- •Издательство «высшая школа» Москва — 1971

- •4И (Англ)

- •1 В общий словарь, помещенный после II части книги, эти слова включаются, как правило, лишь в тех случаях, когда они встречаются также в других разделах пособия.

- •I. Pilot-book (лоция) 1. Lights (огни)

- •Vocabulary

- •Exercises

- •I. Translate the following into Russian:

- •II. Find six pairs of words similar in meaning:

- •III. Give synonyms to:

- •VII. Translate the following sentences into English:

- •VIII. Read the following abbreviations in full and give their Rus- sian equivalents:

- •2. Buoys and beacons (буи и береговые знаки)

- •Vocabulary

- •Inverted с. [m'vaitid] конус, повернутый вершиной вниз

- •Expressions

- •Memorize the translation of the following sentences

- •The fairway is buoyed.

- •The fairway is unbuoyed.

- •Leave this buoy to starboard

- •Buoys and beacons a.

- •Exercises

- •I. Translate the following sentences into Russian:

- •II. Form verbs from the following nouns and translate both the nouns and the verbs:

- •V. Fill in these blanks with the following prepositions:

- •VI. Analyse the following sentences and translate them into Russian:

- •3. Dangers (опасности)

- •Vocabulary

- •Memorize the translation of the following sentences

- •Dangers

- •4. Anchorages (якорные стоянки)

- •Vocabulary

- •Expressions

- •To anchor closer in

- •To anchor with the tower

- •Anchorages

- •Exercises

- •XI. Translate the following sentences into English:

- •5. Directions (наставления) vocabulary Слова, относящиеся к наставлениям

- •Expressions

- •Directions

- •I. Translate the following into Russian:

- •II. Select words of similar meaning:

- •IV. Give synonyms to:

- •V. Give antonyms to:

- •6. Tides and tidal streams (приливы, отливы и приливо-отливные течения)

- •Vocabulary

- •Expressions

- •4. The tidal streams are felt in

- •5. The flood stream at springs

- •Tides and tidal streams

- •Exercises

- •VII. Translate the following sentences into English:

- •The main stress is on the 3rd syllable

- •Port facilities

- •I. Give synonyms to:

- •II. Give antonyms to:

- •III. Translate the following sentences into Russian, paying attention to the use of the Infinitive Constructions;

- •II. Charts (карты) 1. Abbreviations (сокращения) Bottom (Грунт)

- •Volcanic white weed yellow

- •Examples

- •Buoys and Beacons (Буи и береговые знаки)

- •Examples

- •2. Headings (заголовки)

- •Vocabulary

- •Increase [in'kri:s] увеличивать

- •Expressions

- •2. For abbreviations see Chart No. 5011—сокращения см. На кар-

- •3. For details of Time Signals see in ... — подробности о сигналах

- •East schelde hook of schouwen to westkapelle from the netherland government surveys to 1939 with corrections to 1942

- •Orfordness and scheveningen to terschelling zeegat compiled from the latest admiralty and foreign government surveys with additions and corrections to 1941

- •3. Notes (примечания)

- •Vocabulary

- •Expressions

- •4. Cautions (предостережения)

- •Vocabulary

- •Expressions

- •The existence and positions of buoys cannot be relied on —

- •Cautions

- •III. List of lights (список огней) the admiralty list of lights fog signals and visual time signals volume 4

- •Corrected to 2nd May

- •London Published by the Hydrographic Department Admiralty

- •Introductory remarks lights

- •Lights, whose Colour does not alter

- •Showing a single flash at regular intervals, the duration of light being always less than that of darkness.

- •A steady light with, at regular intervals, a total eclipse; the duration of light being always less than that of darkness.

