- •Chapter 5 The Labor Market for College Coaches

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 Trends in Compensation

- •5.2 Is a Coach a ceo?

- •5.3 What Determines a Coach’s Salary?

- •5.4 Is the Labor Market for Coaches Competitive?

- •5.5 Winner-Take-All Labor Markets (The Economics of Superstars)

- •5.6 Risk Aversion

- •5.7 The Winner’s Curse

- •5.8 Ratcheting

- •5.9 Old Boy Networks

- •5.10 Chapter Summary

- •5.11 Key Terms

- •5.12 Review Questions

- •5.13 Discussion Questions

- •5.14 Internet

- •5.15 References

5.5 Winner-Take-All Labor Markets (The Economics of Superstars)

Universities, especially those attempting to upgrade their athletics program, often compete against one another to hire the “messiah coach,” the person who will transform a losing program, or a relatively unknown program, into a high profile program where winning is the rule not the exception. The “messiah” is typically a person from the coaching community who is perceived to be vastly superior compared to her peers, she is, in other words, a superstar. Superstars exist in many professions: athletes, movie stars, novelists, trial attorneys, CEOs, scientists‑even economists. The labor market for these stars is intriguing.

Imagine a competitive labor market consisting of many buyers and sellers; a market in which all the potential employees (the sellers) have virtually the same amount of talent or productivity. Microeconomic theory suggests the equilibrium wage or salary paid to each person would be nearly identical (the variance in the wage distribution would be small). But what if it turned out that the distribution of wages was skewed in such a manner that a small percentage of those employed earned a disproportionate amount of the total earnings? For example, suppose Chef Suzy, Chef Pierre, and 98 other chefs make delicious cherry-chocolate cheesecakes. Suzy’s dessert is judged by buyers to be slightly superior to those produced by Pierre and the other chefs. If all 100 chefs produce the same number of cheesecakes during a given time period, but Suzy’s are slightly better, we expect Suzy’s wages to exceed everyone else’s by a small amount — say, $550 per week vs. $500. But what if it turns out that Suzy is paid $2200 per week, not $550, even though no one would claim that her cheesecakes are four times better than Pierre’s or those produced by the other chefs. This concentration of earnings among a few (whom we refer to as the superstars) is one part of what economists refer to as a winner-take-all market.6 The other part is that individuals’ earnings are determined by relative not absolute performance.

Economists define a superstar in this market as “a worker whose compensation level far exceeds those of all of the other workers within the organization even though often his/her skill level is only slightly higher than the next most productive worker; the differential in salary is magnified relative to the differential in productivity” (Benjamin, Gunderson, & Riddell, 2002, p. XX). By absolute standards, Suzy produces the same number of cheesecakes as everyone else (the only difference is that each cheesecake she makes is slightly better). But because she competes in a winner-take-all market, “slightly better” allows her to capture the lion’s share of the earnings.

We observe winner–take-all markets in many settings, including the film industry. For example, the estimated median earnings of salaried actors in 2002 was $23,470, yet actors such as Tom Cruise or John Travolta command $20 million for a single film appearance. From your perspective, or that of the average movie viewer, are Cruise and Travolta 852 times better actors than someone earning the median salary?7 Is it possible that those on the demand side (the buyers) may consider potential television and film actors to be imperfect substitutes; that is, buyers perceive some sellers (the actors) to be of higher quality then they really are. How these perceptions develop and persist over time is difficult to answer; nevertheless, we will offer one possibility in the next section — risk aversion on the part of buyers.

