Encyclopedia of SociologyVol._3

.pdf

LAW AND SOCIETY

style, become a way of life. But in terms of a method or process for decision making—for determining correct rules, facts, or results—the law provides only a wide and conflicting variety of stylized rationalizations from which courts pick and choose. Social and political judgments about the substance, parties, and context of a case guide such choices, even when they are not the explicit or conscious basis of decision. (Kairys 1982, p. 3)

Not only do critical legal scholars reject the notion of legal reasoning, they also reject other idealized components constituting a ‘‘legal system,’’ in particular, that law is a body of doctrine, that the doctrine reflects a coherent view of relations between persons and the nature of society, and that social behavior reflects norms generated by the legal system (Trubek 1984, p. 577).

The general conclusion CLS writers draw from ‘‘unmasking’’ the legal system, ‘‘trashing’’ mainstream jurisprudence, and ‘‘deconstructing’’ legal scholarship (Barkan 1987) is that ‘‘law is simply politics by other means’’ (Kairys 1982, p. 17). Such a conclusion, on its face, does not hold out any promise for developing a new, let alone heuristic, approach to a theory of law and society. On the contrary, its antipositivism combined with its search for a transformative political agenda has prompted CLS writers to view with increasing skepticism the sociology of law and research into the relationship between law and society (Trubek and Esser 1989).

Autopoietic Law. Similar in some respects to Watson’s theory of legal autonomy, but fundamentally different from the theory of the CLS movement, autopoietic law claims to be a challenging new theory of law and society (Teubner 1988a). For the past few years several continental social theorists, who are also legal scholars, have enthusiastically developed and propagated the theory of autopoietic law. A complex cluster of ideas, this theory is derived from the work of two biologists, Maturana and Varela (Varela 1979; Maturana and Varela 1980).

In the course of their biological research, Maturana and Varela arrived at some methodological realizations that led them to generalize about the nature of living systems. Maturana coined the term autopoiesis to capture this new ‘‘scientific epistemology’’ (Maturana and Varela 1980, p. xvii).

‘‘This was a word without a history, a word that could directly mean what takes place in the dynamics of the autonomy proper to living systems.’’ Conceptualizing living systems as machines, Maturana and Varela present the following rather complex and abstract definition:

Autopoietic machines are homeostatic machines. Their peculiarity, however, does not lie in this but in the fundamental variable which they maintain constant . . . an autopoietic machine continuously generates and specifies its own organization through its operation

as a system of production of its own components, and does this in an endless turnover of components under conditions of continuous perturbations and compensation of perturbations. (Maturana and Varela 1980, pp. 78–79)

Another definition of autopoiesis is presented by Zeleny, one of the early advocates of this new theory:

An autopoietic system is a distinguishable complex of component-producing processes and their resulting components, bounded as an autonomous unity within its environment, and characterized by a particular kind of relation among its components, and component-produc- ing processes: the components, through their interaction, recursively generate, maintain, and recover the same complex of processes which produced them. (Zeleny 1980, p. 4)

Clearly, these definitions and postulates are rather obscure and high-level generalizations that, from a general systems theory perspective (Bertalanffy 1968), are questionable. Especially suspect is the assertion that autopoietic systems do not have inputs and outputs. The authors introduce further complexity by postulating secondand third-order autopoietic systems, which occur when autopoietic systems interact with one another and, in turn, generate a new autopoeitic system (Maturana and Varela 1980, pp. 107–111). Toward the end of their provocative monograph, Maturana and Varela raise the question of whether the dynamics of human societies are determined by the autopoiesis of its components. Failing to agree on the answer to this question, the authors postpone further discussion (Maturana and Varela 1980, p. 118). Zeleny, however, hastens to answer this question

1557

LAW AND SOCIETY

and introduces the notion of ‘‘social autopoiesis’’ to convey that human societies are autopoietic (Zeleny 1980, p. 3).

Luhmann, an outstanding German theorist and jurist, has also gravitated to the theory of autopoiesis. According to Luhmann, ‘‘social systems can be regarded as special kinds of autopoietic systems’’ (1988b, p. 15). Influenced in part by Parsons and general systems theory, Luhmann applied some systems concepts in analyzing social structures (1982). In the conclusion to the second edition of his book A Sociological Theory of Law

(1985), Luhmann briefly refers to new developments in general systems theory that warrant the application of autopoiesis to the legal system. Instead of maintaining the dichotomy between closed and open systems theory, articulated by Bertalanffy, Boulding, and Rapoport (Buckley 1968), Luhmann seeks to integrate the open and closed system perspectives. In the process he conceptualizes the legal system as self-referential, self-reproducing, ‘‘normatively closed,’’ and ‘‘cognitively open’’—a theme he has pursued in a number of essays (1985, 1986, 1988c).

