- •Introduction

- •Relationship between Business and Providers of Capital

- •Political and Economic Ties with Other Countries

- •Inflation Accounting

- •Level of Development

- •Culture

- •Accounting Clusters

- •Consequences of the Lack of Comparability

- •International Standards

- •Consolidated Financial Statements

- •Currency Translation

- •The Current Rate Method

- •The Temporal Method

- •Current us Practice

- •Exchange Rate Changes and Control Systems

- •The Lessard - Lorange Model

- •Transfer Pricing and Control Systems

- •Separation of Subsidiary and Manager Performance

- •In the meantime, current Chinese accounting principles, present difficult problems for Western firms. For

- •Case Discussion Questions

Chapter 19 Outline

The Adoption of International Accounting Standards in Germany

Introduction

Country Differences in Accounting Standards

Relationship between Business and Providers of Capital

Political and Economic Ties with Other Countries

Inflation Accounting

Level of Development

Culture

Accounting Clusters

National and International Standards

Consequences of the Lack of Comparability

International Standards

Multinational Consolidation and Currency Translation

Consolidated Financial Statements

Currency Translation

Current US Practice

Accounting Aspects of Control Systems

Exchange Rate Changes and Control Systems

Transfer Pricing and Control Systems

Separation of Subsidiary and Manager Performance

Chapter Summary

Critical Discussion Questions

China's Evolving Accounting System

The Adoption of International Accounting Standards in Germany

A number of major German firms have begun to adopt international accounting standards that reveal far more about their financial performance than hitherto. This represents a major shift away from inscrutable German accounting standards that often hid as much about a company's financial performance as they revealed. The change has been driven by a recognition that German capital markets are too narrow and illiquid to satisfy the future funding requirements of many major German companies. These corporations are realizing that it is in their best interests to get a listing on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), the world's largest capital market, as a prelude to issuing equity and raising debt through the New York market.

Historically, German firms have almost never resorted to international capital markets to raise additional equity. Their view was that bank debt was adequate. However, the German market for debt has become expensive, while the possibility of raising additional equity in Germany has been limited by the relatively small and illiquid nature of the German equity market. The move among German firms to raise equity on international capital markets began in the early 1990s when a number of major German firms, including Daimler-Benz, Siemens, and Volkswagen, discretely applied to the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for a listing. The SEC, however, was not particularly responsive. In the SEC's view, German accounting standards were not comparable to those in the United States and did not provide sufficient information to investors. Among the SEC's objections was the German practice of not disclosing the size of a company's financial reserves and pension fund commitments, as well as the more liberal policy for writing down goodwill in Germany, which tended to overstate a firm's financial performance relative to that which would be reported under US accounting rules.

After the initial rebuff from the SEC, this group of firms fell apart quite rapidly. However, Daimler-Benz announced in 1993 that it had reached an agreement with the SEC and would soon have a listing on the NYSE. To achieve this, Daimler-Benz had to issue two sets of accounts, one that adhered to German standards and another that adhered to US generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). When Daimler-Benz reported its 1994 financial results, the impact of using different accounting standards was readily apparent. Under German rules, Daimler-Benz reported a profit of over $100 million, but under GAAP, the company reported a $1 billion loss!

Following the lead of Daimler-Benz, several other German firms have announced that they are willing to adopt international accounting standards. International accounting standards are being devised by a London-based committee of leading accountants that was established in 1973. Since 1987, the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC) has been attempting to harmonize accounting rules that historically have varied significantly from country to country.

The international standards are more forthcoming about financial performance than the German rules. However, they still fall short of the GAAP, primarily because they allow for a looser treatment of goodwill. In March 1995, the pharmaceutical company Schering AG became the first German firm to shift completely to international standards. It was quickly followed by two other major German firms, Bayer AG and Hoechst AG. In 1997, Hoechst became the second German firm to list its shares on the NYSE. To support its listing, Hoechst issued two sets of accounts, one in accordance with IASC principles and one in accordance with GAAP. Under the IASC principles, Hoechst reported profits of $1.2 billion in 1995, and $1.4 billion in 1996. Under the more restrictive GAAP, it lost $40 million in 1995, and $708 million in 1996!

