Obstetrics_by_Ten_Teachers_19E_-_Kenny_Louise

.pdf

206Labour

•Backache during and after pregnancy is

not uncommon. There is now good evidence that epidural analgesia does not cause backache.

•Hypotension is now an uncommon complication of epidural anaesthesia, but can still occur

with an epidural although more commonly with a spinal. It can usually be rectified easily with fluid boluses, but may need vasopressors. Occasionally, maternal hypotension will lead to fetal compromise (see below).

•Short-term respiratory depression of the baby is possible because all modern epidural solutions

contain opioids which reach the maternal circulation and may cross the placenta.

Technique

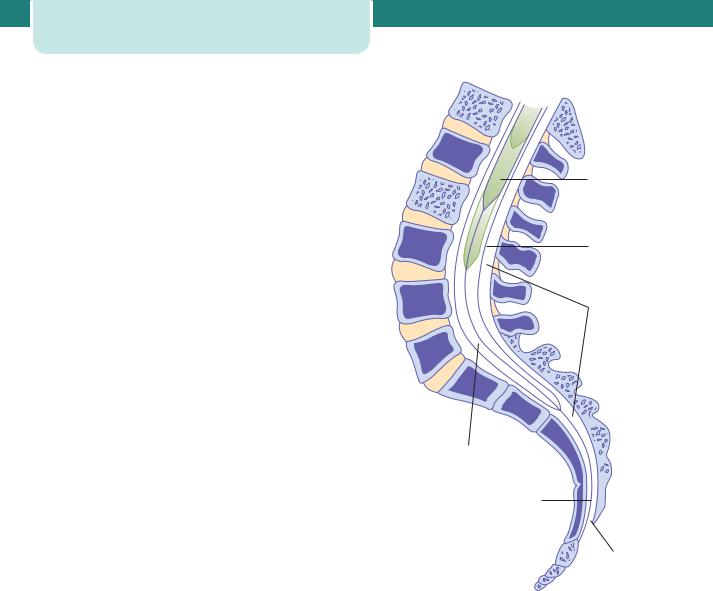

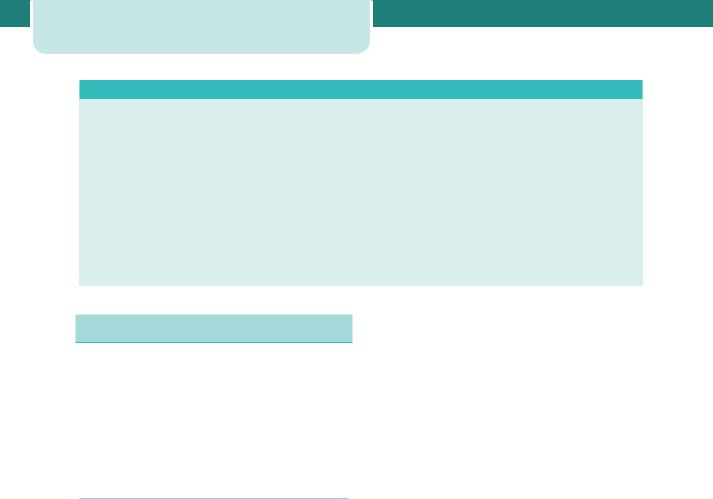

After detailed discussion, the woman’s back is cleansed and local anaesthetic is used to infiltrate the skin. The woman may be in an extreme left lateral position, or sat up but leaning over. Flexion at the upper spine and at the hips helps to open up the spaces between the vertebral bodies of the lumbar spine. Aseptic technique is used. The epidural catheter is normally inserted at the L2–L3, L3–L4 or L4–L5 interspace and should come to lie in the epidural space, which contains blood vessels, nerve roots and fat (Figure 14.22). The catheter is aspirated to check for position and, if no blood or cerebrospinal fluid is obtained, a ‘test dose’ is given to confirm the catheter position (Figure 14.23). This test dose is a small volume of dilute local anaesthetic that would not be expected to have any clinical effect. If indeed it has no obvious effect on sensation in the lower limbs, the catheter is correctly sited. If, however, there is a sensory block, leg weakness and peripheral vasodilatation, the catheter has been inserted too far and into the subarachnoid (spinal) space. Inserting the normal dose of local anaesthetic into the spinal space by accident would risk complete motor and respiratory paralysis. If none of these signs is observed 5 minutes after injection of the test dose, a loading dose can be administered. The epidural solution is usually a mixture of low-concentration local anaesthetic (e.g. 0.0625–0.1 per cent bupivacaine) with an opioid such as fentanyl. Combining the opioid with the local anaesthetic reduces the amount of local anaesthetic required and this reduces the motor blockade and peripheral autonomic effects of the epidural (e.g. hypotension).