This formulation is, to say the least, ambiguous. Given normative closure, how does the learning of the system’s environmental changes, expectations, or demands get transmitted to the legal system? Further complicating the problem is Luhmann’s theory of a functionally differentiated modern society in which all subsystems—includ- ing the legal system—tend to be differentiated as self-referential systems, thereby reaching high levels of autonomy (Luhmann 1982). Although Luhmann has explicitly addressed the issue of integrating the closed and open system perspectives of general systems theory, it is by no means evident from his many publications how this is achieved.

Another prominent contributor to autopoietic law is the jurist and sociologist of law Gunther Teubner. In numerous publications, Teubner discusses the theory of autopoiesis and its implications for reflexive law, legal autonomy, and evolutionary theory (Teubner 1983a, 1983b, 1988a, 1988b). One essay, ‘‘Evolution of Autopoietic Law’’ (1988a), raises two general issues: the pre-requi- sites of autopoietic closure of a legal system, and legal evolution after a legal system achieves autopoietic

closure. With respect to the first issue, Teubner applies the concept of hypercycle, which he has borrowed from others but which he does not explicitly define. Another of his essays (Teubner 1988b) reveals how Teubner is using this concept. For Teubner, all self-referential systems involve, by definition, ‘‘circularity’’ or ‘‘recursivity’’ (1988b, p. 57). Legal systems are preeminently self-refer- ential in the course of producing legal acts or legal decisions. However, if they are to achieve autopoietic autonomy their cyclically constituted system components must become interlinked in a ‘‘hypercycle,’’ ‘‘i.e., the additional cyclical linkage of cyclically constituted units’’ (Teubner 1988b, p. 55). The legal system components—as conceptualized by Teubner, ‘‘element, structure, process, identity boundary, environment, performance, function’’ (1988b, p. 55)—are general terms not readily susceptible to the construction of legal indicators.

The second question Teubner addresses, legal evolution after a legal system has attained autopoietic closure, poses a similar problem. The universal evolutionary functions of variation, selection, and retention manifest themselves in the form of legal mechanisms.

In the legal system, normative structures take over variation, institutional structures

(especially procedures) take over selection and doctrinal structures take over retention. (Teubner 1988a, p. 228)

Since Teubner subscribes to Luhmann’s theory of a functionally differentiated social system, with each subsystem undergoing autopoietic development, he confronts the problem of intersubsystem relations as regards evolution. This leads him to introduce the intriguing concept of co-evolution.

The environmental reference in evolution however is produced not in the direct, causal production of legal developments, but in processes of co-evolution. The thesis is as follows: In co-evolutionary processes it is not only the autopoiesis of the legal system which has a selective effect on the development of its own structures; the autopoiesis of other subsystems and that of society also affects—in any case in a much more mediatory and indirect way—the selection of legal changes. (Teubner 1988a, pp. 235–236)

1558

LAW AND SOCIETY

Given the postulate of ‘‘autopoietic closure,’’ it is not clear by what mechanisms nonlegal subsystems of a society affect the evolution of the legal system and how they ‘‘co-evolve.’’ Once again, we confront the unsolved problem in the theory of autopoiesis of integrating the closed and open systems perspectives. Nevertheless, Teubner, with the help of the concept of co-evolution, has drawn our attention to a critical problem even if one remains skeptical of his proposition that ‘‘the historical relationship of ‘law and society’ must, in my view, be defined as a co-evolution of structurally coupled autopoietic systems’’ (Teubner 1988a, p. 218).

At least three additional questions about autopoietic law can be raised. Luhmann’s theory of a functionally differentiated society in which all subsystems are autopoietic raises anew Durkheim’s problem of social integration. The centrifugal forces in such a society would very likely threaten its viability. Such a societal theory implies a highly decentralized social system with a weak state and a passive legal system. Does Luhmann really think any modern society approximates his model of a functionally differentiated society?

A related problem is the implicit ethnocentrism of social scientists writing against the background of highly developed Western societies where law enjoys a substantial level of functional autonomy, which, however, is by no means equivalent to autopoietic closure. In developing societies and in socialist countries, many of which are developing societies as well, this is hardly the case. In these types of societies legal systems tend to be subordinated to political, economic, or military institutions. In other words, the legal systems are decidedly allopoietic. To characterize the subsystems of such societies as autopoietic is to distort social reality.

A third problem with the theory of autopoietic law is its reliance on the ‘‘positivity’’ of law. This fails to consider a secular legal trend of great import for the future of humankind, namely, the faltering efforts—initiated by Grotius in the seventeenth century—to develop a body of international law. By what mechanisms can autopoietic legal systems incorporate international legal norms? Because of the focus on ‘‘positivized’’ law untainted by political, religious, and other institutional values, autopoietic legal systems would have a

difficult time accommodating themselves to the growing corpus of international law.

Stimulating as is the development of the theory of legal autopoiesis, it does not appear to fulfill the requirements for a fruitful theory of law and society (Blankenburg 1983). In its present formulation, autopoietic law is a provocative metatheory. If any of its adherents succeed in deriving empirical propositions from this metatheory (Blankenburg 1983), subject them to an empirical test, and confirm them, they will be instrumental in bringing about a paradigm shift in the sociology of law.

