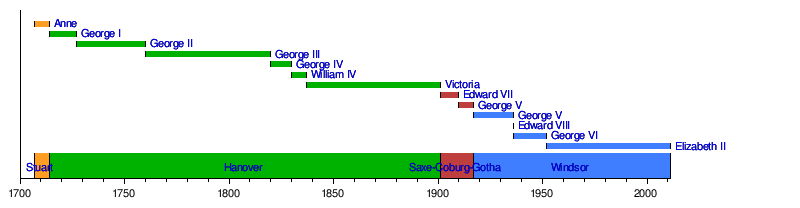

- •The timeline of British Monarchs during last 3 centuries

- •Answer the following questions using the text.

- •Match word combinations with their Russian equivalents:

- •Fill in the prepositions.

- •Translate the following sentences into English making use of words from the text.

- •Translate into English using Comparative and Superlative forms:

- •Fill the table with Comparative and Superlative forms of adjectives:

- •What tenses can one use speaking about the past? What tenses are used in the text?

- •Match the words from the text with their synonyms in the second list.

- •Give the list of fish species/animals mentioned in the text. Can you add more names?

- •Give the list of colors mentioned in the text. Add as many colors as possible. Speak about gradations. You can make it a team play.

- •Which facts given by Venerable Bede seem unreal? Why? Discuss in a group.

- •Search through the text for English equivalents to the following phrases:

PAGES OF HISTORY

Warm up

1. Answer the following questions. Work in a group. Compare your answers.

- What do you know about history of England? Do you remember any bright characters or events from it?

- Can you describe the relationships between Great Britain and Russia in their historical dimension? Were there any periods of common challenges or mutual influence?

- Are there any facts about English history you would like to know better?

- What American presidents do you know? What are they famous for?

- What period of American history seems you most interesting? Why?

2. Offer and choose subtopics for the presentation (individual or in a group).

Here are some ideas:

- What do we know about Celtic culture? Can we see any elements of it in modern life?

- What was the role of the roman invasion in Britain?

- When did the Christianity come to Britain? What did it bring to the local culture?

- Who was Henry VIII? Can one man change the way of the whole country?

- Personalities (Elisabeth I; Charles I; W.Churchill; M.Thatcher etc.)

- Urban life in the USA today. What are the issues?

- History of American cities (Boston, New York, Chicago etc.).

Choose the way you are going to do a presentation at the end of the unit.

GREAT BRITAIN

Reading

What Do the British Know About Their Own History?

In order to understand the people of another country, you may not need to study their history in detail, but you need to know about their own idea of their past. (…)

The British (apart from those in Northern Ireland) live in a country which has not been invaded for 900 years. Monuments of our past cover our countryside: bronze age burial mounds, Roman walls, churches from the tenth century onwards, castles, palaces and simple country homes are all part of a landscape we take for granted. Because much of building was in stone or brick it has survived better than the predominantly wooden buildings in Russia. (…)

How much do most of us know of our history? “Rather less than can be written on the back of a postage stamp,” said one friend tartly. History teaching in our schools has never been ideological in the Soviet sense, although unspoken ideologies have shaped the story told to children; and in recent years there has been much discussion of what kind of history should be taught. I was expected to know a basic “chronology of events”, such matters as “reasons for the Civil War” and, later, an analysis of our relationships with other countries. My older children concentrated on economic and social history: they learnt about how we lived in different centuries, they studied the growth of industry and transport, they examined medical facilities in Victorian times. My younger children were taught that “history” was always the interpretation of evidence, and that therefore they must examine the evidence. So they investigated archaeological sites, studied census statistics and read conflicting reports of notable events in order to appreciate that the truth can never be fully known. Unfortunately, this taught them to be skeptical without an adequate basis of knowledge, i.e. of facts that need to be known before we can criticize them for being inadequate.