|

L1 |

|

Cord |

|

L2 |

L3 |

Dura- |

|

|

|

arachnoid |

L4 |

Epidural |

|

space |

L5

S1

|

S2 |

Subarachnoid |

|

space |

S3 |

|

|

|

Filum |

|

terminal |

CO1 |

Sacral |

|

|

|

hiatus |

Figure 14.22 Sagittal section of the lumbo-sacral spinal cord

After the loading dose is given, the mother should be kept in the right or left lateral position, and her blood pressure should be measured every 5 minutes for 15 minutes. A fall in blood pressure may result from the vasodilatation caused by blocking of the sympathetic tone to peripheral blood vessels. This hypotension is usually short lived, but may cause a fetal bradycardia due to redirection of maternal blood away from the uterus. It should be treated with intravenous fluids and, if necessary, vasoconstrictors such as ephedrine. The mother should never lie supine, as aorto-caval compression can reduce maternal cardiac output and so compromise placental perfusion. Hourly assessment of the level of the sensory block using a cold spray is critical in the detection of a block

Skin |

Spine |

Epidural |

||

|

|

|

space |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dura

a

b

Ligamentum flavum

Figure 14.23 Needle positioning for an epidural anaesthetic. Midline (a) and paramedian (b) approaches

which is creeping too high and risking respiratory compromise. Regional analgesia can be maintained throughout labour with either intermittent boluses or continuous infusions. Patient-controlled epidural analgesia is an option. Women should be encouraged to move around and adopt whichever upright position suits them best. Full mobility is unlikely.

C A S E H I S T O R Y

Pain relief in labour |

207 |

Reducing the rate of an epidural infusion in the second stage may increase the maternal awareness to push, but care should be taken that the analgesic effect is not compromised. Regional anaesthesia should be continued until after completion of the third stage of labour, including repair of any perineal injury.

Spinal anaesthesia

A spinal block is considered more effective than that obtained by an epidural, and is of faster onset. A finegauge atraumatic spinal needle is passed through the epidural space, through the dura and into the subarachnoid space, which contains the cerebrospinal fluid. A small volume of local anaesthetic is injected, after which the spinal needle is withdrawn. This may be used as the anaesthetic for Caesarean sections, trial of instrumental deliveries (in theatre), manual removal of retained placentae and the repair of difficult perineal and vaginal tears. Spinals are not used for routine analgesia in labour.

Combined spinal–epidural (CSE) analgesia has gained in popularity. This technique has the advantage of producing a rapid onset of pain relief and the provision of prolonged analgesia. Because the initiating spinal dose is relatively low, this is a viable option for pain relief in labour.

Mrs W is a 32-year-old para 1 (previous normal vaginal delivery at term), with no medical or obstetric history of note, who realized she was pregnant at approximately 6 weeks gestation. She made an appointment with a local community midwife who confirmed the pregnancy and took a detailed history. In the absence of

risk factors, she was booked under midwifery care. The midwife discussed the options for the place of birth and the woman chose the local obstetric unit because she had elected to have an epidural in her previous labour and thought she would like the

option once again. A dating scan, organized by the midwife, agreed with the menstrual estimated delivery date (EDD), and screening tests in the second trimester were all reassuring. Regular visits through the second and third trimesters did not reveal any new problems.

At 39 weeks gestation, after a week of increasingly uncomfortable but irregular uterine tightenings, Mrs W experienced a ‘show’. Her contractions remained irregular for a further 24 hours. Finally, they began to come frequently and, when they reached every 5 minutes, she phoned her midwife, who recommended assessment at the local maternity unit. Mrs W called her own

parents, who came to look after her first child, and she and her husband drove to the hospital.

On admission, the midwife took a history and performed an abdominal examination. The head was well engaged and the

contractions were coming every 3 minutes. Maternal observations were normal on admission, as was the fetal heart rate when auscultated with a Pinard stethoscope. A vaginal examination showed the membranes to be intact and the cervix to be fully effaced and 4 cm dilated. The vertex was found to be 1 cm above the spines. Mrs W therefore remained under the care of the midwives and the on-call medical staff were not involved.

She remained mobile and continued to drink while in labour, but did not want anything to eat. She spent some time in the bath, as this helped her cope with the pain of the contractions. The midwife listened regularly to the fetal heart, during and after contractions, later choosing to use a hand-held Doppler device. The fetal heart rate remained steady and of a normal rate. Maternal observations also remained normal. Three hours later, her membranes ruptured spontaneously and the liquor was clear. Permission was given for an internal examination and Mrs W was found to be 9 cm dilated.

continued

208 Labour

C A S E H I S T O R Y continued

She was finding the contractions much more painful but, with support and reassurance from her partner and the midwife, did not require anything more than nitrous oxide for analgesia.

One hour later, she was aware of a strong urge to ‘bear down’ and began involuntarily pushing. The midwife confirmed second stage with another vaginal examination and the pushing continued. Mrs W was encouraged to remain upright, but chose to lie in a supine position on the bed. She later found the left lateral position ideal for pushing, as suggested by the midwife. The fetal heart

was listened to during and after each and every contraction during the second stage. Twenty minutes later, the maternal anus began

to dilate slightly and the vertex became visible soon after. Three further contractions later, the head had delivered. The rest of the body came with the fourth. The midwife delivered the baby on to the maternal abdomen and clamped and cut the cord a few minutes later. An intramuscular injection of Syntocinon (oxytocin) was given by a second midwife as the baby was born, and the placenta delivered 5 minutes later, aided by controlled cord traction. She had sustained no perineal damage and the placenta appeared complete. The first breastfeed was established and vitamin K was given to the baby. A check by the paediatrician suggested all was well and Mrs W left hospital 7 hours later with her husband and new baby.