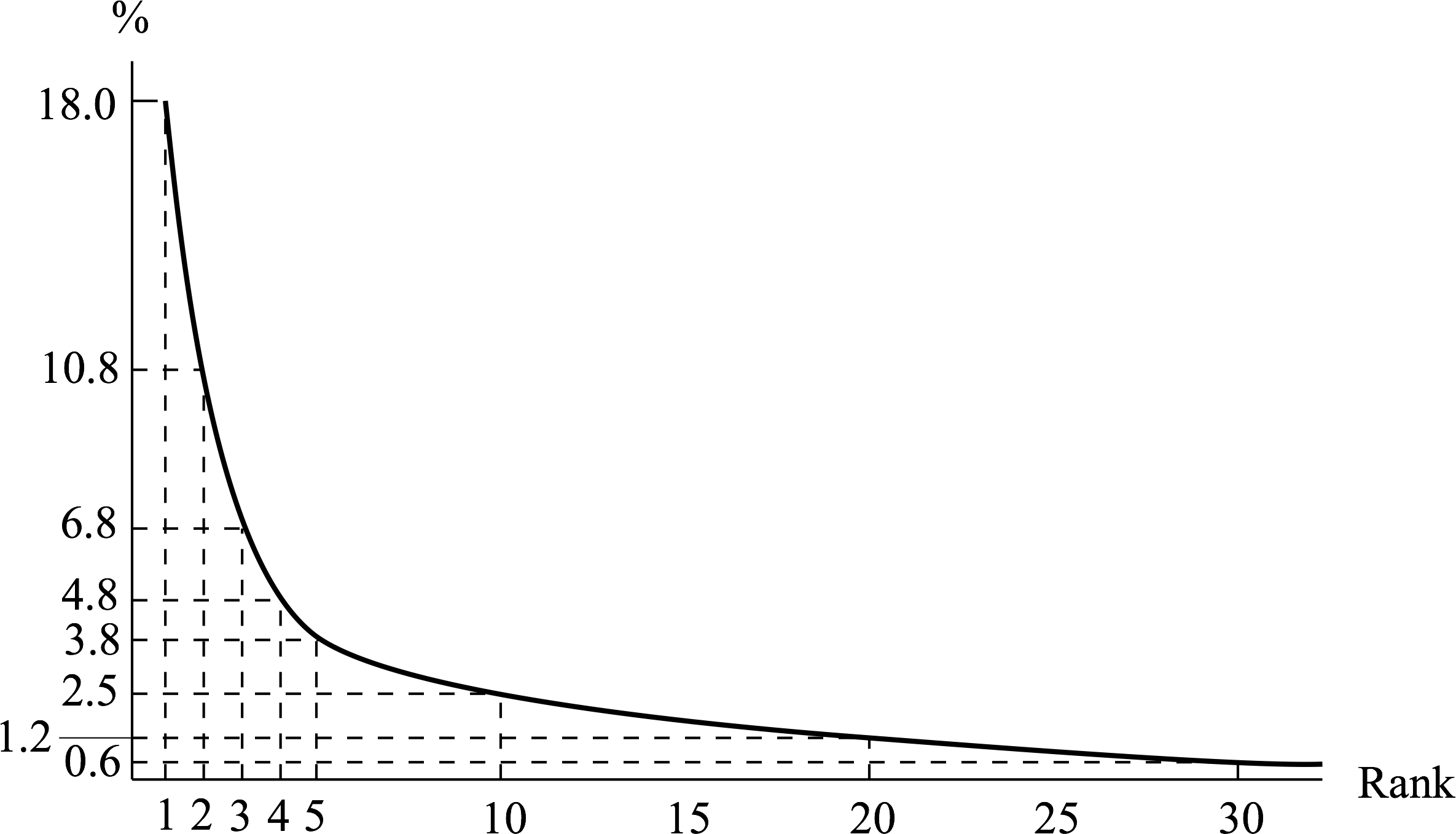

Why do winner-take-all markets flourish? One possible answer, clearly applicable to athletic contests like golf and tennis tournaments, is that the prize structure is purposely skewed to begin with; economists refer to this as a rank-order tournament. Thus, the woman who finishes 10th at Wimbledon does not receive a prize 1/10th that of the woman who finished first but rather a prize perhaps 1/50th in size (Figure 5.1 illustrates this).8 Suppose a prize system based on absolute performance was used instead. A person who finished in nth place would receive 1/n of the tournament winnings that the first place finisher does. Would the quality of the competition really be any different?9

Figure 5.1 Prize Money Shares by Tournament Rank, 2004 PGA Championship

Source: http://www.pga.com/pgachampionship/2004/prize_money.html

What can we conclude from the economics of superstars and its application to college coaches? First, as in other professions, there are superstars among the coaching community — Pete Carroll or Mike Krzyzewski — who earn salaries and total compensation packages far beyond those of their peers. Second, it suggests that individuals who have similar levels of productivity may receive substantially different salaries from one another, even if they coach in the same sport. We are not suggesting that the productivity of Coaches Carroll and Krzyzewski is identical to all other coaches, only that it may be perceived to be far greater than it really may be. In practical terms, this means in some cases universities may be paying their coaches far more than necessary to attract a person of comparable experience and talent (keeping in mind that those universities are reaping substantial monopsonistic rents). Third, it reinforces the arms race among universities, a topic we introduced in Chapter 2 and one we return to in the next chapter.10