциальный диагноз, клиника и особенности хирургической тактики)

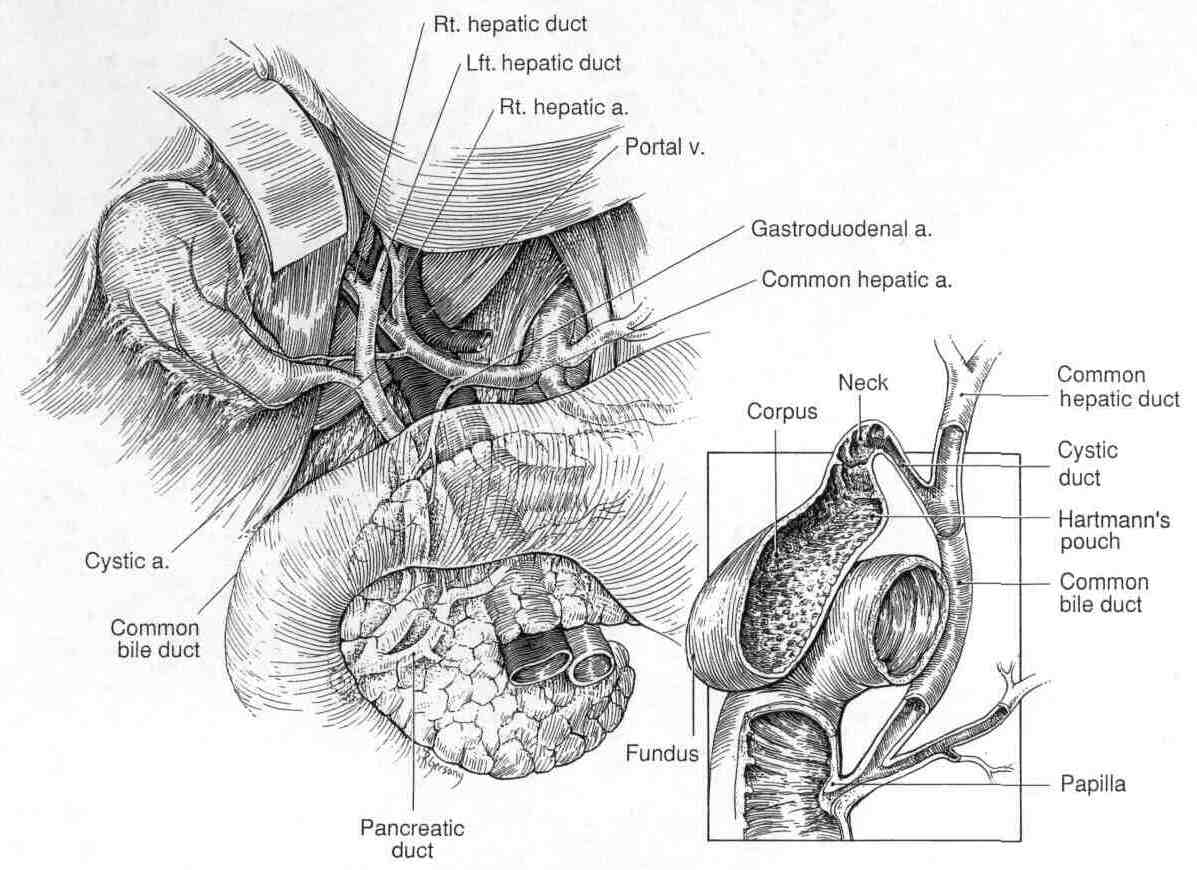

- •Острый холецистит (клиника, осложнения, методы исследования желчевыводящих путей, оперативное и консервативное лечение, показания холедохотомии, методы дренирования холедоха)

- •1. Цель изучения.

- •2. Основные понятия

- •3. Вопросы к занятию.

- •1Особенности течения у беременных и пожилых людей

- •4. Вопросы для самоконтроля.

- •5. Литература

- •Острый панкреатит (классификация, стадии воспалительного процесса, консервативное лечение, показания и варианты хирургического пособия)

- •4. Основные понятия

- •5. Вопросы к занятию

- •6. Вопросы для самоконтроля

- •7. Основная и дополнительная литература

- •Хронический панкреатит, кисты и рак поджелудочной железы

- •4. Основные понятия:

- •5. Вопросы к занятию

- •6. Вопросы для самоконтроля

- •7. Основная и дополнительная литература

- •Механическая желтуха, холангит (классификация, дифференциальная диагностика, хирургическая тактика). Дренирующие и реконструктивные операции на желчевыводящих путях

- •4. Основные понятия

- •5. Вопросы к занятию

- •7. Основная и дополнительная литература

- •Диагностика и хирургическая тактика при осложнениях язв желудка и двенадцатиперстной кишки (прободение, пилородуоденальный стеноз, малигнизация, пенетрация)

- •Гастродуоденальные кровотечения (классификация, диагностика, хирургическая тактика)

- •Тема занятия, его цели и задачи.

- •2. Основные понятия:

- •3. Вопросы к занятию:

- •4.Вопросы для самоконтроля

- •Повреждения живота мирного времени. Торакоабдоминальные ранения (тупая травма, проникающие ранения, изолированные и сочетанные повреждения внутренних органов)

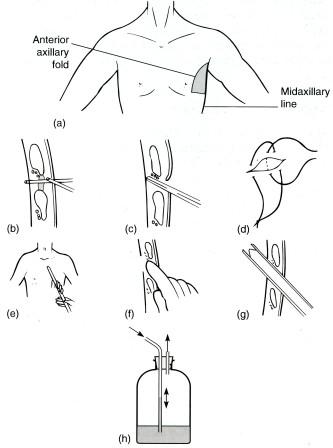

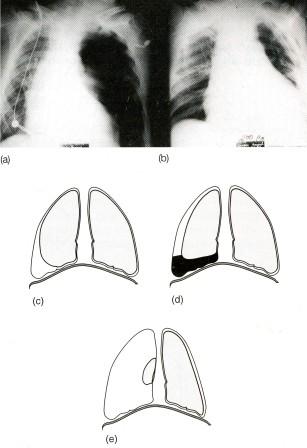

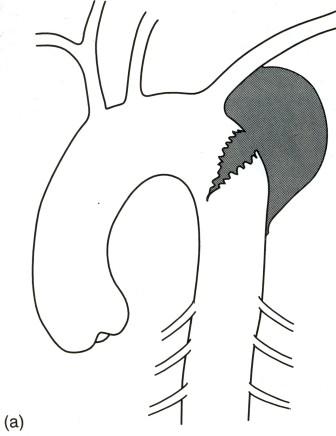

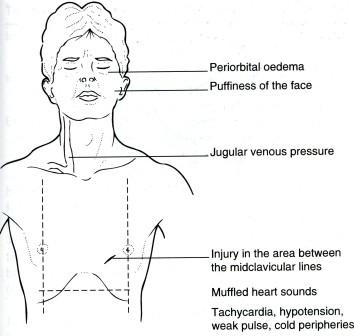

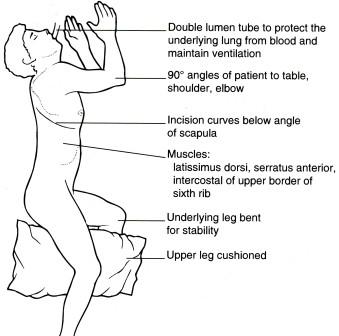

- •Хирургия повреждений груди мирного времени.

- •Острые артериальные тромбозы и эмболии. Флеботромбоз. Тэла у хирургических больных и её профилактика

- •Эндовидеохирургические технологии в диагностике и лечении ургентной абдоминальной патологии

- •2. Основные понятия

- •3. Вопросы к занятию.

- •4. Вопросы для самоконтроля.

- •2Кровоснабжение органов брюшной полости.

- •5. Литература

- •Вопросы для самоконтроля.

- •Дифференцированное лечение кишечной непроходимости. Методы кишечной декомпрессии, энтеральный лаваж

- •Перитонит (классификация, клиника, хирургическая тактика). Показания и методы перитонеального лаважа. Показания к программированной релапаротомии. Лапаростомия

- •Методические указания для студентов 6 курса

- •4. Основные понятия

- •5. Вопросы к занятию

- •6. Вопросы для самоконтроля

- •7. Основная и дополнительная литература

- •Раны и раневая инфекция. Современные подходы в лечении трофических язв, пролежней. Профилактика их развития

- •Назовите наиболее часто встречающихся возбудителей гнойной инфекции;

- •Хирургические заболевания и сахарный диабет. Синдром диабетической стопы

- •Золоев г.К. Облитерирующие заболевания артерий. – м., 2004. – 432с.

- •Хирургический сепсис. Синдром системного воспалительного ответа на инфекцию. Токсико-септический шок

- •Хроническая венозная недостаточность. Тромбофлебит (классификация, клиника, диагностика, лечение). Трофические язвы венозной этиологии

- •Гангрена конечностей на фоне облитерирующих заболеваний артерий нижних конечностей (клиника, диагностика, лечение)

- •Дифференциальная диагностика и лечение гнойно-воспалительных заболеваний кожи и подкожной клетчатки: фурункул и фурункулез, карбункул, абсцесс, флегмона, рожа, эризипелоид

- •Дифференциальная диагностика и лечение гнойно-воспалительных заболеваний: гидраденит, лимфангит и лимфаденит, мастит

- •Панариций. Остеомиелит

- •Флегмоны кисти и стопы. Флегмона пространства пирогова-парона

- •4. Основные понятия

- •5. Вопросы к занятию

- •Основная:

- •Артрозы, артриты, бурситы, гигромы. Остеохондропатии: болезнь Осгуд-Шлаттера, Шейермана-Мау, Пертеса, Кинбека, Келлера I и Келлера II (этиология, клиника, диагностика, лечение)

- •4. Основные понятия

- •5. Вопросы к занятию

- •Основная:

- •Тема: колоректальный рак Цели изучения

- •1. Предопухолевая патология толс-той кишки.

- •2. Клинические классификации для опухолей ободочной и прямой кишок.

- •3. Метастазирование колоректаль-ного рака.

- •4. Клинические проявления.

- •Диагностические исследования.

- •6.Скрининг колоректального рака.

- •8. Реабилитация.

- •9.Отдаленные результаты.

- •Вариант 2.

- •Вариант 3.

- •Вариант 4.

- •На тестовый контроль исходного уровня знаний

- •1 Вариант

- •На тестовый контроль исходного уровня знаний

- •2 Вариант

- •На тестовый контроль исходного уровня знаний

- •3 Вариант

- •На тестовый контроль исходного уровня знаний

- •4 Вариант

- •Тестовые задания для входного контроля (факультет иностранных студентов)

- •Программированный контроль к зачетному занятию по циклу

- •Программированный контроль к зачетному занятию по циклу

- •Программированный контроль к зачетному занятию по циклу

- •Программированный контроль к зачетному занятию по циклу

- •Программированный контроль к зачетному занятию по циклу

- •Программированный контроль к зачетному занятию по циклу

- •Итоговый тестовый контроль на кафедре госпитальной хирургии Вариант 1

- •Вариант 2

- •Вариант 3

- •5. Наличие яичка в грыжевом мешке характерно для грыжи:

- •Вариант 4

- •78. Для фазы дегидратации в течении раневого процесса характерно:

- •Тестовые задания для итогового контроля (факультет иностранных студентов)

- •Учебно-клинической истории болезни

- •1. Расспрос больного.

- •1. Осмотр.

- •2. Пальпация.

- •3. Перкуссия.

- •6. Определение характера пульса.

- •7. Измерение артериального давления.

- •8. Измерение венозного давления.

- •Дигитальный метод дополнительного исследования

- •Пальцевое исследование прямой кишки.

- •Инструментальные манипуляции

- •1. Исследование прямой кишки с помощью ректального зеркала.

- •4. Венесекция.

- •5. Пункция плевральной полости.

- •6. Пункция полости перикарда.

- •7. Пункция брюшной полости (лапароцентез).

- •8. Пункция коленного сустава.

- •9. Блокады анестетиками.

- •Словарь терминов и персоналий (глоссарий)

- •Русско-латинский словарь необходимых медицинских терминов

Артрозы, артриты, бурситы, гигромы. Остеохондропатии: болезнь Осгуд-Шлаттера, Шейермана-Мау, Пертеса, Кинбека, Келлера I и Келлера II (этиология, клиника, диагностика, лечение)

Составитель ассистент О.Г.Шахбазян

Методические указания утверждены на методическом совещании кафедры госпитальной хирургии (протокол № 2 от 6 октября 2008 г.)

