Obstetrics_by_Ten_Teachers_19E_-_Kenny_Louise

.pdf

196Labour

possible from home or a midwifery-run unit. Women with issues which increase the chances of problems occurring during labour should be recommended to deliver in an obstetric unit and NICE have published a list of obstetric, fetal and medical factors to help guide midwives and obstetricians when they are counselling women. Also, a variety of indications are listed for intrapartum transfer into an obstetric unit, including high maternal pyrexia in labour, delay in labour, concerns regarding fetal well-being, hypertension, retained placenta and complicated perineal trauma requiring suturing.

Management of normal labour

Women are told to contact their local labour suite or their community midwife if they think their waters may have broken (rupture of membranes) or when their contractions are occurring every 5 minutes or more. It is important to recognize that women have very different thresholds for seeking advice and reassurance. The need for pain relief may result in admission to hospital before either of these two criteria is reached. Whether at home or in hospital, the attending midwife will then make an assessment of the situation based on the history and on clinical examination.

History

The following are important points to note in the admission history:

•Details of previous births and the size of previous babies (the uneventful birth of normal or large

babies is encouraging). A previous Caesarean section, for example, is an adverse feature, especially if it was performed because of a mechanical problem.

•The frequency, duration and perception of strength of the contractions and when they began.

•Whether the membranes have ruptured and, if so, the colour and amount of amniotic fluid lost.

•The presence of abnormal vaginal discharge or bleeding.

•The recent activity of the fetus.

•Any medical issues of note that may influence the labour and delivery, e.g. pregnancy-induced

hypertension, fetal growth restriction.

•Does she have any special requirements, e.g. an interpreter, or particular emotional/psychological

needs?

•What are her expectations of the labour and delivery? Has she made a birth plan? What did she

hope to use for pain relief?

General examination

It is important to recognize women who have a raised body mass index, as this may complicate the management of labour. The temperature, pulse and blood pressure must be recorded and a sample of urine tested for protein, blood, ketones, glucose and nitrates.

Abdominal examination

After the initial inspection for scars indicating previous surgery, it is important to determine the lie of the fetus (longitudinal, transverse or oblique) and the nature of the presenting part (cephalic or breech). If it is a cephalic presentation, the degree of engagement must be determined. A head that remains high and unengaged is a poor prognostic sign for successful delivery. If there is any doubt as to the presentation or if the head is high (five-fifths palpable), an ultrasound scan will determine the presenting part or the reason for the high head (e.g. OP position, deflexed head, placenta praevia, fibroid, etc.) An attempt to estimate the size of the fetus should be made.

Abdominal examination also includes an assessment of the contractions; this takes time (at least 10 minutes) and is done by palpating the uterus directly, not by looking at the tocograph, which provides information only on the frequency and duration of contractions, not the strength.

Vaginal examination

A full explanation of the purpose and technique of vaginal examination is given to the woman and her consent must be obtained. Many women find vaginal examinations extremely distressing and every effort should be made to maintain the woman’s dignity and privacy. The index and middle fingers are passed to the top of the vagina and the cervix. The cervix is examined for dilatation, effacement and application to the presenting part. The dilatation is estimated digitally in centimetres. When no cervix can be felt,

