- •Introduction

- •Implications for Business

- •The Tragedy of the Congo (Zaire)

- •Introduction

- •The Gold Standard

- •Nature of the Gold Standard

- •The Strength of the Gold Standard

- •The Period between the Wars, 1918-1939

- •The Bretton Woods System

- •Flexibility

- •The Role of the World Bank

- •The Collapse of the Fixed Exchange Rate System

- •Exchange Rates since 1973

- •Figure 10.1

- •Speculation

- •Uncertainty

- •Who Is Right?

- •Exchange Rate Regimes in Practice

- •Pegged Exchange Rates and Currency Boards

- •Figure 10.2

- •Target Zones: The European Monetary System

- •Performance of the System

- •Recent Activities and the Future of the imf

- •Financial Crises in the Post-Bretton Woods Era

- •Third World Debt Crisis

- •Figure 10.3

- •Mexican Currency Crisis of 1995

- •The Asian Crisis

- •The Investment Boom

- •Excess Capacity

- •The Debt Bomb

- •Expanding Imports

- •The Crisis

- •Evaluating the imf's Policy Prescriptions

- •Implications for Business

- •Currency Management

- •Business Strategy

- •Corporate - Government Relations

- •Chapter Summary

- •Critical Discussion Questions

- •Case Discussion Questions

Third World Debt Crisis

The Third World debt crisis had its roots in the OPEC oil price hikes of 1973 and 1979. These resulted in massive flows of funds from the major oil-importing nations (Germany, Japan, and the United States) to the oil-producing nations of OPEC. Commercial banks stepped in to recycle this money, borrowing from OPEC countries and lending to governments and businesses around the world. Much of the recycled money ended up in the form of loans to the governments of various Latin American and African nations. The loans were made on the basis of optimistic assessments about these nations' growth prospects, which did not materialize. Instead, Third World economic growth was choked off in the early 1980s by a combination of factors, including high inflation, rising short-term interest rates (which increased the costs of servicing the debt), and recession conditions in many industrialized nations (which were the markets for Third World goods).

The consequence was a Third World debt crisis of huge proportions. At one point it was calculated that commercial banks had over $1 trillion of bad debts on their books, debts that the debtor nations had no hope of paying off. Against this background, Mexico announced in 1982 that it could no longer service its $80 billion in international debt without an immediate new loan of $3 billion. Brazil quickly followed, revealing it could not meet the required payments on its borrowed $87 billion.

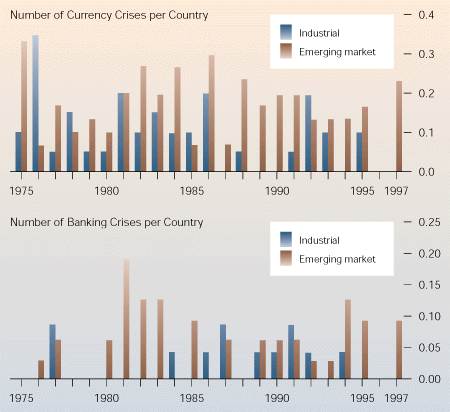

Figure 10.3

Incidence of Currency and Banking Crises, 1975 - 1997

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, 1998 (Washington, DC: IMF, May 1998), p. 77.

Then Argentina and several dozen other countries of lesser credit standings followed suit. The international monetary system faced a crisis of enormous dimensions.

Into the breach stepped the IMF. Together with several Western governments, particularly that of the United States, the IMF emerged as the key player in resolving the debt crisis. The deal with Mexico involved three elements: (1) rescheduling of Mexico's old debt, (2) new loans to Mexico from the IMF, the World Bank, and commercial banks, and (3) the Mexican government's agreement to abide by a set of IMF-dictated macroeconomic prescriptions for its economy, including tight control over the growth of the money supply and major cuts in government spending.

However, the IMF's solution to the debt crisis contained a major weakness: It depended on the rapid resumption of growth in the debtor nations. If this occurred, their capacity to repay debt would grow faster than their debt itself, and the crisis would be resolved. By the mid-1980s, it was clear this was not going to happen. The IMF-imposed macroeconomic policies did bring the trade deficits and inflation rates of many debtor nations under control, but it created sharp contractions in their economic growth rates.

It was apparent by 1989 that the debt problem was not going to be solved merely by rescheduling debt. In April of that year, the IMF endorsed a new approach that had been proposed by Nicholas Brady, the US Treasury secretary. The Brady Plan, as it became known, stated that debt reduction, as distinguished from debt rescheduling, was a necessary part of the solution and the IMF and World Bank would assume roles in financing it. The essence of the plan was that the IMF, the World Bank, and the Japanese government would each contribute $10 billion toward debt reduction. To gain access to these funds, a debtor nation would once again have to submit to imposed conditions for macroeconomic policy management and debt repayment. The first application of the Brady Plan was the Mexican debt reduction of 1989. The deal reduced Mexico's 1989 debt of $107 billion by about $15 billion and until 1995 was widely regarded as a success.16