Зав. кафедрой______________(проф. С.А.Касумьян)

2008 г.

1. Тема занятия: Артрозы, артриты, бурситы, гигромы (классификация, клиника, диагностика, лечение). Остеохондропатии: болезнь Осгут-Шлаттера, Шейермана-Мау, Пертеса, Кинбека, Келлера I и Келлера II (этиология, клиника, диагностика, лечение).

2.Цель занятия: Изучение методов диагностики артрозов, артритов, бурситов и гигром. Изучение методов диагностики остеохондропатий. Определение показаний к оперативному лечению.

3.Задачи: Определение тактики в отношении конкретного больного в зависимости от тяжести заболевания, изучение методов консервативного лечения, профилактики осложнений, определение показаний к оперативному лечению, знание основных методов операций.

4. Основные понятия

Артроз.

Артрит.

Бурсит.

Гигромы.

Болезнь Осгут-Шлаттера.

Болезнь Шейермана-Мау.

Болезнь Пертеса.

Болезнь Кинбека.

Болезнь Келлера I.

Болезнь Келлера II.

5. Вопросы к занятию

Этиология артрозов.

Этиология и классификация артритов и бурситов.

Клиника, диагностика артрозов, артритов, бурситов и гигром.

Этиология, патогенез, клиника, диагностика остеохондропатий.

Методы диагностики заболеваний опорно-двигательной системы.

Методы консервативного и оперативного лечения артрозов, артритов, бурситов и гигром.

Особенность хирургической обработки гнойного очага.

Методы лечения при остеохондропатиях.

Основные осложнения и их профилактика.

Рекомендуемая литература.

Основная:

Исаков Ю.Ф. Хирургические болезни детского возраста: Учебник для студентов медицинских вузов (в 2-х томах). – 2006.

Клиническая хирургия: в 3 т. Национальное руководство / Под ред. В.С.Савельева, А.И.Кириенко. – 2008. (+CD)

Николаев А.В. Топографическая анатомия и оперативная хирургия. Учебник для студентов медицинских вузов. – 2007. – 784с.

Травматология. Национальное руководство / Под ред. Г.П.Котельникова, С.П.Миронова. – 2008. – 808с. (+CD)

Дополнительная:

Амбулаторная хирургия. Справочник практического врача /Под ред. проф. В.В.Гриценко, проф. Ю.Д.Игнатова. – СПб.: Издательский Дом «Нева»; М.: «Олма-Пресс Звездный мир», 2002. – 448с.

Пауткин Ю.Ф. Поликлиническая хирургия. – М.: Высшая школа, 2005. – 287с.

Методическая разработка кафедры по теме практического занятия.

МЕТОДИЧЕСКИЕ УКАЗАНИЯ ДЛЯ СТУДЕНТОВ

По дисциплине хирургические болезни

Для специальности лечебное дело – 040100

Кафедра госпитальной хирургии

Курс 6 курс

Семестр XI-XII

Факультет иностранных студентов

ГОУ ВПО «Смоленская государственная медицинская академия

Федерального агентства по здравоохранению и социальному развитию»

МЕТОДИЧЕСКИЕ УКАЗАНИЯ ДЛЯ СТУДЕНТОВ

ПО ДИСЦИПЛИНЕ хирургические болезни

ACUTE APPENDICITIS

(variants of its clinical features, complications)

Составитель доц. А.Ю.Некрасов

Методические указания утверждены на методическом совещании кафедры госпитальной хирургии (протокол № 2 от 6 октября 2008 г.)

Зав. кафедрой______________(проф. С.А.Касумьян)

2008 г.

QUESTIONS FOR HOMEWORK:

1. Anatomy

2. Classification

3. Pathophy

4. Clinical symptoms.

5. Diagnostics.

6. Differential diagnosis.

7. Complications of appendicitis.

8. Appendicitis during pregnancy.

9. Chronic or recurrent appendicitis.

10. Treatment.

11. Postoperative complications.

ANATOMY

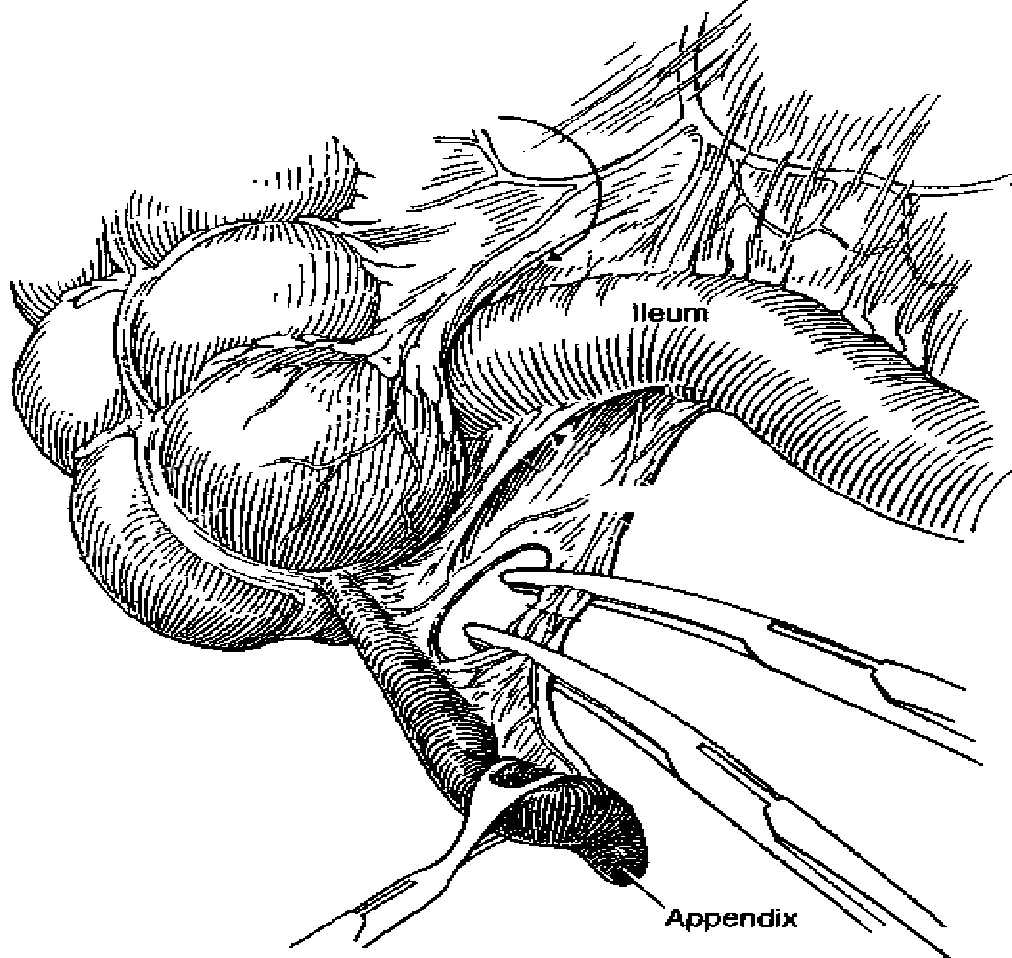

Although the base of the appendix is consistently found of the cecum, can be located in a variety of locations. The most common location of the appendix is retrocecal but within the peritoneal cavity, because the most inferior portion of the cecum is within the peritoneal cavity. This situation occurs approximately 65% of the time. It is pelvic in location in 30% and retroperitoneal in 2% of the population. The tip of the appendix can also be found in a preileal or postileal location. The varying location of the appendix explains the myriad of symptoms that can be found in patients with appendicitis.

The appendicle artery, a branch of the ileocolic artery, supplies the appendix. Histological examination of the appendix shows a number of lymphoid follicles in the submucosa. The lumen of the appendix is often obliterated in elderly persons. The appendix in the adult can vary widely in length from 2 to 11 cm but averages about 9 cm in length.

CLASSIFICATION OF ACUTE APPENDICITIS (B.V. PETROVSKIY, 1980)

Appendicolitis (functional form).

Simple or catarrhal appendicitis.

Destructive appendicitis: phlegmone; gangrenous appendix, perforated and nonperforated.

Complication of appendicitis: periappendiceal infiltration; periappendiceal abscess; peritonitis; phlegmone of the mesenteric; sepsis; other complications.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Appendicitis is caused by obstruction of the appendiceal lumen from a variety of causes. Independent of the etiology, obstruction is believed to cause an increase in pressure within the lumen. Such an increase is related to continuous secretion of fluids and mucus from the mucosa and the stagnation of this material. At the same time, intestinal bacteria within the appendix multiply, leading to the recruitment of white blood cells, pus formation and subsequent increase of intraluminal pressure.

If appendiceal obstruction persists, intraluminal pressure rises ultimately above that of the appendiceal veins, leading to venous outflow obstruction. As a consequence, appendiceal wall ischemia begins. It may resulting in a loss of epithelial integrity and allow bacterial invasion of the appendiceal wall.

Within a few hours, this localized condition may worsen because of thrombosis of the appendicular artery and veins. The mair veason of it’s thrombosis of veins and arteries that supply the appendix. This phenomenon leads to perforation and gangrene of the appendix.

CLINICAL SYMPTOMS

The typical history is one of an onset of generalized abdominal pain followed by anorexia and nausea. The pain then becomes most prominent in the epigastrium and gradually moves toward the umbilicus, finally localizing in the right lower quadrant (Cocher,s symptom).

Examination of the abdomen usually shows:

Diminished bowel sounds, with direct tenderness and muscle spasm in the right lower quadrant. As the process continues the amount of spasm increases, with the appearance of rebound tenderness.

The temperature is usually mildly elevated (approximately 38°C) and usually rises to higher levels in the event of perforation, although this is very variable.

Tenderness on palpation in the right lower quadrant is the most important sign in these patients.

Additional signs such as increasing pain with cough (ie, Dunphy sign)

Rebound tenderness related to peritoneal irritation elicited by deep palpation with quick release (ie, Blumberg sign), and guarding may or may not be present. Right lower quadrant pain might be increased when patient turns on the right side.

Rovsing sign, which is elicited when pressure applied in the left lower quadrant reflects pain in the right lower quadrant, often is present but not specific.

The psoas sign (Bartomye-Michelson sign) may be positive and is elicited by extension of the right thigh with the patient lying on the left side. As the examiner extends the right thigh with stretching of the muscle, pain suggests the presence of an inflamed appendix overlying the psoas muscle.

The obturator sign (Coup sing) can be elicited with the patient in the supine position with passive rotation of the flexed right hip. Pain with this maneuver indicates a positive sign.

Obrazcov sign –increasing pain elicited when the pressure applied in the right lower quadrant during the lifting and straightening of the right foot.

Rectal examination should be performed in any patient with an unclear clinical picture, and a pelvic examination should be performed in all women with abdominal pain.

If the appendix ruptures, abdominal pain becomes intense and more diffuse, the muscular spasm increases, and there is a simultaneous increase in the heart rate, with a rise in temperature to 39° to 40°C. Rarely, there may be a slight diminishing of pain with rupture, presumably due to the decreased distention of the appendix, but a true pain-free interval would be quite uncommon.

FURTHER WORKUP

Laboratory. The majority of patients with acute abdominal pain have a complete blood count as a component of the evaluation. The leukocyte count is usually elevated to the range of 12,000 to 18,000. In addition, an increase in the percentage of younger neutrophil forms (the "left shift") with a normal total white blood cell count supports the clinical diagnosis of appendicitis. A completely normal leukocyte count differential is uncommon in patients with appendicitis. Other laboratory indices of inflammation have been studied as adjuncts to diagnosis of appendicitis.

A urinalysis is often obtained in the evaluation of patients with abdominal pain to determine whether genitourinary tract inflammation is present. The urinalysis may show a mild pyuria with appendicitis owing to the proximity of the ureter to the inflamed appendix. The increased specific gravity of the urine adds to the clinical diagnosis of hypovolemia. Proteinuria can also be an adjunct to the diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis as a complication of nephrotic syndrome in children evaluated for acute abdominal pain.