- •Iron tower 13

- •IV. Notices to mariners (извещения мореплавателям)

- •Vocabulary

- •Expressions

- •Week ending 13th November, 1954

- •Numerical index of charts affected

- •2580. Admiralty publications new charts

- •2579. Admiralty publications — Admiralty List of Radio Signals, Vol. IV, 1954

- •2566. England, w. Coast — Blackpool — Wreck Buoy Westward withdrawn

- •2526. England, s. Coast — plymouth — Hamoaze-Jetty constructed; Dolphins established

- •2573. North sea — netherlands - (1) The Texel — Information about Wrecks

- •2572. North sea — netherlands — Ijmuiden - Wreck North-North-Westward

- •2519. France, n. Coast — Sandettfe Bank —Wreck

- •2569. France, w. Coast — Rade de Brest — Information about Wrecks and Light — Buoy

- •2525. Mediterranean — archipelago — naxos — Naxia Bay — Wreck removed

- •2521. Black sea — ussr — Novorossiisk Bay — Information about Lights and Beacons

- •2540. Japan — naikai — harima nada — Murotsu Ho Se-Non-existence of Wrecks in vicinity

- •2560. British columbia — dixon entrance — graham island — Rose Spit — Information about Light-and-Whistle-Buoy and Islet.

- •2531. United states, pacific coast — california — Los Angeles Harbour Information about Fog Signals

- •V. Weather reports (метеосводки)

- •Irish sea fastnet lundy ssw force 7 to gale force 8 stop rain and fog at first stop some bright periods tomorrow towards end of period visibility under half mile in fog

- •Current rips

- •VI. Excerpts fpom "the admiralty list of radio signals" (выдержки из „адмиралтейского списка радиосигналов")

- •Coast radio stations, medical and quarantine services, general regulations, etc.

- •Alphabetical list of call signs of coast radio stations

- •Distress signals

- •Alphabetical index of coast radio stations

- •Navigational aids

- •Systems, etc.

- •International Groups Radio Stations

- •Radio direction finding stations

- •Radio direction finding regulations

- •Suspension of radiobeacon services

- •Navigational assistance from radar stations

- •Radio time signals

- •Radio navigational warnings and ice reports service details

- •Ireland

- •II. R/t Transmissions

- •British ships' radio weather reports schedule

- •(Список наиболее важных сокращений, принятых в «Адмиралтейском списке радиосигналов»)

- •I.C.W. Interrupted continuous waves

- •4. Mooring

- •Is it clear astern?

- •Is all clear at the propeller?

- •I. Charter parties and bills of lading

- •Introduction

- •Voyage Charter

- •Exercises

- •II. Bill of lading No. 27

- •The following are the conditions and exceptions hereinbefore referred to:

- •III. Notices of readiness williamson & Co., ltd. Hong kong

- •Notice of readiness to load

- •IV. Ship's protest

- •V. Manifest of cargo

- •VI. English-russian vocabulary

- •In a. With в соответствии с

- •Inward с. ['inwad] импортный груз outward с. ['autwad] экспортный груз (зд. Груз по предыдущему рейсу)

- •In due с. [in 'dju:] в должное время

- •In d. Of при невыполнении чего-либо, за недостатком чего-либо

- •In d. Терпящий бедствие (о судне)

- •In f. Полностью fully ['full] вполне, целиком furnish ['farnif] снабжать, доставлять further [Чэ:5э] дальше, далее

- •Identify [ai'dentifai] опознавать illuminate [I'lu:mineit] освещать immediate [I'mi:dpt] немедленный, срочный

- •Imminent ['iminant] близкий, угрожающий

- •True m. [tru:] истинный меридиан

- •P. Boat [bout] лоцманский бот

- •In respect to [ns'pekt ta] в отношении

- •Identification s. [ai,dentifi'keijn] опознавательный сигнал

- •Visual time s-s ['vizjual taim] визуальные сигналы времени

- •6Yfr buoy

- •Iuap'ball

- •1. Instruments

- •Variation West

- •Variation East

- •2. Fundamentals of the use of radar

- •The radio wave

- •44 Cycle later than a.

