- •Unit 6. Finance for strategy

- •1. Read the text and match the topic sentences a-h to the gaps 1-7.

- •Financial Management functions

- •3. Work with vocabulary. Identify the words and word combinations from the previous exercise by the context provided.

- •4. Lexical Card. Prepare a short talk on the following topics, using the lexical items listed below, either in written or oral form:

- •5. Work either individually or in pairs / groups. Answer the following questions. Prepare a report, if necessary.

- •Text 2 Banking On Blue Chip Stocks

- •1. Scan the text and match the subheadings to the parts I-V.

- •2. Read the text and say whether the statements are true or false.

- •3. Summarize the content of the text.

- •5. Work with vocabulary. Identify the words and word combinations from the previous exercise by the context provided.

- •6. Lexical Card. Prepare a short talk on the following topics, using the lexical items listed below, either in written or oral form:

- •7. Work either individually or in pairs / groups. Answer the following questions. Prepare a report, if necessary.

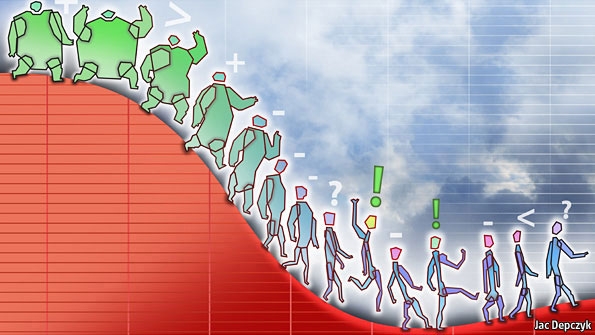

- •Five Steps of a Bubble

- •1. Skim the text and match the pictures a-g to the paragraphs 1-7.

- •§ 3. 1. Displacement

- •§ 4. 2. Boom

- •§ 5. 3. Euphoria

- •§ 6. 4. Profit Taking

- •§ 7. 5. Panic

- •2. Read the text and answer the questions.

- •3. Work with vocabulary. Identify the words and word combinations marked violet in the text with their definitions given in the table below.

- •4. Work with vocabulary. Identify the words and word combinations from the previous exercise by the context provided.

- •5. Lexical Card. Prepare a short talk on the following topics, using the lexical items listed below, either in written or oral form:

- •6. Watch the film “Margin Call” (2011) and describe the situation of the 2008 crisis.

- •7. Work either individually or in pairs / groups. Answer the following questions. Prepare a report, if necessary.

- •1. Scan the text and

- •Five Lessons from the World's Biggest Bankruptcies

- •3. Give the summary of the five lessons from the World's Biggest Bankruptcies.

- •Vocabulary. Part I

- •Vocabulary. Part II

- •5. Work with vocabulary. Identify the words and word combinations from the previous exercise by the context provided.

- •Vocabulary. Part I

- •Vocabulary. Part II

- •6. Lexical Card. Prepare a short talk on the following topics, using the lexical items listed below, either in written or oral form:

- •7. Read the recommended articles in the text and prepare reports on the topics.

- •8. Watch the film “Wall Street II. Money Never Sleeps” (2010) and find illustrations of the processes described in the text.

- •9. Discussion. Lessons to be learnt from the article and the films. Final discussion

- •Unit 6 wordlist

- •Unit 7 Budgets, Decisions and Risks

- •1. Make an outline of the text Managerial Accounting

- •2. Write a word from the box in the correct form in each gap.

- •Money management - an introduction

- •3. Circle the correct word or phrase.

- •4. Develop the topic suggested

- •1 . Highlight the topic sentences and justify your choice Trading on Teamwork

- •Curriculum vitae

- •2. Fill in the gaps with the right prepositions Dealing with debt

- •3. Each of the words or phrases in bold is incorrect. Rewrite them correctly.

- •4. What aspects in the company management should be taken into consideration to make the right investment decision ?

- •1.What is the main idea of the text ? Financial crisis could turn the tide against unrestricted capital flows

- •2. Fill in the right word from the text

- •3. Answer the questions

- •4. Develop the topic: what do the market crises depend on?

