- •Introduction

- •Relationship between Business and Providers of Capital

- •Political and Economic Ties with Other Countries

- •Inflation Accounting

- •Level of Development

- •Culture

- •Accounting Clusters

- •Consequences of the Lack of Comparability

- •International Standards

- •Consolidated Financial Statements

- •Currency Translation

- •The Current Rate Method

- •The Temporal Method

- •Current us Practice

- •Exchange Rate Changes and Control Systems

- •The Lessard - Lorange Model

- •Transfer Pricing and Control Systems

- •Separation of Subsidiary and Manager Performance

- •In the meantime, current Chinese accounting principles, present difficult problems for Western firms. For

- •Case Discussion Questions

Exchange Rate Changes and Control Systems

Most international businesses require all budgets and performance data within the firm to be expressed in the "corporate currency," which is normally the home currency. Thus, the Malaysian subsidiary of a US multinational would probably submit a budget prepared in US dollars, rather than Malaysian ringgit, and performance data throughout the year would be reported to headquarters in US dollars. This facilitates comparisons between subsidiaries in different countries, and it makes things easier for headquarters management. However, it also allows exchange rate changes during the year to introduce substantial distortions. For example, the Malaysian subsidiary may fail to achieve profit goals not because of any performance problems, but merely because of a decline in the value of the ringgit against the dollar. The opposite can occur, also, making a foreign subsidiary's performance look better than it actually is.

The Lessard - Lorange Model

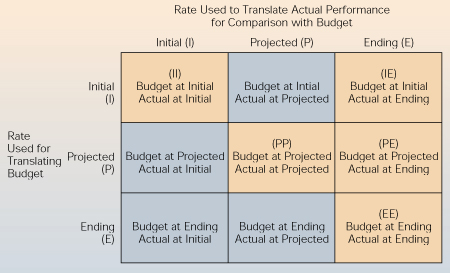

According to research by Donald Lessard and Peter Lorange, a number of methods are available to international businesses for dealing with this problem.15 Lessard and Lorange point out three exchange rates that can be used to translate foreign currencies into the corporate currency in setting budgets and in the subsequent tracking of performance:

The initial rate, the spot exchange rate when the budget is adopted.

The projected rate, the spot exchange rate forecast for the end of the budget period (i.e., the forward rate).

The ending rate, the spot exchange rate when the budget and performance are being compared.

These three exchange rates imply nine possible combinations (see Figure 19.3). Lessard and Lorange ruled out four of the nine combinations as illogical and unreasonable; they are shaded in Figure 19.3. For example, it would make no sense to use Figure 19.3

Possible

Combinations of Exchange Rates in the Control Process

the ending rate to translate the budget and the initial rate to translate actual performance data. Any of the remaining five combinations might be used for setting budgets and evaluating performance.

With three of these five combinations-II, PP, and EE-the same exchange rate is used for translating both budget figures and performance figures into the corporate currency. All three combinations have the advantage that a change in the exchange rate during the year does not distort the control process. This is not true for the other two combinations, IE and PE. In those cases, exchange rate changes can introduce distortions. The potential for distortion is greater with IE; the ending spot exchange rate used to evaluate performance against the budget may be quite different from the initial spot exchange rate used to translate the budget. The distortion is less serious in the case of PE because the projected exchange rate takes into account future exchange rate movements.

Of the five combinations, Lessard and Lorange recommend that firms use the projected spot exchange rate to translate both the budget and performance figures into the corporate currency, combination PP. The projected rate in such cases will typically be the forward exchange rate as determined by the foreign exchange market (see Chapter 9 for the definition of forward rate) or some company-generated forecast of future spot rates, which Lessard and Lorange refer to as the internal forward rate. The internal forward rate may differ from the forward rate quoted by the foreign exchange market if the firm wishes to bias its business in favor of, or against, the particular foreign currency.