The classical and contemporary theories of law and society, reviewed above, all fall short in providing precise and operational guidelines for uncovering the linkages over time between legal and nonlegal institutions in different societies. Thus, the search for a scientific macro sociolegal theory will continue. To further the search for such a theory, a social-structural model will now be outlined.

A SOCIAL-STRUCTURAL MODEL

A social-structural model begins with a theoretical amalgam of concepts from systems theory with Parsons’ four structural components of social systems: values, norms, roles, and collectivities (Parsons 1961, pp. 41–44; Evan 1975, pp. 387–388). Any subsystem or institution of a societal system, whether it be a legal system, a family system, an economic system, a religious system, or any other system, can be decomposed into four structural elements: values, norms, roles, and organizations. The first two elements relate to a cultural or normative level of analysis and the last two to a social-structural level of analysis. Interactions between two or more subsystems of a society are mediated by cultural as well as by social-structural elements. As Parsons has observed, law is a generalized mechanism for regulating behavior in the several subsystems of a society (Parsons 1962, p. 57). At the normative level of analysis, law entails a ‘‘double institutionalization’’ of the values and norms embedded in other subsystems of a society (Bohannan 1968). In performing this reinforcement function, law develops ‘‘cultural linkages’’ with other subsystems, thus contributing to the degree of normative integration that exists in a society. As disputes are adjudicated and new legal norms are enacted, a

1559

LAW AND SOCIETY

value from one or more of the nonlegal subsystems is tapped. These values provide an implicit or explicit justification for legal decision making.

Parsons’s constituents of social structure (values, norms, roles, and organizations) are nested elements, as in a Chinese box, with values incorporated in norms, both of these elements contained in roles, and all three elements constituting organizations. When values, norms, roles, and organizations are aggregated we have a new formulation, different from Parsons’s AGIL paradigm, of the sociological concept of an institution. An institution of a society is composed of a configuration of values, norms, roles, and organizations. This definition is applicable to all social institutions, whether economic, political, religious, familial, educational, scientific, technological, or legal. In turn, the social structure of a society is a composite of these and other institutions.

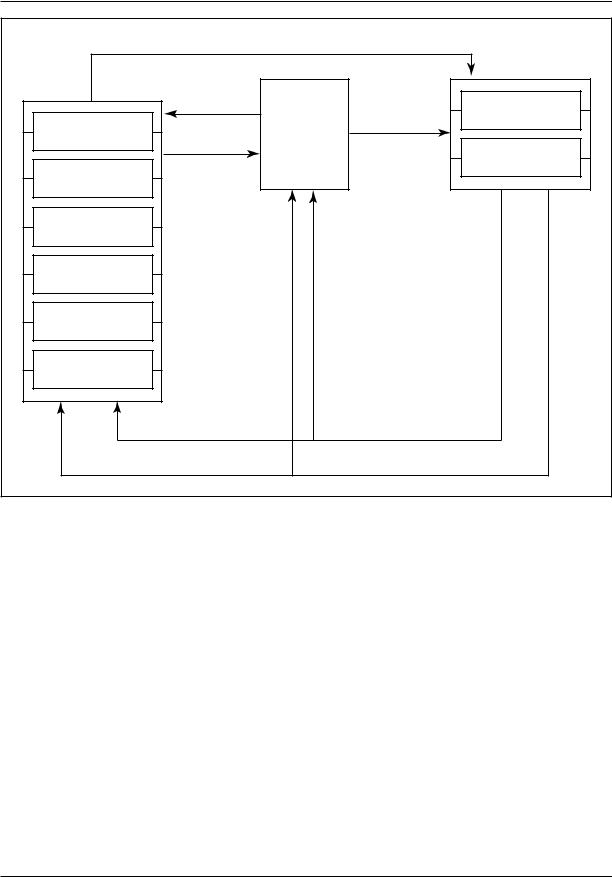

Of fundamental importance to the field of the sociology of law is the question of how the legal institution is related to each of the nonlegal institutions. A preliminary answer to this question will be set forth in a model diagramming eight types of interactions or linkages between legal and nonlegal institutions (see Figure 1).

On the left-hand side of the diagram are a set of six nonlegal institutions, each of which is composed of values, norms, roles, and organizations. If the norms comprising the nonlegal institutions are sufficiently institutionalized, they can have a direct regulatory impact on legal personnel as well on the citizenry (interaction 4, ‘‘Single institutionalization’’). On the other hand, according to Bohannan (1968), if the norms of the nonlegal institutions are not sufficiently strong to regulate the behavior of the citizenry, a process of ‘‘double institutionalization’’ (interaction 1) occurs whereby the legal system converts nonlegal institutional norms into legal norms. This effect can be seen in the rise in the Colonial period of ‘‘blue laws,’’ which were needed to give legal reinforcement to the religious norms that held the Sabbath to be sacred (Evan 1980, pp. 517–518, 530–532). In addition, the legal system can introduce a norm that is not a component of any of the nonlegal institutions. In other words, the legal system can introduce an innovative norm (interaction 2) that does not have a counterpart in any of the nonlegal institutions (Bohannan 1968). An example of such

an innovation is ‘‘no-fault’’ divorce (Weitzman 1985; Jacob 1988).

