- •Chapter 10 the role of government

- •10.1. Government and the American Economy

- •10.2. The Growth of Government

- •10.3. How does the Federal Government Spend Its Money?

- •10.4. What are the Sources of

- •10.5. State And Local Finances

- •10.6. Taxes, Taxes, Taxes...

- •10.7. Who Ought to Pay Taxes

- •10.8. Types of Taxes: Progressive, Proportional and Regressive

- •10.9. Tax Incidence: Who Really Pays a Tax?

- •10.10. How Can Our Tax System Be Improved?

- •10.11. Budget Deficit and the National Debt

- •10.12. Proposals to Reduce the Deficit

10.12. Proposals to Reduce the Deficit

Everyone knows how to reduce the budget deficit. Higher taxes and less government spending would achieve the goal. Yet deficits have occurred in every year since 1969. Why haven't they disappeared? To see why, consider efforts to shrink the budget deficit over the last 10 years.

The Recent Record. In 1985, Congress passed the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act, commonly known as Gramm-Rudman-Hollings. The act was supposed to eliminate the deficit in five years by requiring the government to meet annual deficit targets. Each successive year would have a lower target until the deficit was gone in 1991. To carry out the law, the government would forecast its deficit when a new budget was adopted at the beginning of each budget year in October. If the budget didn't meet the deficit target for the coming year, spending cuts would occur automatically to achieve the deficit target.

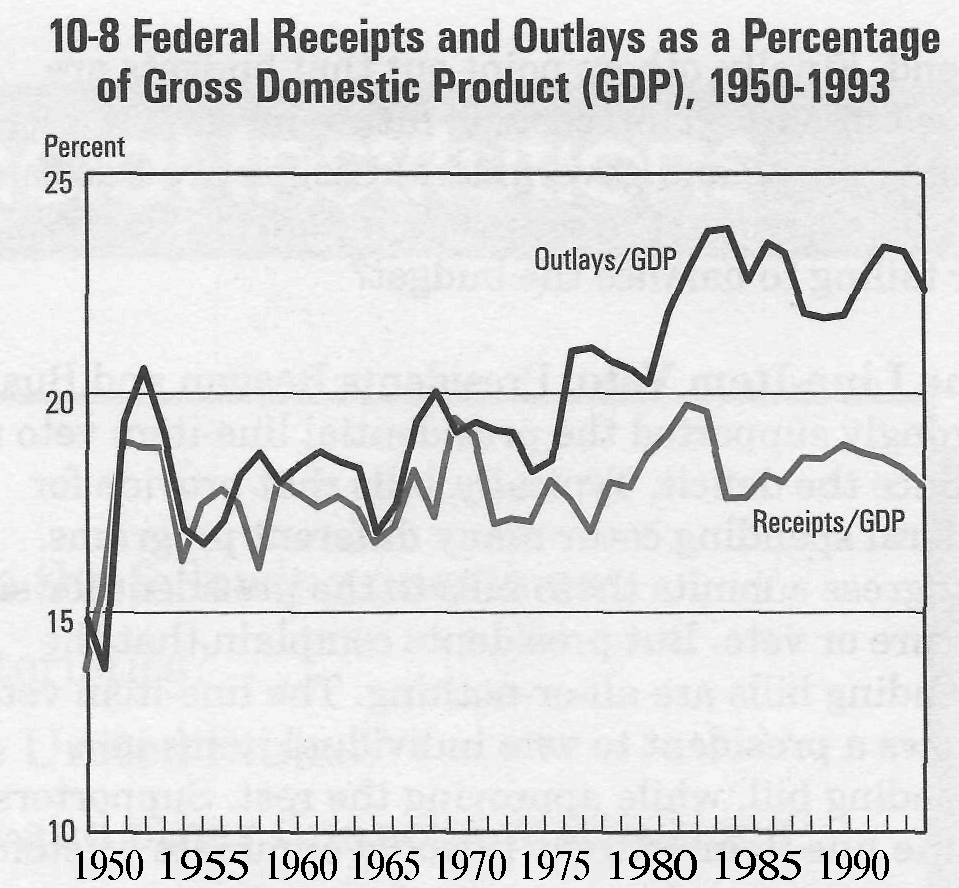

The Supreme Court declared part of the act unconstitutional in 1986. Congress revised it the following year. In the process Congress changed each year's deficit target and extended the deadline for a balanced budget to 1993. Despite the law, deficits continued, as Chart 10-8 shows. The top line is federal outlays as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) from 1950 to 1993. The bottom line is federal receipts as a percentage of GDP. The gap between the outlays line and the receipts line shows the deficit since 1969.