- •Directivity of the transmitted wave

- •The propagation of waves

- •The radar horizon

- •Radar pulse being radiated Echoes from both buoys returning

- •Echo from Bi has reached scanner just before transmission has ceased

- •Transmission has ceased. Echo from b2 reaches scanner. Pulse-length 0.25 p-sec: 82 yards minimum range 41 yards Fig. 23. Minimum range

- •Diffraction

- •The display

- •Radar ranges plotted as position circles

- •Radar range and radar bearing

- •Radar range as a clearing line

- •Coasting in general

- •Visual and radar observation compared

- •The information required

- •The relative plot

- •Targets to be plotted

- •Range scale to use

- •Assumptions about the other ship

- •Good Visibility

- •Use in coastal waters

- •Use in pilotage waters

- •Reporting from the plot

- •Radar and the rule of the road at sea

- •Radar detection versus sighting

- •Ascertaining the position of a ship by radar

- •Radar and the steering rules

- •A conclusion

- •Radar brings responsibility

- •3. Azimuths

- •The sextant and its use

Visual and radar observation compared

The circumstances of a daylight meeting with another ship in clear weather leap to the eye. The significant factors which are noted in the mind of the observer are the other ship's bearing and her aspect. Aspect may be defined as the relative bearing of own ship from the other ship. It is measured from 0° to 180° and expressed as "left" (red) or "right" (green) according to whether own ship is on the other ship's port or starboard side, if other ship is steering directly towards own ship her aspect is 0°. Continuous observation of the bearing will very soon establish whether there is a risk of collision and, combined with the aspect, it will usually form the basis for a plan of action, if any is needed, within a very few minutes of the sighting. When avoiding action is taken, any untoward movement on the part of the other ship which might prejudice the manoeuvre's success will be immediately apparent if her aspect remains under close observation. The other ship's speed is not of particular interest in the general clear-weather case, since the avoiding action will presumably be taken while there is still plenty of sea room and its timing has no other significance. Nevertheless, to an experienced mariner, the relations between the other ship's aspect and bearing, and the movement of the bearing will give a good idea of her speed, this may be of value in special circumstances such as a close-range sighting or when manoeuvring is restricted.

Although radar will give bearing information of the same kind and also the range, nothing else can be obtained directly from the PPI, only in exceptional close-range circumstances will the other ship's aspect be discernible. The bearing may be seen to be steady or nearly so, indicating a risk of collision, but the degree of risk and its urgency will not be immediately evident. A slow movement of bearing and a rapid decrease of range may suggest the early development of a close-quarter situation while a similar movement of bearing with a gradual decrease in range may mean that the ships will pass well clear of one another. In clear weather the eye, noting the bearing and aspect, will have no difficulty in distinguishing between these extremes; radar information, however, cannot make the distinction with any certainty unless it is put on paper and further details are deduced from it.

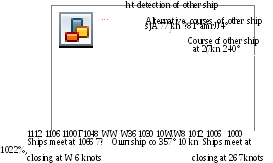

Figure 30 shows how differences in the observed rate of closing imply widely differing aspects. In the example, own ship, which is steering 357° at 10 knots, detects another ship on a steady bearing of 040° with the range decreasing and three possible situations depending on the rate of change of range are shown. If the other ship's speed is 20 knots, her course will be about 240°; if it is 7V2 knots, her course will be either 284° or 334°. In the first case the range will be closing at 26.7 knots and in the second case either 10.6 or 4.2 knots. Thus it will be seen that, depending on the rate of closing, the aspect

of the other ship may vary by as much as 94° in the example taken. If the detection was made, for instance, at a range of 10 miles the ships would be very close after 22 rhinutes in the first case, while in the two others it would take either 56 minutes or 2 hours 24 minutes. One of the extremes in this example constitutes a leisurely overtaking situation, while the other is a highly dangerous crossing situation calling for lively appreciation and early action.

^

\

чч

ч

W30

j

Fig. SO

The rate of closing can be worked out from successive observations of range without any complicated arithmetic, but it is doubtful whether anyone but an expert in mental trigonometry would be able to deduce in his head the aspect of the other ship or construct a reliable picture of the circumstances.