- •Deutsche Telekom Taps the Global Capital Market

- •Introduction

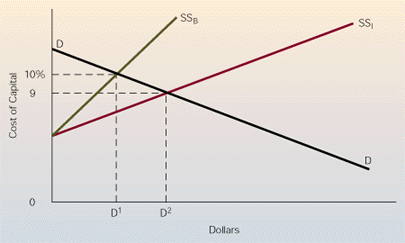

- •Figure 11.1

- •The Investor's Perspective: Portfolio Diversification

- •Information Technology

- •Deregulation

- •Figure 11.7

- •Global Capital Market Risks

- •The Eurocurrency Market

- •Genesis and Growth of the Market

- •Attractions of the Eurocurrency Market

- •Figure 11.8

- •Interest Rate Spreads in Domestic and Eurocurrency Markets

- •Drawbacks of the Eurocurrency Market

- •The Global Bond Market

- •Favorable Tax Status

- •The Global Equity Market

- •Foreign Exchange Risk and the Cost of Capital

- •Implications for Business

- •Case Discussion Questions

Figure 11.1

The Main Players in a Generic Capital Market

borrowers together and charge commissions for doing so. For example, Merrill Lynch may act as a stockbroker for an individual who wants to invest some money. Its personnel will advise her as to the most attractive purchases and buy stock on her behalf, charging a fee for the service.

Capital market loans to corporations are either equity loans or debt loans. An equity loan is made when a corporation sells stock to investors. The money the corporation receives in return for its stock can be used to purchase plants and equipment, fund R&D projects, pay wages, and so on. A share of stock gives its holder a claim to a firm's profit stream. The corporation honors this claim by paying dividends to the stockholders. The amount of the dividends is not fixed in advance. Rather, it is determined by management based on how much profit the corporation is making. Investors purchase stock both for their dividend yield and in anticipation of gains in the price of the stock. Stock prices increase when a corporation is projected to have greater earnings in the future, which increases the probability that it will raise future dividend payments.

A debt loan requires the corporation to repay a predetermined portion of the loan amount (the sum of the principal plus the specified interest) at regular intervals regardless of how much profit it is making. Management has no discretion as to the amount it will pay investors. Debt loans include cash loans from banks and funds raised from the sale of corporate bonds to investors. When an investor purchases a corporate bond, he purchases the right to receive a specified fixed stream of income from the corporation for a specified number of years (i.e., until the bond maturity date).

Attractions of the Global Capital Market

Why do we need a global capital market? Why are domestic capital markets not sufficient? A global capital market benefits both borrowers and investors. It benefits borrowers by increasing the supply of funds available for borrowing and by lowering the cost of capital. It benefits investors by providing a wider range of investment opportunities, thereby allowing them to build portfolios of international investments that diversify their risks.

The Borrower's Perspective: A Lower Cost of Capital

In a purely domestic capital market, the pool of investors is limited to residents of the country. This places an upper limit on the supply of funds available to borrowers. In other words, the liquidity of the market is limited. (Deutsche Telekom faced this problem in the opening case.) A global capital market, with its much larger pool of investors, provides a larger supply of funds for borrowers to draw on.

Perhaps the most important drawback of the limited liquidity of a purely domestic capital market is that the cost of capital tends to be higher than it is in an international market. The cost of capital is the rate of return that borrowers must pay investors (the price of borrowing money). This is the interest rate on debt loans and the dividend yield and expected capital gains on equity loans. In a purely domestic market, the limited pool of investors implies that borrowers must pay more to persuade investors to lend them their money. The larger pool of investors in an international market implies that borrowers will be able to pay less. Figure 11.2

Market Liquidity and the Cost of Capital

The argument is illustrated in Figure 11.2, using the Deutsche Telekom example. The vertical axis in the figure is the cost of capital (the price of borrowing money) and the horizontal axis, the amount of money available at varying interest rates. DD is the Deutsche Telekom demand curve for borrowings. Note that the Deutsche Telekom demand for funds varies with the cost of capital; the lower the cost of capital, the more money Deutsche Telekom will borrow. (Money is just like anything else; the lower its price, the more of it people can afford.) SSB is the supply curve of funds available in the German capital market, and SSI represents the funds available in the global capital market. Note that Deutsche Telekom can borrow more funds more cheaply on the global capital market. As Figure 11.2 illustrates, the greater pool of resources in the global capital market both lowers the cost of capital and increases the amount Deutsche Telekom can borrow. Thus, the advantage of a global capital market to borrowers is that it lowers the cost of capital.

Problems of limited liquidity are not restricted to less developed nations, which naturally tend to have smaller domestic capital markets. As illustrated in the opening case and discussed in the introduction, in recent years even very large enterprises based in some of the world's most advanced industrialized nations have tapped the international capital markets in their search for greater liquidity and a lower cost of capital.4 Another example of a company that tapped the global capital market to lower its cost of capital is profiled in the accompanying Management Focus.