- •Global Strategy at General Motors

- •Introduction

- •Strategy and the Firm

- •Support Activities

- •The Role of Strategy

- •Profiting from Global Expansion

- •Transferring Core Competencies

- •Realizing Location Economies

- •Creating a Global Web

- •Some Caveats

- •Realizing Experience Curve Economies

- •Learning Effects

- •Strategic Significance

- •Pressures for Cost Reductions and Local Responsiveness

- •Figure 12.3

- •Pressures for Cost Reductions

- •Differences in Infrastructure and Traditional Practices

- •Differences in Distribution Channels

- •Host Government Demands

- •Implications

- •Strategic Choice

- •International Strategy

- •Figure 12.4

- •Multidomestic Strategy

- •Global Strategy

- •Transnational Strategy

- •Summary

- •Figure 12.6

- •Case Discussion Questions

Transnational Strategy

Christopher Bartlett and Sumantra Ghoshal have argued that in today's environment, competitive conditions are so intense that to survive in the global marketplace, firms must exploit experience-based cost economies and location economies, they must transfer core competencies within the firm, and they must do all this while paying attention to pressures for local responsiveness.20 They note that in the modern multinational enterprise, core competencies do not reside just in the home country. They can develop in any of the firm's worldwide operations. Thus, they maintain that the flow of skills and product offerings should not be all one way, from home firm to foreign subsidiary, as in the case of firms pursuing an international strategy. Rather, the flow should also be from foreign subsidiary to home country, and from foreign subsidiary to foreign subsidiary--a process they refer to asglobal learning (for examples of such knowledge flows, see the opening case on General Motors and the Management Focus on McDonald's). Bartlett and Ghoshal refer to the strategy pursued by firms that are trying to achieve all these objectives simultaneously as a transnational strategy.

A transnational strategy makes sense when a firm faces high pressures for cost reductions and high pressures for local responsiveness. Firms that pursue a transnational strategy are trying to simultaneously achieve low-cost and differentiation advantages. As attractive as this sounds, the strategy is not an easy one to pursue. Pressures for local responsiveness and cost reductions place conflicting demands on a firm. Being locally responsive raises costs, which makes cost reductions difficult to achieve. How can a firm effectively pursue a transnational strategy?

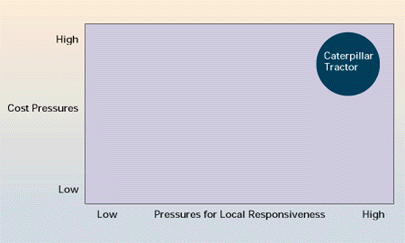

Some clues can be derived from Caterpillar Inc. In the late 1970s, the need to compete with low-cost competitors such as Komatsu and Hitachi of Japan forced Caterpillar to look for greater cost economies. At the same time, national variations in construction practices and government regulations meant that Caterpillar had to remain responsive to local demands. As illustrated in Figure 12.5, Caterpillar was confronted with significant pressures for cost reductions and for local responsiveness.

To deal with cost pressures, Caterpillar redesigned its products to use many identical components and invested in a few large-scale component manufacturing facilities, sited at favorable locations, to fill global demand and realize scale economics. The firm augmented the centralized manufacturing of components with assembly plants in each of its major global markets. At these plants, Caterpillar added local product features, tailoring the finished product to local needs. By pursuing this strategy, Caterpillar realized many of the benefits of global manufacturing while responding to pressures for local responsiveness by differentiating its product among national markets.21 Caterpillar started to pursue this strategy in 1979 and by 1997 had doubled output per employee, significantly reducing its overall cost structure. Meanwhile, Komatsu and Hitachi, which are still wedded to a Japan-centric global strategy, have seen their cost advantages evaporate and have been steadily losing market share to Caterpillar. (General Motors is trying to pursue a similar strategy with its development of common global platforms for some of its vehicles; see the opening case for details.) Figure 12.5

Cost Pressures and Pressures for Local Responsiveness Facing Caterpillar

For another example consider Unilever. Once a classic multidomestic firm, Unilever has had to shift toward more of a transnational strategy. A rise in low-cost competition, which increased cost pressures, has forced Unilever to look for ways of rationalizing its detergents business. During the 1980s, Unilever had 17 different and largely self-contained detergents operations in Europe alone. The duplication in assets and marketing was enormous. Also, because Unilever was so fragmented it could take as long as four years for the firm to introduce a new product across Europe. Now Unilever is trying to weld its European operation into a single entity, with detergents being manufactured in a handful of cost-efficient plants, and standard packaging and advertising being used across Europe. According to company estimates, the result could be an annual cost saving of over $200 million. At the same time, however, due to national differences in distribution channels and brand awareness, Unilever recognizes that it must still remain locally responsive, even while it tries to realize economies from consolidating production and marketing at the optimal locations.22

Bartlett and Ghoshal admit that building an organization that can support a transnational strategic posture is complex and difficult. Simultaneously trying to achieve cost efficiencies, global learning, and local responsiveness places contradictory demands on an organization. Chapter 13 discusses how a firm can deal with the dilemmas posed by such difficult organizational issues. Firms that attempt to pursue a transnational strategy can become bogged down in an organizational morass that only leads to inefficiencies.

Bartlett and Ghoshal may be overstating the case for the transnational strategy when they present it as the only viable strategy. While no one doubts that in some industries the firm that can adopt a transnational strategy will have a competitive advantage, but in other industries, global, multidomestic, and international strategies remain viable. In the semiconductor industry, for example, pressures for local customization are minimal and competition is purely a cost game, in which case a global strategy, not a transnational strategy, is optimal. This is the case in many industrial goods markets where the product serves universal needs. But the argument can be made that to compete in certain consumer goods markets, such as the automobile and consumer electronics industry, a firm has to try to adopt a transnational strategy.