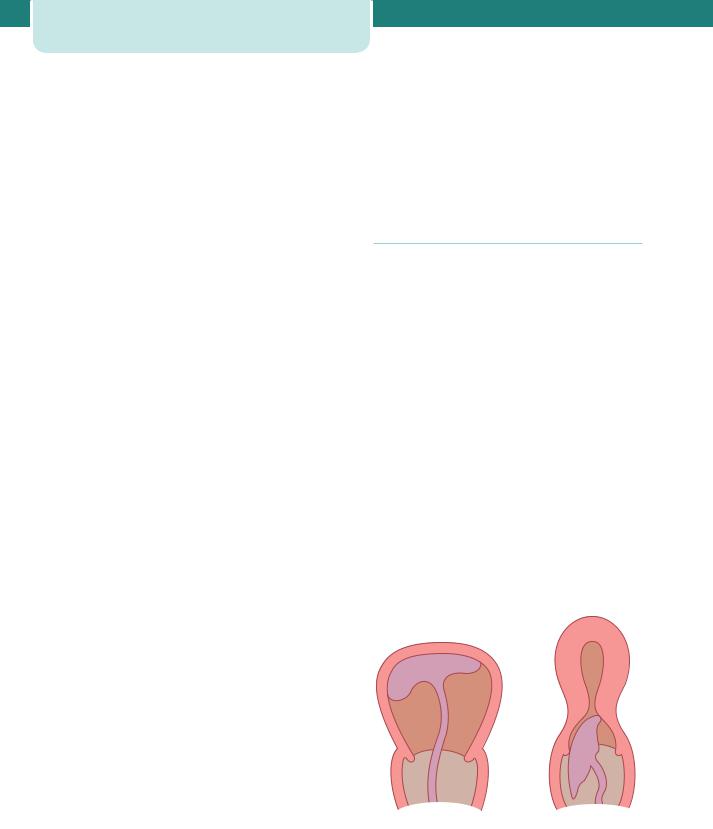

this means the cervix is fully dilated (10 cm). The length of the cervix should be recorded. The cervix at 36 weeks is about 3 cm long. It gradually shortens by the process of effacement. In early labour, it may still be uneffaced. At about 4 cm of dilatation, the cervix should be fully effaced. Providing the cervix is at least 4 cm dilated, it should be possible to determine both the position and the station of the presenting part.

In a normal labour, the vertex will be presenting and the position can be determined by locating the occiput. The occiput is identified by feeling for the triangular posterior fontanelle. Failure to feel the posterior fontanelle may be because the head is deflexed, the occiput is posterior or there is so much caput that the sutures cannot be felt. All of these indicate the possibility of a prolonged labour. Normally, the occiput will be transverse (OT position) or anterior (OA). Relating the lowest part of the head to the ischial spines will give an estimation of the station. This vaginal assessment of station should always be taken together with assessment of the degree of engagement by abdominal palpation. If the head is at or below the ischial spines (0 to 1 or more) and the occiput is anterior (OA), the outlook is favourable for vaginal delivery.

The condition of the membranes should also be noted. If they have ruptured, the colour and amount of fluid draining should be noted. Copious amounts of clear fluid are a good prognostic feature; scanty, heavily blood-stained or meconium-stained fluid is a warning sign for fetal compromise.

Women who are found not to be in established labour should be offered appropriate analgesia and support. Most can safely go home, to return when the contractions increase in strength and frequency.

The admission history and examination act as an initial screen for abnormal labour and increased maternal/fetal risk. If all features are normal and reassuring, the woman will remain under midwifery care. If there are risk factors identified, medical involvement in the form of the on-call obstetric team may be appropriate.

Women in labour should have their pulse measured hourly and their temperature and blood pressure every 4 hours. The frequency of contractions should be recorded every 30 minutes and a vaginal examination performed every 4 hours (unless other factors suggest it needs to be repeated on a different time-frame). It should be noted when the woman voids urine, and this should be tested for ketones and

Management of normal labour |

197 |

protein. Once the second stage is reached, the blood pressure and pulse should be performed hourly, and vaginal examinations offered every hour also.

Fetal assessment in labour

A healthy term fetus is usually able to withstand the rigours of a normal labour. However, with each contraction, placental blood flow and oxygen transfer are temporarily interrupted and a fetus that is already compromised before labour will become increasingly so. Insufficient oxygen delivery to the fetus causes a switch to anaerobic metabolism and results in the generation of lactic acid and hydrogen ions. In excess, these saturate the buffering systems of the fetus and cause a metabolic acidosis which, in the extreme, can cause neuronal damage and permanent neurological injury, even intrapartum fetal death. Hypoxia and acidosis cause a characteristic change in the fetal heart rate pattern, which can be detected by ausculatation and the cardiotocograph (CTG). Meconium is often passed by a healthy fetus at or after term as a result of maturation of gastrointestinal physiology; in this scenario, it is usually thin and a very dark green or brown colour. However, it may also be expelled from a fetus exposed to marked intrauterine hypoxia or acidosis; in this scenario, it is often thicker and much brighter green in colour.