Abnormal labour

Labour becomes abnormal when there is poor progress (as evidenced by a delay in cervical dilatation or descent of the presenting part) and/or the fetus shows signs of compromise. Also, if there is a fetal malpresentation, a multiple gestation, a uterine scar, or if labour has been induced, labour cannot be considered normal.

Poor progress in labour

Poor progress in the first stage of labour

Poor progress in labour has been defined already as cervical dilatation of less than 2 cm in 4 hours, usually associated with failure of descent and rotation of the fetal head.

Progress in labour is dependent on three variables:

1.the powers, i.e. the efficiency of uterine contractions,

2.the passenger, i.e. the fetus (with particular respect to its size, presentation and position),

3.the passages, i.e. the uterus, cervix and bony pelvis.

Abnormalities in one or more of these factors can slow the normal progress of labour. Plotting the findings of serial vaginal examinations on the partogram will help to highlight poor progress during the first stage of labour.

Dysfunctional uterine activity

This is the most common cause of poor progress in labour. It is more common in primigravidae and perhaps in older women and is characterized by

weak and infrequent contractions. The assessment of uterine contractions is most commonly carried out by clinical examination and by using external uterine tocography. However, this can only provide information about the frequency and perhaps duration of contractions. Intrauterine pressure catheters are available and these do give a more accurate measurement of the pressure being generated by the contractions, but they are rarely necessary. A frequency of four to five contractions per 10 minutes is usually considered ideal. Fewer contractions than this does not necessarily mean progress will be slow, but more frequent examinations may be indicated to detect poor progress earlier. Women should be offered hydration, good pain relief and emotional support. When poor progress in labour is suspected it is usual to recommend repeat vaginal examination 2, rather than 4, hours after the last. If delay is confirmed, the woman should be offered artificial rupture of membranes (ARM) and, if there is still poor progress in a further 2 hours, advice should be sought from an obstetrician regarding the use of an oxytocin infusion to augment the contractions. The infusion is commenced at a slow rate initially, and increased carefully every 30 minutes, according to a well-defined protocol. Continuous EFM is necessary as excessively frequent and augmented contractions may cause fetal compromise (see Figure 14.38). Women should be offered an epidural before oxytocin is started, and they need to be aware that although ARM and oxytocin will bring forward the time of birth somewhat, they will not influence the mode of delivery, or other outcomes.

Multiparous women are less likely to experience poor progress in labour secondary to dysfunctional uterine activity. Extreme caution must be exercised

when making this diagnosis in a multiparous woman where an alternative explanation, such as malposition or malpresentation, is more likely. An obstetrician must be closely involved in the assessment of such a woman and the decision to augment with oxytocin must be considered very carefully indeed. Excessive uterine contractions in a truly obstructed labour may result in uterine rupture in a multiparous woman, a complication which is extremely rare in primiparous women. Augmentation with oxytocin is contraindicated if there are concerns regarding the condition of the fetus.

If progress fails to occur despite 4–6 hours of augmentation with oxytocin, a Caesarean section will usually be recommended.