- •1. Think of some other title for the text Downturn, start up

- •2. Choose the right word combination (scarce,collateral,teeth, spur,commissioned)

- •3. Qualify the statements, whether they are true or false

- •Unit 8 and 9 People as a Resource / Developing People

- •1. What do you think is similar in the job of a mentor and a coacher? What could be the main difference between them?

- •2. Read the text below to check if your ideas were right. Name the most striking difference between mentoring and coaching. Mentoring versus coaching

- •3. Scan through the text once again and put m next to the phrases which characterize mentoring, and c next to those which are typical of coaching.

- •4. Paraphrase the last sentence of the text. How far do you agree with it?

- •5. Explain the meaning of the highlighted words/phrases in English.

- •6. Translate from Russian into English.

- •7. Discuss in pairs.

- •2. Underline the key phrases which help differentiate one term from the other.

- •3. Define the phrases from the text which are in bold.

- •2A. Scan through the text to check if you were right.

- •2B. Read the text once again and find potential hazards a team can face at some stages.

- •2C. Using your own teamwork experience, name 1) the stage(s) which can be skipped; 2) the other hazards a team can face at each of the stages.

- •1. Scan through the text below and find out why it has got such a title. Team-building for charity brings tears to my eyes

- •2. Answer the following questions about the text:

- •3. Summarize the text ‘Team-building for charity brings tears to my eyes’.

- •4. Define the words in bold.

- •5. Fill in the gaps with an appropriate word / phrase from the box.

- •6. Discuss in pairs.

- •1. The title of the text below is The Value of Poaching. Scan through paragraphs 1-3 and find out what poaching is. Write a short definition for this term.

- •Wordlist for unit 8 and 9

- •Unit 12 Management information systems

- •1. Make an outline of the text.

- •2. Read the definitions and find corresponding words or expressions.

- •3. Think of an appropriate title for the text.

- •4. Explain the difference between data, information and knowledge, providing examples from the sphere of management.

- •1. Make an outline of the text.

- •2. Read the definitions and find corresponding words or expressions.

- •3. Choose the most appropriate title for the text:

- •4. Answer the questions.

- •What information do you need?

- •3. Answer the questions.

- •4. Speak on the role of data, information and knowledge in management studies or business management using one of the following sets of words.

- •2. Read the definitions and find corresponding words or expressions.

- •3. Answer the questions.

- •1. Find the topic sentences of the paragraphs. Management Attitude about cis Resources and Their Use

- •2. Read the definitions and find corresponding words or expressions.

- •3. Match the sentences from the text with the paragraphs 1-9.

- •4. Choose the right alternative.

- •5. Answer the questions.

- •6. Name a few fields where being bullish is vital and being bearish is acceptible; provide supporting arguments.

- •Wordlist for unit 12

2. Fill in the right word from the text

1.The government had to introduce the ---------- --------- measures to help the crisis out.

2.The reasonable capital flow management results in a comfortable return on ----------------.

3.Expertise is just the ----- --- stuff every manager would like to have.

4.Whether you call it a ------------- or a ----------- led to a flood of cash inflow.

5.The recent financial unrest pulled ------ from his business.

3. Answer the questions

1 .What is a contagion risk ?

2 ,What is a fragility risk?

3 .What is a sovereignity risk?

4.What is an emerging economy?

4. Develop the topic: what do the market crises depend on?

TEXT 4

1. Think of some other title for the text Downturn, start up

The effects of recessions on entrepreneurs and managers run deep

Jan 7th 2012 | from the print edition

THE list of famous companies founded during economic downturns is long and varied. It includes General Motors, AT&T, Disney and MTV, all founded during recessions. A 2009 study found that over half of Fortune 500 companies got their start during a downturn or a bear market. A recession, it seems, may not be an entirely bad time to start a company. Indeed, busts (and booms) cast a longer shadow on the business landscape than is commonly realised, because they influence both the rate of business formation and how existing firms are run.

Some argue that recessions speed up the process of productive economic churn—what Joseph Schumpeter called “creative destruction”. The destruction part is easy to see: downturns kill businesses, leaving boarded-up windows on the high street as their gravestones. But recessions may also spur the creation of new businesses.