The legal system’s regulatory impact (interaction 3) may succeed or fail with legal personnel, with the citizenry, or with both. Depending on whether legal personnel faithfully implement the law, and the citizenry faithfully complies with the law, the effect on the legal system can be reinforcing (interaction 7) or subversive (interaction 5), and the effect on nonlegal institutions can be stabilizing (interaction 9) or destabilizing (interaction 6).

In systems-theoretic terms, the values of a society may be viewed as goal parameters in comparison with which the performance of a legal system may be objectively assessed. The inability of a legal system to develop ‘‘feedback loops’’ and ‘‘closed loop systems’’ to monitor and assess the efficacy of its outputs makes the legal system vulnerable to various types of failures. Instead of generating ‘‘negative feedback,’’ that is, self-cor- rective measures, when legal personnel or rank- and-file citizens fail to comply with the law, the system generates detrimental ‘‘positive feedback’’ (Laszlo, Levine, and Milsum 1974).

CONCLUSION

What are some implications of this social-structur- al model? In the first place, the legal system is not viewed as only an immanently developing set of legal rules, principles, or doctrines insulated from other subsystems of society, as expressed by Watson and to some extent by Luhmann and Teubner. Second, the personnel of the legal system, whether judges, lawyers, prosecutors, or administrative agency officials, activate legal rules, principles, or doctrines in the course of performing their roles within the legal system. Third, formally organized collectivities, be they courts, legislatures, law-en- forcement organizations, or administrative agencies, perform the various functions of a legal system. Fourth, in performing these functions, the formally organized collectivities comprising a legal system interact with individuals and organizations representing interests embedded in the nonlegal subsystems of a society. In other words, each of the society’s institutions or subsystems— legal and nonlegal—has the same structural elements: values, norms, roles, and organizations.

1560

LAW AND SOCIETY

|

|

(4) "Single Institutionalization" |

|

||

Nonlegal |

System |

(2) |

|

|

Behavior of |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Innovation |

|

(3) |

Legal Personnel |

Economic |

Legal System |

|

|||

|

Regulatory |

|

|||

|

|

(1) |

|

Behavior of |

|

|

|

|

Impact |

||

|

|

"Double Insti- |

|

||

|

|

|

|

Citizenry |

|

Political |

tutionalization" |

|

|

|

|

Familial |

|

|

|

|

|

Religious |

|

|

|

|

|

Educational |

|

|

|

|

|

Scientific/ |

|

|

|

|

|

Technological |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(6) Destabilizing Function |

|

(5) Subversive Function |

|

|

|

(8) Stabilizing Function |

|

(7) Reinforcement Function |

|

Figure 1

NOTE: A Social-Structural Model of the Interactions of Legal and Nonlegal Institutions

Interinstitutional interactions involve an effort at coupling these structural elements across institutional boundaries. A major challenge to the sociologists of law is to discover the diverse coupling or linkages—cultural and social-structural—be- tween the legal system and the nonlegal systems in terms of the four constituent structural elements. Another challenge is to ascertain the impact of these linkages on the behavior of legal personnel and on the behavior of the citizenry, on the one hand, and to measure the impact of ‘‘double institutionalization’’ on societal goals, on the other.

A serendipitous outcome of this model is that it suggests a definition of law and society or the sociology of law, that is, that the sociology of law deals primarily with at least eight interactions or

linkages identified in Figure 1. Whether researchers accept this definition will be determined by its heuristic value, namely, whether it generates empirical research concerning the eight linkages.

(SEE ALSO: Law and Legal Systems; Social Control; Sociology

of Law)

REFERENCES

Abraham, David 1994 ‘‘Persistent Facts and Compelling Norms: Liberal Capitalism, Democratic Socialism, and the Law.’’ Law and Society Review 28:939–946

Barkan, Steven M. 1987 ‘‘Deconstructing Legal Research: A Law Librarian’s Commentary on Critical Legal Studies.’’ Law, Library Journal 79:617–637.

1561

LAW AND SOCIETY

Barnett, Larry D. 1993. Legal Construct, Social Concept: a Macrosociological Perspective On Law. Hawthorne, N.Y.: Aldine De Gruyter.

Baxi, U. 1974 ‘‘Comment—Durkheim and Legal Evolution: Some Problems of Disproof.’’ Law and Society Review 8:645–651.

Bendix, Reinhard 1960 Max Weber: An Intellectual Portrait. New York: Doubleday.