Despite the fact that adhering to GAAP apparently reduces the reported profit of German firms, others seem willing to follow to gain access to the US capital market. For example, Allianz, a large German insurance company, recently adopted IASC principles as a prelude to seeking a listing on the NYSE. Allianz believes such a listing will help it finance acquisitions of other firms in the large US insurance market. Under the IASC principles, Allianz became the first German insurance company to reveal the size of its "hidden reserves"--defined as the difference between the book value of its assets and their current market value. Since insurance companies generally invest the proceeds from insurance premiums in financial assets, such as stocks, and since the value of these assets tends to appreciate as the stock market rises, their market value can be substantial. However, their market value alsofluctuates sharply with the value of the stock market, which is why German companies have preferred to keep them secret. In early 1998, the value of Allianz's hidden assets stood at $56.1 billion, but as the company pointed out, a sharp fall in the value of the stock market would cause a comparable fall in the assets. Nevertheless, because US insurance companies always reveal the market value of such assets, Allianz must do so if it is to list its stock on the NYSE.

http://www.nyse.com

Source: P. Gumbel and G. Steinmetz, "German Firms Shift to More Open Accounting," The Wall Street Journal, March 15, 1995, p. C1; "Daimler-Benz: A Capital Suggestion," The Economist, April 9, 1994, p. 69; L. Berton, "All Accountants May Soon Speak the Same Language," The Wall Street Journal, August 29, 1995, p. A15; R. Atkins, "Allianz Plans to Seek New York Listing," Financial Times, May 29, 1998, p. 30; and G. Meek, "Accountants Gather Round Different Standards," Financial Times, March 20, 1998, p. 12.

Introduction

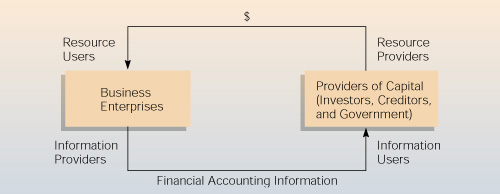

Accounting has often been referred to as "the language of business."1 This language finds expression in profit-and-loss statements, balance sheets, budgets, investment analysis, and tax analysis. Accounting information is the means by which firms communicate their financial position to the providers of capital investors, creditors, and government. It enables the providers of capital to assess the value of their investments or the security of their loans and to make decisions about future resource allocations (see Figure 19.1). Accounting information is also the means by which firms report their income to the government, so the government can assess how much tax the firm owes. It is also the means by which the firm can evaluate its performance, control its internal expenditures, and plan for future expenditures and income. Thus, a good accounting function is critical to the smooth running of the firm.

International businesses are confronted with a number of accounting problems that do not confront purely domestic businesses. The opening case draws attention to one of these problems--the lack of consistency in the accounting standards of different countries. We begin this chapter by looking at the source of these country differences. Then we shift our attention to attempts to establish international accounting and auditing standards--the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC).

We will examine the problems arising when an international business with operations in more than one country must produce consolidated financial statements. As we will see, these firms face special problems because, for example, the accounts for their operations in Brazil will be in real, in Korea they will be in won, and in Japan they will be in yen. If the firm is based in the United States, it will have to decide what basis to use for translating all these accounts into US dollars. The last issue we discuss is control in an international business. We touched on the issue of control in Chapter 13 in rather abstract terms. Here we look at control from an accounting perspective.

Figure 19.1

Accounting

Information and Capital Flows

Country Differences in Accounting Standards

Accounting is shaped by the environment in which it operates. Just as different countries have different political systems, economic systems, and cultures, they also have different accounting systems.2 In each country, the accounting system has evolved in response to the demands for accounting information.

An example of differences in accounting conventions concerns employee disclosures. In many European countries, government regulations require firms to publish detailed information about their training and employment policies, but there is no such requirement in the United States. Another difference is in the treatment of goodwill. A firm's goodwill is any advantage, such as a trademark or brand name (e.g., the Coca-Cola brand name), that enables a firm to earn higher profits than its competitors. When one company acquires another in a takeover, the value of the goodwill is calculated as the amount paid for a firm above its book value, which is often substantial. Under accounting rules prevailing in many countries, acquiring firms are allowed to deduct the value of goodwill from the amount of equity or net worth reported on their balance sheet. In the United States, goodwill has to be deducted from the profits of the acquiring firm over as much as 40 years (although firms typically write down goodwill much more rapidly). If two equally profitable firms, one German and one American, acquire comparable firms that have identical goodwill, the US firm will report a much lower profit than the German firm, because of differences in accounting conventions regarding goodwill.3

Despite attempts to harmonize standards by developing internationally acceptable accounting conventions (more on this later), a myriad of differences between national accounting systems still remain. A study tried to quantify the extent of these differences by comparing various accounting measures and profitability ratios across 22 developed nations, including Australia, Britain, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Japan, Spain, and South Korea.4 The study found that among the 22 countries, there were 76 differences in the way cost of goods sold was assessed, 65 differences in the assessment of return on assets, 54 differences in the measurement of research and development expenses as a percentage of sales, and 20 differences in the calculation of net profit margin. These differences make it very difficult to compare the financial performance of firms based in different nation-states.

Although many factors can influence the development of a country's accounting system, there appear to be five main variables:5

1. The relationship between business and the providers of capital.

2. Political and economic ties with other countries.

3. The level of inflation.

4. The level of a country's economic development.

5. The prevailing culture in a country.

Figure 19.2 illustrates these variables. We will review each in turn.