Fetal assessment in labour takes four forms:

1.observation of the colour of the liquor – fresh meconium staining and heavy bleeding are markers of potential fetal compromise

2.intermittent auscultation of the fetal heart using a Pinard stethoscope or a hand-held Doppler ultrasound,

3.continuous external fetal monitoring (EFM) using CTG,

4.fetal scalp blood sampling (FBS).

The fetal heart rate (FHR) should be auscultated with a Pinard stethoscope, or by using a hand-held Doppler device, early on in the initial assessment. It should be listened to for at least a minute, immediately after a contraction. This should be repeated every 15 minutes during first stage, and at least every 5 minutes in second stage. The practice of performing an ‘admission cardiotocograph’ on all women is no longer recommended, however a CTG should be performed if there are issues which might

198Labour

complicate labour and delivery. Most of these women will also be advised to have continuous electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) throughout labour, using the CTG. This may negatively impact on their mobility. Women who begin labour with intermittent auscultation may be advised to change to continuous EFM if any of the following events occur during their labour:

•significant meconium staining to the liquor;

•abnormal fetal heart rate detected by intermittent auscultation;

•maternal pyrexia;

•fresh vaginal bleeding;

•augmentation of contractions with oxytocin;

•at the request of the woman.

The quality of a CTG recording is sometimes poor because of fetal position or maternal obesity. A fetal scalp electrode may overcome this problem. It is fixed into the skin of the fetal scalp and picks up the fetal heart rate directly. It rarely causes any harm to the fetus but requires a certain degree of cervical dilatation to be fitted, and for the membranes to be ruptured if they have remained intact.

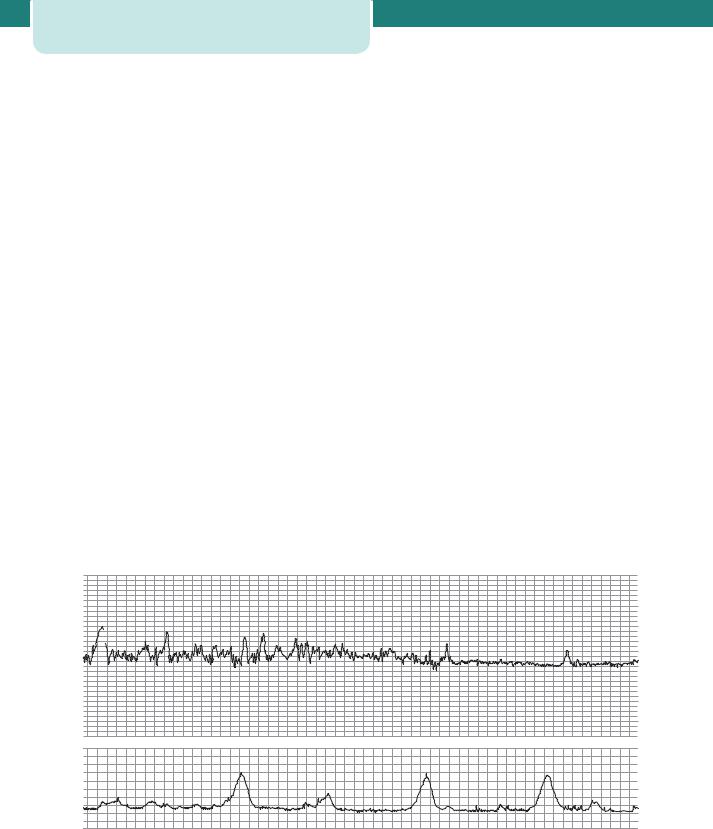

The interpretation of the fetal heart rate pattern on a CTG is discussed in Chapter 6, Antenatal imaging and assessment of fetal well-being. In brief,

features of a normal fetal heart rate pattern include a baseline rate of between 110 and 160 bpm (beats per minute), a baseline variability of between 5 and 25 bpm, and the absence of decelerations. Interpreting the CTG in labour is somewhat different to that of an antenatal CTG, particularly in second stage. The absence of accelerations is of uncertain significance during labour, and the presence of simple variable decelarations, or early decelerations, later on in labour is extremely common and not usually a sign of significant fetal compromise.