Berman, Harold J. 1963 Justice in the U.S.S.R: An Interpretation of the Soviet Law. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Bertalanffy, Ludwig von 1968 General System Theory. New York: G. Braziller.

Blankenburg, Erhard 1983 ‘‘The Poverty of Evolutionism: A Critique of Teubner’s Case for ‘Reflexive Law.’’’

Law and Society Review 18:273–289.

Bohannan, Paul 1968 ‘‘Law and Legal Institutions.’’ In David L. Sills, ed., International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. New York: Macmillan and Free Press.

Buckley, Walter (ed.) 1968 Modern Systems Research for the Behavioral Scientist. Chicago: Aldine.

Burman, Sandra, and Barbara E. Harrell-Bond (eds.) 1979 The Imposition of Law. New York: Academic Press.

Chambliss, William J., and S. Zatz Marjorie 1993 Making Law: The State, the Law, and Structural Contradictions. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Collins, Randall 1980 ‘‘Weber’s Last Theory of Capitalism: A Systemization’’ American Sociological Review

45:925–942.

Cooney, Mark 1995 ‘‘Legal Sociology and the New Institutionalism.’’ Studies in Law Politics, and Society

15:85–101.

Cotterell, Roger 1997 Law’s Community: Legal Theory In Sociological Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

——— 1988 ‘‘Why Must Legal Ideas Be Interpreted Sociologically?’’ Journal of Law and Society 25:171–192.

David, Rene, and John E. C. Brierley 1968 Major Legal Systems in the World Today. London: Free Press and Collier-Macmillan.

Durkheim, Emile 1933 The Division of Labor in Society. New York: Free Press.

Eisenstadt, S. N., and M. Curelaru 1977 ‘‘Macro-Sociolo- gy: Theory, Analysis and Comparative Studies.’’ Current Sociology 25:1–112.

Evan, William M. 1965 ‘‘Toward A Sociological Almanac of Legal Systems.’’ International Social Science Journal 17:335–338.

———1968 ‘‘A Data Archive of Legal Systems: A CrossNational Analysis of Sample Data.’’ European Journal of Sociology 9:113–125.

———1975 ‘‘The International Sociological Association and the Internationalization of Sociology.’’ International Social Science Journal 27:385–393.

———1980 The Sociology of Law. New York: Free Press.

———1990 Social Structure and Law: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

Glendon, Mary Ann 1975 ‘‘Power and Authority in the Family: New Legal Patterns as Reflections of Changing Ideologies.’’ American Journal of Comparative Law 23:1–33.

Habermans, Jurgen, and William Regh 1996. Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hazard, John N. 1977 Soviet Legal System: Fundamental Principles and Historical Commentary, 3rd ed. Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Oceana Press.

Jacob, Herbert 1988 Silent Revolution: The Transformation of Divorce Law in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kairys, David (ed.) 1982 The Politics of Law. New York:

Pantheon.

Laszlo, C. A., M. D. Levine, and J. H. Milsum 1974 ‘‘A General Systems Framework for Social Systems.’’

Behavioral Science 19:79–92.

Lidz, Victor 1979 ‘‘The Law as Index, Phenomenon, and Element: Conceptual Steps Towards a General Sociology of Law.’’ Sociological Inquiry 49:5–25.

Luhmann, Niklas 1982 The Differentiation of Society. New York: Columbia University Press.

———1985 A Sociological Theory of Law. trans. Elizabeth King and Martin Albrow. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

———1986 ‘‘The Self-Reproduction of Law and Its Limits.’’ In Gunther Teubner, ed., Dilemmas of Law in the Welfare State. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

———1988a ‘‘The Sociological, Observation of the Theory and Practice of Law.’’ In Alberto Febrajo, ed.,

European Yearbook in the Sociology of Law. Milan: Giuffre Publisher.

———1988b ‘‘The Unity of Legal Systems.’’ In Gunther Teubner, ed., Autopoietic Law: A New Approach to Law and Society. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

———1988c ‘‘Closure and Openness: On Reality in the World of Law.’’ In Gunther Teubner, ed., Autopoietic Law: A New Approach to Law and Society. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

1562

LEADERSHIP

McIntyre, Lisa J. 1994 Law in the Sociological Enterprise: a Reconstruction. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

Maturana, Humberto R., and Francisco J. Varela 1980

Autopoiesis and Cognition. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: D. Reidel Publishing.

Merryman, John Henry, David S. Clark, and Lawrence M. Friedman 1979 Law and Social Change in Mediterranean Europe and Latin America. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford Law School.

Parsons, Talcott 1961 ‘‘An Outline of the Social System.’’ In Talcott Parsons, Edward Shils, Kasper D. Naegele, and Jesse R. Pitts, eds., Theories of Society. New York: Free Press.

———1962 ‘‘The Law and Social Control.’’ In William M. Evan, ed., Law and Sociology. New York: Free Press.

