- •Chapter 10 the role of government

- •10.1. Government and the American Economy

- •10.2. The Growth of Government

- •10.3. How does the Federal Government Spend Its Money?

- •10.4. What are the Sources of

- •10.5. State And Local Finances

- •10.6. Taxes, Taxes, Taxes...

- •10.7. Who Ought to Pay Taxes

- •10.8. Types of Taxes: Progressive, Proportional and Regressive

- •10.9. Tax Incidence: Who Really Pays a Tax?

- •10.10. How Can Our Tax System Be Improved?

- •10.11. Budget Deficit and the National Debt

- •10.12. Proposals to Reduce the Deficit

10.8. Types of Taxes: Progressive, Proportional and Regressive

Most taxes can be classified as progressive, proportional, or regressive.. A progressive tax takes a larger percentage of a higher income and smaller percentage of a lower income. The federal income tax is the best-known example of a progressive tax.

A proportional tax takes the same percentage of all income, regardless of size. So, for example, a proportional income tax of 10 percent would cost a person with a $10,000 income $1,000 in taxes, and a person with a $100,000 income $10,000 in taxes.

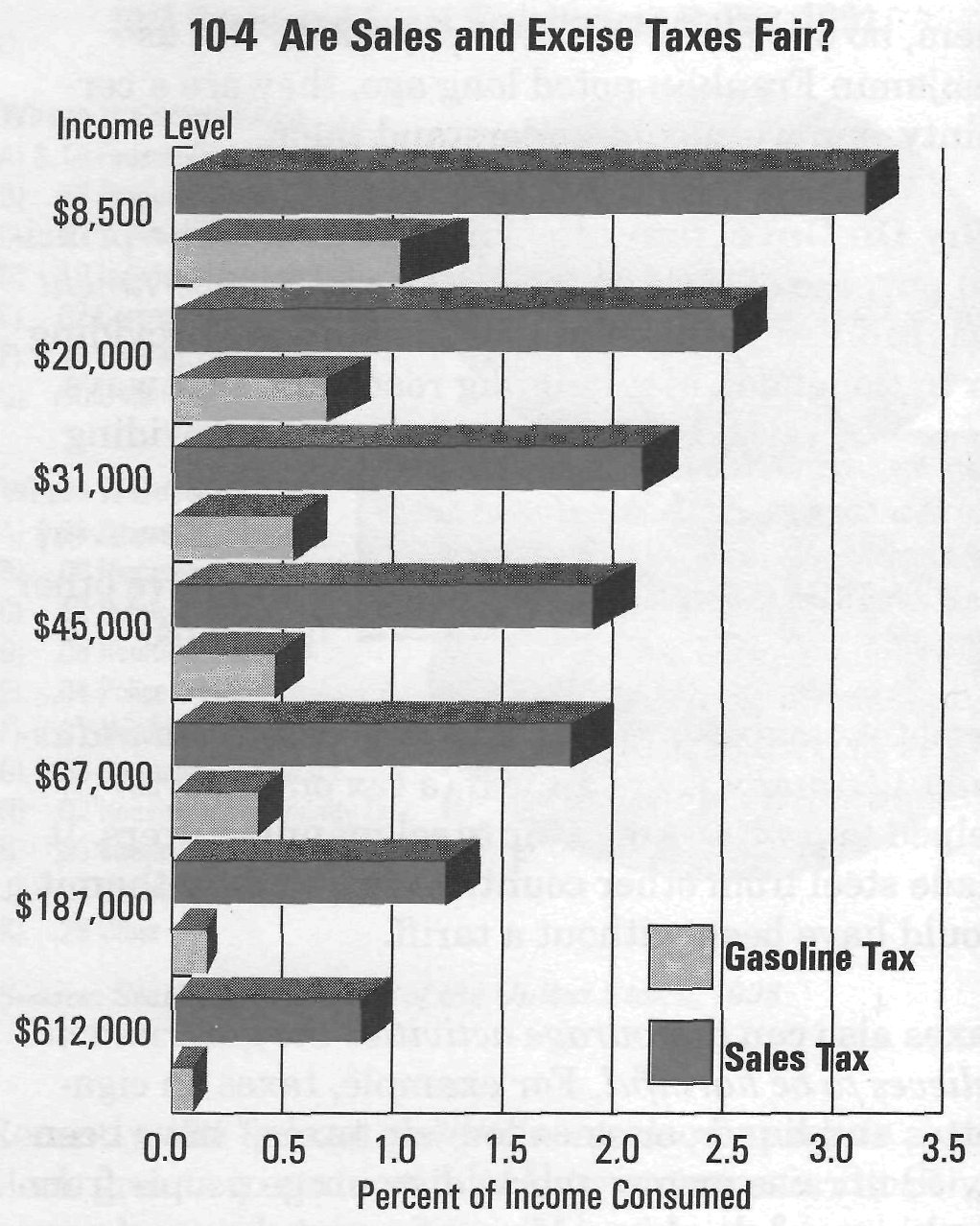

A regressive tax is one that takes a higher percentage from people with low-incomes than from people with high-incomes. Although they are not based on income, sales taxes have a regressive effect. For example, a low-income family and a high-income family buy $500 refrigerators with a sales tax of 8 percent. They both pay a $40 sales tax. But the $40 represents a higher percentage of the low-income family's income than that of the high-income family.

Which Tax is the Fairest? Few would say that a regressive tax is fair. Those who favor the ability-to-pay principle would support a progressive tax, and possibly the proportional tax. There are some, however, who argue that the proportional tax is not fair. The proportional tax seems to be fair because everyone pays the same rate. Miss Rich, with her income of $100,000 pays 10 times as much as Mr. Poor, who has an income of $10,000. Mr. Poor, however, can barely get by on $10,000; he needs every penny he earns. Miss Rich, on the other hand, can pay a tax of $10,000 and still have $90,000 left over to save or invest. Although her tax was 10 times as large as Mr. Poor's, she did not suffer as much in paying it.