Each feature of the CTG (baseline rate, variability, decelerations and accelerations) should be assessed each time a CTG is reviewed. Each feature can be described as ‘reassuring’, ‘non-reassuring’ or ‘abnormal’ according to certain strict nationally agreed definitions outlined in the NICE guideline on intrapartum management. If all four features are reassuring then the CTG is considered ‘normal’ (see Figure 14.18). If one feature is non-reassuring (and the other three are reassuring) then the CTG is described as ‘suspicious’. If there are two or more nonreassuring features, or any abnormal features, then the CTG is ‘pathological’. Any reversible causes must be considered and addressed and further assessment of the fetus made with fetal blood sampling. If this is not possible or safe then the baby should be delivered without delay.

|

|

200 |

|

|

|

200 |

|

|

|

|

180 |

|

|

|

180 |

|

|

|

|

160 |

|

|

|

160 |

|

|

|

|

140 |

|

|

|

140 |

|

|

|

|

120 |

|

|

|

120 |

|

|

|

|

100 |

|

|

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

80 |

|

|

|

80 |

|

|

|

|

60 |

|

|

|

60 |

|

|

09.05.07 1cm/min |

12 |

100 |

09.05.07 1cm/min |

|

12 |

100 |

09.05.07 1cm/min |

12 |

|

80 |

|

|

80 |

|

|||

|

10 |

|

|

10 |

|

10 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

8 |

60 |

|

|

8 |

60 |

|

8 |

|

6 |

40 |

|

|

6 |

40 |

|

6 |

|

4 |

|

|

4 |

|

4 |

||

|

20 |

|

|

20 |

|

|||

|

2 |

|

|

2 |

|

2 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

013 |

0 |

0 |

|

014 |

0 |

0 |

015 |

0 |

kPa |

|

|

kPa |

|

kPa |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 14.18 A normal cardiotocograph (CTG), showing a baseline fetal heart rate of approximately 120 bpm, frequent accelerations, baseline variability of 10–15 bpm and no decelerations. The uterus is contracting approximately once every 5 minutes

Unfortunately, the CTG can be difficult to interpret and it carries a significant false-positive rate, i.e. it often raises the possibility of fetal compromise when in truth the fetus is still in good condition. In order that the use of the CTG does not lead to unnecessary intervention, a fetal blood sampling may be performed during labour to measure fetal pH and base excess directly (see below under Management of possible fetal compromise). Often, these results are normal even when the CTG is abnormal.

The use of electronic fetal monitors, only introduced in the 1970s, has been controversial and their value in ‘low-risk’ labours is doubtful. Education and training are crucial in the proper use of all equipment. Unfortunately, these devices were introduced before CTG recordings and their outcomes were fully understood. There is little doubt that babies’ lives have been saved by the use of electronic fetal monitors, but they have also contributed to the rise in the Caesarean section and instrumental delivery rates and they lead to reduced mobility in labour and increased parental anxiety. This remains a challenge.