Cephalopelvic disproportion

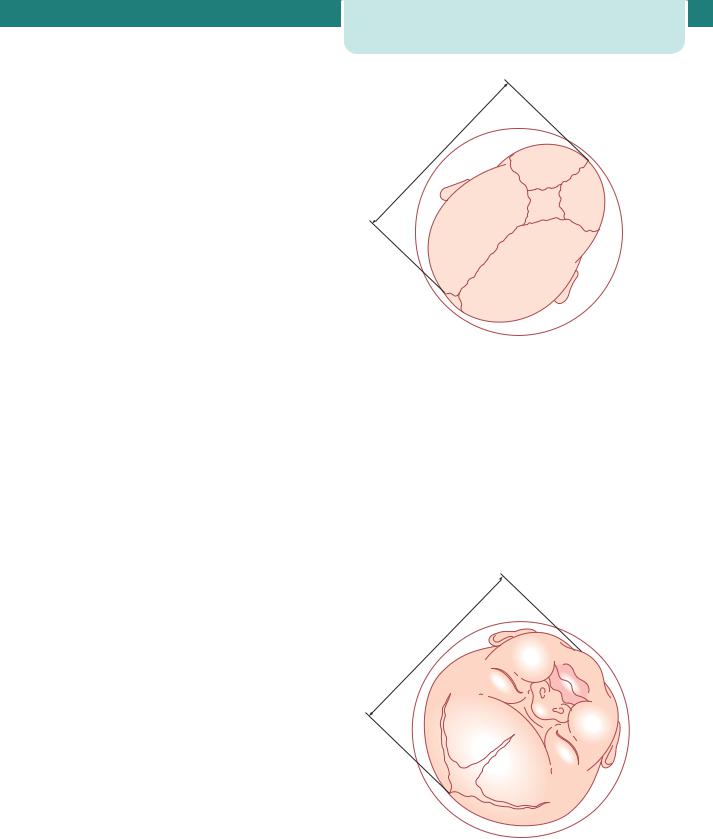

Cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD) implies anatomical disproportion between the fetal head and maternal pelvis. It can be due to a large head, small pelvis or a combination of the two. Women of small stature ( 1.60 m) with a large baby in their first pregnancy are likely candidates to develop this problem. The pelvis may be unusually small because of previous fracture or metabolic bone disease. Rarely, a fetal anomaly will contribute to CPD. Obstructive hydrocephalus may cause macrocephaly, and fetal thyroid and neck tumours may cause extension at the fetal neck. Relative CPD is more common and occurs with malposition of the fetal head. The occipito-posterior position is associated with deflexion of the fetal head and presents a larger skull diameter to the maternal pelvis (Figures 14.14 and 14.24).

Cephalopelvic disproportion is suspected in labour if:

•progress is slow or actually arrests despite efficient uterine contractions;

•the fetal head is not engaged;

•vaginal examination shows severe moulding and caput formation;

•the head is poorly applied to the cervix.

Oxytocin can be given carefully to a primigravida with mild to moderate CPD as long as the CTG is reactive. Relative disproportion may be overcome if the malposition is corrected (i.e. conversion to a flexed OA position). Oxytocin must never be used in a multiparous woman where CPD is suspected.

Abnormal labour |

209 |

11 |

cm |

|

R L

Figure 14.24 Vaginal palpation of the head in the right occipito-posterior position. The circle represents the pelvic cavity, with a diameter of 12 cm. The head is poorly flexed so that the anterior fontanelle is easily felt

Malpresentations

Vital to good progress in labour is the tight application of the fetal presenting part on to the cervix. Face presentations (Figures 14.25 and 14.26) may apply themselves poorly to the cervix and the resulting progress in labour may be poor, although vaginal birth is still possible. Brow presentations are associated with the mento-vertical diameter, which is simply too large

.5 |

cm |

|

|

9 |

|

Figure 14.25 Vaginal examination in the left mento-anterior position. The circle represents the pelvic cavity, with a diameter of 12 cm

210 Labour

Figure 14.26 The mechanism of labour with a face presentation. The head descends with increasing extension. The chin reaches the pelvic floor and undergoes forward rotation. The head is born by flexion

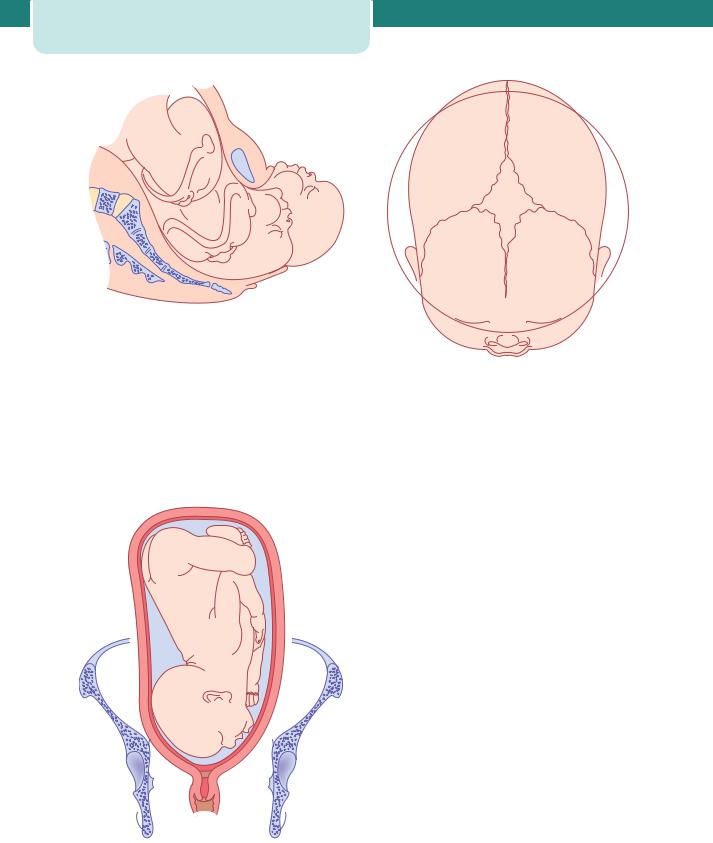

to fit through the bony pelvis unless flexion occurs or hyperextension to a face presentation (Figures 14.27 and 14.28). Brow presentation therefore often manifests as poor progress in first stage, often in a multiparous woman. Shoulder presentations cannot deliver vaginally and once again poor progress will

Figure 14.27 Brow presentation. The head is above the brim and not engaged. The mento-vertical diameter of the head is trying to engage in the transverse diameter at the brim

Figure 14.28 Vaginal examination with brow presentation. The circle represents the pelvic cavity, with a diameter of 12 cm. The mento-vertical diameter of 13 cm is too large to permit engagement of the head

occur. Malpresentations are more common in women of high parity and some carry a risk of uterine rupture if the labour is allowed to continue.