Why didn't the act reduce the deficit as planned? One reason was that forecasts of each year's deficit were always too low. Optimistic forecasts made each budget look like it would meet the deficit target for the coming year. The government would then continue its spending and taxing policies and end up exceeding the deficit target at the end of the year. In 1990, for example, the actual deficit was $221 billion, more than twice the targeted level of $100 billion.

The government missed all of its deficit targets, so President Bush and Congress agreed to revise Gramm-Rudman-Hollings in 1990. The Budget Enforcement Act of that year was supposed to place tighter controls on government spending in the following ways:

• Maximum amounts - or caps - were put on discretionary spending programs. Discretionary programs are those for which Congress decides how much to spend each year. They account for about 38 percent of federal outlays, of which national defense is approximately half.

• Any new mandatory programs must be offset by

an increase in taxes or a reduction in other mandatory spending. Mandatory programs are those which require Congress to follow spending based on inflation and other economic factors. Mandatory spending programs include retirement programs, income security, health care, and other benefits to individuals. (Net interest payments on the national debt are excluded.)

• Tax cuts trigger across-the-board spending cuts.

Besides these restraints on spending, the act contained the tax increases described on page 127. Still, Chart 10-8 shows that the gap between spending and receipts was large even after the Budget Enforcement Act of 1990. In response, President Clinton proposed additional taxes and spending restraints in the budget he submitted to Congress in 1993. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the budget would reduce the deficit by $433 billion over the five-year period of 1994-1998. The reduction contained $192 billion of spending restrictions and $241 billion of higher taxes.

Because of its higher taxes, President Clinton's budget was very controversial. In August 1993 the House of Representatives barely approved it by a vote of 218-216. The Senate voted only 51-50 in its favor, with Vice President Gore casting the tie-breaking vote.

The Balanced-Budget Amendment. Some people have suggested that the budget could be brought into balance with a constitutional amendment. The balanced-budget amendment they propose would require that budgets approved by Congress provide for total outlays that are no greater than total receipts.

Many supporters of a balanced-budget amendment argue that Congress lacks the self-discipline to control its spending. Look at the record, they say, and you'll see that Congress has used higher taxes to raise spending, not reduce the deficit. They want a constitutional amendment to force Congress to make the difficult choices needed to balance the budget.

Many opponents of the amendment argue that Congress, as democratically elected representatives of the people, has the authority and ability to look after the nation's fiscal affairs. Some add that it would be foolish to balance the budget if our economy is in a slump. At these times, deficit spending might help the economy recover. Other opponents think such an amendment might only help Congress raise additional taxes to fund whatever it decides to spend. Finally, others point out that budgets are based in part on forecasts of future income. If a forecast is wrong and government receipts are less than predicted, would the courts then punish Congress for failing to balance the budget?

The Line-Item Veto. Presidents Reagan and Bush strongly supported the presidential line-item veto to reduce the deficit. Typically, bills that provide for federal spending cover many different programs. Congress submits these bills to the president for signature or veto. But presidents complain that the spending bills are all-or-nothing. The line-item veto allows a president to veto individual items in a spending bill, while approving the rest. Supporters of the line-item veto say it would eliminate wasteful spending. Those who oppose it say it would transfer spending powers from Congress to the president, weakening the constitutional principle of checks and balances.

While not endorsing the line-item veto, President Clinton has voiced support for a similar, weaker measure called an expedited rescission authority. The president now has the authority to rescind (cancel) the funding of specific items. But unless more than 50 percent of Congress votes in agreement within 45 days, the funds are restored to the budget. To expedite means to speed something up. So expedited rescission authority would shorten the period within which Congress must decide to vote on the president's action.

Summary

The economic role of government (local, state, and federal) has grown dramatically in recent years. Federal participation in the economy has outpaced the other two, so that now federal spending is about twice that of the state and local governments combined.

There are many reasons for government growth. One is the enormous expense involved in meeting the nation's past, present, and future defense needs. In addition, the public expects the government to fill many important and expensive roles in the economy-from providing health care to building roads and highways to supporting public education.

The principal items of expense to the federal government are direct payments to individuals, national defense, and interest on the national debt. Education is the single-largest item of expense to states and localities.