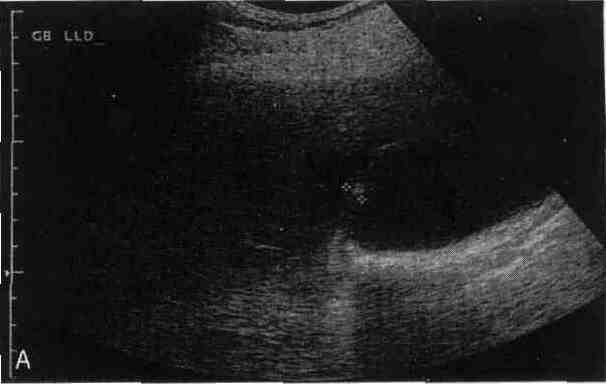

Ultrasound. Ultrasound (US) is noninvasive and rapidly available and avoids radiation exposure. However, the sonogram for appendicitis is a highly operator-dependent study. A healthy appendix usually cannot be viewed with US. When appendicitis occurs, the US typically demonstrates a noncompressible tubular structure of 7-9 mm in diameter. Interruption of the continuity of the echogenic submucosa, appendicolith and periappendiceal fluid or mass might be observed.

Abdominal radiographs. This study may be useful in patients with atypical presenting symptoms and physical signs. Abdominal radiographs may demonstrate a fecalith, localized ileus, or loss of the peritoneal fat stripe.

Computed tomography. Typically, CT has been reserved for patients with an equivocal history and physical and laboratory findings. CT is useful in patients with an observed inflammatory abdominal process, and the presentation is atypical for appendicitis.

Nuclear medicine. There is a renewed interest in the use of nuclear medicine studies to evaluate patients with suspected appendicitis. The true potential usefulness of these studies occurs in patients with persistent symptoms and negative US and CT studies.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

There are some common diagnoses to consider in the differential of appendicitis including:

Diseases of abdominal cavity organs: acute cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis, gastric and duodenum ulcers, intussusception, Crohn's disease, Meckel's diverticulitis and others;

Urologic diseases: renal colic, nephrolithiasis, paranephritis, acute pyelonephritis, and urinary tract infection;

Gynecological diseases: ovarian cyst or torsion, ectopic pregnancy, ovarian tumor, endometritis, acute adnexitis;

Infectious diseases: acute gastroenteritis, perityphlitis, enterokolitis digestive disorder;

Thoracic diseases: pneumonia, pleurisy, myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease;

The large majority of patients can be diagnosed and treated on the basis of a good history, physical examination, and judicious use of laboratory tests.

COMPLICATIONS OF APPENDICITIS

Periappendiceal infiltration – the inflammatory conglomeration, which consist of appendix and prepossessing near organs and tissues. It may be friable and compact.

Periappendiceal abscess – it is formed after the suppuration of infiltration. The leukocyte count and ESR usually elevated, the "left shift" is found. The temperature is usually raised to higher levels.

There also has been a bias toward early removal of the perforated appendix/appendiceal abscess to "control intra-abdominal sepsis." The preferred approach to the management of the appendiceal mass is percutaneous drainage, which is performed under image guidance (ultrasound or CT) and intravenous antibiotics directed against aerobic gram-negative and anaerobic organisms, followed by interval appaendectomy. Numerous studies have documented the safety and efficacy of this approach.

In late, complicated appendicitis, appendectomy can be a hazardous procedure. Surgery at this stage can serve to disseminate a localized inflammatory process; to injure surrounding inflamed or edematous bowel, resulting in fistulas; or to require more extensive procedures, such as cecectomy or right hemicolectomy. Historically, this has been fueled by equivocal imaging studies that could not reliably corroborate the physical findings and an inability to reliably drain an abscess percutaneously.

Perforated appendicitis. Patients with perforated appendicitis will often have a longer duration of symptoms, high fever, and a higher white blood cells count. Most of these patients are volume depleted and require several hours or more of fluid resuscitation before operative intervention. It is important to ensure that the patient has been adequately resuscitated before undertaking an operation. Patients with perforated disease have established peritonitis and should receive appropriate broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic therapy, which should start as soon as the diagnosis is established. The duration of therapy is controversial. Some authors recommend an empiric time of treatment such as 7 or 10 days. Others suggest treatment until the patient is afebrile with a normal white blood cell count.

As with acute appendicitis, there are two possible approaches: an open laparotomy or laparoscopy. There is some controversy about the use of laparoscopy in patients with advanced disease because the incidence of postoperative intra-abdominal abscess formation in some series has been markedly higher with laparoscopy than with an open approach.

APPENDICITIS DURING PREGNANCY

Appendicitis and cholecystitis are the most frequent causes of abdominal pain during pregnancy. Abdominal tenderness is the most important finding in appendicitis, but the location of point tenderness varies during gestation. After the fifth month of gestation, the appendiceal position is shifted superiorly above the iliac crest, and the appendix tip is rotated medially by the gravid uterus.

The whole blood cell count may not be helpful because it is frequently elevated during pregnancy. Common symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, anorexia are also common during pregnancy and thus of limited diagnostic value. Ultrasound may be of help if a thickened or dilated appendix is identified.

Suspicion of appendicitis should lead to early surgical intervention in all trimesters. Negative laparotomy results in minimal fetal loss, whereas a delay in diagnosis and perforation may result in a high incidence of fetal death and a relatively high incidence of maternal death. A laparoscopic approach has been used and does not appear to increase maternal or fetal morbidity or mortality rates.

CHRONIC OR RECURRENT APPENDICITIS

The occurrence of chronic or recurrent appendicitis is controversial, and although rare, its existence may be plausible. Intermittent bouts of obstruction of the appendiceal lumen with spontaneous remission may be the cause. Mild local inflammation after a resolving attack of acute appendicitis may result in chronic right lower quadrant discomfort.

The appearance of the appendix on CT in patients with recurrent or chronic appendicitis reportedly demonstrates findings similar to acute appendicitis. Patients undergoing appendectomy for chronic lower abdominal pain frequently demonstrate abnormal histology of the appendix and are relieved of their symptoms.

TREATMENT

The treatment of appendicitis depends on the stage of the disease. In general, patients should receive fluid resuscitation before surgery, but this may require only 1 or 2 hours in patients with nonperforated disease. There is a general consensus that prophylactic antibiotics should be administered before the start of the operation, a single dose of cefoxitin or cefotaxime is administered.

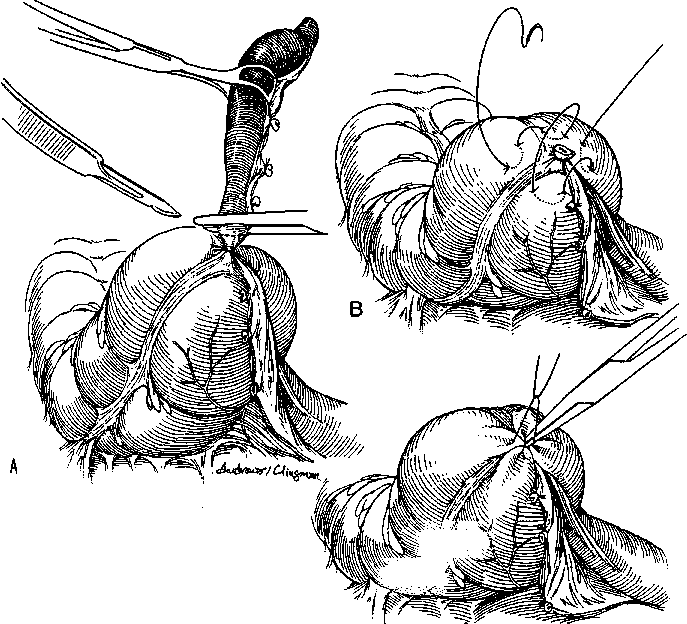

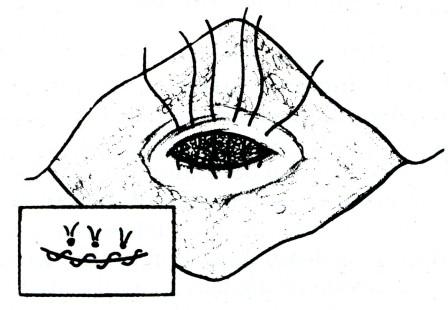

There are two approaches to removal of the nonperforated appendix: through an open incision, usually a transverse right lower quadrant skin incision (Davis-Rockey) or an oblique version (McArthur-McBurney) with separation of the muscles in the direction of their fibers, or a paramedian incision, but this is not routinely done. The incision is centered on the medioclavicular line (Fig.1). Once the peritoneum is entered, the appendix is delivered into the field. This can usually be accomplished with careful digital manipulation of the appendix and cecum. In difficult cases, extending the incision 1 to 2 cm can greatly simplify the procedure. Once the appendix is delivered into the wound, the mesoappendix is sacrificed between clamps and ties (Fig.2). There are several ways to handle the actual removal of the appendix. Some surgeons simply suture ligate the base of the appendix and excise it. Others place a pursestring or Z – stitch in the cecum, excise the appendix, and invert the stump into the cecum (Fig.3). Once the appendix is removed, the cecum is returned to the abdomen, and the peritoneum is closed.

The appendix can also be removed laparoscopically. Although there is not universal agreement, the body of information suggests that in the adult, although operative costs are higher due to a longer procedure and more equipment needed with laparoscopy, the overall costs are lower because the pain is less and patients can return to work sooner.

In a laparoscopic procedure appendix is grasped by atraumatic grasper and retracted upward to expose the mesoappendix. The mesoappendix is divided using a dissector then ligated with a linear Endostapler, Endoclip, or suture ligature. The mesoappendix is transected using a scissor or electrocautery. To avoid perforation of the appendix and iatrogenic peritonitis, the tip of the appendix should not be grasped. The appendix may now be transected with a linear Endostapler, or, alternately, the base of the appendix may be suture ligated in a similar manner to that in an open procedure. The appendiceal stump is not buried, and the the appendix is removed through one of the port sites. Peritoneal irrigation is performed with antibiotic or saline solution. The fascial layers are closed with absorbable suture, while the cutaneous incisions are closed with interrupted subcuticular sutures or sterile adhesive strips.

Figure 1. Location for the common incisions used for an appendectomy.

Figure 2.Division of the mesoappendix during an open appendectomy

Figure 3. Steps in an open appendectomy. A. The appendix is divided after ligation. B. A Z or pursestring stitch is placed in the cecum. C. Inversion of the appendiceal stamp

POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

Infection. Infection remains the most common complication after the operative treatment of appendicitis. Although infection can occur in a number of locations, surgical site infection predominates. The two sites at which infections can occur are the subcutaneous wound and within the abdominal cavity.

The incidence of wound infection and intra-abdominal sepsis in patients with complicated appendicitis is higher than that in patients with nonperforated appendicitis. There have been several reports of a much higher incidence of abscess formation in patients with complicated appendicitis who have undergone laparoscopic appendectomy. The mechanism is unclear at this time.

Bowel obstruction. Intestinal obstruction can occur after laparotomy for appendicitis. The true long-term incidence is unknown, but it is likely similar to the risk of patients undergoing laparotomy for other reasons.

Infertility. The risk of tubal infertility in female patients after appendicitis is unclear. In one large study, there was no increased risk of infertility in patients with nonperforated appendicitis but a several-fold increase in infertility in patients with perforated appendicitis. However, another study showed no difference in either group. Regardless, the risk appears to be sufficiently low that patients do not require routine evaluations unless there is a proven problem with fertility.

