- •Lexicology as a linguistic discipline.

- •Lexicology as a brunch of linguistics. Types of Lexicology.

- •The connection of lexicology with other linguistic disciplines. Methods of lexicological research.

- •General problems of the theory of the Word.

- •1.Lexicology as a brunch of linguistics. Types of Lexicology.

- •The notion of the linguistic sign.

- •2.The connection of lexicology with other linguistic disciplines. Methods of lexicological research.

- •The Transformational Analysis

- •3. General problems of the theory of the word.

- •Lecture 2 Etymological characteristics of Modern English vocabulary

- •1. Native words in English.

- •2. Borrowings in English vocabulary. Classification of borrowings.

- •Classification of borrowings according to the language from which they were borrowed

- •French borrowings

- •Italian borrowings.

- •German borrowings.

- •Holland borrowings.

- •Russian borrowings.

- •3. Etymological doublets

- •Lecture 3 Morphological structure of English words. Wordbuilding

- •1. Morphological structure of English words.

- •2. Different ways of wordbuilding in English.

- •3. Productive ways of word-building in English.

- •Lecture 4 Semantic structure of English words. Semantic processes.

- •1. Semasiology. Word-meaning. Lexical and grammatical meaning.

- •2. Polysemy in Modern English, its role and sources. Homonymy, Synonymy. Antonyms in me.

- •3. Semantic processes. Change of meaning.

- •Lecture 5 homonymy and synonymy in modern english

- •1. Homonymy in English. The sources of homonymy

- •Sources of Homonymy

- •2. Classification of Homonyms

- •4. Classification of synonyms

- •Ideographic (which he defined as words conveying the same notion but differing in shades of meaning),

- •Lecture 6 english phraseology

- •1. Phraseological units in English.

- •2. Ways of forming phraseological units.

- •1. Phraseological units in English.

- •2. Ways of forming phraseological units. Their classification.

- •Lecture 7

- •1. The words of informal stylistic layer.

- •Informal Style

- •Colloquial Words

- •Dialect words

- •2. The formal layer of the English vocabulary.

- •Learned Words

- •3. Professionalisms.

- •4. Stylistically neutral layer of the English vocabulary.

- •5. Neologisms in English.

- •Lecture 8 English as the world language. Varieties of English.

- •1. Historical and economic background of widespreading English.

- •2. Some of the distinctive characteristics of american english

- •3. The language of Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

- •4. Some other varieties of English (English of India and Pakistan, African English)

- •2. Historical development of British and American Lexicography.

- •3. Classification of dictionaries

Lecture 1

Lexicology as a linguistic discipline.

Lexicology as a brunch of linguistics. Types of Lexicology.

The connection of lexicology with other linguistic disciplines. Methods of lexicological research.

General problems of the theory of the Word.

1.Lexicology as a brunch of linguistics. Types of Lexicology.

The term „lexicology” is of Greek origin / from „lexis” - „word” and „logos” - „science”/. Lexicology is the part of linguistics which deals with the vocabulary and characteristic features of words and word-groups.

The term „vocabulary” is used to denote the system of words and word-groups that the language possesses.

The term „word” denotes the main lexical unit of a language resulting from the association of a group of sounds with a meaning. This unit is used in grammatical functions characteristic of it. It is the smallest unit of a language which can stand alone as a complete utterance.

The term „word-group” denotes a group of words which exists in the language as a ready-made unit, has the unity of meaning, the unity of syntactical function, e.g. the word-group „as loose as a goose” means „clumsy” and is used in a sentence as a predicative / He is as loose as a goose/.

Lexicology can study the development of the vocabulary, the origin of words and word-groups, their semantic relations and the development of their sound form and meaning. In this case it is called historical lexicology.

Another branch of lexicology is called descriptive and studies the vocabulary at a definite stage of its development.

The main lexical problems:

word structure and formation

semasiology and the semantic classification of words

variants and dialects of ME vocabulary

etymological survey of the E wordstock

ways if enrichment of ME wordstock

The notion of the linguistic sign.

Central

in our representation of the linguistic coding system is the notion

of the linguistic

sign.

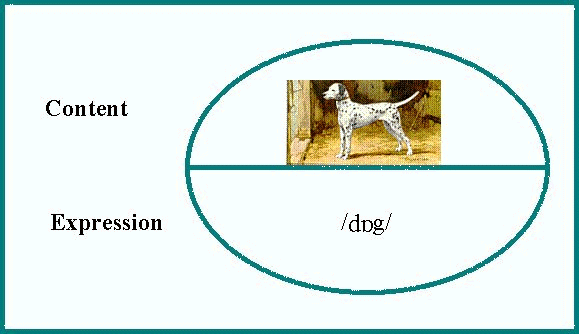

This represents the connection between a content

(meaning) and an expression

(form,

code), e.g. our mental representation of what a dog is (content) and

the word dog

(or ![]() ;

either italics or phonemic transcription will be used to represent

the expression side of the linguistic sign).

;

either italics or phonemic transcription will be used to represent

the expression side of the linguistic sign).

Figure 1. The linguistic sign.

The linguistic sign is conventional in the sense that the speakers of a language must use the same expression to represent the same content (otherwise the receiver's decoding would not recover the content encoded by the sender, and we would not understand each other).

At the same time we can say that the particuar expression we connect with a particular content is in the vast majority of cases arbirary: as long as the members of a speech community agree on what expression to use, it makes no difference exactly what that expression is. Consider, in this connection, the words meaning 'dog' in a few languages: Norwegian bokmål/nynorsk hund, trøndersk dialect hoinn, German Hund, French chien, Czech pes, Russian sobaka, Bulgarian kuche, Swahili mbwa. This principle of the arbitrariness of the linguistic sign is to some extent contradicted by the fact that all languages have words that imitate non-lingustic sounds: the whisper of the wind, the babbling of a brook, the growling of a dog, etc. But note that different languages represent the same non-linguistic sound in different ways, so that we find a certain arbitrariness at work here as well: the crowing of a cock is represented as cock-a-doodle-doo in English, as kykkeliky in Norwegian and as kikeriki in German.

A

simple

linguistic sign

such as

is usually referred to as a morpheme.

It is a unit which cannot be further subdivided (if we consider the

sounds /d/, /![]() /

and /g/ separately, we lose the connection with the content and we

are thus no longer dealing with the morpheme).

/

and /g/ separately, we lose the connection with the content and we

are thus no longer dealing with the morpheme).

A morpheme like is called a free morpheme: it can be used as a word on its own (She saw a dog). A morpheme like -s (meaning 'more than one') is a bound morpheme (more specifically, a suffix), since it must be combined with a free morpheme to form a word (She saw two dogs).