Abnormalities of the birth canal (the ‘passages’)

The bony pelvis may cause delay in the progress of labour as discussed above (CPD). Abnormalities of the uterus and cervix can also delay labour. Unsuspected fibroids in the lower uterine segment can prevent descent of the fetal head. Delay can also be caused by ‘cervical dystocia’, a term used to describe a non-compliant cervix which effaces but fails to dilate because of severe scarring, usually as a result of a previous cone biopsy. Caesarean section may be necessary. It is rare for the soft tissues of the pelvic floor to cause significant delay in labour.

Poor progress in the second stage of labour

Birth of the baby is expected to take place within 3 hours of the start of the active second stage (pushing) in nulliparous women, and 2 hours in parous women. Delay is diagnosed if delivery is not imminent after 2 hours of pushing in a nulliparous labour (1 hour for a parous woman). The causes of second-stage delay can again be classified as abnormalities of the powers, the passenger and the passages. Secondary uterine inertia is a common cause of second stage delay, and

|

|

Abnormal labour |

211 |

Figure 14.29 Deep transverse arrest of the head

may be exacerbated by epidural analgesia. Having achieved full dilatation, the uterine contractions become weak and ineffectual and this is sometimes associated with maternal dehydration and ketosis. If no mechanical problem is anticipated, the treatment is with rehydration and intravenous oxytocin, if the woman is primiparous. Delay can also occur because of a persistent OP position of the fetal head. In this situation, the head will either have to undergo a long rotation to OA or be delivered in the OP position, i.e. face to pubes. By the time delay in second stage in labour has been diagnosed, NICE recommend that oxytocin should not be started. Inefficient uterine activity therefore needs to be corrected proactively at the beginning of the second stage.

Delay in the second stage can also occur because of a narrow mid-pelvis (android pelvis), which

prevents internal rotation of the fetal head. This may result in the arrest of the descent of the fetal head at the level of the ischial spines in the transverse position, a condition called deep transverse arrest (Figure 14.29).

Instrumental birth should be considered for prolonged second stage (see Chapter 15, Operative intervention in obstetrics). This may be safely performed in the labour room, or may be more safely carried out in theatre with easy recourse to Caesarean delivery if the attempt is unsuccessful, or if an attempt is deemed unwise when the woman is examined with the benefits of effective anaesthesia.

Risk factors for poor progress in labour

•Small woman

•Big baby

•Dysfunctional uterine activity

•Malpresentation

•Malposition

•Early membrane rupture

•Soft-tissue/pelvic malformation

Patterns of abnormal progress in labour

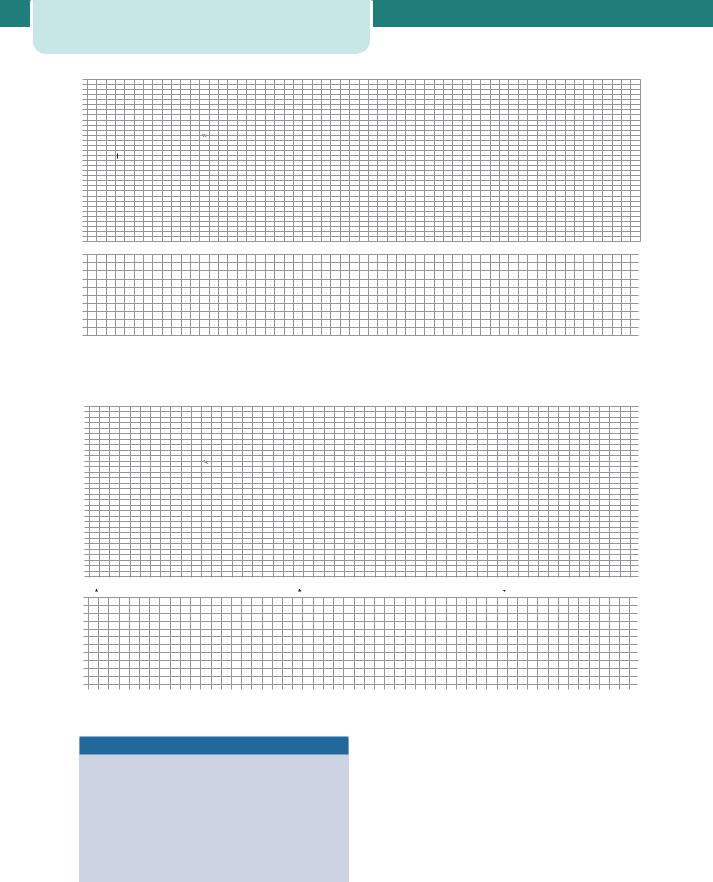

The use of a partogram to plot the progress of labour improves the detection of poor progress. Indeed, three patterns of abnormal labour are commonly described (Figure 14.30).