———1978 ‘‘Law as an Intellectual Stepchild.’’ In Harry M. Johnson, ed., Social System and Legal Process. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Rheinstein, Max (ed.) 1954 Max Weber on Law in Economy and Society. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Schwartz, R. D. 1974 ‘‘Legal Evolution and the Durkheim Hypothesis: A Reply to Professor Baxi.’’ Law and Society Review 8:653–668.

———, and J. C. Miller 1964 ‘‘Legal Evolution and Social Complexity.’’ American Journal of Sociology

70:159–169.

Sheleff, L. S. 1975 ‘‘From Restitutive Law to Repressive Law: Durkheim’s The Division of Labor in Society Revisited.’’ European Journal of Sociology 16:16–45.

Tamanaha, Brian Z. 1996 ‘‘The Internal/External Distinction and the Notion of a ‘‘Practice’’ in Legal Theory and Sociolegal Studies.’’ Law and Society Review 30:163–204.

——— 1999 Realistic Socio-Legal Theory: Pragmatism and A Social Theory of Law. New York: Oxford University Press.

Teubner, Gunther 1983a ‘‘Substantive and Reflexive Elements in Modern Law.’’ Law and Society Review 17:239–285.

———1983b ‘‘Autopoiesis in Law and Society: A Rejoinder to Blankenburg.’’ Law and Society Review 18:291–301.

———1988a Autopoietic Law: A New Approach to Law and Society. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

———1988b ‘‘Hypercycle in Law and Organization: The Relationship Between Self-Observation, Self-Con- stitution, and Autopoiesis.’’ In Alberto Febrajo, ed.,

European Yearbook in the Sociology of Law. Milan: Giuffre Publisher.

——— 1997 ‘‘The King’s Many Bodies: The SelfDeconstruction of Law’s Hierarchy.’’ Law and Society Review 31:763–787.

Travers, Max 1993 ‘‘Putting Sociology Back into the Sociology of Law.’’ Journal of Law and Society 20:438–451.

Trubek, David M. 1972 ‘‘Max Weber on Law and the Rise of Capitalism.’’ Wisconsin Law Review 730:720–753.

——— 1984 ‘‘Where the Action Is: Critical Legal Studies of Empiricism.’’ Stanford Law Review 36:575.

———, and John Esser 1989 ‘‘’Critical Empiricism’ in American Legal Studies: Paradox, Program, or Pandora’s Box?’’ Law and Social Inquiry 14:3–52.

Varela, Francisco J. 1979 The Principle of Autonomy. New

York: North-Holland.

Watson, Alan 1974 Legal Transplants: An Approach to Comparative Law. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

———1978 ‘‘Comparative Law and Legal Change.’’

Cambridge Law Journal 37:313–336.

———1981 The Making of the Civil Law. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

———1983 ‘‘Legal Change, Sources of Law, and Legal Culture.’’ University of Pennsylvania Law Review

131:1,121–1,157.

———1985 The Evolution of Law. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press.

———1987 ‘‘Legal Evolution and Legislation.’’ Brigham Young University Law Review 1987:353–379.

Weber, Max 1950 General Economic History. New York:

Free Press.

Weitzman, Lenore J. 1985 The Divorce Revolution: The Unexpected Social and Economic Consequences for Women and Children in America. New York: Free Press.

Wigmore, John Henry 1928 A Panorama of the World’s Legal Systems. 3 vols. St. Paul, Minn.: West Publishing.

Zeleny, Milan 1980 Autopoiesis, Dissipative Structures, and Spontaneous Social Orders. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

WILLIAM M. EVAN

LAW ENFORCEMENT

See Criminology; Penology; Police.

LEADERSHIP

The concept of leadership has been the focus of research and discussion of scholars in a variety of

1563

LEADERSHIP

disciplines. Literary authors and philosophers provided the initial descriptions and guidance for leaders of their time. With the evolution of social sciences, scholars of political science, anthropology, sociology, psychology, and business have all explored the nature of leaders and the process of leadership. Although each of these various approaches did add a different perspective through the decades, there seem to be some who perceive a merging of disciplines in understanding leadership as we approach the close of the twentieth century. However, there are others who still maintain that leaders in different settings are fundamentally different.

As leadership is a vast field of research, only the most prevalent and unique approaches will be acknowledged in the following sections. Readers can find a more thorough review of leadership research and theories in texts such as Bass (1990), Chemers (1997), Chemers and Ayman (1993), and Dansereau and Yammarino (1998).

HISTORICAL REVIEW

The definition of leadership has varied across time and cultures. In ancient times, the focus was on kings and rulers, who received guidance from philosophers. In many civilizations around the world, authors have written essays on good and bad leadership. For example, Confucius and Mencius wrote essays on leaders’ proper behavior during the end of the fourth century and the beginning of the fifth century B.C. in China. Aristotle’s book, The Politics, describes the characteristics of the kings and kingship in ancient Greece (fourth century B.C.). In eleventh-century Iran, Unsuru’l-Ma’ali wrote Qabus-Nameh and Nezam Mulk Tussi wrote Siyassat Nameh, advising the kings of the time in effective governance. Machiavelli wrote The Prince, in Florence, Italy, during the sixteenth century, guiding European rulers in politics. Ibn-e-khaldun from Tunisia provided his observations and guidance to the ruling groups of North Africa in his famous book Muqiddimah in the fourteenth century.