Miscellaneous. As with any operation, a number of other problems may occur. Complications which can occur in patients with appendicitis:

urinary tract infections’

pneumonia

a fecae fistula

TESTS

1 . The Earliest symptoms of acute appendicitis is

a) Pain

b) Fever

c) Vomiting

d) Rise of pulse rate

2. The Commonest position of the appendix -

a) Retrocaecal

b) Preileal

c) Postileal

d) Pelvic

e) Subcaecal

3. Which of the following present as acute abdomen

a) Acute intermittent porphyria

b) Tabes

c) Pneumonitis of lower lobe

d)All

4. Oschner sherren regime is used in the management of-

a) Appendicular abscess

b) Chronic appendicitis

c) Appendicular mass

d) Acute appendicitis

5. Acute appendicitis is due to -

a) Faecoliths

b) Worms of ileo-caecal region

c) Streptococcal infections

d) Abuse of puragatives

e) None of the above

6. All of the following are early complications after appendectomy for acute appendicitis except-

a) ileus

b) Sterility

c) Intestinal obstruction

d) Pulmonary complications

7. Acute appendicitis is best diagnosed by -

a) History

b) Physical examination

c) X-ray abdomen

8. During appendectomy if it is noticed that the base of appendix is inflamed than further line of treatment is-

a) No appendectomy

b) No burying of stump

c) Hemicolectomy

d) Caecal resection

9. A 25 year old man presents with 3 days history of pain in the right lower abdomen and vomiting, patient's general condition is satisfactory and clinical examination reveals a tender lump the right iliac fossa. The most appropriate management in this case would be-

a) Immediate appendectomy

b) Exploratory laparotomy

c) Oschner Sherren regimen

d) External drainage

10. All of the following signs are not seen in acute appendicitis except -

a) Rovsing's

b) Murphy's sign

c) Boa's sign

d) Mack wen's sign

ГОУ ВПО «Смоленская государственная медицинская академия

Федерального агентства по здравоохранению и социальному развитию»

МЕТОДИЧЕСКИЕ УКАЗАНИЯ ДЛЯ СТУДЕНТОВ

ПО ДИСЦИПЛИНЕ хирургические болезни

EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL HERNIAS. STRANGULATED HERNIAS (differential diagnosis, clinical features, surgical tactics)

Составитель асс. А.Л.Буянов

Методические указания утверждены на методическом совещании кафедры госпитальной хирургии (протокол № 2 от 6 октября 2008 г.)

Зав. кафедрой______________(проф. С.А.Касумьян)

2008 г.

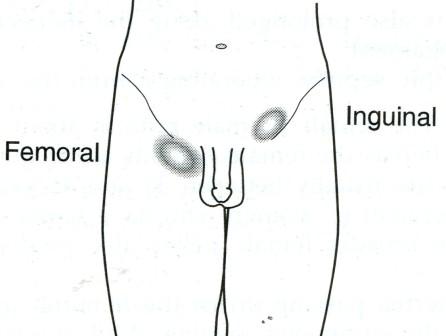

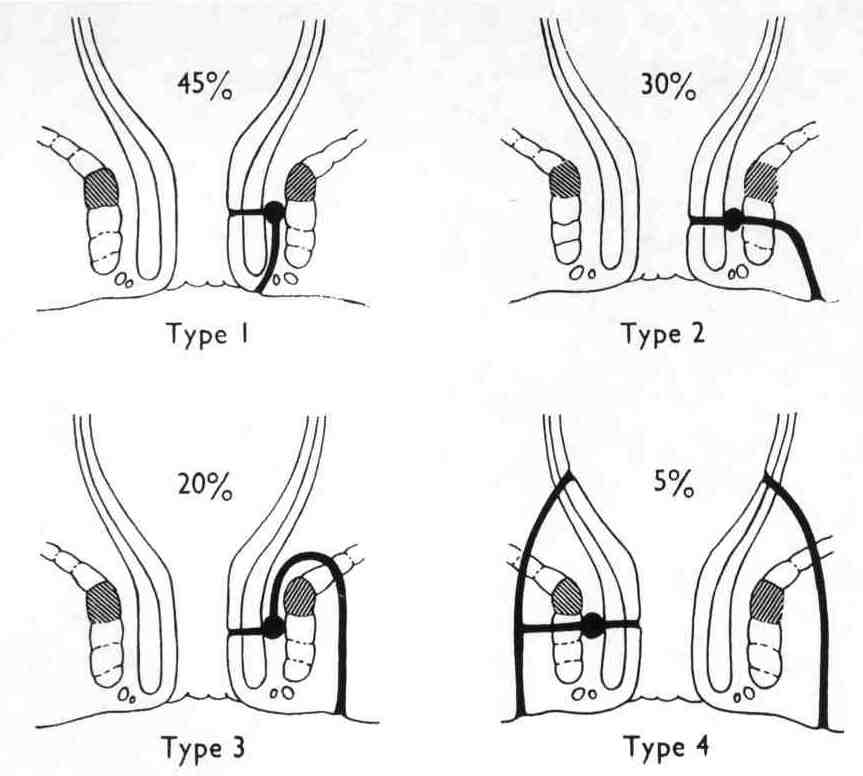

HERNIA

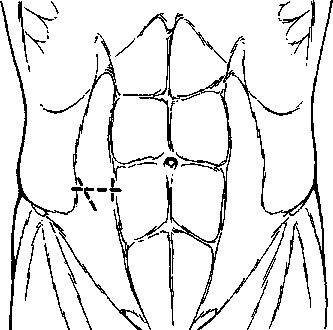

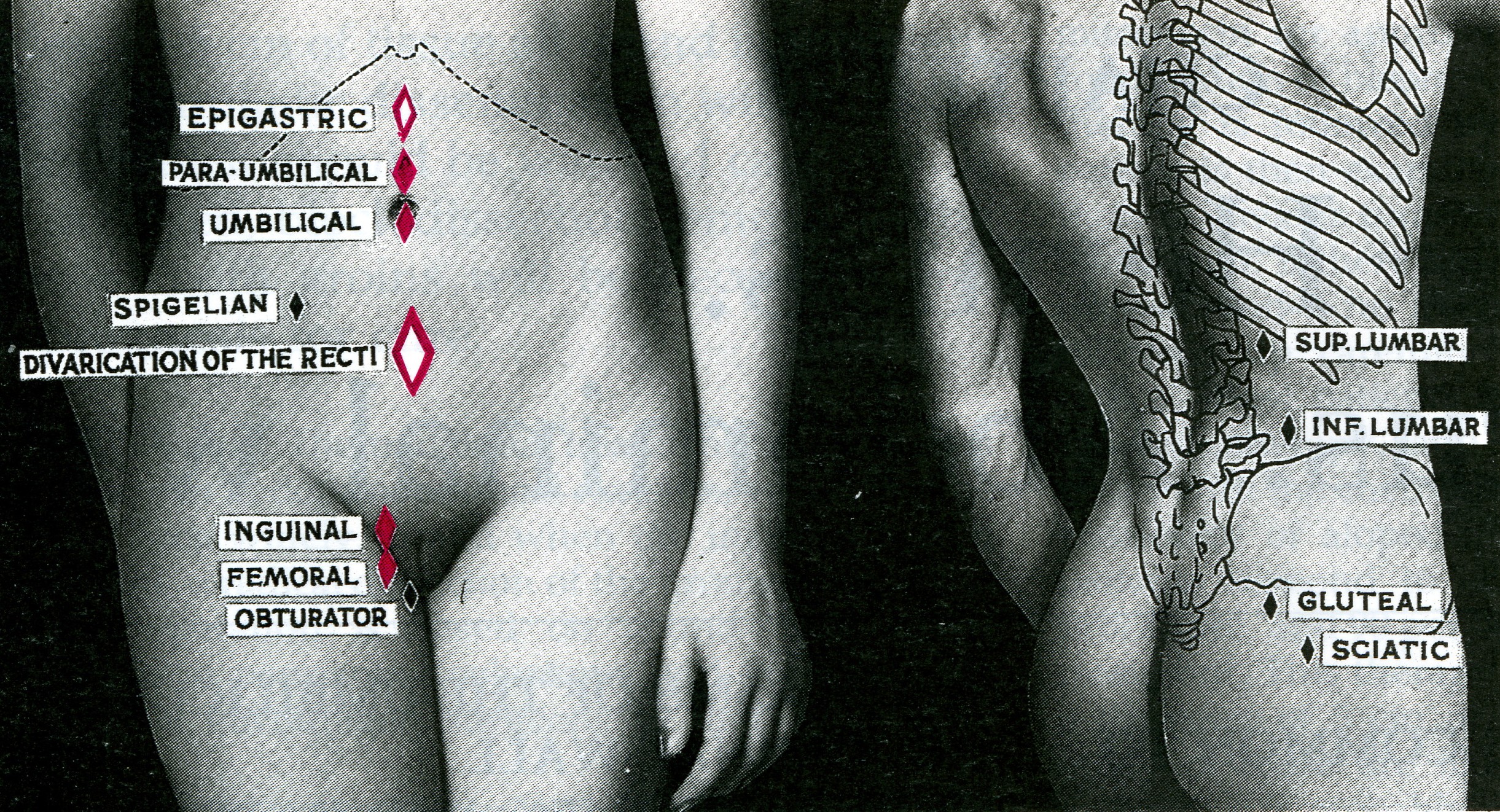

A hernia is the protrusion of a viscus or part of a viscus through an abnormal opening in the walls of its containing cavity. The external abdominal hernia is the commonest form of spontaneous hernia, and mostly of the inguinal, femoral and umbilical varieties, respectively 73, 17 and 8.5 per cent (Fig. 1). This leaves 1.5 per cent for the rarer forms. Incisional hernia is another increasingly common variety of external acquired hernia.

.

Fig. 1. External hernias.

Red = common; white = not unusual; black = rare

GENERAL FEATURES COMMON TO ALL HERNIAS

Aetiology. A powerful muscular effort or strain occasioned by lifting a heavy weight, or indeed any condition which raises intra-abdominal pressure, is liable to be followed by a hernia. Whooping cough is a predisposing cause in childhood, while a chronic cough, straining on micturition or on defaecation may precipitate a hernia in an adult. It should be remembered that the appearance of a hernia in an adult can be a sign of intra-abdominal malignancy. Premature infants have a high incidence of hernia.

Stretching of the abdominal musculature because of an increase in contents, as in obesity and in pregnancy, can be another factor. Fat acts as a kind of 'pile-driver' for it separates muscle bundles and layers, weakens aponeuroses, and favours the appearance of paraumbilical, direct inguinal, and hiatus hernias.

Inguinal hernia is commoner (x20) in men, and is probably present in 5-10 per cent of the normal male population. African men have a much higher incidence of inguinal hernia than Europeans.

Raised intraabdominal pressure (e.g. from ascites) can promote the development of all types of hernia.

Composition of a hernia. As a rule, a hernia consists of three parts - the sac, the coverings of the sac, and the contents of the sac.

The sac is a diverticulum of peritoneum consisting of mouth, neck, body and fundus. The neck is usually well defined, but in some direct inguinal hernias and in many incisional hernias there is no actual neck. The diameter of the neck is important, because strangulation of bowel is a likely complication where the neck is narrow, as in femoral and umbilical hernia.

The body of the sac varies greatly in size and is not necessarily occupied. In cases occurring in infancy and childhood the sac is gossamer thin. In long-standing cases, especially after years of pressure by a truss, the wall of the sac is comparatively thick.

Coverings are derived from the layers of the abdominal wall through which the sac passes. In long-standing cases they become atrophied from stretching and so amalgamated that they are indistinguishable one from another.

Contents. These can be almost any abdominal viscus, except the liver, but the commonest are:

• fluid, the most common content, derived from peritoneal exudate. It can also appear as a part of ascites, or as a residuum thereof. Blood-stained fluid accompanies strangulation;

• omentum = omentocele (syn. epiplocele);

• intestine = enterocele. Usually small intestine, but, in some instances, large intestine or the vermiform appendix;

• a portion of the circumference of the intestine = Richter's hernia;

• a portion of the bladder, or a diverticulum of the bladder, is sometimes present in addition to other contents in a direct inguinal, a sliding inguinal, and in a femoral hernia;

• ovary with or without the corresponding Fallopian tube;

• Meckel's diverticulum = Littre's hernia.

Classification

Irrespective of site, a hernia can be:

1. reducible

2. irreducible (Complication of 1)

3. obstructed

4. strangulated} (Complications of 2)

5. inflamed.

Reducible hernia. The hernia either reduces itself when the patient lies down, or can be reduced by the patient or by the surgeon. Note that intestine gurgles on reduction, and the first portion is more difficult to reduce than the last. Omentum is doughy, and the last portion is more difficult to reduce than the first. A reducible hernia imparts an expansile impulse on coughing.

Irreducible hernia. Here the contents cannot be returned to the abdomen and there is no evidence of other complications. It is brought about by adhesions between the sac and its contents or from overcrowding within the sac. Irreducibility without other symptoms is almost diagnostic of an omentocele especially in femoral and umbilical hernia. Note: Any degree of irreducibility predisposes to strangulation.