History teachers are constantly involved in such methodological discussion, and somehow from between the cracks in their debates emerges a “story of Britain” which is crude, simple and not very accurate, but which goes something like this:

After the stone age, bronze age, iron age, Romans, Saxons and Danes, England became England. William the Conqueror invaded England from France in 1066 (this is the date that everybody knows), killed King Harold and became Our King (1). In the Middle Ages we built beautiful churches, started limiting the power of the King, died in millions of the Black Death (2) and beat the French at Agincourt (though we forget that the French won the war). In the sixteenth century we had Henry VШ with his six wives. He abolished the Pope as the head of the Church in England and made himself Head instead. (This was a popular move.) Under Queen Elisabeth we fought and beat the Spanish (3); under James I we captured Guy Fawkes just before he attempted to blow up the Houses of Parliament, an event which the English population celebrates every year on the fifth of November with big fires and effigies of Guy Fawkes. Under Charles we had a Civil war, executed the king (4), had a Republic briefly under Cromwell (5) and in 1660 restored the monarchy – on conditions. Power passed into the hands of Parliament and was – more or less – enshrined in law. In the eighteenth century we invented new scientific, agricultural and industrial processes, such as the steam engine. Then we beat Napoleon (6). During the nineteenth century we extended our Empire even further, produced learned men like Darwin (7), refined our sophisticated Parliament, increased Britain’s riches and went into battle in 1914 with all banners flying… Or did we? At this point the triumphant story falters. Many of the conscripts in the First World War had to be rejected for malnourishment and ill-health. The consequences of industrialization had been horrific (and in any case America and Germany were beating us). Yes, we won the war, but the soldiers returned to unemployment and even hunger. Some people, anxious that the poor at last would have wrights, hoped for a revolution such as had happened in the Russian Empire. The colonized peoples of our Empire were growing restive too. But Britain, unlike Germany, was never poised on the edge of revolution. Despite a General Strike (8) and a recession, many parts of the country were getting more prosperous. Between the wars, millions of people moved for the first time into decent housing, and electricity, roads and other public services became widely available. Our politicians wondered whether to fight Hitler. The people seem to have known that war was inevitable and that it would be grim and necessary.

Like you we have our national myths of the Second World War and every Christmas new books are published on the subject and old films re-shown. In Britain far fewer people were killed than in the First World War (about a quarter of a million, of whom some tens of thousands were civilian victims of bombing (9)). (…) In this country every able-bodied adult was conscripted; women were sent to do war-work; gardens were turned over to vegetables and spare pieces of land were cultivated. We needed food. Although never invaded, we suffered considerable bomb damage, and many people, especially children, were evacuated to safer parts of the country. Everybody was affected.(…)

After the war, the world position of Britain altered. Our Empire collapsed around us – and we conceded that we no longer had the right to rule other countries. We joined NATO and became part of the “American sphere of influence”. (…)

This version of our history in which triumph gives way to doubt and debate in the contemporary world has been questioned by some of our politicians. Should these doubts be voiced to children? Or should history be used as propaganda – for example to give children a new pride in Britain – which would mean being very selective about the facts. Mrs Thatcher was sure it should be so used; teachers, however, want freedom from propaganda. But can they get it? Should our lessons be more international, incorporating the stories of the West Indian and Asian communities living here? Or is the story of the English Civil War important for everyone, black and white?

Meanwhile, ordinary people here are exploring their “heritage” with immense enthusiasm. Groups of amateur historians write the history of their town or village; excellent programs are made for television and new museums open almost daily. Partly the enthusiasm is no more than a sentimental dream of the past, all stately homes and romantic aristocrats. But much of the passion is more significant. Although we have not been cut off the past by a colossal fracture in our history (as have the Germans and the Soviet people, for example) we nonetheless find it difficult to relate our contemporary experience to what has gone before. So people watch the TV programmes, read the books, study the documents, dig up the ancient cities, and wander round the museums asking themselves (…): Who are the British and how they come out of the past into today?

(from “Understanding Britain” by K. Hewitt)

Notes:

On the name of the country:

England got its name in the early period of its history when its territory was invaded by Anglo-Saxon German tribes. When Elizabeth died in 1603, King of Scotts James VI became King James I of England in a Union of the Crowns. King James I & VI as he was styled became the first monarch to rule the entire island of Great Britain, although it was merely a union of the English and Scottish crowns, and both countries remained separate political entities until 1707. The Acts of Union between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland were a pair of Parliamentary Acts passed by both parliaments in 1707, which dissolved them in order to form a Kingdom of Great Britain governed by a unified Parliament. The Acts joined two kingdoms into a single one.

The Anglo-Irish treaty of 1921 established the Irish Free State (now the Republic of Ireland) as a separate state, leaving Northern Ireland as part of the United Kingdom. The official name of the UK thus became "The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland".