|

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(cm) |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

phase |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

dilatation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

tive |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ac |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cervical |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

e |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

ph |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

tent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

L |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

Time (hours)

Normal labour |

|

Primary dysfunctional labour |

|

||

Secondary arrest |

|

Prolonged latent phase |

|

Figure 14.30 Abnormalities of the partogram

212 Labour

Prolonged latent phase occurs when the latent phase is longer than the arbitrary time limits discussed previously. It is more common in primiparous women and probably results from a delay in the chemical processes that occur within the cervix which soften it and allow effacement. Prolonged latent phase can be extremely frustrating and tiring for the woman. However, intervention in the form of ARM or oxytocin infusion will increase the likelihood of poor progress later in the labour and the need for Caesarean birth. It is best managed away from the labour suite with simple analgesics, mobilization and reassurance. ‘Primary dysfunctional labour’ is the term used to describe poor progress in the active phase of labour ( 2 cm cervical dilatation/4 hours) and is also more common in primiparous women. It is most commonly caused by inefficient uterine contractions, but can also result from CPD and malposition of the fetus. Secondary arrest occurs when progress in the active phase of first stage is initially good but then slows, or stops altogether, typically after 7 cm dilatation. Although inefficient uterine contractions may be the cause, fetal malpositions, malpresentations and CPD feature more commonly than in primary dysfunctional labour.

Key points

Poor progress in labour

•There are different patterns of poor progress in labour.

•Inefficient uterine activity is the most common cause of poor progress in labour.

•Fetal malposition, malpresentation and true CPD are other causes of poor progress, and may occur in isolation or in combination with inefficient uterine contractions.

•ARM is a simple intervention which may shorten labour, but does not influence the overall outcome.

•The use of oxytocin is relatively safe in nulliparous women.

•Use of oxytocin augmentation in multiparous women is less safe because of the greater risk of uterine hyperstimulation, fetal compromise and uterine rupture in the face of obstruction.

•Oxytocin does not have a significant impact on the mode of delivery, but does shorten the length of labour.

Fetal compromise in labour

Concern for the well-being of the fetus is one of the most common reasons for medical intervention during labour. The fetus may already be compromised

before labour, and the reduction in placental blood flow associated with contractions may uncover this and ultimately lead to fetal hypoxia and eventually acidosis. Fetal compromise may present as fresh meconium staining to the amniotic fluid, or an abnormal CTG. However, neither of these findings confirms fetal hypoxia or acidosis. Meconium can be passed for benign reasons, such as fetal maturity, and it is well recognized that the abnormal CTG carries a very high false-positive rate for the diagnosis of fetal compromise. Intervention for ‘presumed fetal compromise’ is therefore more accurate than ‘fetal distress’. In many cases, babies delivered by Caesarean section or instrumental birth for presumed fetal compromise are found to be in good condition.

Risk factors for fetal compromise in labour

•Placental insufficiency – intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and pre-eclampsia

•Prematurity

•Postmaturity

•Multiple pregnancy

•Prolonged labour

•Augmentation with oxytocin

•Uterine hyperstimulation

•Precipitate labour

•Intrapartum abruption

•Cord prolapse

•Uterine rupture/dehiscence

•Maternal diabetes

•Cholestasis of pregnancy

•Maternal pyrexia

•Chorioamnionitis

•Oligohydramnios

Recognition of fetal compromise

Meconium staining of the amniotic fluid is considered significant when it is either thick or tenacious, dark green, bright green or black. Any particulate meconium should also be of concern. Thin and light meconium is more likely to represent fetal gut maturity than fetal compromise. However, when any meconium is seen in the liquor, consideration should be given to starting continuous EFM with the CTG and this is mandatory

|

|

Abnormal labour |

213 |

if the meconium is thick and dark. Another reason for commencing the CTG is if a change in the heart rate is noted with intermittent auscultation, particularly fetal tachycardia, bradycardia or fetal heart rate decelerations. The CTG may have already been running throughout the labour because of underlying risk factors which predate the labour.

