- •Deutsche Telekom Taps the Global Capital Market

- •Introduction

- •Figure 11.1

- •The Investor's Perspective: Portfolio Diversification

- •Information Technology

- •Deregulation

- •Figure 11.7

- •Global Capital Market Risks

- •The Eurocurrency Market

- •Genesis and Growth of the Market

- •Attractions of the Eurocurrency Market

- •Figure 11.8

- •Interest Rate Spreads in Domestic and Eurocurrency Markets

- •Drawbacks of the Eurocurrency Market

- •The Global Bond Market

- •Favorable Tax Status

- •The Global Equity Market

- •Foreign Exchange Risk and the Cost of Capital

- •Implications for Business

- •Case Discussion Questions

Information Technology

Financial services is an information-intensive industry. It draws on large volumes of information about markets, risks, exchange rates, interest rates, creditworthiness, and so on. It uses this information to make decisions about what to invest where, how much to charge borrowers, how much interest to pay to depositors, and the value and riskiness of a range of financial assets including corporate bonds, stocks, government securities, and currencies.

Because of this information intensity, the financial services industry has been revolutionized more than any other industry by advances in information technology since the 1970s. The growth of international communications technology has facilitated instantaneous communication between any two points on the globe. At the same time, rapid advances in data processing capabilities have allowed market makers to

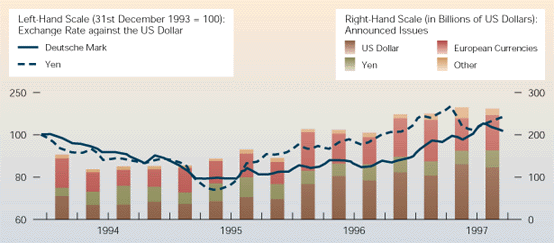

Figure 11.5

International Bond Issues and the US Dollar Exchange Rate.

Source: Bank for International Settlements database; Euromoney data; Bank of England data.

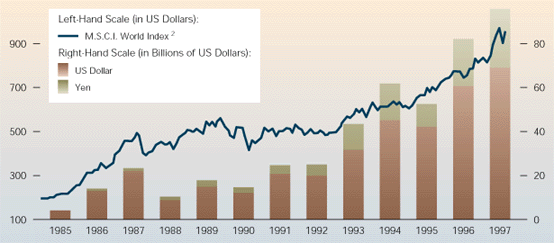

Figure 11.6

International Equity Offerings and Equity Price Developments

Source: Bank for International Settlements database; Euromoney data.

absorb and process large volumes of information from around the world. According to one study, because of these technological developments, the real cost of recording, transmitting, and processing information has fallen by 95 percent since 1964.10

Such developments have facilitated the emergence of an integrated international capital market. It is now technologically possible for financial services companies to engage in 24-hour-a-day trading, whether it is in stocks, bonds, foreign exchange, or any other financial asset. Due to advances in communications and data processing technology, the international capital market never sleeps. San Francisco closes one hour before Tokyo opens, but during this period trading continues in New Zealand.

The integration facilitated by technology has a dark side.11 "Shocks" that occur in one financial center now spread around the globe very quickly. The collapse of US stock prices on the notorious Black Monday of October 19, 1987, immediately triggered similar collapses in all the world's major stock markets, wiping billions of dollars off the value of corporate stocks worldwide. However, most market participants would argue that the benefits of an integrated global capital market far outweigh any potential costs.

Deregulation

In country after country, financial services have been the most tightly regulated of all industries. Governments around the world have traditionally kept other countries' financial service firms from entering their capital markets. In some cases, they have also restricted the overseas expansion of their domestic financial services firms. In many countries, the law has also segmented the domestic financial services industry. In the United States, for example, commercial banks are prohibited from performing the functions of investment banks, and vice versa. Historically, many countries have limited the ability of foreign investors to purchase significant equity positions in domestic companies. They have also limited the amount of foreign investment that their citizens could undertake. In the 1970s, for example, capital controls made it very difficult for a British investor to purchase American stocks and bonds.

Many of these restrictions have been crumbling since the late 1970s. In part, this has been a response to the development of the Eurocurrency market, which from the beginning was outside of national control. (This is explained later in the chapter.) It has also been a response to pressure from financial services companies, which have long wanted to operate in a less regulated environment. Increasing acceptance of the free market ideology associated with an individualistic political philosophy also has a lot to do with the global trend toward the deregulation of financial markets (see Chapter 2). Whatever the reason, deregulation in a number of key countries has undoubtedly facilitated the growth of the international capital market.

The trend began in the United States in the late 1970s and early 80s with a series of changes that allowed foreign banks to enter the US capital market and domestic banks to expand their operations overseas. In Great Britain, the so-called Big Bang of October 1986 removed barriers that had existed between banks and stockbrokers and allowed foreign financial service companies to enter the British stock market. Restrictions on the entry of foreign securities houses have been relaxed in Japan, and Japanese banks are now allowed to open international banking facilities. In France, the "Little Bang" of 1987 is gradually opening the French stock market to outsiders and to foreign and domestic banks. In Germany, foreign banks are now allowed to lend and manage foreign deutsche mark issues, subject to reciprocity agreements.12 All of this has enabled financial services companies to transform themselves from primarily domestic companies into global operations with major offices around the world--a prerequisite for the development of a truly international capital market. As we saw in Chapter 5, in late 1997, the World Trade Organization brokered a deal that removed many of the restrictions on cross-border trade in financial services. This deal should encourage further growth in the size of the global capital market.

In addition to the deregulation of the financial services industry, many countries beginning in the 1970s started to dismantle capital controls, loosening both restrictions on inward investment by foreigners and outward investment by their own citizens and corporations. By the 1980s, this trend spread from developed nations to the emerging economies of the world as countries across Latin America, Asia, and Eastern Europe started to dismantle decades-old restrictions on capital flows. Figure 11.7 illustrates the consequences. Since 1985, an index of capital controls in emerging markets that is com