- •1. Прочитайте текст и составьте аннотацию к нему. Основные приемы аннотирова-

- •2. Ознакомьтесь с основными приемами аннотирования. Аннотирование на английском и русском языках

- •Содержание описательной аннотации

- •Требования к аннотациям

- •Основные штампы аннотаций

- •Работа над аннотацией

- •Примечания

- •Аннотация

ДОМАШНЕЕ ЧТЕНИЕ

1. Прочитайте текст и составьте аннотацию к нему. Основные приемы аннотирова-

ния и образец аннотации прилагаются.

ВАРИАНТ №1

ВАРИАНТ №2

Online security

A security patch for your brain

The quickest way to improve online security is to upgrade your mental software

TWO decades ago only spies and systems administrators had to worry about passwords. But today you have to enter one even to do humdrum things like turning on your computer, downloading an album or buying a book online. No wonder many people use a single, simple password for everything.

Analysis of password databases, often stolen from websites (something that happens with disturbing frequency), shows that the most common choices include “password”, “123456” and “abc123”. But using these, or any word that appears in a dictionary, is insecure. Even changing some letters to numbers (“e” to “3”, “i” to “1” and so forth) does little to reduce the vulnerability of such passwords to an automated “dictionary attack”, because these substitutions are so common. The fundamental problem is that secure passwords tend to be hard to remember, and memorable passwords tend to be insecure.

Weak passwords open the door to fraud, identity theft and breaches of privacy. An analysis by Verizon, an American telecoms firm, found that the biggest reason for successful security breaches was easily guessable passwords. Some viruses spread by trying common passwords. Attacks need only work enough of the time—say, in 1% of cases—to be worthwhile. And it turns out that a relatively short list of passwords provides access to 1% of accounts on many sites and systems.

Fingerprint scanners and devices that generate time-specific codes offer greater security, but they require hardware. Passwords, which need only software, are cheaper. In terms of security delivered per dollar spent, they are hard to beat, so they are not going away. But they need to be made more secure.

The solution, say security researchers, is to upgrade the software in people’s heads, by teaching them to choose more secure passwords. One approach is to use passphrases containing unrelated words, such as “correct horse battery staple”, linked by a mental image. Passphrases are, on average, several orders of magnitude harder to crack than passwords. But a new study by researchers at the University of Cambridge finds that people tend to choose phrases made up not of unrelated words but of words that already occur together, such as “dead poets society”. Such phrases are vulnerable to a dictionary attack based on common phrases taken from the internet. And many systems limit the length of passwords, making a long phrase impractical.

An update is ready for installation

An alternative approach, championed by Bruce Schneier, a security guru, is to turn a sentence into a password, taking the first letter of each word and substituting numbers and punctuation marks where possible. “Too much food and wine will make you sick” thus becomes “2mf&wwmUs”. This is no panacea: the danger with this “mnemonic password” approach is that people will use a proverb, or a line from a film or a song, as the starting point, which makes it vulnerable to attack. The ideal sentence is one like Mr Schneier’s that (until the publication of this article, at least) has no matches in Google.

Some websites make an effort to enhance security by indicating how easily guessed a password is likely to be, rejecting weak passwords, ensuring that password databases are kept properly encrypted and limiting the rate at which login attempts can be made. More should do so. But don’t rely on it happening. Instead, beef up your own security by upgrading your brain to use mnemonic passwords.

ВАРИАНТ №3

ВАРИАНТ №4

Monitor

Pivoting pixels

Computer displays: A new type of display that uses tiny mechanical mirrors to produce coloured dots would work even in bright sunlight

IN A novel called “The Difference Engine”, published in 1990, William Gibson and Bruce Sterling described an alternative Victorian era of mechanical computers driven by steam, with their results displayed on screens made of mechanical pixels. Steam-driven computers remain in the realm of science fiction. Mechanical pixels, however, are beginning to see the light of day.

Pixels are the dots, or “picture elements” that make up the picture on a display screen. And one way of making them change colour is to use what are known as micro-electromechanical systems, or MEMS, to move part of each pixel around, creating iridescent interference patterns in the process. According to Wallen Mphepö of National Chiao Tung University in Hsinchu, Taiwan, who is one of those working on this idea, screens made this way should be as easy on the eye in bright sunlight as the reflective “electronic paper” used in devices such as the Kindle. They would also use far less power than today’s liquid-crystal displays.

Mr Mphepö’s pixels are pieces of zirconium dioxide, 30 microns across, that have been coated on one side with a layer of silver 1.23 microns thick. These tiny mirrors can be tilted electrostatically, using a voltage applied by a thin-film transistor of the sort employed to control liquid-crystal pixels. The upshot is a mirror whose angle with respect to the light incident upon it can be changed at will. Paradoxically, though, it is a mirror in which the silver, being on top, is the transparent layer (it is so thin that light passes easily through it) while the zirconium dioxide (which is normally a transparent substance) acts as the reflective surface. The reason is that zirconium dioxide has a much higher refractive index than silver: in other words, light slows down and bends more when travelling through zirconium oxide than when travelling through silver. It is the junction between the two materials which acts as the reflective surface.