From the end of the eighteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century, during the evolution of industrialization, the concept of ‘‘leader’’ also came to include leaders of industry. Only a hundred and fifty years ago the first chief executive officer (CEO) appeared (Smoler 1999). Smoler

stated that the increased volume of economic activity required the increased efficiency and administrative coordination that gave rise to this kind of leadership. The twentieth century saw steep growth in the numbers of CEOs and of top executive management positions.

At the close of the twentieth century there is a debate on differentiating between leaders and managers, and between leadership and management (Kotter 1988). The saying that some leaders and managers both lead and manage, but most leaders do not manage and most managers do not lead, may make this distinction. A popular phrase that clarifies the relation between leader and managers is, ‘‘Good managers do things right and good leaders do the right thing.’’

At the beginning of the twentieth century, two schools of thought on leadership evolved (Ayman 1993; Bass 1990). In Britain, Thomas Carlyle (1907) presented the ‘‘great-man theory,’’ and in Germany, Karl Marx (1906) explained leadership from a zeitgeist approach (i.e., as being in the spirit of the time). The great-man approach focuses on the unique characteristics of the individual as the basis for being a leader. In this approach there is a strong belief that some people have leadership qualities and some do not; thus the born-leader concept. In the zeitgeist approach, the assumption is that the situation provides the opportunity for the individual to become a leader. Thus, it is not the person but the circumstances or the waves of time that puts people in leadership positions. These two approaches have been the foundation of leadership research throughout the twentieth century.

As the end of the century is approaching, the fascination with leaders seems to be at an all-time high, based on the number of publications about and for leaders (Ayman 1997). Many of these publications are inspirational and guiding. The scholars of leadership maintain a steady effort to refine the conceptualization of leadership and enhance the methodologies used in the study of leadership.

The twentieth century was the beginning of scientific and systematic study of leadership. Many disciplines have contributed to this endeavor, such as political science, anthropology, sociology, social psychology, and, most recently, industrial and organizational psychology. Each discipline has explored this phenomenon uniquely, guided by its

1564

LEADERSHIP

own perspective and orientation. The psychologists’ focus was initially influenced by the ‘‘greatman theory,’’ whereas the sociologists and social psychologists were more interested in the situational perspective. As the investigations proceeded and the disciplines evolved, the interplay of these approaches and the complexity of leadership became apparent. The following sections will briefly review various approaches: the trait and behavior approaches, which evolved from the greatman theory; the situational approach, which evolved from the zeitgeist approach; and, finally, the contingency approach, which combined the two approaches. At the end of this article, some challenges facing leadership practice and research are delineated.

TRAIT APPROACH

The initial work on leadership was influenced by the great-man theory, which focuses on the characteristics of individuals in leadership situations. The primary focus of this approach is to compare the characteristics of those who are leaders and those who are not. The majority of trait research began in the early part of the twentieth century and declined somewhat in the late 1940s. In a majority of these studies, there seemed to be a search for one trait that best differentiated leaders from nonleaders. Stogdill (1948) reviewed studies in various settings and identified a list of traits that were most commonly studied to identify leaders. The traits that differentiated leaders from nonleaders included ‘‘sociability, initiative, persistence, knowing how to get things done, self-confidence, alertness to and insight into situations, cooperativeness, popularity, adaptability, verbal facility’’ (Bass 1990, p. 75). However, Stogdill (1948) concluded that research on leader’s traits is inconclusive and that, depending on the situation, one trait may be more important than another.

Early industrial psychologists interested in selection maintained their focus on the trait approach. Therefore, primary pursuit of trait approach was by practitioners who were interested in selection and succession planning of managers in work settings. Later, Lord and colleagues (1986), with the assistance of meta-analytical techniques, reanalyzed past research by Stogdill (1948) and Mann (1959) and, across studies, identified certain

characteristics more associated with leaders than with nonleaders. The result of these studies was to identify intelligence, masculinity, and dominance as strongly related to leadership, whereas adaptability, introversion/extroversion, and conservatism had a weaker relationship. The adjustment and flexibility competency has received attention in recent years. In various studies, adaptability, as operationalized by the self-monitoring scale (Snyder 1979), has also been used to predict leader emergence and effectiveness with some degree of success (Zaccaro et al. 1991; Ayman and Chemers 1991). Hogan and colleagues (1994) revived interest in the trait approach by introducing a multitrait approach to the study of leaders. The traits included in the profile are known as the ‘‘big five’’ and consist of extroversion, emotional stability, openness, intellect, and surgency. In addition to the big five, there are also other measures (e.g., Myers Briggs) that are used to identify leader’s profiles. However, results for predicting effective leaders from these traits are inconclusive. Overall, most of the trait research has focused on differentiating the characteristics of leaders from nonleaders, and on measuring leadership potential.