After Wessex dynasty with a short period of Danish kings William the Conqueror starts Norman Royal dynasty and the tradition to give numbers to Kings and Queens.

For memorizing the order of English Royal Houses after William one can use mnemonics like

“No Plan Like Yours To Study History Wisely”

which means: dynasty (famous person from it)

England Norman (William the Conqueror)

Plantagenet (Richard the Lionheart)

Lancaster

York (Richard III (described by Shakespeare))

Tudor (Henry VIII, Elisabeth I)

Great Britain Stuart (James I, Charles I)

Hanover (Victoria)

Windsor (Elisabeth II, since 1952)

The timeline of British Monarchs during last 3 centuries

2. The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history in Europe between 1348 and 1350.

3. When Spain tried to invade and conquer England it was a fiasco, and the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 associated Elizabeth's name forever with what is popularly viewed as one of the greatest victories in English history.

4. The capture and subsequent trial of Charles led to his beheading in January 1649 at Whitehall Gate in London, making England a republic. The trial and execution of Charles by his own subjects shocked the rest of Europe (the king argued to the end that only God could judge him) and was a precursor of sorts to the beheading of Louis XVI 145 years later.

5. The New Model Army, under the command of Oliver Cromwell, then scored decisive victories against Royalist armies in Ireland and Scotland. Cromwell was given the title Lord Protector in 1653, making him 'king in all but name' to his critics.

6. The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815 near Waterloo in present-day Belgium. Imperial French army under the command of Emperor Napoleon was defeated by combined armies of the Seventh Coalition, an Anglo-Allied army under the command of the Duke of Wellington combined with a Prussian army under the command of Gebhard von Blucher. It was the culminating battle of the Waterloo Campain and Napoleon's last. The defeat at Waterloo put an end to Napoleon's rule as Emperor of the French and marked the end of his Hundred Days' return from exile.

7. Charles Robert Darwin (1809 – 1882) was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection. He published his theory with compelling evidence for evolution in his 1859 book “On the Origin of Species”.

8. The 1926 general strike in the United Kingdom lasted nine days, from 4 May 1926 to 13 May 1926. It was called by the general council of the Trade Union Congress) in an unsuccessful attempt to force the British Government to act to prevent wage reduction and worsening conditions for coal miners.

9. The Blitz (from German, "lightning") was the sustained strategic bombing of Britain by Nazi Germany between 7 September 1940 and 10 May 1941, during the Second World War. The city of London was bombed by the Luftwaffe for 76 consecutive nights and many towns and cities across the country followed. More than one million London houses were destroyed or damaged, and more than 40,000 civilians were killed, half of them in London.

Active vocabulary

Invade (v) – вторгаться, захватывать, оккупировать; invasion (v) – вторжение, нашествие;

Shape (v) – придавать форму, моделировать, формировать; shape (n) - форма, очертание, вид (in bad shape, in any shape); to take the shape of smth – принимать форму чего-либо;

Evidence (n) – 1.очевидность, наглядность, ясность; 2. факты, доказательства, экспериментальные данные, довод (direct, empirical, statistical, strong evidence), свидетельство, улика, симптом, признак;

Adequate (adj) – соответствующий (definition adequate to the expectations); достаточный (it would be adequate to list just the basic rules); компетентный, отвечающий требованиям, пригодный (для какой-либо деятельности) (He was adequate to the task); ant. inadequate;

Crude (adj) – сырой (crude oil), необработанный (crude stone), незрелый (crude fruit), непродуманный (crude plan), черновой (crude text);

Abolish (v) – аннулировать, упразднять, отменять;

Falter (v) – действовать нерешительно, спотыкаться, ковылять, мямлить, заикаться;

Consequences (of) (n, pl) – последствия; far-reaching, logical, tragic, inevitable consequences – далеко идущие, логические, трагические, неизбежные последствия: to take the consequences of – отвечать за последствия; consequently (adv) - впоследствии;

Perception (of) (n) – восприятие, ощущение, осознание (visual perception).

Sophisticated (adj) – 1.утонченный, изысканный (music, wine): опытный, искушенный (craftsman), сложный, изощренный (plot, plan).

Pay attention to the ready structures like:

their own idea of the past

take for granted

all banners flying

poised on the edge of

suffer considerable bomb damage

civilian victims of bombing

colossal fracture in our history

dig up the ancient cities

be enshrined in law

amateur historian

common ancestry

Reading comprehension