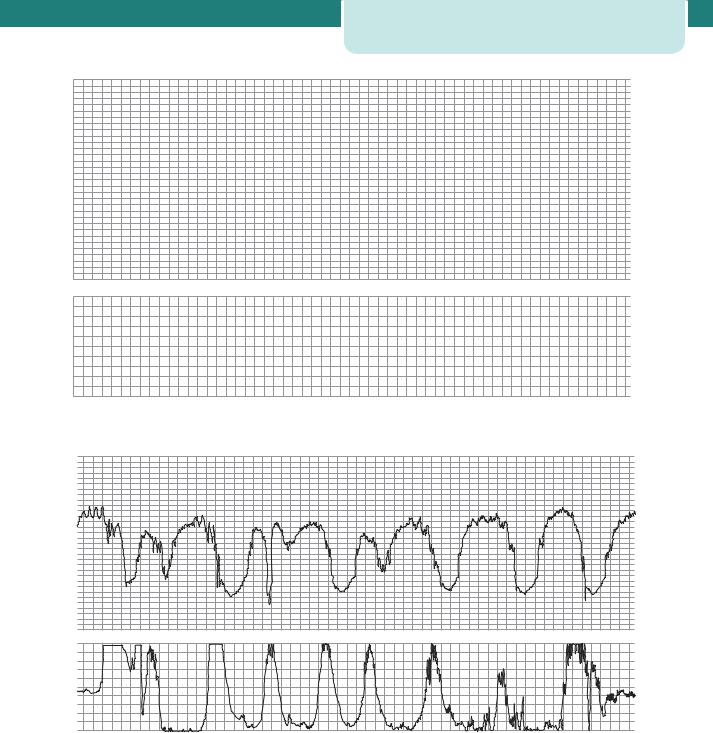

Interpretation of the CTG is a skilled business, and there is significant inter-observer variability. There are national guidelines, which should be used to classify the CTG as ‘normal’, ‘suspicious’ or ‘pathological’. Interpretation of the CTG is discussed in more detail in Chapter 6, Antenatal imaging and assessment of fetal well-being. Examples are given in Figures 14.31–14.36.

|

—DE—DEOG |

200 |

|

200 |

—DEOG |

|

200 |

|

|

|

180 |

|

180 |

|

|

180 |

|

|

|

160 |

|

160 |

|

|

160 |

|

|

|

140 |

|

140 |

|

|

140 |

|

|

|

120 |

|

120 |

|

|

120 |

|

|

|

100 |

|

100 |

|

|

100 |

|

|

|

80 |

|

80 |

|

|

80 |

|

|

|

60 |

|

60 |

|

|

60 |

|

13:40 30.08.06 1cm/min |

13:44 30.08.06 1cm/min |

13.50 30.08.06 1cm/min |

|

|

14:00 30.08.06 1cm/min |

|

|

|

|

12 |

100 |

12 |

100 |

|

12 |

100 |

|

|

80 |

80 |

—TOCOext |

80 |

||||

—TO—TOCOext 10 |

10 |

10 |

||||||

|

||||||||

|

8 |

60 |

8 |

60 |

|

8 |

60 |

|

|

6 |

40 |

6 |

40 |

|

6 |

40 |

|

|

4 |

4 |

|

4 |

||||

|

20 |

20 |

|

20 |

||||

|

2 |

2 |

|

2 |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

137 kPa |

|

138 |

kPa |

|

139 |

kPa |

M 1911A |

|

|

M 1911A |

|

M 1911A |

|

Figure 14.31 Fetal tachycardia with a heart rate of 190 bpm |

|

|

|

|

||

200 |

|

200 |

|

|

200 |

|

–US2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

180 |

|

180 |

|

|

180 |

|

160 |

|

160 |

|

|

160 |

|

140 |

|

140 |

|

|

140 |

|

120 |

|

120 |

|

|

120 |

|

100 |

|

100 |

|

|

100 |

|

80 |

|

80 |

|

|

80 |

|

60 |

|

60 |

|

|

60 |

|

14:50 30.08.06 1cm/min |

|

15:00 30.08.06 1cm/min |

|

15:10 30.08.06 1cm/min |

||

100 |

12 |

100 |

|

12 |

100 |

12 |

80 |

80 |

|

80 |

|||

10 |

|

10 |

10 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

—TOCOext |

60 |

|

8 |

60 |

8 |

|

60 |

8 |

|

||||

40 |

6 |

40 |

|

6 |

40 |

6 |

4 |

|

4 |

4 |

|||

20 |

20 |

|

20 |

|||

2 |

|

2 |

2 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

47 |

kPa |

|

|

48 kPa |

|

49 kPa |

M 1911A |

|

M 1911A |

|

|

M 1911A |

|

Figure 14.32 Fetal bradycardia to a heart rate of 90 bpm, lasting approximately 11 minutes

214 |

Labour |

|

|

|

|

|

|

200 |

|

200 |

|

200 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

–US2 |

|

180 |

|

180 |

|

180 |

|

|

160 |

|

160 |

|

160 |

|

|

140 |

|

140 |

|

140 |

|

|

120 |

|

120 |

|

120 |

|

|

100 |

|

100 |

|

100 |

|

|

80 |

|

80 |

|

80 |

|

|

60 |

|

60 |

|

60 |

|

|

100 |

13:40 09.08.06 1cm/min |

13:50 09.08.06 1cm/min |

14:00 09.08.06 1cm/min |

||

|

12 |

100 |

12 |

100 |

12 |

|

|

80 |

80 |

80 |

|||

|

10 |

10 |

—TOCOext |

|||

|

|

|

|

10 |

||

|

60 |

8 |

60 |

8 |

60 |

8 |

|

40 |

6 |

40 |

6 |

40 |

6 |

|

4 |

4 |

4 |

|||

|

20 |

20 |

20 |

|||

|

2 |

2 |

2 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

95 |

kPa |

|

96 kPa |

|

97 kPa |

|

M 1911A |

|

M 1911A |

|

M 1911A |

|

|

Figure 14.33 Loss of baseline variability ( 5 bpm), with a fetal heart rate of 140 bpm |