Obstructed hernia. (Syn. incarcerated hernia. The term 'incarceration' is often used loosely as an alternative to irreducibility, obstruction or strangulation. Because of its lack of precision, the term should not be used to describe a complicated hernia.) This is an irreducible hernia containing intestine which is obstructed from without or from within; but there is no interference to the blood supply to the bowel. The symptoms are less severe and the onset more gradual than is the case in strangulation, but more often than not the obstruction culminates in strangulation. Often no clear distinction can be made between obstruction and strangulation in hernias, so the safe course is to assume that strangulation is imminent and to treat accordingly.

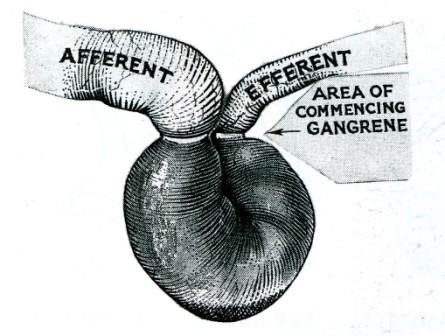

Strangulated hernia. A hernia becomes strangulated when the blood supply of its contents is seriously impaired, rendering gangrene imminent. Gangrene may occur as early as 5 or 6 hours after the onset of the first symptoms of strangulation. Although inguinal hernia is four times more common than femoral hernia, a femoral hernia is more likely to strangulate because of the narrowness of the neck of the sac and its rigid walls.

Pathology. The intestine is obstructed (except in a Richter's hernia, see below) and in addition its blood supply is constricted. At first only the venous return is impeded. The wall of the intestine becomes congested and bright red, and serous fluid is poured out into the sac. As the congestion increases, the intestine becomes purple in colour. As a result of increased intestinal pressure the strangulated loop becomes distended, often to twice its normal diameter. As venous stasis increases, the arterial supply becomes more and more impaired. Blood is extravasated under the serosa (an ecchymosis) and is effused into the lumen. The fluid in the sac becomes bloodstained. The shining serosa becomes dull and covered by a fibrinous, sticky exudate. By this time the walls of the intestine have lost their tone; they are flabby, and are very friable. The lowered vitality of the intestine favours migration of bacteria through the intestinal wall, and the fluid in the sac teems with bacteria. Gangrene appears first at the rings of constriction (Fig. 2), which become deeply furrowed and grey in colour, and then it appears in the antimesenteric border and spreads upwards, the colour varying from black to green according to the decomposition of blood in the subserosa. The mesentery involved by strangulation also becomes gangrenous. If the strangulation is unrelieved, perforation of the wall of the intestine occurs, either on the convexity of the loop or at the seat of constriction. Peritonitis spreads from the sac to the peritoneal cavity.

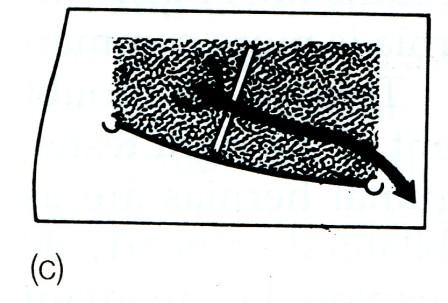

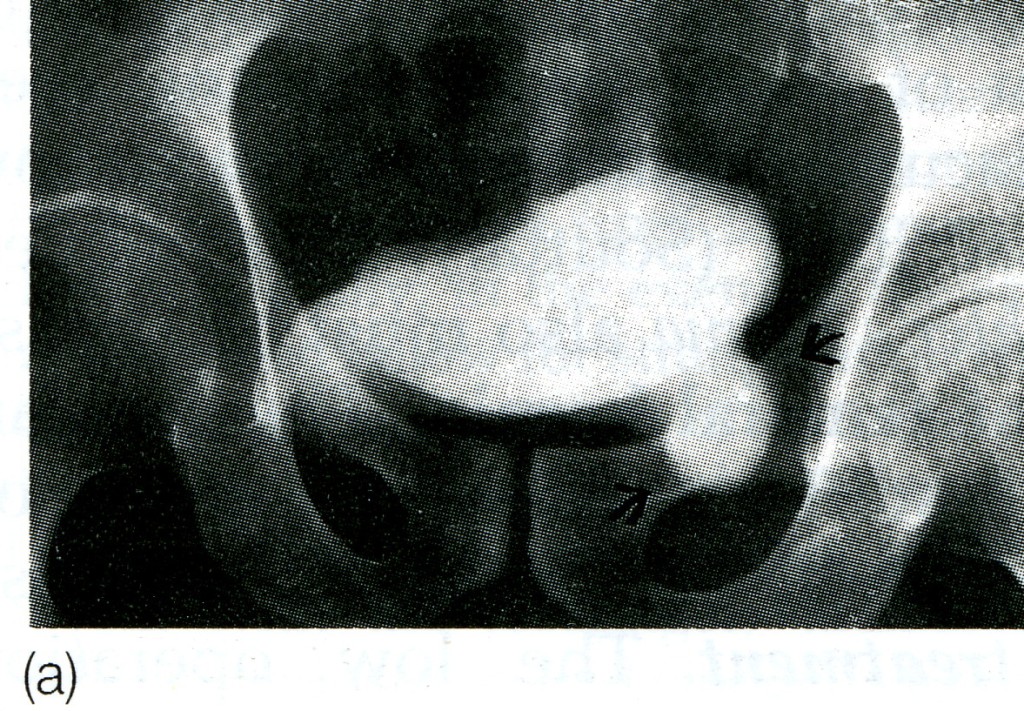

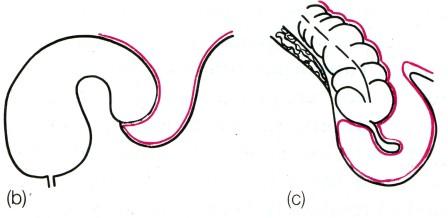

Fig. 2. Gangrene commences at the areas of constriction and then at the antimesenteric border.

Clinical features. Sudden pain, at first situated over the hernia, is followed by generalised abdominal pain, paroxysmal in character and often located mainly at the umbilicus. Vomiting is forcible and usually oft-repeated. The patient may say that the hernia has recently become larger. On examination, the hernia is tense, extremely tender, irreducible and there is no expansile impulse on coughing.

Unless the strangulation is relieved by operation, the paroxysms of pain continue until peristaltic contractions cease with the onset of gangrene when paralytic ileus (often the result of peritonitis) and toxic shock develop. Spontaneous cessation of pain is therefore of grave significance.

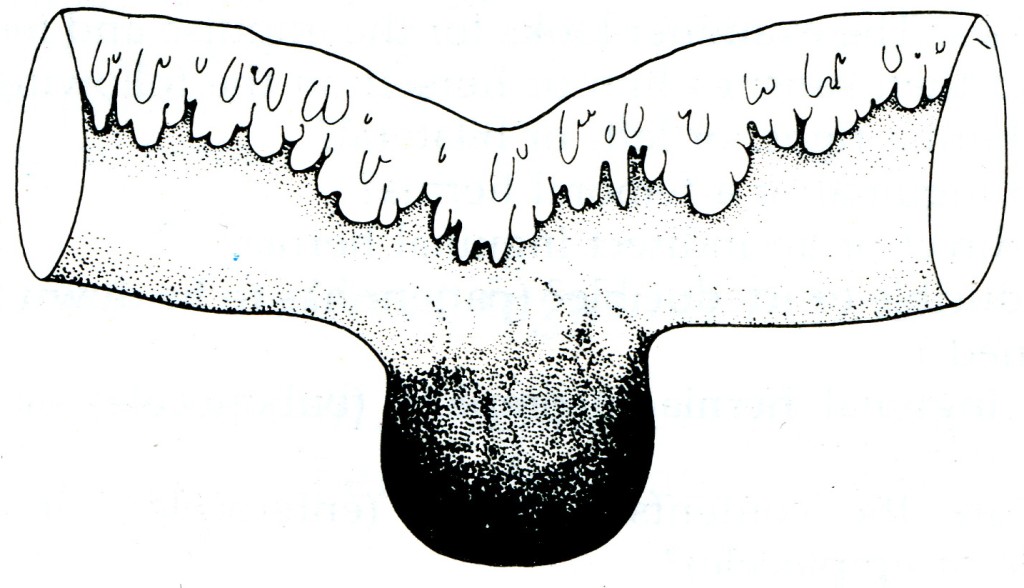

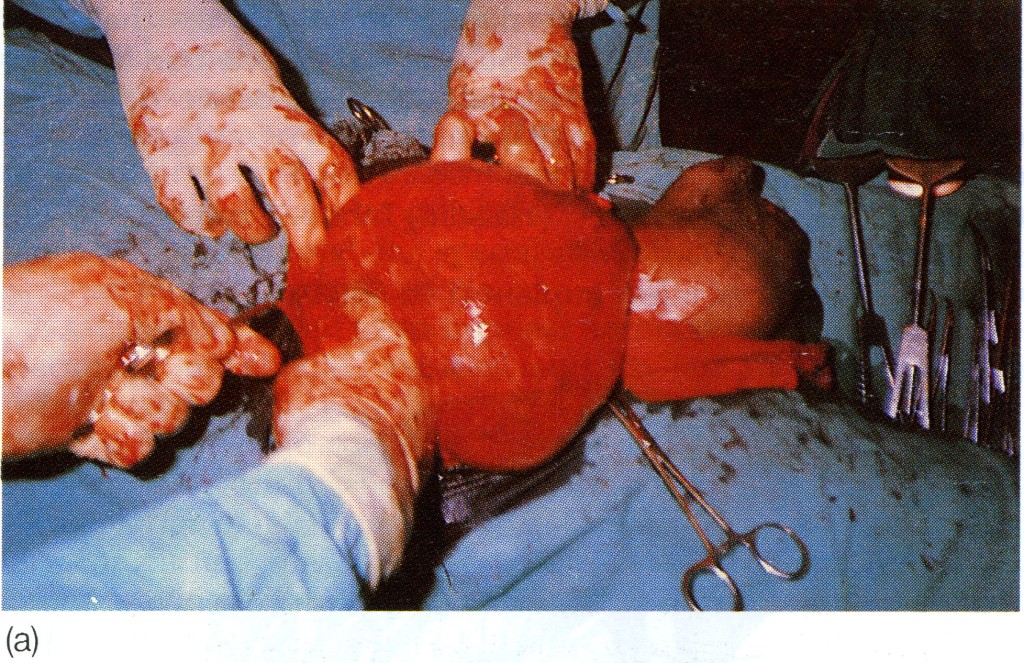

Richter's hernia is a hernia in which the sac contains only a portion of the circumference of the intestine (usually small intestine). It usually complicates femoral and, rarely, obturator hernias.

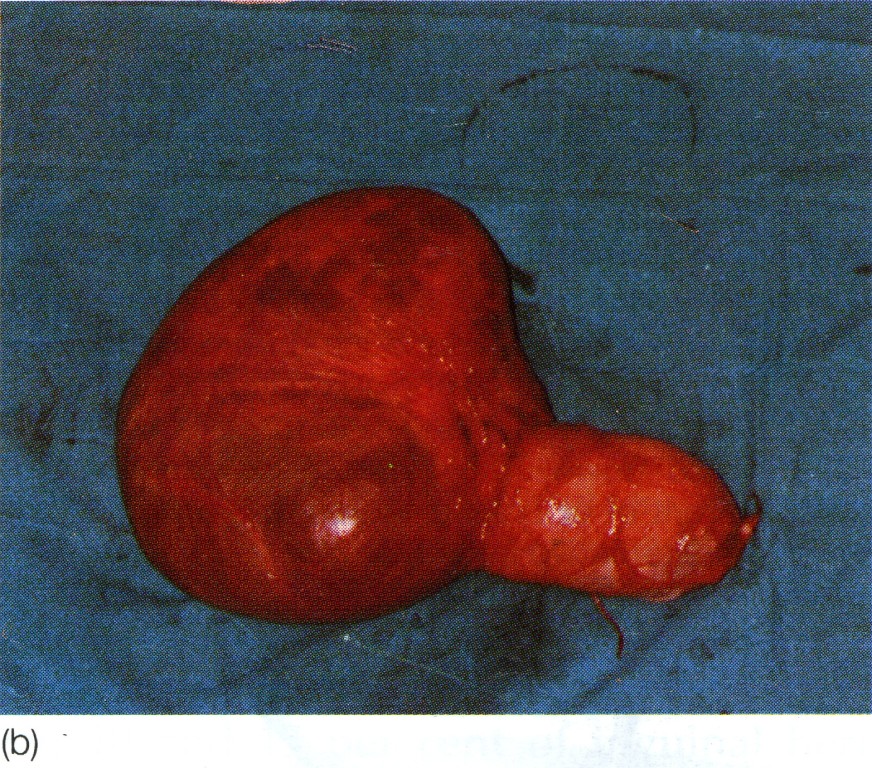

Strangulated Richter's hernia (Fig. 3) is particularly dangerous as operation is frequently delayed because the strangulated knuckle of bowel is small and there is no obstruction to the bowel lumen. A femoral site is common for this hernia and in a fat woman the local signs of strangulation are often not obvious. The patient may not vomit, or vomits only once or twice. Intestinal colic occurs, but the bowels are often opened normally or there may be diarrhoea; absolute constipation is delayed until paralytic ileus supervenes. For these reasons gangrene of the knuckle of bowel and peritonitis often have occurred before operation is undertaken.

