- •Deutsche Telekom Taps the Global Capital Market

- •Introduction

- •Figure 11.1

- •The Investor's Perspective: Portfolio Diversification

- •Information Technology

- •Deregulation

- •Figure 11.7

- •Global Capital Market Risks

- •The Eurocurrency Market

- •Genesis and Growth of the Market

- •Attractions of the Eurocurrency Market

- •Figure 11.8

- •Interest Rate Spreads in Domestic and Eurocurrency Markets

- •Drawbacks of the Eurocurrency Market

- •The Global Bond Market

- •Favorable Tax Status

- •The Global Equity Market

- •Foreign Exchange Risk and the Cost of Capital

- •Implications for Business

- •Case Discussion Questions

Attractions of the Eurocurrency Market

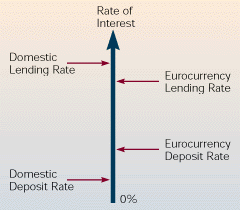

The main factor that makes the eurocurrency market so attractive to both depositors and borrowers is its lack of government regulation. This allows banks to offer higher interest rates on eurocurrency deposits than on deposits made in the home currency, making eurocurrency deposits attractive to those who have cash to deposit. The lack of regulation also allows banks to charge borrowers a lower interest rate for eurocurrency borrowings than for borrowings in the home currency, making eurocurrency loans attractive for those who want to borrow money. In other words, the spread between the eurocurrency deposit rate and the eurocurrency lending rate is less than the spread between the domestic deposit and lending rates (see Figure 11.8). To understand why this is so, we must examine how government regulations raise the costs of domestic banking.

Domestic currency deposits are regulated in all industrialized

Figure 11.8

Interest Rate Spreads in Domestic and Eurocurrency Markets

branches of US banks subject to US reserve requirement regulations, provided those deposits are payable only outside the United States. This gives eurobanks a competitive advantage.

For example, suppose a bank based in New York faces a 10 percent reserve requirement. According to this requirement, if the bank receives a $100 deposit, it can lend out no more than $90 of that and it must place the remaining $10 in a non-interest-bearing account at a Federal Reserve bank. Suppose the bank has annual operating costs of $1 per $100 of deposits and that it charges 10 percent interest on loans. The highest interest the New York bank can offer its depositors and still cover its costs is 8 percent per year. Thus, the bank pays the owner of the $100 deposit (0.08 * $100 =) $8, earns (0.10 * $90 =) $9 on the fraction of the deposit it is allowed to lend, and just covers its operating costs.

In contrast, a eurobank can offer a higher interest rate on dollar deposits and still cover its costs. The eurobank, with no reserve requirements regarding dollar deposits, can lend out all of a $100 deposit. Therefore, it can earn 0.10 * $100 = $10 at a loan rate of 10 percent. If the eurobank has the same operating costs as the New York bank ($1 per $100 deposit), it can pay its depositors an interest rate of 9 percent, a full percentage point higher than that paid by the New York bank, and still cover its costs. That is, it can pay out 0.09 * $100 = $9 to its depositor, receive $10 from the borrower, and be left with $1 to cover operating costs. Alternatively, the eurobank might pay the depositor 8.5 percent (which is still above the rate paid by the New York bank), charge borrowers 9.5 percent (still less than the New York bank charges), and cover its operating costs even better. Thus, the eurobank has a competitive advantage vis-à-vis the New York bank in both its deposit rate and its loan rate.

Clearly, there are very strong financial motivations for companies to use the eurocurrency market. By doing so, they receive a higher interest rate on deposits and pay less for loans. Given this, the surprising thing is not that the euromarket has grown rapidly but that it hasn't grown even faster. Why do any depositors hold deposits in their home currency when they could get better yields in the eurocurrency market?