The upshot is that the length of the paths of rays of light entering the silver, bouncing off the mirror, and then returning to the outside world (and so to the viewer) can be changed by varying the angle of tilt. That, in turn, affects how the peaks and troughs of the incident and reflected rays fall on each other. And this, depending on the wavelength of the light concerned (and thus its colour), causes some colours to be amplified while others are cancelled out. The reason for choosing 1.23 microns for the thickness of the silver is that it is twice the average wavelength of visible light. This gives just enough room for the processes of amplification and cancellation to take place.

A similar technique is already used in a commercial display technology developed by Qualcomm, an American electronics company. But Mirasol, as Qualcomm’s method is known, merely uses MEMS to turn a pixel on or off (by reflecting either one wavelength of light or none at all). Mr Mphepö’s approach is more sophisticated, and does not require separate sub-pixels for each of the three primary colours to produce a full-colour image, which could improve the screen’s resolution. They may not be powered by steam, but Mr Mphepö’s pixels may, in their own way, rewrite history.

ВАРИАНТ №5

Corporate fraud

Mind your language

How linguistic software helps companies catch crooks

A

wise thief tries not to draw attention to himself

A

wise thief tries not to draw attention to himself

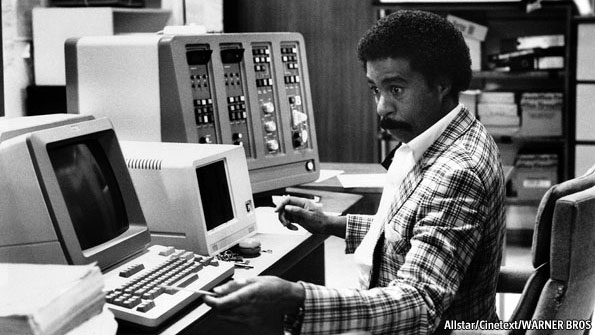

IN THE film “Superman 3”, a lowly computer programmer (played by Richard Pryor, pictured) embezzles a fat wad of money from his employer. The boss laments that it will be hard to catch the thief, because “he won’t do a thing to call attention to himself.

The traditional way to snare them is to hire an accountant to scrutinise accounts for anomalies. But this is like looking for a contact lens in a snowdrift. So firms are turning to linguistic software to narrow the search.

Rip-offs tend to occur in what gumshoes call the “fraud triangle”: where incentive, rationalisation and opportunity meet. To spot staff with the incentive to steal (over and above the obvious fact that money is quite useful), anti-fraud software scans e-mails for evidence of money troubles. Phrases like “under the gun” and “make sales quota” can indicate that an employee is desperate for a bit extra.

Spotting rationalisation is harder. One technique is to identify those who seem unhappy about their jobs, since some may rationalise wrongdoing by telling themselves that their employer is an evil corporation that deserves to be ripped off.

Ernst & Young (E&Y), a consultancy, offers software that purports to show an employee’s emotional state over time: spikes in trend-lines reading “confused”, “secretive” or “angry” help investigators know whose e-mail to check, and when. Other software can help firms find potential malefactors moronic enough to gripe online, says Jean-François Legault of Deloitte, another consultancy.

To work well, linguistic software must adjust to the way different people talk.

Dick Oehrle, the chief linguist on the project, explains how it works. First, the algorithm digests a big bundle of e-mails to get used to employees’ language. Then human lawyers code the same e-mails, sorting things as irrelevant, relevant or serious. The human feedback and the computers’ results are then reconciled, so the system gets smarter. Mr Oehrle says the lawyers also learn from the computers (presumably such things as empathy and the difference between right and wrong).

To find employees with the opportunity to steal, the software looks for what snoops call “out of band” events: messages such as “call my mobile” or “come by my office” suggest a desire to talk without being overheard. E-mails between an employee and an outsider that contain the words “beer”, “Facebook” or “evening” can suggest a personal relationship.

Your e-mails may be aired in court

Financial Tracking Technologies, a firm based in Connecticut, goes a step further, making software that can go through calendar apps and travel-expense claims to determine who has come into contact with certain outside investors.

Employers without such technology are “operating blind”, says Alton Sizemore, a former fraud detective at America’s FBI. They often pursue costly investigations based on hunches, which are usually wrong, he says. Mr Sizemore, who now works for Forensic/Strategic Solutions, an anti-fraud consultancy in Alabama, reckons that nearly all giant financial firms now run anti-fraud linguistic software, but fewer than half of medium-sized or small financial firms do.

So there is plenty of room for growth. NICE Actimize says its revenues are steadily rising, though it declines to give figures. Prospective users typically pay for a single “snapshot” search of 12 months of company records, according to APEX Analytix, a developer of the software in Greensboro, North Carolina. For a company with 10,000 employees, this costs about $45,000. Unless a company is very small, evidence of fraud almost always surfaces, convincing clients to sign up for a yearly package that costs three or four times as much as a spot-check, says John Brocar of APEX Analytix.

Why spend the money? Partly because no one likes to be ripped off. But also because laws on bribery (which is harder to spot than theft) have grown tougher. American bosses can in theory be jailed if their underlings grease palms. Jonas Dischl-Luell of AWK Group, a Swiss firm, sells software that scans e-mail addresses to see if any employees are in contact, even indirectly, with officials in corrupt governments. If a company shows it has systems in place to detect this kind of thing, and starts investigating before outsiders do, it may have an easier time in court.