|

||||

|

200 |

|

|

200 |

|

200 |

|

180 |

|

|

180 |

|

180 |

|

100 |

|

100 |

|

100 |

|

|

80 |

|

80 |

|

80 |

|

|

60 |

|

60 |

|

60 |

|

13:30 |

100 |

13:40 |

100 |

13:50 |

100 |

|

12 |

12 |

12 |

||||

|

|

|

||||

10 |

80 |

10 |

80 |

10 |

80 |

|

|

|

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Figure 14.34 Fetal heart rate: early decelerations

CTG signs suggestive of fetal compromise

•Fetal tachycardia ( 160 bpm, or a steady rise over the course of the labour)

•Loss of baseline variability ( 5 bpm)

•Recurrent late decelerations

•Persistent variable decelerations

•Fetal bradycardia ( 100 bpm for more than 3 minutes)

Management of possible fetal compromise

A number of resuscitative manoeuvres should be considered when a CTG is classified as ‘suspicious’. It is reasonable to continue observation of the CTG and more complex intervention is not required. If a CTG becomes ‘pathological’, these reversible factors should also be considered, but it is also important to carry out an immediate vaginal examination to exclude malpresentation and cord prolapse and to assess the

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abnormal labour |

215 |

|

|

|

|

200 |

|

|

200 |

|

|

200 |

|

|

|

|

—DECG |

—DECG |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

—US2 —US2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

180 |

|

|

180 |

|

|

180 |

|

|

|

|

160 |

|

|

160 |

|

|

160 |

|

|

|

|

140 |

|

|

140 |

|

|

140 |

|

|

|

|

120 |

|

|

120 |

|

|

120 |

|

|

|

|

12.35 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

100 |

|

|

100 |

|

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

VE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

80 |

|

|

80 |

|

|

80 |

|

|

|

|

|

FSG |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

60 |

|

|

60 |

|

|

60 |

|

|

|

|

12:30 13.07.02 1cm/min |

12:35 13.07.02 1cm/min |

12:40 13.07.02 1cm/min |

|

12:50 13.07.02 |

|

||

|

|

12 |

100 |

|

12 |

100 |

|

12 |

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

10 |

80 |

—TOCOext |

10 |

80 |

|

10 |

80 |

|

|

|

—TOCOE—TOCOext |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

8 |

60 |

|

8 |

60 |

|

8 |

60 |

|

|

|

6 |

40 |

|

6 |

40 |

|

6 |

40 |

|

|

|

4 |

|

4 |

|

4 |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

2 |

20 |

|

2 |

20 |

|

2 |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

102 kPa |

|

|

103 kPa |

|

|

104 kPa |

|

|

Figure 14.35 |

Fetal heart rate: variable decelerations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

200 |

|

|

200 |

|

|

200 |

|

|

|

|

180 |

|

|

180 |

|

|

180 |

|

|

|

|

160 |

|

|

160 |

|

|

160 |

|

|

|

|

140 |

|

|

140 |

|

|

140 |

|

|

|

|

120 |

|

|

120 |

|

|

120 |

|

|

|

|

100 |

|

|

100 |

|

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

80 |

|

|

80 |

|

|

80 |

|

|

|

|

60 |

|

|

60 |

|

|

60 |

|

|

21:01 01.09.03 1cm/min |

22:00 01.09.03 1cm/min |

|

100 |

22:10 01.09.03 1cm/min |

|

100 |

22:20 01 |

|

||

|

12 |

100 |

|

12 |

|

12 |

|

|

||

|

80 |

|

80 |

|

80 |

|

|

|||

—TOCOext |

10 |

|

10 |

|

10 |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

8 |

60 |

|

8 |

60 |

|

8 |

60 |

|

|

|

6 |

40 |

|

6 |

40 |

|

6 |

40 |

|

|

|

4 |

|

4 |

|

4 |

|

|

|||

|

20 |

|

20 |

|

20 |

|

|

|||

|

2 |

|

2 |

|

2 |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

096 |

0 |

0 |

097 |

0 |

0 |

098 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

kPa |

kPa |

|

kPa |

|

|

|

||||

Figure 14.36 Fetal heart rate: late decelerations

progress of the labour. If the cervix is fully dilated, it may be possible to deliver the baby vaginally using the forceps or ventouse. Alternatively, if the cervix is not fully dilated, a fetal blood sampling can be considered. This is usually only possible when the cervix is dilated 3 cm or more. A normal result will permit labour to

continue, although it may need to be repeated every 30–60 minutes if the CTG abnormalities persist or worsen. An abnormal result mandates immediate delivery, by Caesarean section if the cervix is not fully dilated. An instrumental delivery may be possible if the cervix is fully dilated.