Fig. 3. Gangrenous Richter's hernia from a case of strangulated femoral hernia.

Strangulated omentocele. The initial symptoms are in general similar to those of strangulated bowel. Vomiting and constipation may be absent. Unlike intestine, omentum can exist on a very meagre blood supply. The onset of gangrene is therefore correspondingly delayed, and it occurs first in the centre of the fatty mass. Unrelieved, a bacterial invasion of the dying contents of the sac will almost certainly occur. Infection is limited to the sac for days, and sometimes for weeks. In an inguinal hernia, infection usually terminates as a scrotal abscess, but extension of peritonitis from the sac to the general peritoneal cavity is always a possibility.

Inflamed hernia. Inflammation can occur from irritation or sepsis of the contents within the sac, e.g. acute appendicitis or salpingitis, also from external causes, e.g. from a sore caused by an ill-fitting truss. The hernia is tender but not tense, and the overlying skin becomes red and oedematous. Operation is necessary to deal with the cause.

INGUINAL HERNIA

Surgical anatomy

The superficial inguinal ring is a triangular aperture in the aponeurosis of the external oblique, and lies 1.25 cm above the pubic tubercle. The ring is bounded by a superomedial and an inferolateral crus joined by criss-cross intercrural fibres. Normally the ring will not admit the tip of the little finger (Fig. 4).

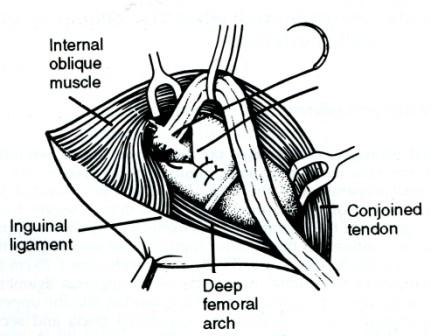

Fig. 4. The boundaries of the right inguinal canal. The inguinal ligament passes between the anterior superior iliac spine laterally, and the pubic tubercle medially, (a) The superficial layer, the external oblique aponeurosis, the crura of the external ring and the intercrural fibres; (b) the conjoined muscle (internal oblique and transversus) arching over the cord. Laterally the conjoined muscle lies superficial to the cord and the internal ring, then above the cord and medially, as the conjoined tendon, behind the cord; (c) the deepest layer which is the transversalis fascia (the fascial envelope of the abdomen). The inferior epigastric artery is shown lying medial to the internal ring.

The deep inguinal ring is a U-shaped opening in the transversalis fascia 1.25 cm above the midpoint of the inguinal ligament (Pouparfs ligament). The transversalis fascia is the fascial envelope of the abdomen, and the competency of the deep inguinal ring depends upon the integrity of this fascia.

The inguinal canal. In infants the superficial and deep inguinal rings are almost superimposed, and the obliquity of the canal is slight. In adults the inguinal canal, which is about 3.75 cm long, is directed downwards and medially from the deep to the superficial inguinal ring. In the male the inguinal canal transmits the spermatic cord, the ilioinguinal nerve, and the genital branch of the genito-femoral nerve. In the female the round ligament replaces the spermatic cord.

Boundaries of the inguinal canal. The best way to understand these is to study Fig. 4 (viewing the canal from the superficial to the deep layers as is seen at operation).

Thus, the boundaries of the inguinal canal are as follows:

Anteriorly. (Fig. 4a and b). External oblique aponeurosis. The conjoined muscle (mainly internal oblique) laterally.

Posteriorly. Inferior epigastric artery; fascia transversalis; conjoined tendon (internal oblique and transversus) medially (Fig. 4c and b).

Superiorly. Conjoined muscles (internal oblique and transversus) (Fig. 4b).

Inferiorly. Inguinal ligament (Fig. 4a, b and c).

Distinction between indirect and direct inguinal hernias, and a femoral hernia. An indirect inguinal hernia travels down the canal on the outer (lateral and anterior) side of the spermatic cord. A direct hernia comes out directly forwards through the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. While the neck of an indirect hernia is lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels, the direct hernia usually emerges medial to this except in the saddle-bag or pantaloon type, which has both a lateral and a medial component. An inguinal hernia can be differentiated from a femoral hernia by ascertaining the relation of the neck of the sac to the medial end of the inguinal ligament and the pubic tubercle, i.e. in the case of an inguinal hernia the neck is above and medial, while that of a femoral hernia is below and lateral (Fig.14). Digital control of the internal ring will help in distinguishing between an indirect inguinal hernia and a direct inguinal hernia, but final proof is only possible by displaying the anatomy at operation.

Indirect (syn. oblique) inguinal hernia

This is the most common of all forms of hernia (and see Aetiology). It is most common in the young whereas a direct hernia is most common in middle life or after. In the first decade of life inguinal hernia is more common on the right side in the male. This is no doubt associated with the deferred descent of the right testis. After the second decade, left inguinal hernias are as frequent as right. The hernia is bilateral in nearly 30 per cent of cases. If both sides are explored in an infant presenting with one hernia, the incidence of a patent processus vaginalis on the other side is 60 per cent. The condition usually occurs in a preformed sac (remains of processus vaginalis).

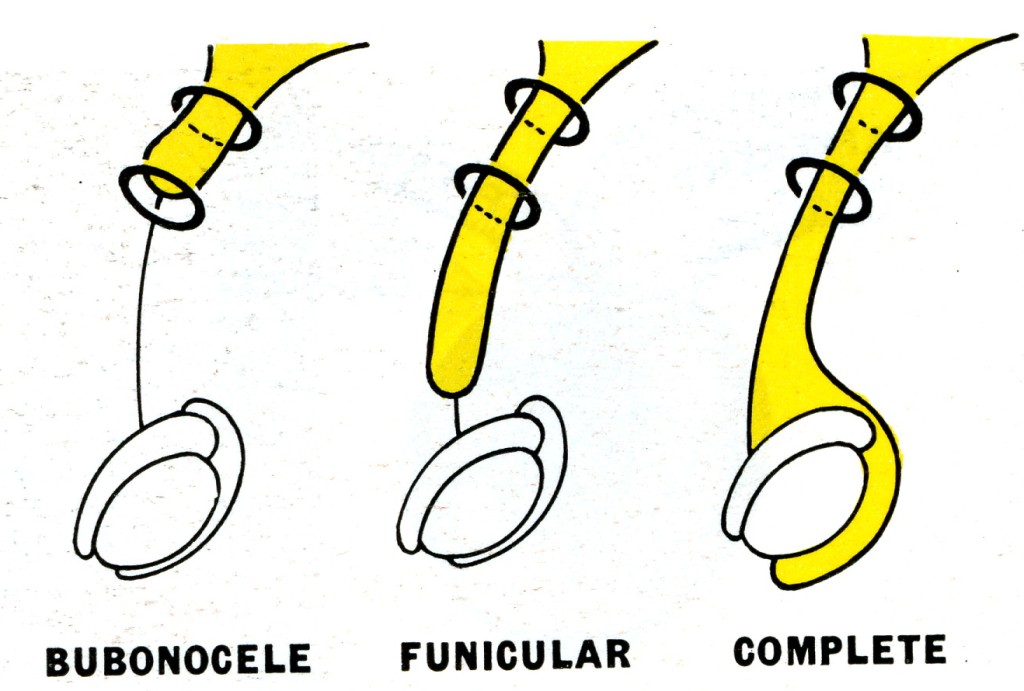

Three types of oblique inguinal hernia occur (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Types of oblique inguinal hernia. Bubon (Greek) = groin; funiculus (Latin) = a small cord.

Bubonocele. When the hernia is limited to the inguinal canal.

Funicular. The processus vaginalis is closed just above the epididymis. The contents of the sac can be felt separately from the testis, which lies below the hernia.

Complete (syn. scrotal). A complete inguinal hernia is rarely present at birth but is commonly encountered in infancy. It also occurs in adolescence or adult life. The testis appears to lie within the lower part of the hernia.

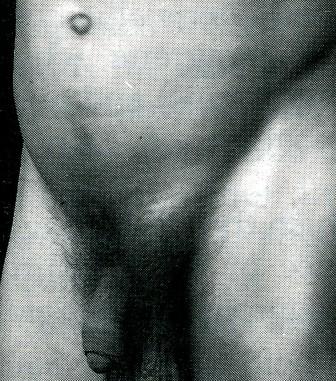

Clinical features. Occurring at any age, males are 20 times more commonly affected than females. The patient complains of pain in the groin or pain referred to the testicle when he is performing heavy work, or taking strenuous exercise. When he is asked to cough a transient bulging may be seen and felt, together with an expansile impulse (see below). When the sac is still limited to the inguinal canal, the bulge may be better seen by observing the inguinal region from the side or even looking down the abdominal wall while standing slightly behind the respective shoulder of the patient.

As an oblique inguinal hernia increases in size it becomes more obvious when the patient coughs, and persists until reduced (Fig. 6). As time goes on the hernia comes down as soon as the patient assumes the upright position. In large hernias there is a sensation of weight, and dragging on the mesentery may produce epigastric pain. If the contents of the sac are reducible, the inguinal canal will be found to be commodious.

Fig. 6. Oblique left inguinal hernia which became apparent when the patient coughed, and persisted until it was reduced when he lay down.

In infants the swelling appears when the child cries. It can be translucent in infancy and early childhood, but never in an adult. In young girls an ovary may prolapse into the sac as the pelvis has not fully enlarged to accommodate the organs.

Notes on the clinical examination. The clinician is seated in front of the patient who stands with his legs apart. He is instructed to look at the ceiling and to cough at the ceiling. If the hernia will come down, it usually does. The examiner looks for the impulse and feels for the impulse and then satisfies him or herself on the following points:

• Is the hernia right, or left, or bilateral?

• Is it an inguinal or a femoral hernia?

• Is it a direct or an indirect inguinal hernia?

• Is it reducible or irreducible? (patient has to lie down for this to be ascertained.)

• Is the inguinal hernia incomplete (bubonocele) or complete (scrotal)?

• What are the contents - bowel (enterocele), or omentum (omentocele or epiplocele)?

Differential diagnosis in the male (Fig. 7):

• a vaginal hydrocele

• an encysted hydrocele of the cord;

• spermatocele;

• a femoral hernia;

• an incompletely descended testis in the inguinal canal. An inguinal hernia is often associated with this condition;

• a lipoma of the cord. This is often a difficult, but unimportant, diagnosis. It is usually not settled until the parts are displayed by operation.

Note: examination using finger and thumb across the neck of the scrotum will help to distinguish between a swelling of inguinal origin and one which is entirely intrascrotal.

Differential diagnosis in the female:

• a hydrocele of the canal of Nuck is the commonest differential diagnostic problem;

• a femoral hernia.

Fig. 7. Large transilluminant cystic swelling present in right lower abdomen, extending down the inguinal canal into the scrotum, (a) Lesion being removed; (b) excised specimen. It is not possible to distinguish between a complex scrotal hernia, a hydrocele of the cord and a vaginal hydrocele in such a case before exposing the anatomy; in this case the lesion was an abdominoscrotal hydrocele (hydrocele-en-bisac). (Drs D. Pratep and R. Sahai, Jhansi, India.)