In analyzing the impact of taxes on individuals, economists often concentrate on discretionary income - the amount that a person has left after buying necessities (food, clothing, shelter, medical care, transportation, etc.) Assume that Mr. Poor has $1,000 left after having met all his needs. By levying a tax of $1,000, the government has taken 100 percent of Poor's discretionary income. What about Miss Rich? Let's say that she needs $50,000 to meet all of her needs (as she defines them), and that she has $50,000 left as a discretionary income. The government taxes $10,000 of this, or only 20 percent. She still has $40,000 left for luxuries, savings, and investments. By focusing on discretionary income, we find that the proportional tax can have a regressive effect!

10.9. Tax Incidence: Who Really Pays a Tax?

To evaluate a tax, it is important to know who will really have to pay it. Tax incidence refers to the individual or business that will actually pay a tax. With income taxes and fees such as tolls, determining the incidence a tax is fairly easy.

The burden of paying some taxes, however, can be avoided if the one responsible can pass the cost on to someone else. This process is known as tax-shifting. When taxes are passed on to consumers, they are shifted forward. Similarly, taxes are shifted backward if suppliers or workers who produce the products are forced to assume the burden.

Whether taxes are shifted forward, backward, or not at all usually depends on the elasticity of demand for a particular product. As you learned, the elasticity of demand is a measure of how eager consumers are to buy a particular good or service and the availability of substitutes.

The more eager buyers are, the less elastic their demand will be. When demand is relatively inelastic, it is easier for sellers to shift taxes to buyers. For example, when a trucking company pays taxes on the fuel it purchases, it can shift much of the cost of those taxes forward to its customers. Sometimes, by negotiating for lower prices or paying lower wages, a company can shift the burden of taxes backward to a supplier or its own employees. In many cases consumers bear much of the cost of sales or excise taxes. Sales taxes usually seem small relative to the price of any good, and consumers seldom base their purchasing decision on the extra tax they may have to pay.

Typically, cigarettes, alcohol, jewelry, and hotel rooms also have inelastic demand curves. As a result, consumers end up paying a bigger part of the taxes on these things.