When people suddenly have less money to spend, clever entrepreneurs may see an opportunity to set up businesses that give them what they want more cheaply or efficiently. Downturns may also swell the ranks of potential firm creators, because many who might otherwise have sought a stable salary will reinvent themselves as entrepreneurs. A recent study by Robert Fairlie of the University of California, Santa Cruz found that the proportion of Americans who start a new business each month is on average about half as high again in metropolitan areas where unemployment is in double digits as in those where it is under 2%.

A recession is a difficult time to start a company, of course. Credit is scarce. Would-be entrepreneurs are further handicapped by falling asset prices, since they might want to use their homes as collateral for a start-up loan. Whether downturns on balance help or hurt entrepreneurs depends therefore on the relative strength of these opposing sets of forces.

Mr Fairlie finds evidence that the spur to enterprise during the most recent recession in America from a drying-up of other employment opportunities outweighed the drag on business formation from a collapsing housing market. That said, a shrinking economy also makes it hard for young firms to take root and grow. A study commissioned by the Kaufmann Foundation, an organisation devoted to entrepreneurs, suggests that young companies, typically responsible for the bulk of US job creation, added only 2.3m jobs in 2009, down from about 3m a year earlier.

Tough times do not suddenly prompt everyone to start a business. The vast majority of people who reach working age during a downturn still look for a job. But research also suggests that recessions have lasting effects on how executives manage businesses. John Graham of Duke University and Krishnamoorthy Narasimhan of PIMCO, a bond manager, have found that chief executives who lived through the Depression tended to run companies with lower debt levels (leverage then went up when these Depression-era bosses retired). In a new study, Antoinette Schoar and Luo Zuo of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology show that companies run many years later by people who cut their teeth during bleak times, when money was tight and customers harder to find, are systematically different from those run by managers whose formative experiences date back to expansionary times, when credit and optimism were in ample supply.

By carefully dissecting the careers of over 5,700 bosses of companies that have been on the S&P 1500 list, Ms Schoar and Mr Zuo found that those who began their management careers during a bust were substantially more risk-averse, took on less debt and generally were more conservative managers than the rest of the sample, even many decades later. That will strike critics of the over-leveraged company as thoroughly good news, but it is hard to say whether this effect is entirely benign.

Bosses whose careers began in a recession also tend to be so concerned about cost-effectiveness that the companies they go on to run spend less on research and development. They may thus be too conservative: firms with bosses whose professional baptism came in a weak economy have lower returns on assets than those run by other managers.

Why should this be? One plausible explanation is that recessions affect the way people take decisions. Management styles are surely in part the result of the kinds of problems a person has had to grapple with. Even a risk-lover may end up taking more conservative financial decisions in a weak economy. If these decisions serve him well in lean times, then he may conclude that fiscal prudence is a stance worth sticking with in years of plenty.

Recessionary genes

Downturns also funnel people into different jobs from those they might otherwise have entered. A 2008 study by Paul Oyer of Stanford University found that Stanford MBAs disproportionately shunned Wall Street during a bear market. This may seem unsurprising—who wants a job in finance when the market is tanking? But there are reasons to believe that these choices make a difference well into the future. Those who begin their careers in a bust are less footloose than their boom-time equivalents. Ms Schoar and Mr Zuo find that the average recession-scarred chief executive is more likely to have risen through the ranks of a firm than the norm, and is less likely to have switched employers or jumped from one industry to another.

The pool of candidates for top jobs in a particular industry reflects the choices that people make early on in their working lives. Yet these choices are the result not only of managers’ preferences and abilities, as you might expect, but also of the economic circumstances that prevailed at the time they began working. Whether they were set up during a boom or a bust, today’s firms are deeply affected by the economic fluctuations of the past.

Sources

1. “Shaped by Booms and Busts: How the Economy Impacts CEO Careers and Management Style” by Antoinette Schoar and Luo Zuo. // NBER Working Paper No. 1759, November 2011.

http://www.nber.org/papers/w17590

2. “Entrepreneurship, Economic Conditions and the Great Recession”, by Robert W. Fairlie. IZA Discussion Paper No. 5725, May 2011.

http://ftp.iza.org/dp5725.pdf

3. “The Making of an Investment Banker: Macroeconomic Shocks, Career Choice, and Lifetime Income”, by Paul Oyer. NBER Working Paper No. 12059, February 2006.

http://www.nber.org/papers/w12059

URL:http://www.economist.com/node/21542390