Treatment of indirect inguinal hernia

Operative treatment. Operation is the treatment of choice. It must be remembered that patients who have a bad cough from chronic bronchitis should not necessarily be denied operation, for these are the very people who are in danger of getting a strangulated hernia. As these patients are often elderly, the surgeon should consider giving extra strength to the repair by a synchronous orchidectomy and full closure of the internal ring. In adults, local, epidural or spinal, as well as general anaesthesia can be used.

Inguinal herniotomy is the basic operation which entails dissecting out and opening the hernial sac, reducing any contents and then transfixing the neck of the sac and removing the remainder. It is employed either by itself or as the first step in a repair procedure (herniorrhaphy). By itself it is sufficient for the treatment of hernia in infants, adolescents and young fit adults who have good inguinal musculature. In fact, any attempts at repair in such cases are meddlesome and do more harm than good.

In infants it is not necessary to open the canal, as the internal and external rings are superimposed. Excellent results are obtained. The operation should be done in the morning and the child allowed home in the evening. Usually there is no need for the child to stay in hospital and 'the best nurse is the mother'. Although bilateral inguinal hernias are present in 30 per cent of cases of male infantile indirect inguinal hernias, it is probably not justified to explore the other side of cases of unilateral presentation, most of whom do not have a hernia on the normal side. In female infants, in whom bilateral sacs are very common, bilateral exploration is justified.

Herniotomy and repair (herniorrhapy). This operation consists of (1) excision of the hernial sac (above), plus (2) repair of the stretched internal inguinal ring and the transversalis fascia, and (3) further reinforcement of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. Stages (2) and (3) must be achieved without tension, usually by 'darning' with a monofilament suture material such as polypropylene. Fascial flaps, or synthetic mesh implants, are employed when the deficiency of the posterior wall is extensive.

Operative procedures

General principles. Excision of the hernial sac (adult herniotomy).

Before the skin incision in large inguinoscrotal hernias, the usual antiseptic preparation of the skin should not be extended to the perneal aspect of the scrotum, for, by so doing, severe bacterial contamination of the operation site is likely. The operation approach should be confined to the anterior inguinal and scrotal aspects. An incision is made in the skin and subcutaneous tissues 1.25 cm above and parallel to the medial two-thirds of the inguinal ligament. In large irreducible herniae the incision is extended into the upper part of the scrotum. After dividing the superficial fascia and securing complete haemostasis, the external oblique aponeurosis and the superficial inguinal ring are identified. The external oblique aponeurosis is incised in the line of its fibres, and the structures beneath are carefully separated from its deep surface before completing the incision through the superficial inguinal ring. In this way the ilioinguinal nerve is safeguarded. With the inguinal canal thus opened, the upper leaf of the external oblique aponeurosis is separated by blunt dissection from the internal oblique. The lower leaf is likewise dissected until the inner aspect of the inguinal ligament is seen. The cremasteric muscle fibres are divided longitudinally to open up the subcremasteric space and display the spermatic cord, which is then lifted out.

Excision of the sac. The indirect sac is easily distinguished as a pearly white structure lying on the upper side of the cord and, when the internal spermatic fascia has been incised longitudinally, it can be dissected out and then opened between haemostats.

Variations in dissection. If the sac is small (e.g. bubonocele) it can be freed in toto. If it is of the long funicular or scrotal type, or is extremely thickened and adherent, the fundus need not be sought. The sac is freed and divided in the inguinal canal. Care must be taken to avoid damage to the vas and the spermatic artery, including the blood supply to the epididymis.

An adherent sac can be separated from the cord by first injecting saline under the posterior wall from within. A similar tactic is used when dissecting the gossamer sac of infants and children.

Reduction of contents. Intestine or omentum is returned to the peritoneal cavity. Omentum is often adherent to neck or fundus of the sac; if to the neck, it is freed, and if to the fundus of a large sac, it may be transfixed, ligated and cut across at a suitable site. The distal part of omentum, like the distal part of a large scrotal sac, can be left in situ (the fundus should not, however, be ligated).

Isolation and ligation of the neck of the sac. Whatever type of sac is encountered, it is necessary to free its neck by blunt and gauze dissection until the parietal peritoneum can be seen on all sides. Only when the extraperitoneal fat is encountered and the inferior epigastric vessels are seen on the medial side has the dissection reached the required limit. If it has not been done already, the sac is opened. The finger is passed through the mouth of the sac in order to make sure that no bowel or omentum is adherent. The neck of the sac is transfixed and ligated as high as possible, and the sac is excised 1.25 cm below the ligature.

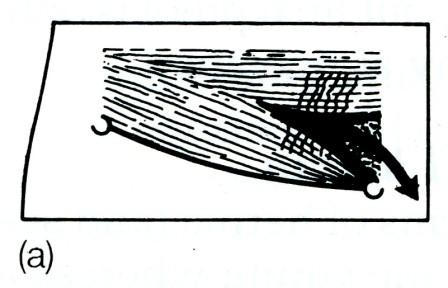

Repair of the transversalis fascia and the internal ring. When the internal ring is weak and stretched, and the transversalis fascia is bulging, the repair should include the Lytle method of repairing and narrowing the ring with lateral displacement of the cord (Fig. 8), or the Toronto (Shouldice) method, whereby the ring and fascia are incised and carefully separated from the deep inferior epigastric vessels and extraperitoneal fat before an overlapping repair ('double breasting') of the lower flap behind the upper flap is effected. This repair using monofilament continuous suturing or darning materials (e.g. polypropylene, poly amide, wire) and avoiding tension is the basis for obtaining good results.

Fig. 8. The Lytle method of repair of the stretched internal inguinal ring which should be narrowed to admit the tip of the little finger. Lateral displacement of the cord is often advantageous, (fitter F.S.A. Dora/7, FRCS, Bromsgrove, England.)

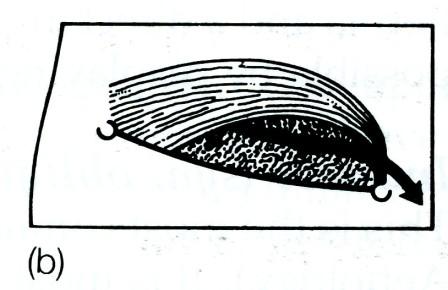

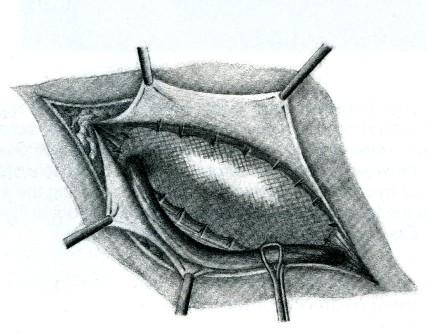

Reinforcement of the posterior inguinal wall is achieved by approximating without tension the tendinous and aponeurotic part of the conjoined muscle to the pubic tubercle (and, according to some, to Astley Cooper's iliopectineal ligament) and to the undersurface of the inguinal ligament. Care is taken not to pick up the same tendinous bundle for each suture. Suturing of muscle bundles is of no value. The suturing method includes a choice between:

• simple interrupted stitches (Bassini type);

• darning (Fig. 9);

• a rectus-relaxing incision (Halsted-Tanner) combined with either of the above;

• a Dacron or other mesh implant (Fig. 10).

Other techniques include overlapping the external oblique behind the cord (making it lie subcutaneously). Special care is needed to avoid excessive narrowing of the new external ring which would jeopardise the vascular supply to, and the venous return from, the testis.

F ig.

9. The first layer of the two-layer darn of the posterior wall of the

inguinal canal. The darning is conducted from the pubic tubercle up

to and above the deep inguinal ring and back to the starting point.

The

darning is kept fairly loose, and it forms a lattice upon which

fibrous tissue is laid down. The external oblique aponeurosis is

reunited either in front of or behind the cord. Meticulous asepsis is

essential. Inset an alternative lattice darn.

ig.

9. The first layer of the two-layer darn of the posterior wall of the

inguinal canal. The darning is conducted from the pubic tubercle up

to and above the deep inguinal ring and back to the starting point.

The

darning is kept fairly loose, and it forms a lattice upon which

fibrous tissue is laid down. The external oblique aponeurosis is

reunited either in front of or behind the cord. Meticulous asepsis is

essential. Inset an alternative lattice darn.

F ig.

10. Dacron mesh reinforcement. The mesh is attached to the inguinal

ligament, the coverings of the pubis, the rectus sheath and the

conjoined aponeurosis and tendon. It is also fashioned by a slot

laterally above and below the cord at the internal ring.

ig.

10. Dacron mesh reinforcement. The mesh is attached to the inguinal

ligament, the coverings of the pubis, the rectus sheath and the

conjoined aponeurosis and tendon. It is also fashioned by a slot

laterally above and below the cord at the internal ring.

Specific types of repair. Herniotomy. This is particularly recommended for infants and young, athletic men (see above).

Inguinal repairs. The Shouldice (Toronto) repair is recommended for most indirect inguinal hernias. For very large hernias, a mesh may need to be used. In elderly men, orchidectomy should be considered. Extraperitoneal repairs are useful when the abdominal wall is very weak and recurrence is to be expected. Bilateral hernias, or combined inguinal and femoral hernias, and above all, recurrent hernias are often treated best by this method. Laparoscopic repair does not permit repair of the musculoaponeurotic structures of the canal although a mesh can be put in. It is still an unproven technique which should be used for special indications, e.g. serious risk of cardiorespiratory complications.

A satisfactory repair of an inguinal hernia can be done under local anaesthetic and should have a nil mortality rate and a recurrence rate of 1 per cent.

Sepsis is the main complication of inguinal hernia repair and can be avoided by careful technique (see below).

Completion of operation. If possible the cremasteric muscle should be reconstituted: the external oblique is directly sutured or overlapped leaving a new external ring which will accommodate the tip of the little finger.

A truss is used when operation is contraindicated because of cardiac, pulmonary, or other systemic disease, or when operation is refused. The hernia must be reducible. A rat-tailed spring truss with a perineal band to prevent the truss slipping will, with due care and attention, control a small or moderate-sized inguinal hernia. A truss must be worn continuously during waking hours, kept clean, and in proper repair, and renewed when it shows signs of wear. It must be applied before the patient gets up and while the hernia is reduced. A properly fitting truss must control the hernia when the patient stands with his legs wide apart, stoops, and coughs violently. If it does not it is a menace, for it increases the risk of strangulation.

Infants and trusses. Special inflatable rubber trusses, formerly popular for the control of an infant's hernia, are rarely used. Provided urgent admission is not required for sudden irreducibility, the parents are advised to wait for operation until the infant is at least 3 months old.

Direct inguinal hernia

Between 10 and 15 per cent of inguinal hernias are direct. Over half of these are bilateral.

A direct inguinal hernia is always acquired. The sac passes through a weakness or defect of the transversalis fascia in the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. In some cases the defect is small and closely related to the insertion of the conjoint tendon, while in others there is a generalised bulge. Often the patient has poor lower abdominal musculature, as shown by the presence of elongated bulgings (Malgaigne's bulges). Women practically never develop a direct inguinal hernia (Brown). Predisposing factors are a chronic cough, straining, and heavy work. Damage to the ilioinguinal nerve (e.g. by previous appendicectomy) is another known cause.