BEHAVIORAL APPROACH

The first known study focusing on leader behavior examined the differing effects of democratic, autocratic, and laissez-faire leadership behaviors (Lewin et al. 1939; Lippitt and White 1943). These studies were conducted with groups of Boy Scouts led by trained graduate students. The results of these studies showed that groups with democratic leaders had the best-satisfied members. Those with autocratic leaders demonstrated the highest level of task activity, but only when the leader was present. Starting in the 1950s, the interest of the U.S. scholar gravitated toward understanding the leader’s behaviors and the relationship between these behaviors and effectiveness. Three main research centers concurrently studied leader behavior in small teams at Ohio State University, led by Stogdill and his associates; at the University of Michigan, led by Likert and his colleagues; and at Harvard, led by Bales and his collaborators. Although these studies were conducted in different work settings such as the military, education, insurance companies, car manufacturing, and laboratory settings, they all found the same results.

1565

LEADERSHIP

These results led to two categories of leader behavior. One category dealt with behaviors that establish and maintain relationships, commonly referred to as considerate, people-oriented, or socio-emo- tional behaviors. The second category focused on behaviors that get the task accomplished, commonly referred to as initiating-structure, produc- tion-oriented, or task-focused behaviors. Although many measures were designed to assess the leader’s behaviors, the most prominent are three Ohio State measures: the Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire (LBDQ), the Subordinate Behavior Description, and the Leader Opinion Questionnaire (Cook et al. 1985).

The leadership behavior researchers in other countries identified two similar categories of structure and consideration, but also found some additional categories. Unlike the findings in the United States, the two behaviors in Iran were found to be intertwined, resulting in the concept of ‘‘benevolent paternalism,’’ or the ‘‘father figure’’ leader (Ayman and Chemers 1983). In India, Sinha (1984) identified ‘‘nuturant-task’’ behavior as an addition to the two main behavioral categories. In Japan, Misumi (1985) introduced a measure that had behavioral categories similar to those in the U.S. findings, but the behaviors were assessed in context. He referred to this model as maintenanceproduction (MP) behaviors.

In the 1960s and 1970s, researchers investigated the relationship between these two categories of behaviors and various indexes of effectiveness (e.g., team satisfaction, performance, turnover, and grievance) in different work settings. Fisher and Edward’s meta-analysis (1988) is among the studies that supported the overall effects of these two behaviors (cited in Bass 1990).

Since the middle of the 1980s, a paradigm shift in the study of leadership behavior emerged, which moved scholars from focusing on consideration and initiating structure behaviors, often referred to as ‘‘transactional leadership,’’ to what is referred to as ‘‘transformational leadership’’ behavior. This movement started with the work of McGregor Burns (1978) and House (1977), and was further developed by two groups of scholars, Bass and Avolio (see Bass 1985); Avolio and Bass (1988) in the United States, and Conger and Kanungo (1987) in Canada. In this new approach,

the leader provided guidance to ensure that the work was done properly and that subordinates were happy, and also was responsible for developing a relationship with employees based on mutual trust. It was proposed that transformational leadership not only changes the subordinate, but is also evolutionary for the leader and the task. A recent meta-analysis has provided a promising review of the effects of transformational leadership behavior in a variety of settings (Lowe et al. 1996). Also, it was through these approaches that the emphasis on empowerment in leadership evolved (Conger and Kanungo 1988b). Empowering, coaching, and facilitating are behaviors that were not noted extensively in leadership literature until the middle of the 1980s. During this period many inspirational and guiding documents were presented by various authors (e.g., Kouzes and Posner 1987).

Three main categories of criticism have been directed at the behavioral approaches. The first, advanced by Korman (1966) and by Kerr and colleagues (1974), argued that situational factors moderate the relationship between leader’s behavior and outcomes. In addition, Fisher and Edwards (1988) more recently reviewed the studies using LBDQ and outcome variables, and acknowledged that there is a need for studying moderators.

The second criticism is based on the fact that almost all leader behavior measures are based on perception of self or the perception of others (Ayman 1993). In the 1980s, a series of studies demonstrated that perceived behavior is contaminated with various factors that are not necessarily related to the leader’s behavior (Lord and Maher 1991). In these studies it was demonstrated that people’s memory of the behaviors that occurred can be affected by what they think of the leader (e.g., Larson 1982; Philips and Lord 1982). The implication of this criticism is critical in exploration of diversity and cross-cultural leadership, topics that will be discussed later.

The third criticism focused on the level of conceptualization and analysis. This criticism is based on the premise that leaders may treat different people differently. That is to say, is leadership a group-level phenomenon, dyadic, or is it in the eyes of the beholder? Recently, a multilevel approach has been investigated in relation to various

1566