Taxes provide the principal source of income to all levels of government. Income taxes are the principal source of federal tax income. State and local governments rely on sales, income, and property taxes.

When government receipts equal expenditures, the budget is balanced. When receipts exceed expenditures, the difference represents a surplus; and when they are less than expenditures, the difference is a deficit. Federal deficits have pushed the total national debt to record levels. Whether these deficits will prove to be harmful to the nation's economic health has been a matter of sharp controversy, and identifying strategies for reducing the deficit is a major challenge facing our political leaders.

The Underground Economy

When he finished painting their apartment, Ralph asked the Vegas to pay him in cash, rather than by check.

"I don't have that much cash on hand, Ralph, but if you can come back in an hour or so, I'll cash a check down at the bank," Mr. Vega replied.

"That'll be fine," Ralph said. "I'll be back later."

"I wonder if Ralph is part of the underground economy?" Maria Vega asked.

"You mean, you wonder if he is declaring his cash income when he pays his taxes?" Umberto Vega asked in reply.

"I guess so," Maria said. "And let me tell you, Umberto, that bothers me. Failing to declare one's income is dishonest. It's illegal, for another. And, it seems to me that if some people are paying less than their fair share of taxes, others have to pay more, I don't like the idea of paying more than my fair share just because someone else decided to cheat the government."

Painters who work for cash are not the only people who hide their income from the government: lawyers may exchange their services for automobile repairs and hair stylists may quietly pocket their tips without reporting them as income to the IRS. Countless numbers are part of the underground economy. The underground economy refers to any exchanges of goods and services that go unreported.

How Large Is the Underground Economy? Obviously, it is difficult to measure how much income people are hiding from the government. Economists, however, have been able to make some educated guesses. Since most of the underground economy is based on cash, then where more cash is in circulation than is necessary for normal business, it must be going to finance unreported transactions. Using cash in circulation and other data, economists estimate that the underground economy is 5 percent to 15 percent of the nation's GDP. That would mean that in 1992 the underground economy was between $300 billion and $900 billion dollars!

The Underground Economy Leads to Higher Taxes and\or Larger Deficits. Since the money earned in the underground economy is untaxed, the government loses billions of dollars in potential revenue. This can only be made up through higher taxes on the honest part of the population, increased debt, or reduced spending.

The Underground Economy Can Lead to Misguided Policies. Later chapters will describe the things government can do to improve economic conditions. But government policies are based on the best available information. Since economic activity in the underground economy is unreported, the lack of information can lead government policy makers to make incorrect decisions on how to deal with economic problems.

Paul Samuelson and Milton Friedman

Two Views of the Proper Role of Government in the Economy

Paul Samuelson and Milton Friedman are two of America's most distinguished economists. In recognition of

their achievements, Samuelson was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1970 and Friedman in 1976. Both spent most of their professional lives on the faculty of major universities (Samuelson at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Friedman at the University of Chicago). Given their similarities, one would think that the two also would hold similar views on economic issues. Nothing could be further from the truth. Some of their sharpest differences occur over government's proper role in the economy.

Classical economists, like Adam Smith, recognized the need for government to provide goods and services (like national defense) that would not or could not be provided by the private sector. But they urged that government's role be kept small. Professor Samuelson has argued that too many of the problems the classical economists wanted to leave to the marketplace were externalities and not subject to the laws of supply and demand. He argued it was up to government to establish goals for the economy and use its powers to solve problems related to issues such as public health, education, and environmental pollution.

Milton Friedman sees things differently. Like the classical economists, he regards supply and demand as the most powerful and potentially beneficial of economic forces. The best that government can do to help the economy, in Friedman's view, is to keep its hands off business and allow the market to "do its thing." The minimum wage laws are a case in point. Whereas Samuelson endorses minimum wage laws to help low-income workers, Friedman says they harm the very people they were designed to help. He argues, by increasing labor costs, minimum wage laws make it too expensive for many firms to hire low-wage workers. As a result, those who might otherwise be employed are not hired at all.

Samuelson endorses the concept of government-sponsored programs such as public housing and food stamps to reduce poverty. Friedman, though, prefers giving low-income families additional income and allowing them to use the funds to solve their problems without government interference. To apply this concept, Friedman suggested the "negative income tax." The graduated income tax takes an increasing amount in taxes as one's income rises. The negative income tax would apply a sliding scale of payments to those whose income from work fell below a stated minimum.