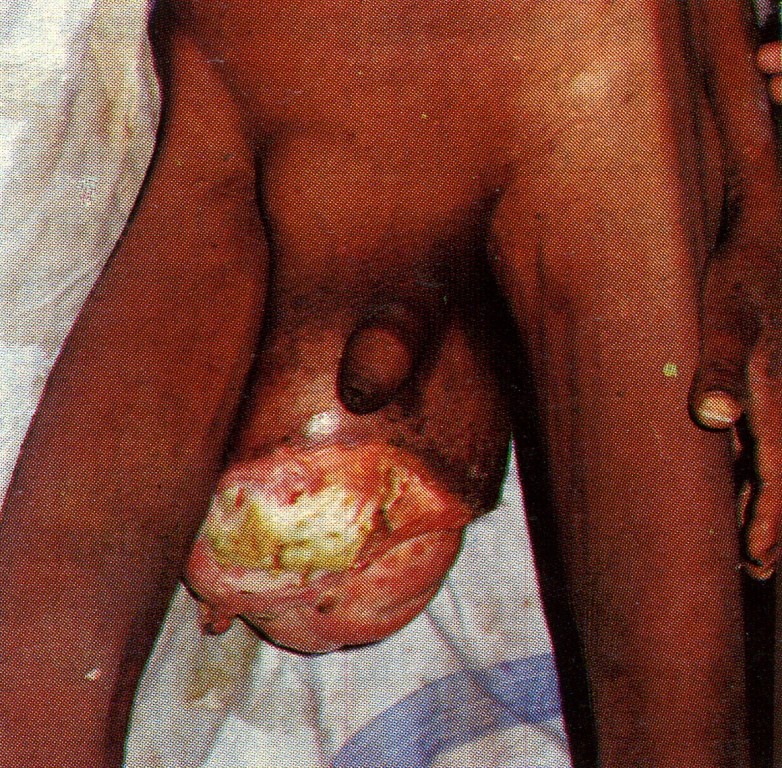

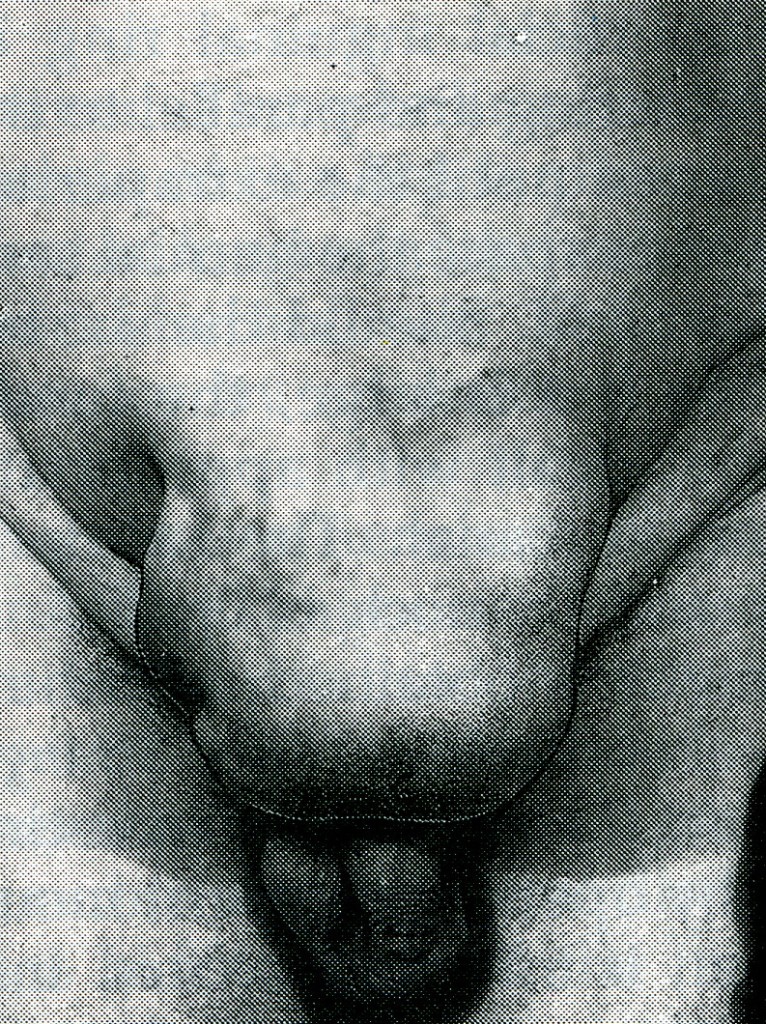

Direct hernias sometimes attain a large size and descend into the scrotum (Fig. 11) but this is rare. In contradistinction to an oblique inguinal hernia, a direct inguinal hernia lies behind the spermatic cord. The sac is often smaller than the hernial mass would indicate, the protruding mass mainly consisting of extraperi-toneal fat. As the neck of the sac is wide, direct inguinal hernias rarely strangulate.

Fig. 11. Shows a huge inguinal hernia (direct) which has descended into the scrotum, and the overlying skin has become gangrenous and sloughed away. (Dr Anupam Rai, Jabalpur, India.)

Funicular direct inguinal hernia (syn. prevesical hernia) is a narrow-necked hernia of prevesical fat and a portion of the bladder that occurs through a small oval defect in the medial part of the conjoined tendon just above the pubic tubercle. It occurs principally in elderly males, and occasionally it becomes strangulated. Unless there are definite centra-indications, operation should always be advised.

Dual (syn. saddle-bag; pantaloon) hernia. Here there are two sacs which straddle the inferior epigastric artery, one sac being medial and the other lateral to this vessel. The condition is not a rarity, and is a cause of recurrence, one of the sacs having been overlooked at the time of operation.

Operation for direct hernia. The principles of repair of direct hernia are the same as those of an indirect hernia with the exception that the hernial sac need not be removed, for after it has been dissected free from surrounding structures it is inverted into the abdomen and the transversalis fascia repaired in front of it. Some form of reconstruction of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal is necessary, Polypropylene darns, and Dacron mesh insertions are popular (Figs. 9 and 10).

Complications of herniorrhaphy are:

• wound sepsis (especially due to faulty technique);

• haematoma;

• lymphocele (commoner after operations for femoral hernia);

• wound sinus (especially when foreign tissue is used for the repair);

• division of spermatic cord (especially in infantile hernia operation);

• testicular ischaemia (especially after large or recurrent hernia repairs);

• testicular atrophy;

• hydrocele;

• nerve entrapment

- pain

- parasthesia or numbness;

• recurrence (especially after operations for large hernias in elderly males or sepsis);

• general

- retention of urine

- respiratory complications

- thromboembolic complications.

Strangulated inguinal hernia

(Pathological and clinical features are described earlier in this chapter.)

Strangulation of an inguinal hernia occurs at any time during life, and in both sexes. Oblique inguinal hernias strangulate commonly; the direct variety but rarely owing to the wide neck of the sac. Sometimes a hernia strangulates on the first occasion that it descends; more often strangulation occurs in patients who have worn a truss for a long time, and in those with a partially reducible or irreducible hernia. Strangulation occurs most frequently in large hernias in elderly patients, which is an excellent reason for an aggressive approach to hernia repair in younger patients.

In order of frequency, the constricting agent is:

1. the neck of the sac;

2. the external abdominal ring (in children especially);

3. rarely adhesions within the sac.

Contents. Usually small intestine is involved in the strangulation; the next most frequent content is omentum; sometimes both are implicated. For large intestine to become strangulated in an inguinal hernia is of the utmost rarity, even when the hernia is of the sliding variety.

Strangulation during infancy. The incidence of strangulation is 4 per cent (Gross), and the ratio of females to males is 5:1. More frequently the hernia is irreducible but not strangulated. In most cases of inguinal hernia occurring in female content of the sac is an ovary, or an ovary plus its Fallopian tube.

Treatment of strangulated inguinal hernia. The treatment of strangulated hernia is by emergency operation. (The danger is in the delay, not in the operation' - Astley Cooper.)

If dehydration and collapse are present, intravenous fluid replacement and gastric aspiration for 1-3 hours are invaluable. It is absolutely essential to make sure that the stomach is emptied just before commencing the anaesthetic. The passing of a large-bore stomach tube is the best way of preventing vomiting, drowning, and cardiac arrest during the induction. The bladder must also be emptied, if necessary by a catheter. Suitable broad-spectrum antimicrobials are i.v.

Inguinal herniotomy for strangulation. An incision is made over the most prominent part of the swelling. The external oblique aponeurosis is exposed, and the sac, with its coverings, is seen issuing from the superficial inguinal ring. In all but very large hernias it is possible to deliver the body and fundus of the sac together with its coverings and (in the male) the testis onto the surface. Each layer covering the anterior surface of the body of the sac near the fundus is incised, and if possible it is stripped off the sac. The sac is then incised, the fluid therein is mopped up or aspirated very thoroughly, for it can be highly infected. The external oblique aponeurosis and the superficial inguinal ring are divided. Returning to the sac, a finger is passed into the opening, and employing the finger as a guide, the sac is slit along its length. If the lies at the superficial inguinal ring or in the inguinal canal, it is readily divided by this procedure. When the constricting agent is at the deep inguinal ring, by applying haemostats to the cut edge of the neck of the sac and drawing them downwards, and at the same time retracting the internal oblique upwards, it may be possible to continue slitting up the sac over the finger beyond the point of constriction. When the constriction is too tight to admit a finger, a grooved director is inserted and the neck of the sac is divided with a hernia knife in an upward and inward direction, i.e. parallel to the inferior epigastric artery, under vision. Once the constricting agent has been divided, the strangulated contents can be drawn down. Devitalised omentum is excised after being securely ligated, by interlocking stitches if bulky. Viable intestine is returned to the peritoneal cavity. Doubtfully viable and gangrenous intestine is dealt with. If the hernial sac is of moderate size and can be separated easily from its coverings, it is excised and closed by a purse-string suture. When the sac is large and adherent, much time is saved by cutting across the sac. Having tied or sutured the neck of the sac a repair can be made if the condition of the patient permits, but synthetic implants should be avoided because of the risks of infection.

Conservative measures. These are only indicated in infants. Children are given a sedative and then slung to a Balkan beam1 or to the bedrail by their feet (the judgment of Solomon position) for no longer than 3 hours. In 75 per cent of cases reduction is effected and there appears to be no danger of gangrenous intestine being reduced (Irvine Smith). Manual reduction of irreducible and strangulated hernias under sedation is permissible in infants in whom the risk of intestinal gangrene appears to be almost nonexistent for many hours. For all other cases, vigorous manipulation (taxis) has no place in modern surgery, and is mentioned only to be condemned. Its dangers include:

• Contusion or rupture of the intestinal wall.

• Reduction-en-masse. The sac together with its contents, is pushed forcibly back into the abdomen; and as the bowel will still be strangulated by the neck of the sac, the symptoms are in no way relieved` (Treves).

• Reduction into a loculus of the sac.

• The sac may rupture at its neck and its contents are reduced, not into the peritoneal cavity, but extraperitoneally.

Maydl's hernia (syn. hernia-in-W) is rare. The strangulated loop of the W lies within the abdomen, thus local tenderness over the hernia is not marked. At operation two comparatively normal-looking loops of intestine are present in the sac. After the obstruction has been relieved, the strangulated loop will become apparent if traction is exerted on the middle of the loops occupying the sac.

Inguinal hernia recurrence

Only by using a meticulous technique, principally concentrating on the repair of the transversalis fascia and the internal ring, can a recurrence rate of less than 2 per cent be achieved. Recurrences through the repair tend to occur within 2 years. In a few cases false recurrences occur, i.e. another type of hernia occurs -direct after indirect, femoral after direct or indirect. To the patient it is a recurrence!

The spermatic cord as a barrier to effective closure of the inguinal canal. In the elderly patient, removal of the testis and cord aids in an effective repair in the case of recurrent inguinal hernia, sliding hernia, and some large direct hernias. The signed permission of the patient must always be obtained beforehand.

Sliding hernia (syn. hernie-en-glissade) (Fig. 12)

As a result of slipping of the posterior parietal peritoneum on the underlying retroperitoneal structures, the posterior wall of the sac is not formed of peritoneum alone, but by the sigmoid colon and its mesentery on the left, the caecum on the right and, sometimes, on either side by a portion of the bladder. It should be clearly understood that the caecum, appendix, or a portion of the colon wholly within a hernial sac does not constitute a sliding hernia. A small-bowel sliding hernia occurs once in 2000 cases; a sacless sliding hernia once in 8000 cases.

Fig. 12. Sliding hernia, (a) Cystogram showing bladder involving a left inguinal hernia, (b) Diagram of the same, (c) Caecum and appendix in right sliding hernia.

Clinical features. A sliding hernia occurs almost exclusively in males. Five out of six sliding hernias are situated on the left side; bilateral sliding hernias are exceedingly rare. The patient is nearly always over 40, the incidence rising with the weight of years. There are no clinical findings that are pathognomonic of a sliding hernia, but it should be suspected in every large globular inguinal hernia descending well into the scrotum. Large intestine is commonly present in a sliding hernia (or caecum and appendix in a right-sided case).

Occasionally large intestine is strangulated in a sliding hernia; more often nonstrangulated large intestine is present behind the sac containing strangulated small intestine.

Treatment. A sliding hernia is impossible to control with a truss, and as a rule the hernia is a cause of considerable discomfort. Consequently operation is indicated, and the results generally are good.