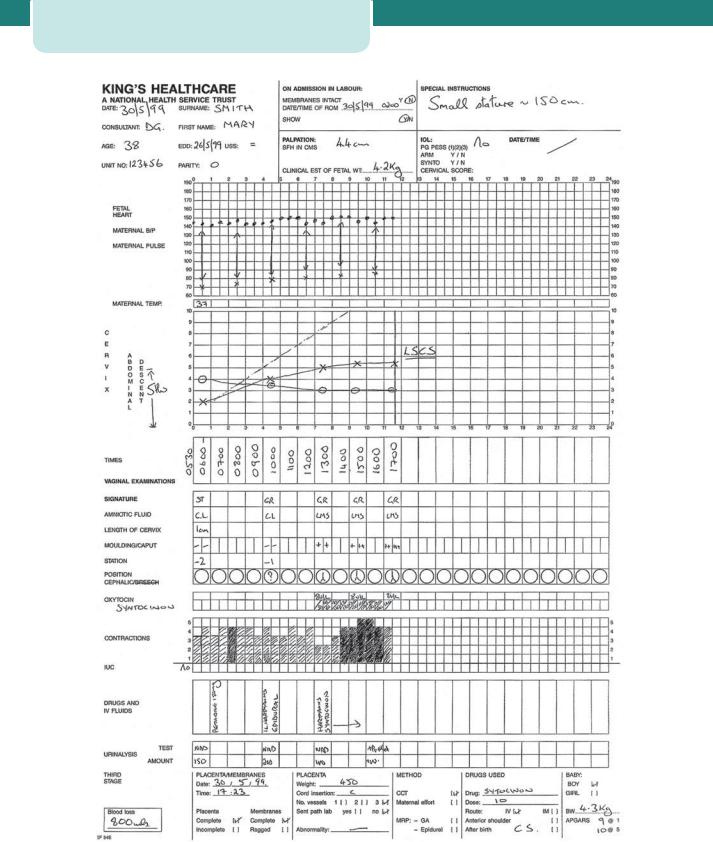

The partogram

The introduction of a graphic record of labour in the form of a partogram has been an important development. This record allows an instant visual assessment of the rate of cervical dilatation and comparison with an expected norm, according to the parity of the woman, so that slow progress can be recognized early and appropriate actions taken to correct it where possible. Other key observations are entered on to the chart, including the frequency and strength of contractions, the descent of the head in fifths palpable, the amount and colour of the amniotic fluid draining, and basic observations of maternal well-being, such as blood pressure, pulse rate and temperature (Figure 14.19).

A line can be drawn on the partogram at the end of the latent phase demonstrating progress of 1 cm dilatation per hour. Another line (‘the action line’) can be drawn parallel and 4 hours to the right of it. If the plot of actual cervical dilatation reaches the action line, indicating slow progress, then consideration should be given to a number of different measures which aim to improve progress (see below). Progress can also be considered slow if the cervix dilates at less than 1 cm every 2 hours.

Management of normal labour |

199 |

Management during first stage

Key management principles of first stage of

labour

•The first stage of labour is timed from the diagnosis of onset of labour to full dilatation of the cervix.

•Provision of continuity of care and emotional support to the mother.

•Observation of the progress of labour with timely intervention if it becomes abnormal.

•Monitoring of fetal well-being.

•Adequate and appropriate pain relief consistent with the woman’s wishes.

•Adequate hydration to prevent ketosis.

Women who are in the latent phase of labour should be encouraged to mobilize and should be managed away from the labour suite where possible. Indeed, they may well go home, to return later when the contractions are stronger or more frequent. Encouragement and reassurance are extremely important. Intervention during this phase is best avoided unless there are identified risk factors. Simple analgesics are preferred over nitrous oxide and epidurals. There is no reason to restrict eating and drinking, although lighter foods and clear fluids may be better tolerated. Vaginal examinations are usually performed every 4 hours to determine when the active phase has been reached (approximately 4 cm dilatation and full effacement). Thereafter, the timing of examinations should be decided by the midwife. Fourhourly is standard practice, however, this frequency may be increased if the midwife thinks that progress is unusually slow or fast. The lower limit of normal progress is 1 cm dilatation every 2 hours once the active phase has been reached. Descent of the presenting part through the pelvis is another crucial component of progress and should be recorded at each vaginal examination. Full dilatation may be reached, but if descent is inadequate, vaginal delivery will not occur.

During the first stage, the membranes may be intact, may have ruptured spontaneously or may have been ruptured artificially. Generally speaking, if the membranes are intact, it is not necessary to rupture them if the progress of labour is satisfactory.

Maternal and fetal observations are carried out as described previously, and recorded on the partogram. Women should receive one-to-one care (i.e. from